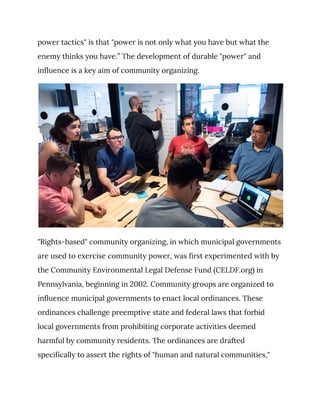

Community organizing involves people in a community coming together as an organization to act in their shared self-interest. There are four main types of community organizing: grassroots organizing, faith-based community organizing, broad-based organizing, and political campaigns. Grassroots organizing involves building community groups from scratch by developing new leadership. Faith-based community organizing uses religious congregations as a base for organizing. Broad-based organizing recruits both secular and religious institutions. Political campaigns sometimes claim to organize communities but focus only on voter turnout. The overall goal of community organizing is to empower community members and more equally distribute power throughout the community.