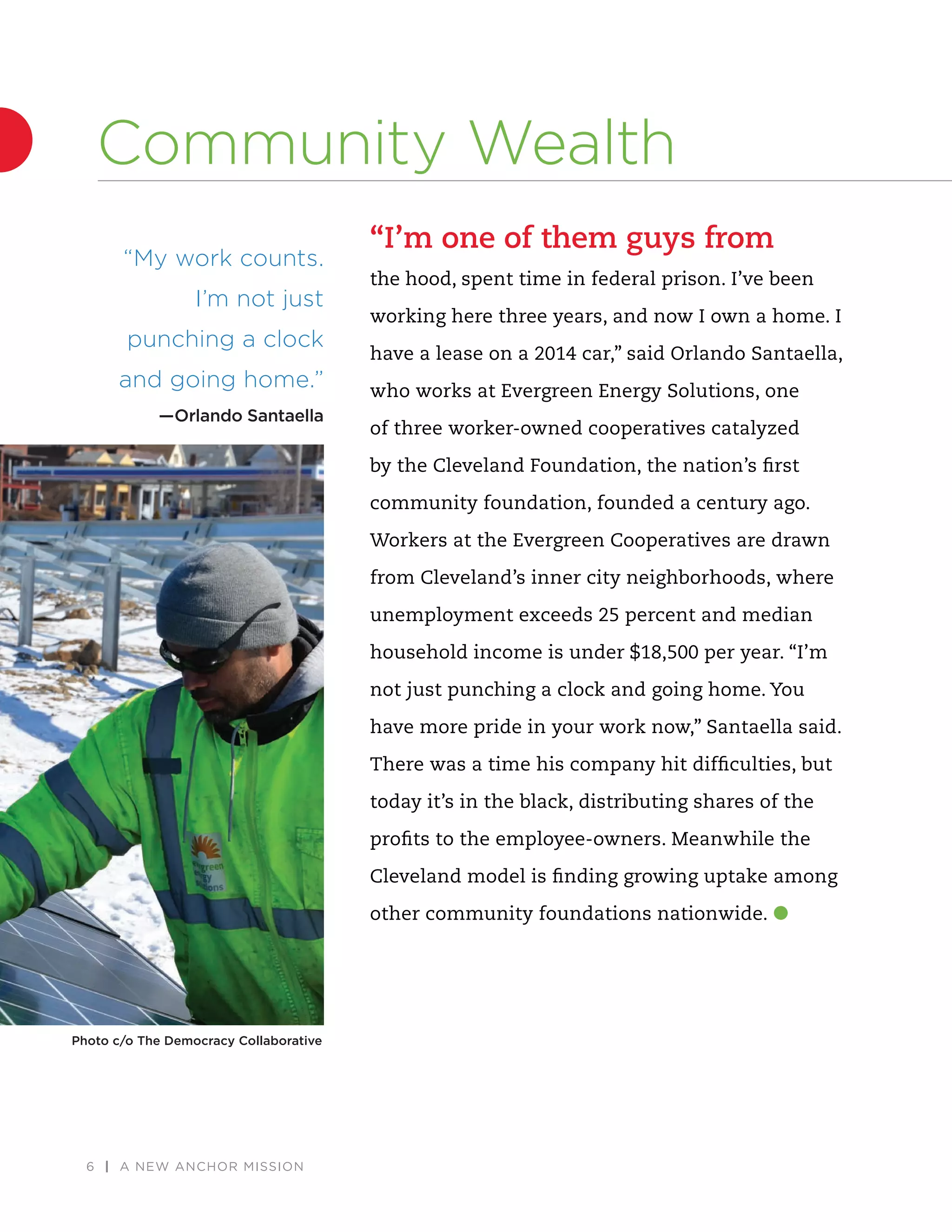

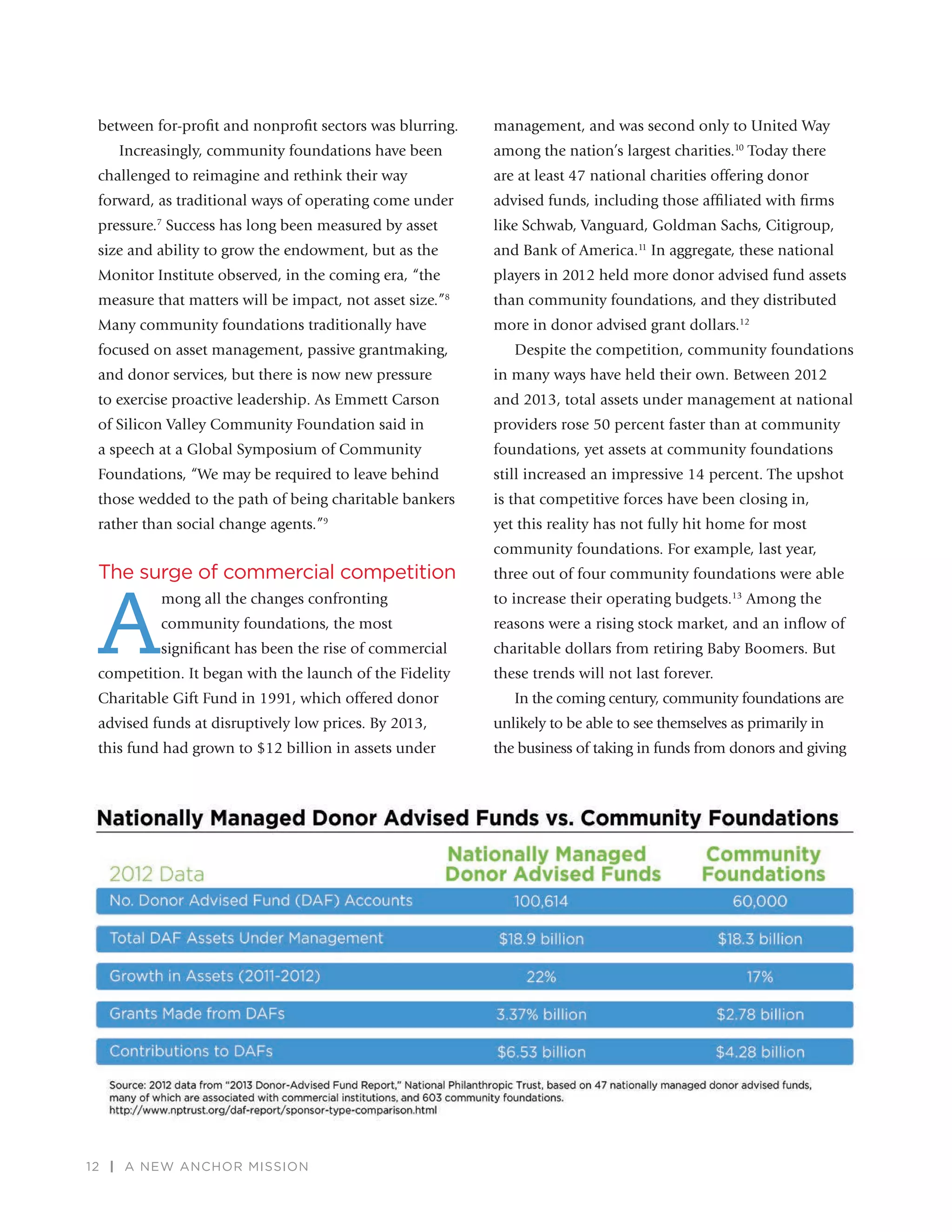

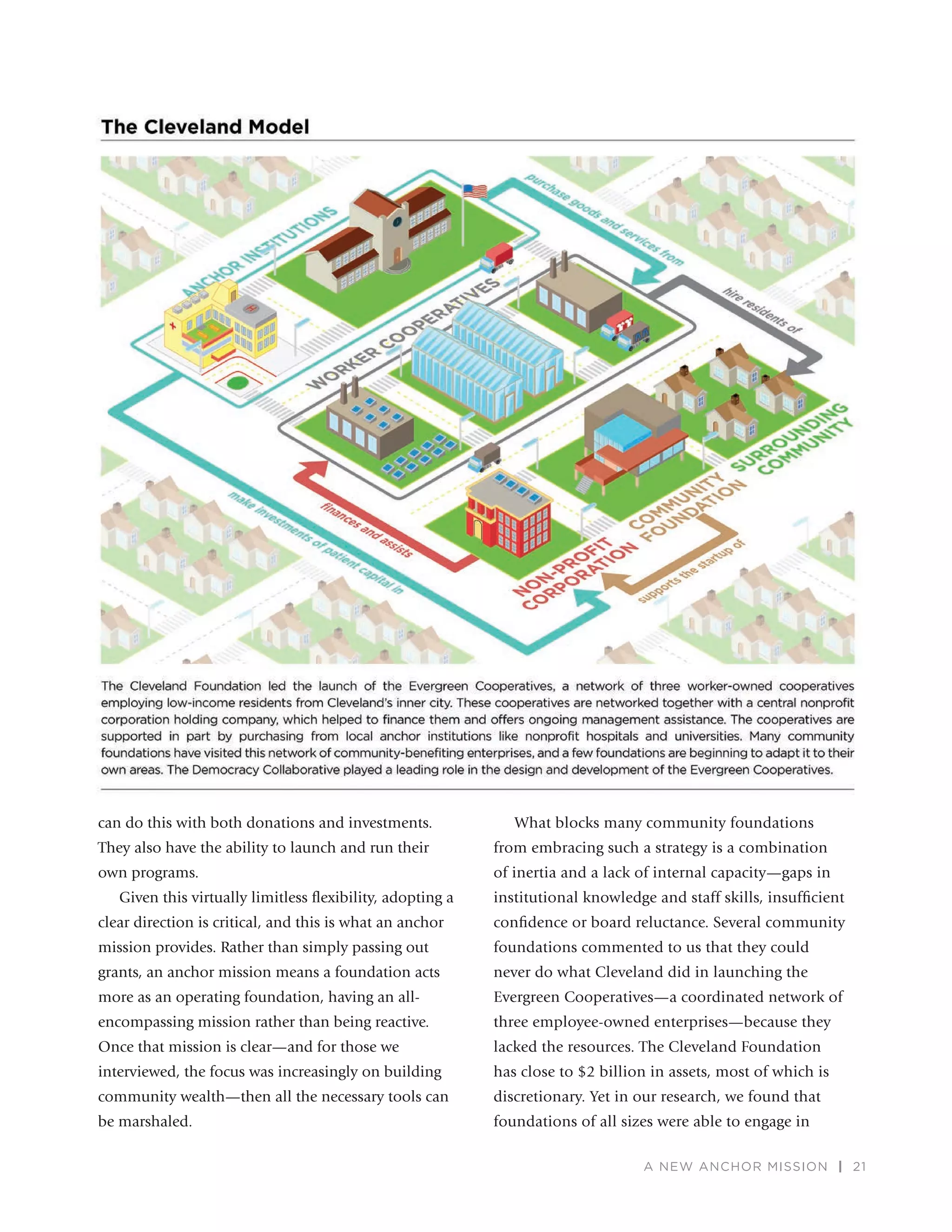

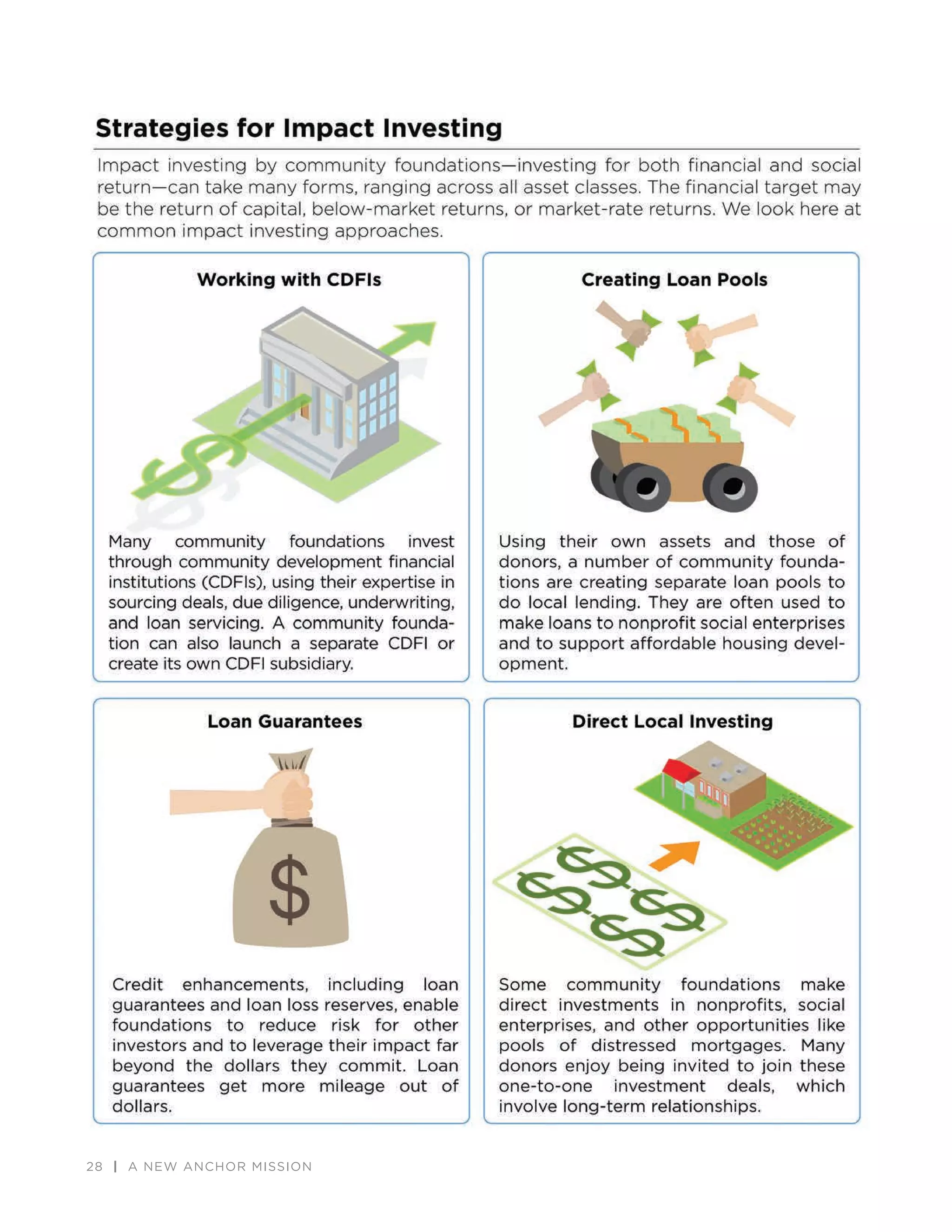

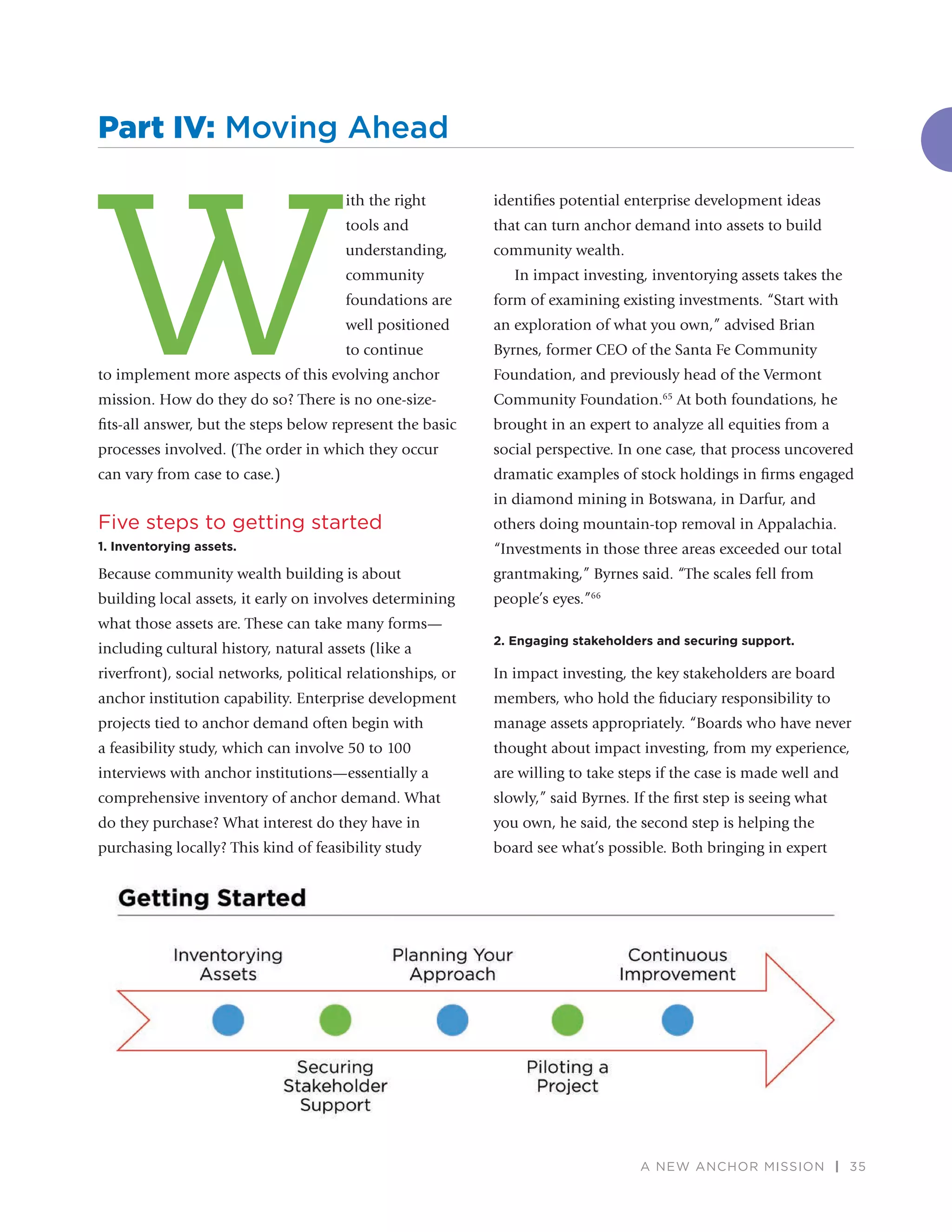

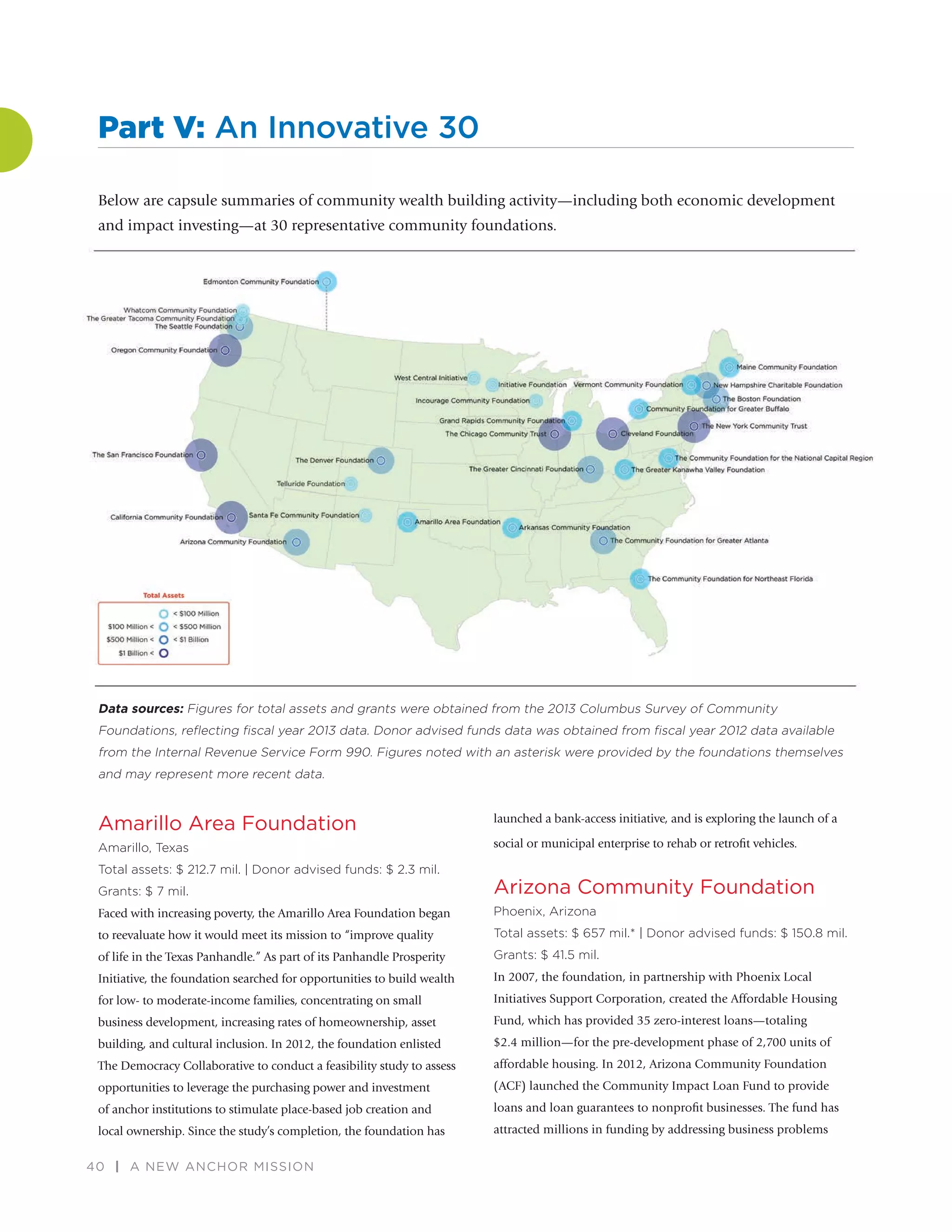

This document summarizes an emerging trend of community foundations adopting an "anchor mission" to leverage all of their resources, including financial, human, intellectual, and political assets, to build wealth in their local communities. It provides examples of 30 community foundations taking steps like impact investing and economic development to strengthen local economies. The document suggests community foundations are well-positioned as place-based institutions to serve as anchors in their communities and can deploy their over $65 billion in endowments and $5 billion in annual grants to address issues like lack of good jobs and wealth inequality. It highlights foundations in various locations that are innovating in this area through small programs or more advanced approaches.