This document provides a toolkit for new leaders in developing collaborative healthcare teams. It contains 5 modules that address key topics for building effective interprofessional teams. The first module discusses leadership concepts and styles that are important for leading teams, such as transformational leadership that focuses on relationships and empowering individuals. It also identifies qualities of effective leaders, including being able to learn and adapt to different situations. The module provides guidance for new healthcare leaders on developing strong leadership to establish collaborative teams.

![i. Past Experiences with Power20

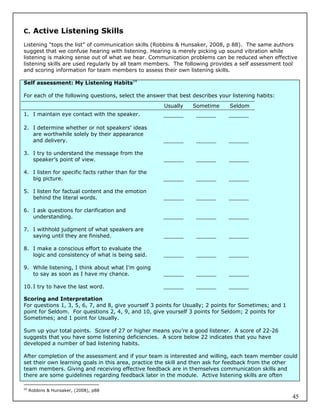

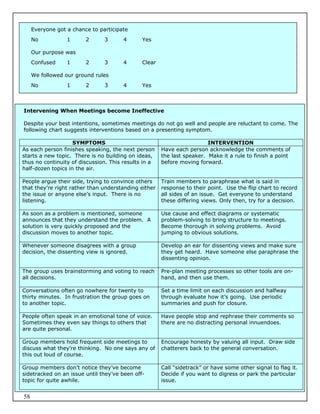

Objectives:

1. To revisit experiences with power

2. To distinguish elements that contribute to positive or negative feelings about power

3. To create an initial foundation for further discussions of the concept of power

Materials needed:

Chart paper

Felt pens

Individually write down one example of a time when you observed or experienced power being used in

a positive or productive manner. You may have observed this in person, on television, from afar, or

actually used your power in this way. After you note this experience, write down what it was about this

experience that caused you to remember it as productive and positive?

Then, write down one example of a time when you observed or experienced power being used in a

negative, disrespectful or destructive way. Again, this may have been power observed or experienced

in person, on television or from afar. Note what caused you to remember this experience as negative.

In your [small] group, share the details and reactions to both of these experiences. On one piece of

chart paper, collate the elements that comprised positive experiences. On another piece of chart paper,

collate the elements that comprised negative experiences. Each group will share its thoughts and

listings with the whole group and post. As a whole group, discuss whether the positive or negative

experiences have influenced your current views of power and why that might be.

20

McKinley, L. and Ross, H. (2008) You and Others Reflective Practice for Group Effectiveness in Human Services. Toronto:

Pearson Education.

18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/collaborativeteamstoolkitmar2009drshabon-120820202121-phpapp01/85/Collaborative-teams-toolkit-mar-2009-dr-shabon-19-320.jpg)

![G. Leading Change

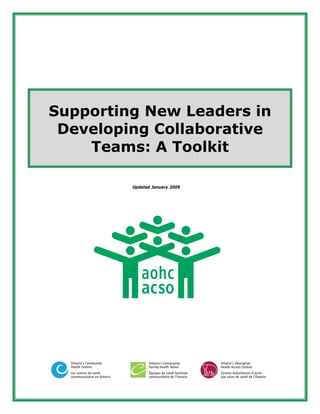

Leading change is frequently a challenge for leaders. If you are the leader of a new initiative, health

centre or family health team you are likely leading a change of some kind. The need to respond to

community needs and a rapidly changing policy environment as well as the tremendous challenges to

the health-care system means that change may be occurring at many levels within an organization,

often simultaneously. To help you think about the kind of change you are leading and the supports that

could be used by team members, you can consider whether the change is developmental, transitional

or transformational.21

Developmental change aims to change an existing situation or process through enhancement. This

type of change may seek to improve communication, team work or implement an improvement such as

a new process or technique. In developmental change the goal or desired outcome of the change is

clear. The leader supports developmental change by providing information that shares the rationale for

the needed change and by assisting with the setting of new goals that stretch team members while also

ensuring that the resources and support for meeting the new goal are in place.

Transitional change is characterized by the need to “replace what is with something entirely

different.”22 This order of change requires leaders to recognize that something completely different is

required in order to respond to an opportunity or challenge. Examples of transitional change include the

introduction of new programs or implementing new technologies that are similar to existing ones.

Transitional change may not require high levels of change from the people involved or within the

workplace culture. The leader uses clear communication, participation of the affected people and their

control over the implementation to achieve the desired new state. The leader supports transitional

change by identifying the differences between the existing and desired outcomes. The leader can

facilitate the identification of anything that can be brought forward to serve the new situation, what will

have to be left behind or is no longer needed, and what new components will be created to complete

the new state. This type of change is often implemented with a parallel structure: one to keep existing

operations going and another to manage the stages of planning and implementing the required

changes.

The third type of change is transformational change. This type of change is marked by high levels of

uncertainty and complexity that will require attitude, behaviour and cultural changes from all involved.

The final result or outcome may not be known and the “scope of this change [is] so significant that it

requires the organization’s culture and people’s behaviour and mindsets to shift fundamentally in order

to implement the changes successfully and succeed in the new state.”23 In transformational change,

the result emerges from a chaotic or unstable state. The leader’s role in transformational change is to

monitor all sources of feedback to continually assess the process and direction of the change and adjust

the course to continue in the desired direction. The leader becomes an adept learner to interpret and

act on the feedback and facilitates learning in others.

21

Anderson, D and Ackerman Anderson, L. (2001) Beyond Change Management: Advanced Strategies for Today’s

Transformational Leaders. Jossey/Bass – Pfeiffer.

22

Anderson and Ackerman Anderson, p. 35.

23

Anderson and Ackerman Anderson, p. 39.

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/collaborativeteamstoolkitmar2009drshabon-120820202121-phpapp01/85/Collaborative-teams-toolkit-mar-2009-dr-shabon-20-320.jpg)

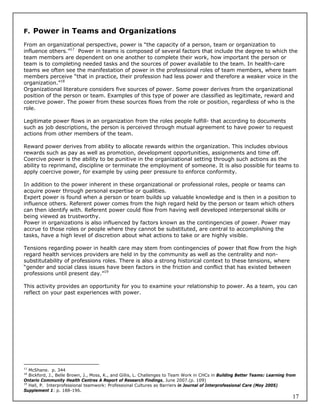

![1 2 3 4 5

We don’t have We have some objectives We have

either and/or some measures both

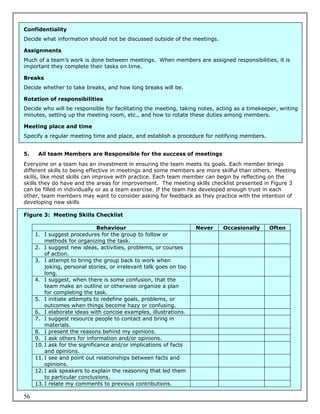

8. Empowerment plan: Does the team have a clear picture of which decisions it can make and which

require management approval?

1 2 3 4 5

There is no We are clear about We are clear about how

empowerment some items empowered we are

plan

9. Roles and responsibilities: Are you clear about what’s expected of you and how your role relates to

the roles of other team members?

1 2 3 4 5

I’m unclear I’m somewhat clear I’m totally clear

10. Communication plan: Does the team have a plan that describes who it should communicate with,

when, and how?

1 2 3 4 5

No plans Somewhat planned We have a plan

Comments:

Return the completed survey to:

[Insert contact information]

Team members seek opportunities to define roles and responsibilities during the team formation stage.

Team members “may be unclear about their expectations of each other, and group leader’s

expectations of them; and are probably unsure about the roles each of them will play in the work of the

group.”35 Team members will want to discuss their roles and responsibilities, often with a heavy

emphasis on their tasks. Some people respond to the uncertainty of the forming stage by “want[ing]

every task defined and allocated to someone and their own job, responsibilities and powers clearly

defined.”36 Payne cautions that this is a polarity: there may not be a right answer, rather, the team

needs to find a balance between too much uncertainty or too much constraint leading to unnecessary

bureaucracy. He suggests five categories for considering team priorities, specialization and workload

allocation and notes that in practice these categories are often combined with factors such as

geographic location and team member skills and interests to create a complex system for defining roles

and responsibilities:

legal requirements

types of work (for example, group work, cognitive-behavioural therapy)

service user categories (for example, client problems)

levels of risk, difficulty or complexity

organizational or political policies (for example, performance indicators)

C. Dimensions of Team Roles

35

Laiken, M. 1994)

36

Payne, M. (2000) p. 86.

34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/collaborativeteamstoolkitmar2009drshabon-120820202121-phpapp01/85/Collaborative-teams-toolkit-mar-2009-dr-shabon-35-320.jpg)