The document discusses several topics related to counseling children and adolescents including:

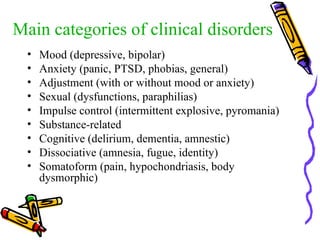

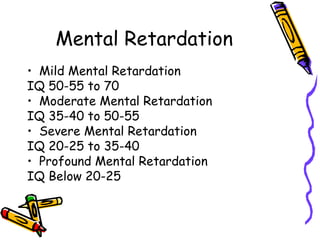

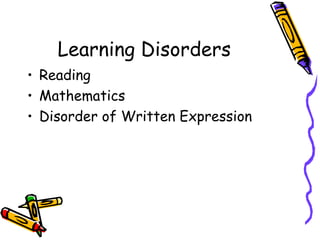

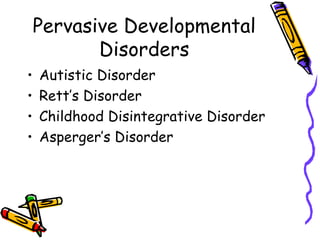

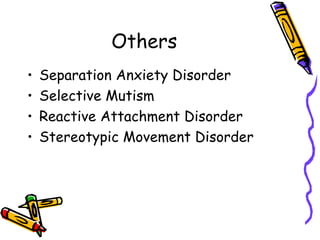

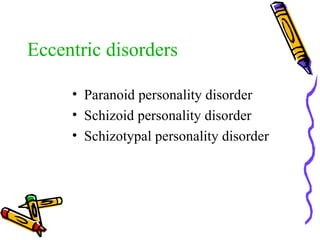

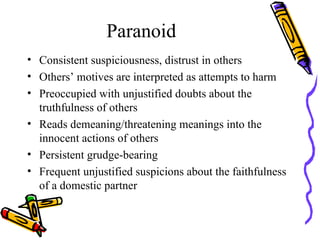

- Common clinical disorders diagnosed in children and adolescents such as mood disorders, anxiety disorders, ADHD, and autism spectrum disorders.

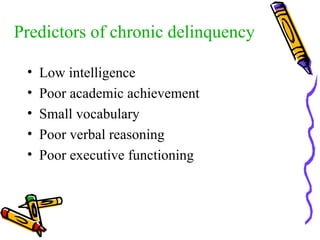

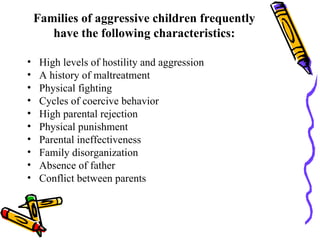

- Factors that influence juvenile delinquency such as low intelligence, poor academic achievement, family dysfunction, and lack of basic needs.

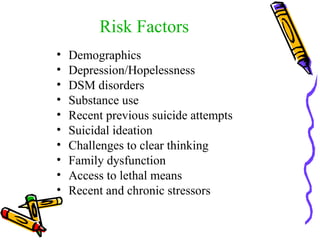

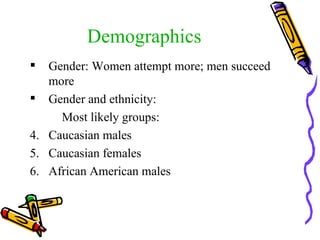

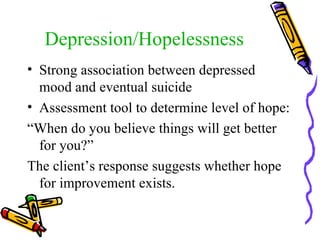

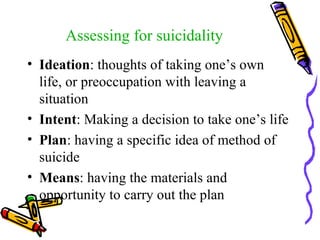

- The importance of assessing suicide risk in children and adolescents by evaluating ideation, intent, plans, means, as well as demographic, psychological and environmental risk factors.

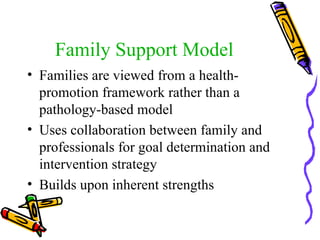

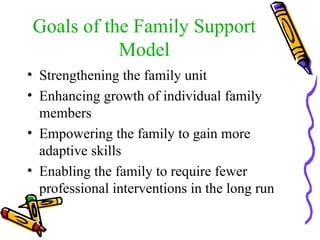

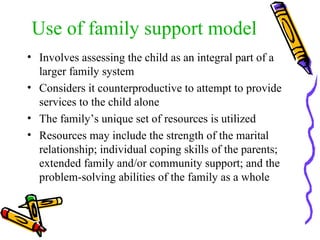

- The benefits of using a family support model for intervention which views the family as a system and builds on family strengths rather than focusing solely on the child's problems.