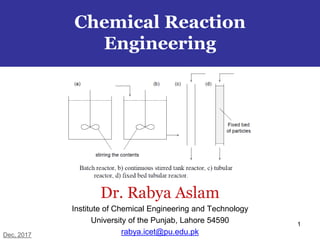

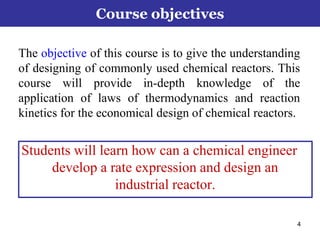

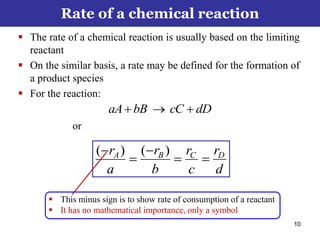

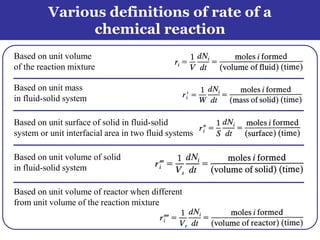

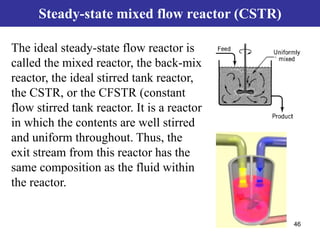

This document outlines the course contents, objectives, and topics for a Chemical Reaction Engineering course. The course will cover topics such as kinetics of homogeneous and heterogeneous reactions, reactor design including batch, mixed flow, plug flow, and catalytic reactors. Students will learn how to develop rate expressions and design industrial reactors by applying principles of thermodynamics and reaction kinetics. The objective is to provide an in-depth understanding of commonly used chemical reactor designs.