This document provides an overview of atomic structure and chemical bonding. It discusses the following key points:

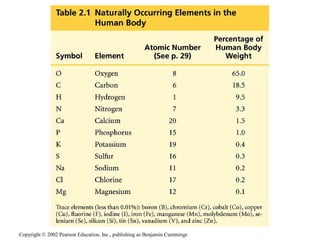

- About 25 elements are essential for life, with carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, and nitrogen making up 96% of living matter.

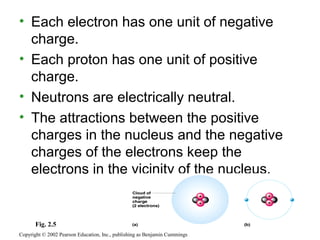

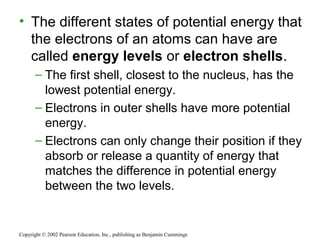

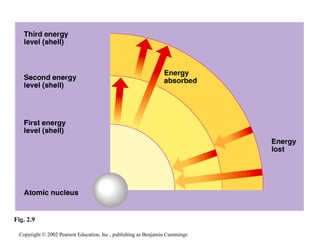

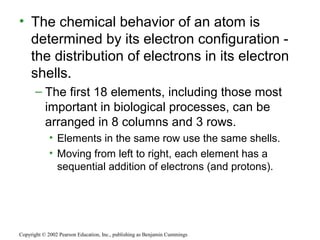

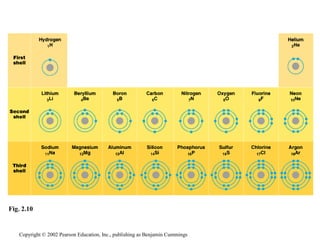

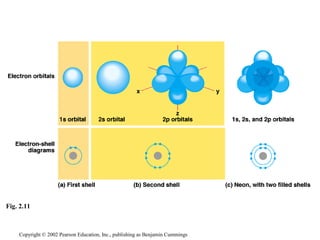

- Atoms are composed of protons, neutrons, and electrons. Chemical behavior is determined by the atom's electron configuration.

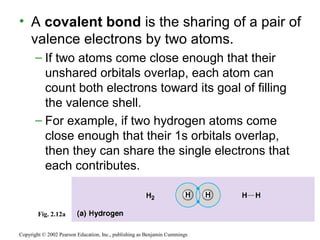

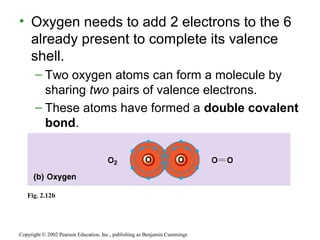

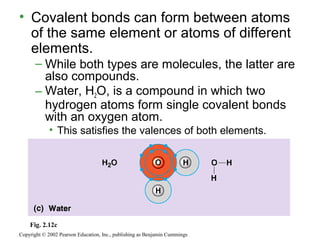

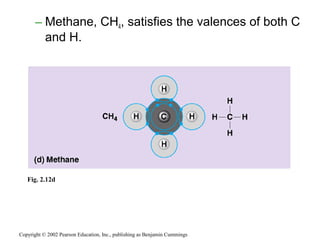

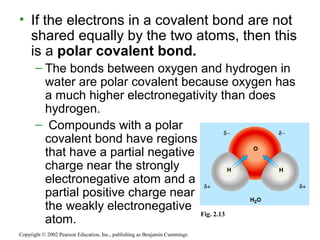

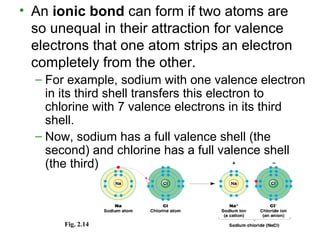

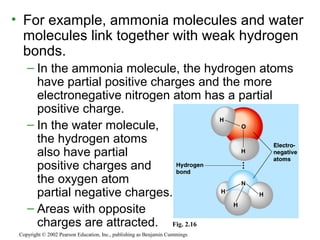

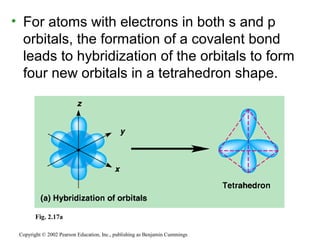

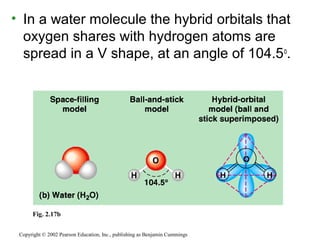

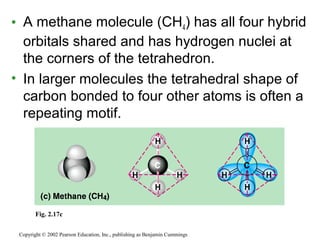

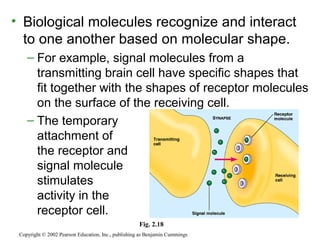

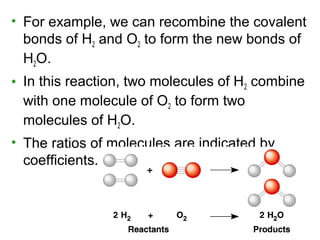

- Atoms combine via covalent bonds, which involve sharing electrons, and ionic bonds, which involve electron transfer. Weak bonds like hydrogen bonds also play important roles in biology.

- Covalent bonds form molecules, while ionic bonds form crystalline ionic compounds. Bond type depends on differences in electronegativity between atoms.