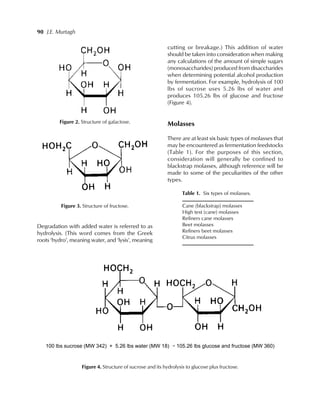

This document discusses molasses as a feedstock for alcohol production. It begins by explaining that molasses differs from other feedstocks like corn or potatoes in that its carbohydrates are already in the form of sugars and do not need to be broken down. It then provides details on the basic sugar chemistry in molasses and the different types of molasses. The majority of the document focuses on describing the production and properties of blackstrap molasses, which is the type generally used for alcohol production. It concludes by discussing the economics and fermentation process involved in using blackstrap molasses to produce ethanol.