More Related Content

PDF

PPTX

Software Testing Introduction (Part 1) PDF

Introduction To Software Testing 2nd Edition Paul Ammann Jeff Offutt PDF

Introduction to Software Testing.pdf PPTX

Ch09-4-modelBased.pptxhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh PDF

ConsolidatedSlides (1).pdf PPT

Software Testing - Introduction - Program based grammars DOC

Testing survey by_directions Similar to Ch09-5-inputs.pptx ccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccc

PDF

Software testing: an introduction - 2017 PDF

Engineering Software Products: 9. testing PDF

Testing Slides 1 (Testing Intro+Static Testing).pdf PPTX

Cheat sheet BSC computer science 3rd yr.pptx PPTX

SE - Lecture 8 - Software Testing State Diagram.pptx PPTX

Software Testing from Unit-IV CIC-309 Btech PDF

software-testing-yogesh-singh (1).pdf PPT

Chapter 6,7 Software coding and Testing.ppt PPTX

PPTX

PPT

preliminaries-raytheon.ppt introductione PPT

preliminaries-raytheon.ppt introductione ODP

PPT

PPT

PDF

PPT

Darius Silingas - From Model Driven Testing to Test Driven Modelling PDF

Model-Driven Testing For Agile Teams PDF

[JS EXPERIENCE 2018] “Who watches the watchmen": Testando nossos testes - Mar... PPTX

More from VaibhavSrivastav52

PPTX

python_module_................................................................. PPTX

Ch07-3-sourceCode.pptxhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh PPTX

RDBMS PARUL UNIVERSITY VADODARA BTECH CSE PPTX

advanced database management system by uni PPTX

rdbms1-191014080818000000000000000000000000000000000 PPTX

rdbms3, dbms,dbms,rdbmssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssss PPTX

advanced database management system by uni PPTX

dbms ppt parul university dbms course for PPTX

S-VYASA dbms111111111111111111111111111111111111111 PPTX

S-VYASA STQA-1.pptx00000000000000000000000000000000 PPTX

python_module_4.................................... PPTX

PPT-1.pptxpppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppp PPTX

PPT-2.pptxpppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppp PPTX

PPT-3.pptxppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppp PPTX

rdbms parul university oracle dbms bca mca PPTX

python_module_........................................ PPTX

python_module_3.................................... Ch09-5-inputs.pptx ccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccc

- 1.

- 2.

© Ammann &Offutt 2

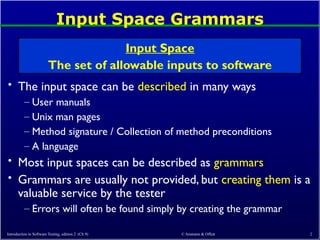

Input Space Grammars

• The input space can be described in many ways

– User manuals

– Unix man pages

– Method signature / Collection of method preconditions

– A language

• Most input spaces can be described as grammars

• Grammars are usually not provided, but creating them is a

valuable service by the tester

– Errors will often be found simply by creating the grammar

Input Space

The set of allowable inputs to software

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

- 3.

© Ammann &Offutt 3

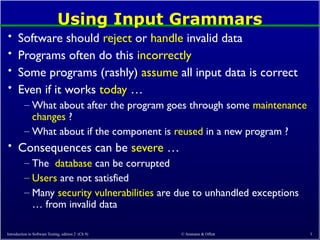

Using Input Grammars

• Software should reject or handle invalid data

• Programs often do this incorrectly

• Some programs (rashly) assume all input data is correct

• Even if it works today …

– What about after the program goes through some maintenance

changes ?

– What about if the component is reused in a new program ?

• Consequences can be severe …

– The database can be corrupted

– Users are not satisfied

– Many security vulnerabilities are due to unhandled exceptions

… from invalid data

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

- 4.

© Ammann &Offutt 4

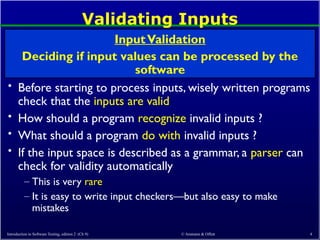

Validating Inputs

• Before starting to process inputs, wisely written programs

check that the inputs are valid

• How should a program recognize invalid inputs ?

• What should a program do with invalid inputs ?

• If the input space is described as a grammar, a parser can

check for validity automatically

– This is very rare

– It is easy to write input checkers—but also easy to make

mistakes

InputValidation

Deciding if input values can be processed by the

software

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

- 5.

© Ammann &Offutt 5

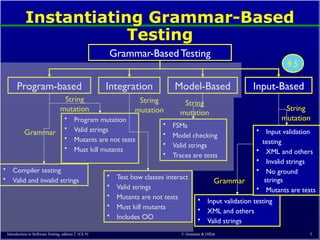

Instantiating Grammar-Based

Testing

Grammar-Based Testing

Program-based Integration Model-Based Input-Based

• Compiler testing

• Valid and invalid strings

Grammar

String

mutation

• Program mutation

• Valid strings

• Mutants are not tests

• Must kill mutants

• Input validation testing

• XML and others

• Valid strings

Grammar

• Test how classes interact

• Valid strings

• Mutants are not tests

• Must kill mutants

• Includes OO

String

mutation

• FSMs

• Model checking

• Valid strings

• Traces are tests

String

mutation

• Input validation

testing

• XML and others

• Invalid strings

• No ground

strings

• Mutants are tests

String

mutation

9.5

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

- 6.

Input Space BNFGrammars (9.5.1)

• Input spaces can be expressed in many forms

• A common way is to use some form of grammar

• We will look at three grammar-based ways to describe

input spaces

1. Regular expressions

2. BNF grammars

3. XML and Schema

• All are similar and can be used in different contexts

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9) © Ammann & Offutt 6

- 7.

© Ammann &Offutt 7

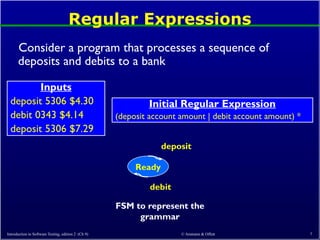

Regular Expressions

Consider a program that processes a sequence of

deposits and debits to a bank

Inputs

deposit 5306 $4.30

debit 0343 $4.14

deposit 5306 $7.29

Initial Regular Expression

(deposit account amount | debit account amount) *

Ready

deposit

debit

FSM to represent the

grammar

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

- 8.

© Ammann &Offutt 8

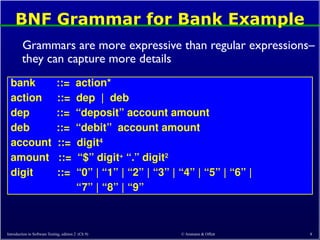

BNF Grammar for Bank Example

Grammars are more expressive than regular expressions–

they can capture more details

bank ::= action*

action ::= dep | deb

dep ::= “deposit” account amount

deb ::= “debit” account amount

account ::= digit4

amount ::= “$” digit+

“.” digit2

digit ::= “0” | “1” | “2” | “3” | “4” | “5” | “6” |

“7” | “8” | “9”

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

- 9.

© Ammann &Offutt 9

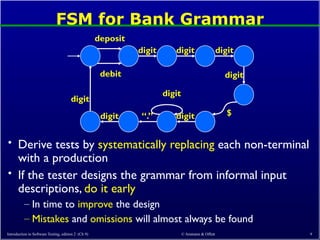

FSM for Bank Grammar

• Derive tests by systematically replacing each non-terminal

with a production

• If the tester designs the grammar from informal input

descriptions, do it early

– In time to improve the design

– Mistakes and omissions will almost always be found

deposit

debit

digit

digit

digit

digit

“.”

digit

digit

digit

$

digit

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

- 10.

© Ammann &Offutt 10

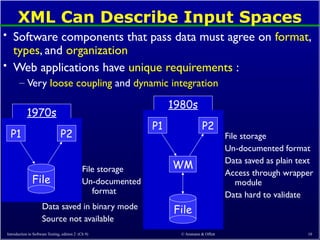

XML Can Describe Input Spaces

• Software components that pass data must agree on format,

types, and organization

• Web applications have unique requirements :

– Very loose coupling and dynamic integration

1970s

style

P1 P2

File

File storage

Un-documented

format

Data saved in binary mode

Source not available

1980s

style

P1 P2

File

WM

File storage

Un-documented format

Data saved as plain text

Access through wrapper

module

Data hard to validate

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

- 11.

© Ammann &Offutt 11

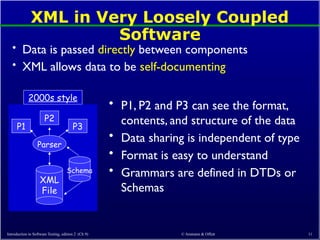

XML in Very Loosely Coupled

Software

• Data is passed directly between components

• XML allows data to be self-documenting

• P1, P2 and P3 can see the format,

contents, and structure of the data

• Data sharing is independent of type

• Format is easy to understand

• Grammars are defined in DTDs or

Schemas

2000s style

Schema

P1

P2

Parser

XML

File

P3

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

- 12.

© Ammann &Offutt 12

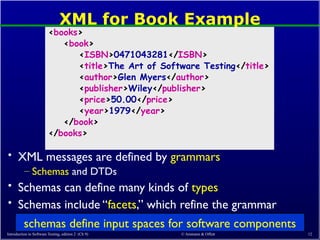

XML for Book Example

• XML messages are defined by grammars

– Schemas and DTDs

• Schemas can define many kinds of types

• Schemas include “facets,” which refine the grammar

<books>

<book>

<ISBN>0471043281</ISBN>

<title>The Art of Software Testing</title>

<author>Glen Myers</author>

<publisher>Wiley</publisher>

<price>50.00</price>

<year>1979</year>

</book>

</books>

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

schemas define input spaces for software components

- 13.

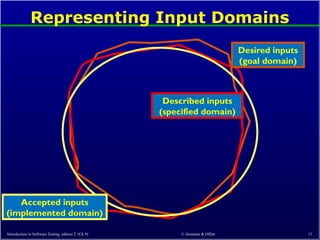

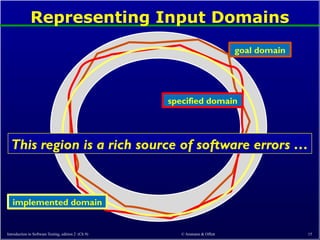

Representing Input Domains

Introductionto Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9) © Ammann & Offutt 13

Desired inputs

(goal domain)

Described inputs

(specified domain)

Accepted inputs

(implemented domain)

- 14.

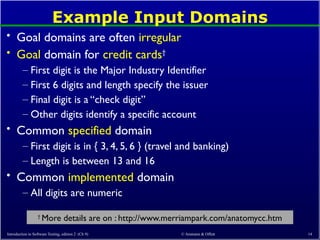

Example Input Domains

•Goal domains are often irregular

• Goal domain for credit cards†

– First digit is the Major Industry Identifier

– First 6 digits and length specify the issuer

– Final digit is a “check digit”

– Other digits identify a specific account

• Common specified domain

– First digit is in { 3, 4, 5, 6 } (travel and banking)

– Length is between 13 and 16

• Common implemented domain

– All digits are numeric

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9) © Ammann & Offutt 14

†

More details are on : http://www.merriampark.com/anatomycc.htm

- 15.

Representing Input Domains

Introductionto Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9) © Ammann & Offutt 15

goal domain

specified domain

implemented domain

This region is a rich source of software errors …

- 16.

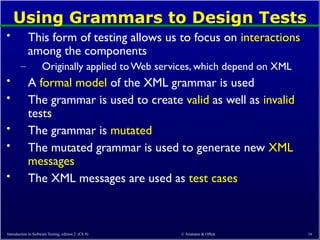

Using Grammars toDesign Tests

• This form of testing allows us to focus on interactions

among the components

– Originally applied toWeb services, which depend on XML

• A formal model of the XML grammar is used

• The grammar is used to create valid as well as invalid

tests

• The grammar is mutated

• The mutated grammar is used to generate new XML

messages

• The XML messages are used as test cases

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9) © Ammann & Offutt 16

- 17.

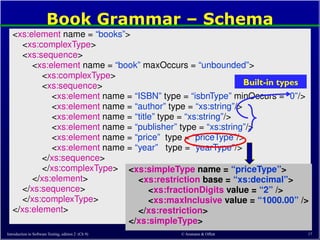

© Ammann &Offutt 17

Book Grammar – Schema

<xs:element name = “books”>

<xs:complexType>

<xs:sequence>

<xs:element name = “book” maxOccurs = “unbounded”>

<xs:complexType>

<xs:sequence>

<xs:element name = “ISBN” type = “isbnType” minOccurs = “0”/>

<xs:element name = “author” type = “xs:string”/>

<xs:element name = “title” type = “xs:string”/>

<xs:element name = “publisher” type = “xs:string”/>

<xs:element name = “price” type = “priceType”/>

<xs:element name = “year” type = “yearType”/>

</xs:sequence>

</xs:complexType>

</xs:element>

</xs:sequence>

</xs:complexType>

</xs:element>

<xs:simpleType name = “priceType”>

<xs:restriction base = “xs:decimal”>

<xs:fractionDigits value = “2” />

<xs:maxInclusive value = “1000.00” />

</xs:restriction>

</xs:simpleType>

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

Built-in types

- 18.

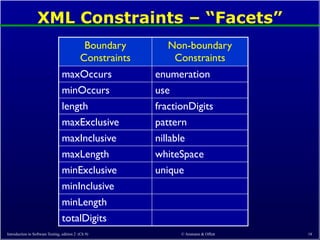

XML Constraints –“Facets”

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9) © Ammann & Offutt 18

Boundary

Constraints

Non-boundary

Constraints

maxOccurs enumeration

minOccurs use

length fractionDigits

maxExclusive pattern

maxInclusive nillable

maxLength whiteSpace

minExclusive unique

minInclusive

minLength

totalDigits

- 19.

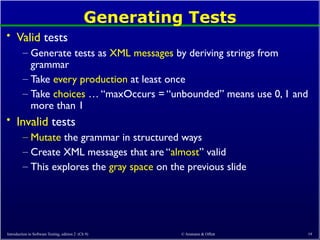

Generating Tests

• Validtests

– Generate tests as XML messages by deriving strings from

grammar

– Take every production at least once

– Take choices … “maxOccurs = “unbounded” means use 0, 1 and

more than 1

• Invalid tests

– Mutate the grammar in structured ways

– Create XML messages that are “almost” valid

– This explores the gray space on the previous slide

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9) © Ammann & Offutt 19

- 20.

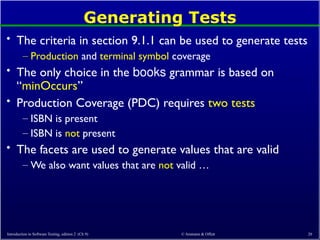

© Ammann &Offutt 20

Generating Tests

• The criteria in section 9.1.1 can be used to generate tests

– Production and terminal symbol coverage

• The only choice in the books grammar is based on

“minOccurs”

• Production Coverage (PDC) requires two tests

– ISBN is present

– ISBN is not present

• The facets are used to generate values that are valid

– We also want values that are not valid …

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

- 21.

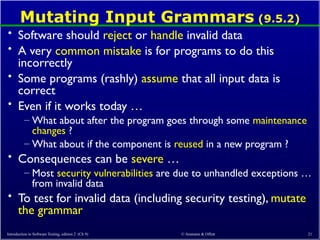

© Ammann &Offutt 21

Mutating Input Grammars (9.5.2)

• Software should reject or handle invalid data

• A very common mistake is for programs to do this

incorrectly

• Some programs (rashly) assume that all input data is

correct

• Even if it works today …

– What about after the program goes through some maintenance

changes ?

– What about if the component is reused in a new program ?

• Consequences can be severe …

– Most security vulnerabilities are due to unhandled exceptions …

from invalid data

• To test for invalid data (including security testing), mutate

the grammar

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

- 22.

© Ammann &Offutt 22

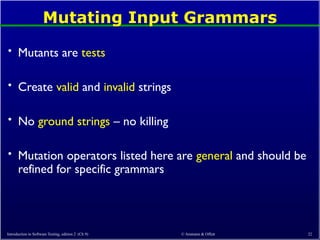

Mutating Input Grammars

• Mutants are tests

• Create valid and invalid strings

• No ground strings – no killing

• Mutation operators listed here are general and should be

refined for specific grammars

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

- 23.

© Ammann &Offutt 23

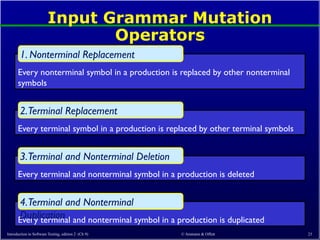

Input Grammar Mutation

Operators

Every nonterminal symbol in a production is replaced by other nonterminal

symbols

1. Nonterminal Replacement

Every terminal symbol in a production is replaced by other terminal symbols

2.Terminal Replacement

Every terminal and nonterminal symbol in a production is deleted

3.Terminal and Nonterminal Deletion

Every terminal and nonterminal symbol in a production is duplicated

4.Terminal and Nonterminal

Duplication

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

- 24.

© Ammann &Offutt 24

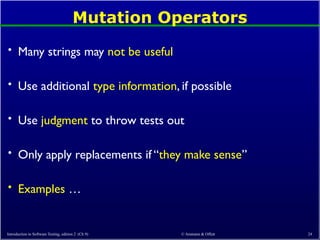

Mutation Operators

• Many strings may not be useful

• Use additional type information, if possible

• Use judgment to throw tests out

• Only apply replacements if “they make sense”

• Examples …

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

- 25.

© Ammann &Offutt 25

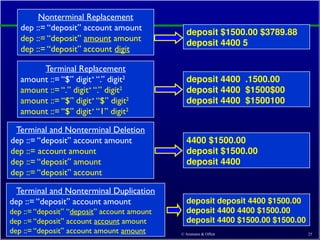

Nonterminal Replacement

dep ::= “deposit” account amount

dep ::= “deposit” amount amount

dep ::= “deposit” account digit

deposit $1500.00 $3789.88

deposit 4400 5

Terminal Replacement

amount ::= “$” digit+

“.” digit2

amount ::= “.” digit+

“.” digit2

amount ::= “$” digit+

“$” digit2

amount ::= “$” digit+

“1” digit2

deposit 4400 .1500.00

deposit 4400 $1500$00

deposit 4400 $1500100

Terminal and Nonterminal Deletion

dep ::= “deposit” account amount

dep ::= account amount

dep ::= “deposit” amount

dep ::= “deposit” account

4400 $1500.00

deposit $1500.00

deposit 4400

deposit deposit 4400 $1500.00

deposit 4400 4400 $1500.00

deposit 4400 $1500.00 $1500.00

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

Terminal and Nonterminal Duplication

dep ::= “deposit” account amount

dep ::= “deposit” “deposit” account amount

dep ::= “deposit” account account amount

dep ::= “deposit” account amount amount

- 26.

© Ammann &Offutt 26

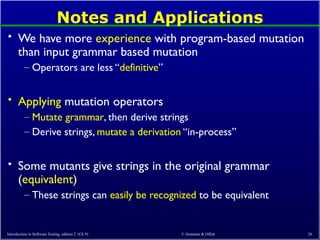

Notes and Applications

• We have more experience with program-based mutation

than input grammar based mutation

– Operators are less “definitive”

• Applying mutation operators

– Mutate grammar, then derive strings

– Derive strings, mutate a derivation “in-process”

• Some mutants give strings in the original grammar

(equivalent)

– These strings can easily be recognized to be equivalent

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

- 27.

© Ammann &Offutt 27

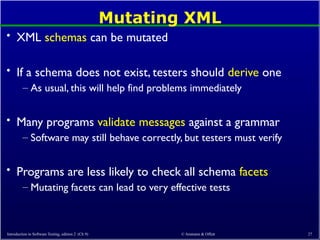

Mutating XML

• XML schemas can be mutated

• If a schema does not exist, testers should derive one

– As usual, this will help find problems immediately

• Many programs validate messages against a grammar

– Software may still behave correctly, but testers must verify

• Programs are less likely to check all schema facets

– Mutating facets can lead to very effective tests

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

- 28.

© Ammann &Offutt 28

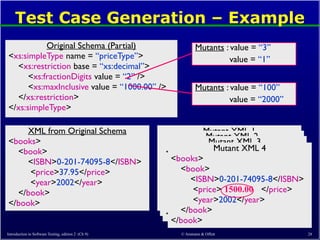

Test Case Generation – Example

Original Schema (Partial)

<xs:simpleType name = “priceType”>

<xs:restriction base = “xs:decimal”>

<xs:fractionDigits value = “2” />

<xs:maxInclusive value = “1000.00” />

</xs:restriction>

</xs:simpleType>

Mutants : value = “3”

value = “1”

Mutants : value = “100”

value = “2000”

XML from Original Schema

<books>

<book>

<ISBN>0-201-74095-8</ISBN>

<price>37.95</price>

<year>2002</year>

</book>

</book>

Mutant XML 1

<books>

<book>

<ISBN>0-201-74095-8</ISBN>

<price>37.95 </price>

<year>2002</year>

</book>

</book>

505

Mutant XML 2

<books>

<book>

<ISBN>0-201-74095-8</ISBN>

<price>37.95</price>

<year>2002</year>

</book>

</book>

5

Mutant XML 3

<books>

<book>

<ISBN>0-201-74095-8</ISBN>

<price>37.95 </price>

<year>2002</year>

</book>

</book>

99.00

Mutant XML 4

<books>

<book>

<ISBN>0-201-74095-8</ISBN>

<price>37.95 </price>

<year>2002</year>

</book>

</book>

1500.00

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)

- 29.

© Ammann &Offutt 29

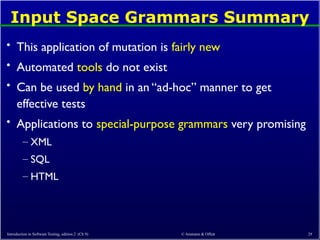

Input Space Grammars Summary

• This application of mutation is fairly new

• Automated tools do not exist

• Can be used by hand in an “ad-hoc” manner to get

effective tests

• Applications to special-purpose grammars very promising

– XML

– SQL

– HTML

Introduction to Software Testing, edition 2 (Ch 9)