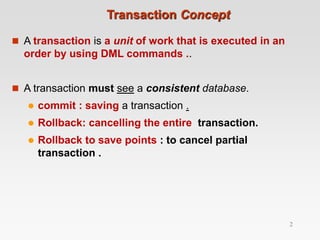

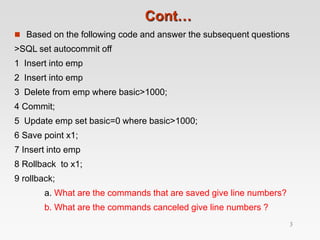

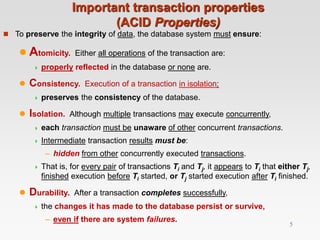

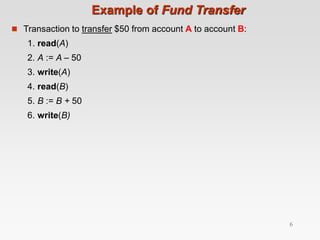

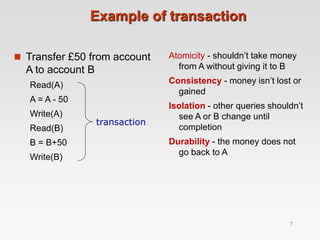

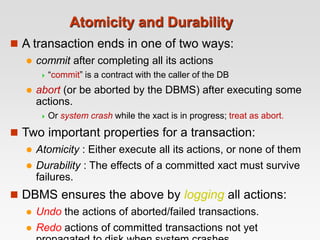

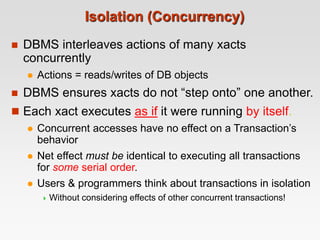

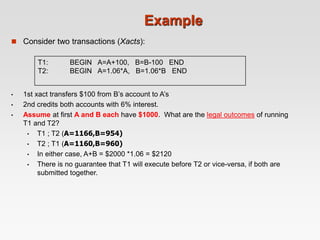

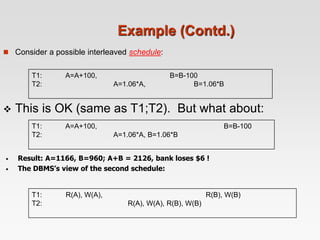

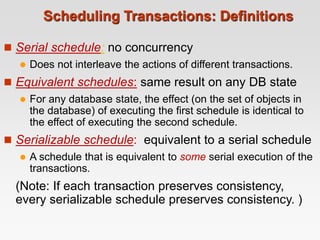

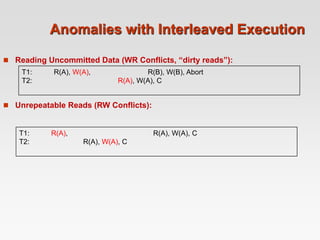

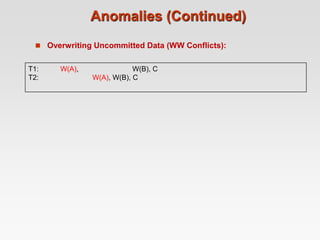

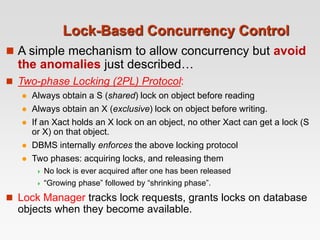

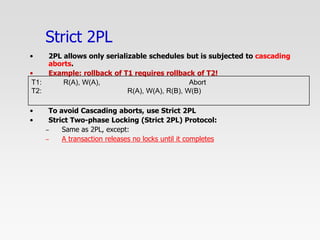

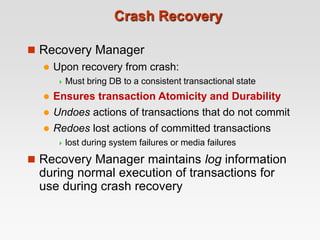

The document discusses transaction concepts, concurrency control, and recovery in database systems. It defines a transaction as a unit of work executed using DML commands that must see a consistent database. Concurrency control techniques like locking protocols ensure transactions execute reliably in the presence of concurrent access. Recovery managers use transaction logging to restore the database to a consistent state after failures and abort uncommitted transactions.