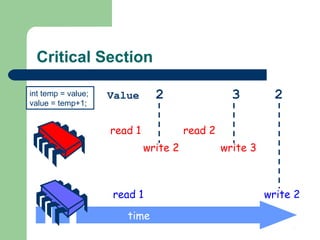

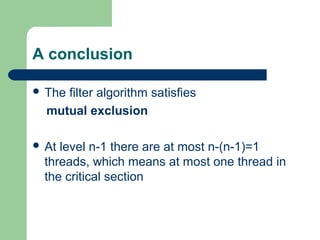

The document discusses algorithms for solving the mutual exclusion problem in multithreaded programs. It begins by describing two inadequate algorithms for two threads that fail to guarantee deadlock freedom. It then presents Peterson's algorithm and Kessels' single-writer algorithm, proving they satisfy mutual exclusion, deadlock freedom, and starvation freedom for two threads. The document also discusses using tournament algorithms and the filter algorithm to generalize two-thread solutions to work for multiple threads by having threads progress through levels like a tournament bracket.

![Algorithm 1

Thread 0

flag[0] = true

while (flag[1]) {}

critical section

flag[0]=false

Thread 1

flag[1] = true

while (flag[0]) {}

critical section

flag[1]=false](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-10-320.jpg)

![Proof

Assume in the contrary that two threads can be in their critical

section at the same time.

From the code we can see:

write0(flag[0]=true) read0(flag[1]==false) CS0

write1(flag[1]=true) read1(flag[0]==false) CS1

From the assumption:

read0(flag[1]==false) write1(flag[1]=true)

Thread 0

flag[0] = true

while (flag[1]) {}

critical section

flag[0]=false

Thread 1

flag[1] = true

while (flag[0]) {}

critical section

flag[1]=false](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-12-320.jpg)

![Proof

We get:

write0(flag[0]=true) read0(flag[1]==false)

write1(flag[1]=true) read1(flag[0]==false)

That means that thread 0 writes (flag[0]=true) and then thread 1

reads that (flag[0]==false), a contradiction.

Thread 0

flag[0] = true

while (flag[1]) {}

critical section

flag[0]=false

Thread 1

flag[1] = true

while (flag[0]) {}

critical section

flag[1]=false](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-13-320.jpg)

![Deadlock freedom

Thread 0

flag[0] = true

while (flag[1]) {}

critical section

flag[0]=false

Thread 1

flag[1] = true

while (flag[0]) {}

critical section

flag[1]=false

Algorithm 1 fails dead-lock freedom:

Concurrent execution can deadlock.

If both threads write flag[0]=true and flag[1]=true

before reading (flag[0]) and (flag[1]) then both

threads wait forever.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-14-320.jpg)

![Peterson’s Algorithm

Thread 0

flag[0] = true

victim = 0

while (flag[1] and victim == 0)

}skip{

critical section

flag[0] = false

Thread 1

flag[1] = true

victim = 1

while (flag[0] and victim == 1)

}skip{

critical section

flag[1] = false](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-21-320.jpg)

![Peterson’s Algorithm

0/1 indicates that the thread is contending for the critical

section by setting flag[0]/flag[1] to true.

victim shows who got last

Then if the value of flag[i] is true then there is no contending

by other thread and the thread can start executing the critical

section. Otherwise the first who writes to victim is also the

first to get into the critical section

Thread 0

flag[0] = true

victim = 0

while (flag[1] and

victim == 0) }skip{

critical section

flag[0] = false

Thread 1

flag[1] = true

victim = 1

while (flag[0] and

victim == 1) }skip{

critical section

flag[1] = false](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-22-320.jpg)

![Schematic for Peterson’s mutual exclusion algorithmSchematic for Peterson’s mutual exclusion algorithm

Indicate contending

flag[i] := true

Indicate contending

flag[i] := true

Barrier

victim := i

Barrier

victim := i

Contention?

flag[j] = true ?

Contention?

flag[j] = true ?

critical sectioncritical section

exit code

flag[i] = false

exit code

flag[i] = false

First to cross

the barrier?

victim = j ?

First to cross

the barrier?

victim = j ?yes

yes

no / maybe

no

The structure shows that the

first thread to cross the barrier is

the one which gets to enter the

critical section. When there is no

contention a thread can enter the

critical section immediately.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-23-320.jpg)

![Proof

Assume in the contrary that two threads can be in their

critical section at the same time.

From the code we see:

(*) write0(flag[0]=true) write0(victim=0)

read0(flag[1]) read0(victim) CS0

write1(flag[1]=true) write1(victim=1) read1(flag[0])

read1(victim) CS1

Thread 0

flag[0] = true

victim = 0

while (flag[1] and

victim == 0) }skip{

critical section

flag[0] = false

Thread 1

flag[1] = true

victim = 1

while (flag[0] and

victim == 1) }skip{

critical section

flag[1] = false](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-25-320.jpg)

![Proof

Assume that the last thread to write to victim was 0. Then:

write1(victim=1) write0(victim=0)

This implies that thread 0 read that victim=0 in equation (*)

Since thread 0 is in the critical section, it must have read

flag[1] as false, so:

write0(victim=0) read0(flag[1]==false)

Thread 0

flag[0] = true

victim = 0

while (flag[1] and

victim == 0) }skip{

critical section

flag[0] = false

Thread 1

flag[1] = true

victim = 1

while (flag[0] and

victim == 1) }skip{

critical section

flag[1] = false](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-26-320.jpg)

![Proof

Then, we get:

write1(flag[1]=true) write1(victim=1)

write0(victim=0) read0(flag[1]==false)

Thus:

write1(flag[1]=true) read0(flag[1]==false)

There was no other write to flag[1] before the critical

section execution and this yields a contradiction.

Thread 0

flag[0] = true

victim = 0

while (flag[1] and

victim == 0) }skip{

critical section

flag[0] = false

Thread 1

flag[1] = true

victim = 1

while (flag[0] and

victim == 1) }skip{

critical section

flag[1] = false](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-27-320.jpg)

![Proof

Assume to the contrary that the algorithm is not

starvation-free

Then one of the threads, say thread 0, is forced to

remain in its entry code forever

Thread 0

flag[0] = true

victim = 0

while (flag[1] and

victim == 0) }skip{

critical section

flag[0] = false

Thread 1

flag[1] = true

victim = 1

while (flag[0] and

victim == 1) }skip{

critical section

flag[1] = false](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-29-320.jpg)

![Proof

This implies that at some later point thread 1 will do

one of the following three things:

1. Stay in its remainder forever

2. Stay in its entry code forever, not succeeding and

proceeding into its critical section

3. Repeatedly enter and exit its critical section

Thread 0

flag[0] = true

victim = 0

while (flag[1] and

victim == 0) }skip{

critical section

flag[0] = false

Thread 1

flag[1] = true

victim = 1

while (flag[0] and

victim == 1) }skip{

critical section

flag[1] = false

We’ll show that each of

the three possible cases

leads to a contradiction.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-30-320.jpg)

![Proof

In the first case flag[1] is false, and hence thread 0 can

proceed.

The second case is impossible since victim is either 0 or 1, and

hence it always enables at least one of the threads to proceed.

In the third case, when thread 1 exit its critical section and tries

to enter its critical section again, it will set victim to 1 and will

never change it back to 0, enabling thread 0 to proceed.

Thread 0

flag[0] = true

victim = 0

while (flag[1] and

victim == 0) }skip{

critical section

flag[0] = false

Thread 1

flag[1] = true

victim = 1

while (flag[0] and

victim == 1) }skip{

critical section

flag[1] = false](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-31-320.jpg)

![Kessels’ single-writer Algorithm

What if we replace the multi-writer register victim with two single-

writer registers. What is new algorithm?

Answer (Kessels’ Alg.)

victim = 0 victim[0] =victim[1]

victim = 1 victim[0] ≠victim[1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-32-320.jpg)

![Kessels’ single-writer Algorithm

Thread 0

flag[0] = true

local[0] = victim[1]

victim[0] = local[0]

while (flag[1] and

local[0]=victim[1]) }skip{

critical section

flag[0] = false

Thread 1

flag[1] = true

local[1]=1-victim[0]

victim[1] = local[1]

while (flag[0] and

local[1] ≠ victim[0])) }skip{

critical section

flag[1] = false

Thread 0 can write the registers victim[0] and flag[0]

and read the registers victim[1] and flag[1]

Thread 1 can write the registers victim[1] and flag[1]

and read the registers victim[0] and flag[0]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-33-320.jpg)

![The Filter Algorithm for n Threads

A direct generalization of Peterson’s algorithm

to multiple threads.

The Peterson algorithm used a two-element

boolean flag array to indicate whether a

thread is interested in entering the critical

section. The filter algorithm generalizes this

idea with an N-element integer level array,

where the value of level[i] indicates the latest

level that thread i is interested in entering.

ncs

cslevel n-1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-37-320.jpg)

![The Filter Algorithm

Thread i

for (int L = 1; L < n; L++) {

level[i] = L;

victim[L] = i;

while ((∃ k != i level[k] >= L) and victim[L] == i ) {}

}

critical section

level[i] = 0;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-39-320.jpg)

![Thread i

for (int L = 1; L < n; L++) {

level[i] = L;

victim[L] = i;

while ((∃ k != i level[k] >= L) and victim[L] == i ) {}

}

critical section

level[i] = 0;

Filter

One level at a time](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-40-320.jpg)

![Filter

Thread i

for (int L = 1; L < n; L++) {

level[i] = L;

victim[L] = i;

while ((∃ k != i level[k] >= L) and victim[L] == i ) {}

}

critical section

level[i] = 0;

Announce intention to enter level L](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-41-320.jpg)

![Filter

Thread i

for (int L = 1; L < n; L++) {

level[i] = L;

victim[L] = i;

while ((∃ k != i level[k] >= L) and victim[L] == i ) {}

}

critical section

level[i] = 0;

Give priority to anyone but me (at every level)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-42-320.jpg)

![Filter

Thread i

for (int L = 1; L < n; L++) {

level[i] = L;

victim[L] = i;

while ((∃ k != i level[k] >= L) and victim[L] == i ) {}

}

critical section

level[i] = 0;

Wait as long as someone else is at same or higher level,

and I’m designated victim.

Thread enters level L when it completes the loop.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-43-320.jpg)

![Claim

There are at most n-L threads enter level L

Proof: by induction on L and by contradiction

At L=0 – trivial

Assume that there are at most n-L+1 threads at level

L-1.

Assume that there are n-L+1 threads at level L

Let A be the last thread to write victim[L] and B any

other thread at level L](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-44-320.jpg)

![Proof structure

ncs

cs

Assumed to enter L-1

By way of contradiction

all enter L

n-L+1 = 4

n-L+1 = 4

A B

Last to

write

victim[L]

Show that A must have seen

B at level L and since victim[L] == A

could not have entered](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-45-320.jpg)

![Proof

From the code we get:

From the assumption:

writeB(level[B]=L)writeB(victim[L]=B)

writeA(victim[L]=A)readA(level[B])

writeB(victim[L]=B)writeA(victim[L]=A)

for (int L = 1; L < n; L++) {

level[i] = L;

victim[L] = i;

while ((∃ k != i level[k] >= L) and victim[L] == i ) {}

}

critical section

level[i] = 0;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-46-320.jpg)

![Proof

When combining all we get:

Since B is at level L, when A reads level[B], it

reads a value greater than or equal L and so A

couldn’t completed its loop and still waiting

(remember that victim=A), a contradiction.

writeB(level[B]=L) readA(level[B])

for (int L = 1; L < n; L++) {

level[i] = L;

victim[L] = i;

while ((∃ k != i level[k] >= L) and victim[L] == i ) {}

}

critical section

level[i] = 0;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-47-320.jpg)

![Bakery Algorithm

Thread i

flag[i]=true;

number[i] = max(number[0], …,number[n-1])+1;

while (∃ k!= i

flag[k] && (number[i],i) > (number[k],k)) {};

critical section

flag[i] = false;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-56-320.jpg)

![Bakery Algorithm

flag[i]=true;

number[i] = max(number[0], …,number[n-1])+1;

while (∃ k!= i

flag[k] && (number[i],i) > (number[k],k)) {};

critical section

flag[i] = false;

Doorway](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-57-320.jpg)

![Bakery Algorithm

flag[i]=true;

number[i] = max(number[0], …,number[n-1])+1;

while (∃ k!= i

flag[k] && (number[i],i) > (number[k],k)) {};

critical section

flag[i] = false;

I’m interested](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-58-320.jpg)

![Bakery Algorithm

flag[i]=true;

number[i] = max(number[0], …,number[n-1])+1;

while (∃ k!= i

flag[k] && (number[i],i) > (number[k],k)) {};

critical section

flag[i] = false;

Take an number

numbers are always increasing!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-59-320.jpg)

![Bakery Algorithm

flag[i]=true;

number[i] = max(number[0], …,number[n-1])+1;

while (∃ k!= i

flag[k] && (number[i],i) > (number[k],k)) {};

critical section

flag[i] = false;

Someone is interested](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-60-320.jpg)

![Bakery Algorithm

flag[i]=true;

number[i] = max(number[0], …,number[n-1])+1;

while (∃ k!= i

flag[k] && (number[i],i) > (number[k],k)) {};

critical section

flag[i] = false;

There is someone with a lower

number and identifier.

pair (a,b) > (c,d) if a>c, or a=c and b>d

(lexicographic order)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-61-320.jpg)

![Deadlock freedom

The bakery algorithm is deadlock free

Some waiting thread A has a unique least

(number[A],A) pair, and that thread can enter

the critical section](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-62-320.jpg)

![FIFO

The bakery algorithm is first-come-first-

served

If DA DB then A’s number is earlier

– writeA(number[A]) readB(number[A])

writeB(number[B]) readB(flag[A])

So B is locked out while flag[A] is true

flag[i]=true;

number[i] = max(number[0], …,number[n-1])+1;

while (∃ k!= i

flag[k] && (number[i],i) > (number[k],k)) {};

critical section

flag[i] = false;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-63-320.jpg)

![Mutual Exclusion

Suppose A and B in CS together

Suppose A has an earlier number

When B entered, it must have seen

– flag[A] is false, or

– number[A] > number[B]

flag[i]=true;

number[i] = max(number[0], …,number[n-1])+1;

while (∃ k!= i

flag[k] && (number[i],i) > (number[k],k)) {};

critical section

flag[i] = false;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-65-320.jpg)

![Mutual Exclusion

numbers are strictly increasing so

B must have seen (flag[A] == false)

numberingB readB(flag[A]) writeA(flag[A])

numberingA

Which contradicts the assumption that A has

an earlier number

flag[i]=true;

number[i] = max(number[0], …,number[n-1])+1;

while (∃ k!= i

flag[k] && (number[i],i) > (number[k],k)) {};

critical section

flag[i] = false;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutualexclusion-140822113340-phpapp02/85/Mutual-exclusion-66-320.jpg)