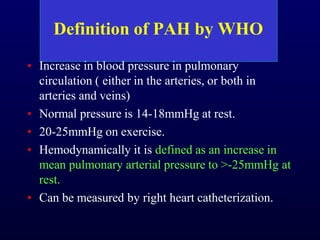

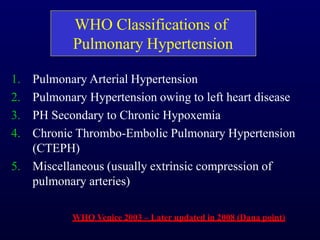

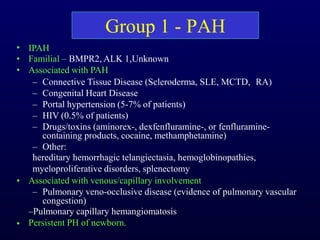

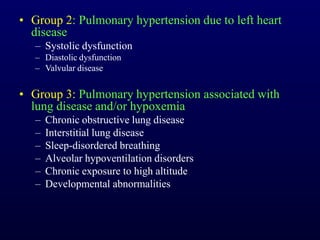

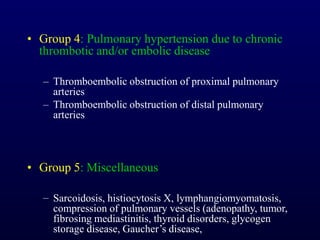

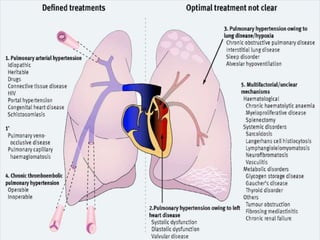

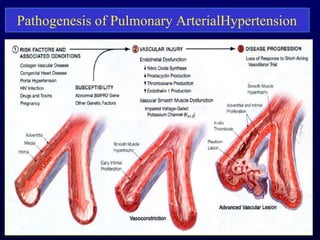

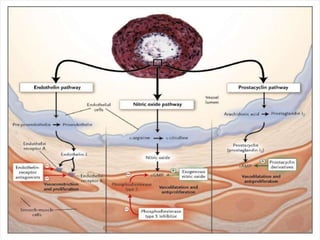

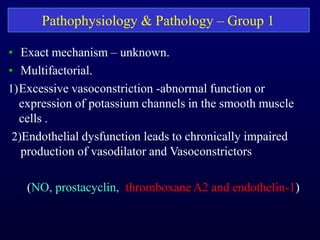

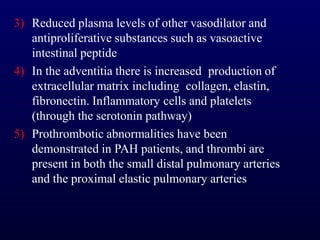

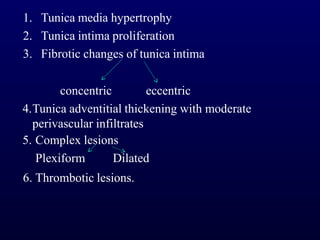

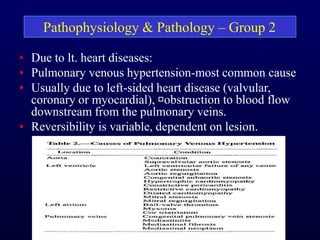

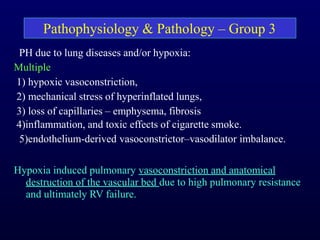

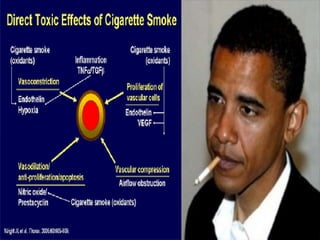

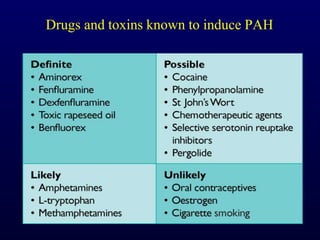

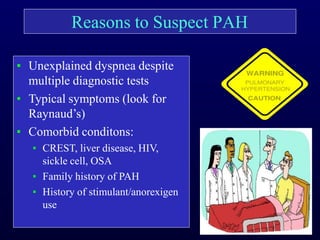

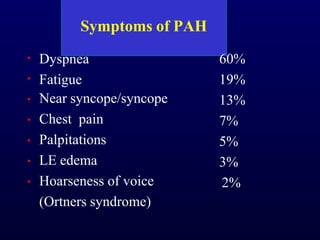

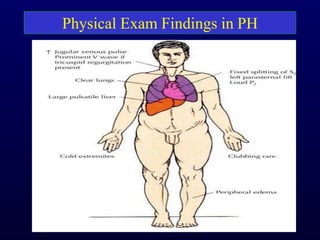

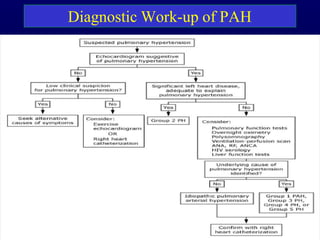

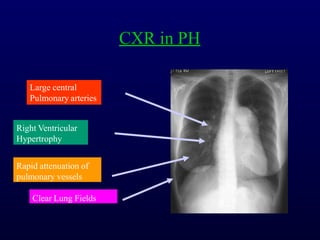

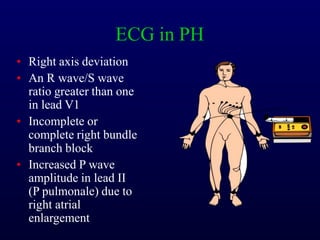

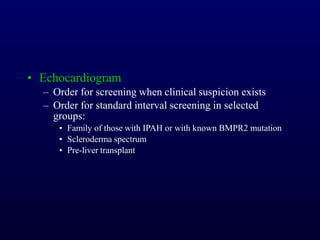

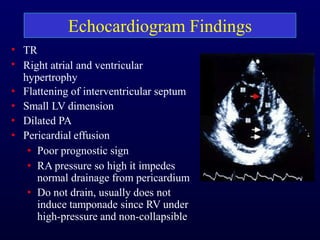

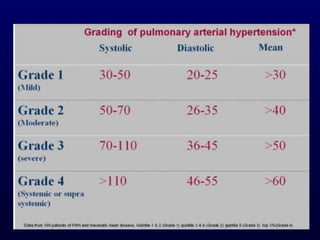

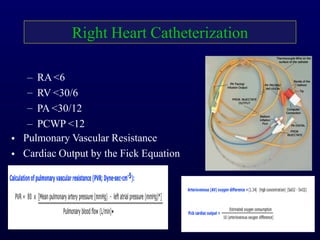

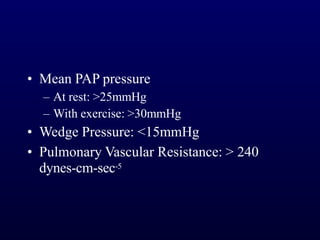

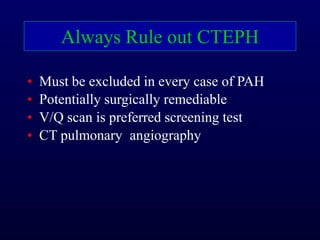

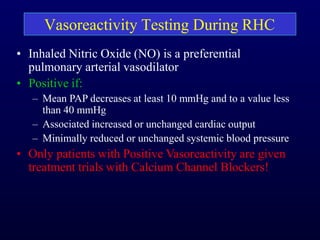

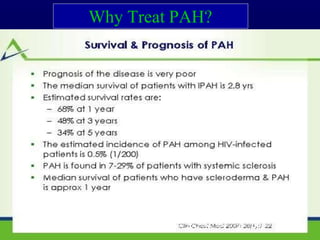

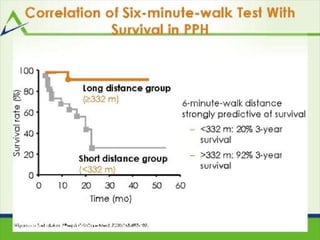

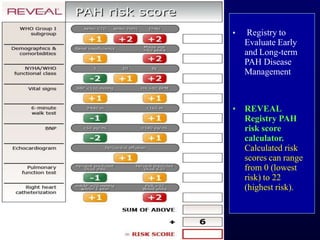

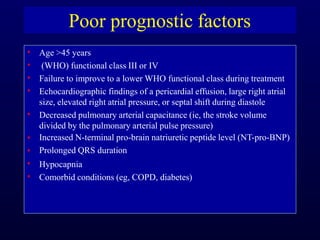

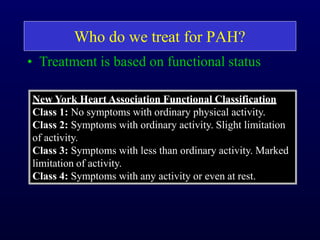

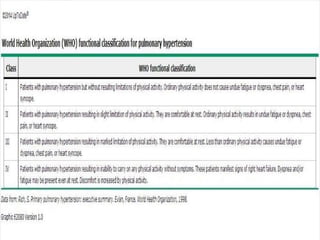

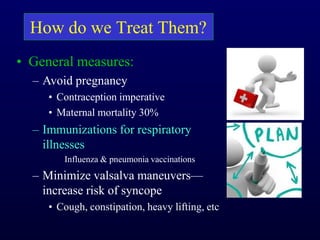

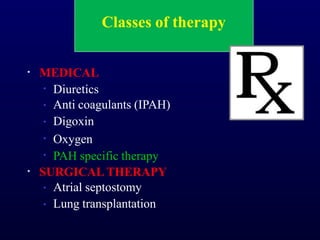

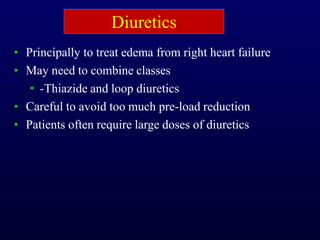

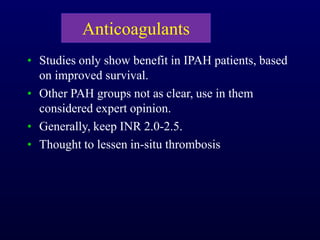

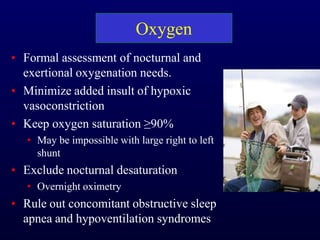

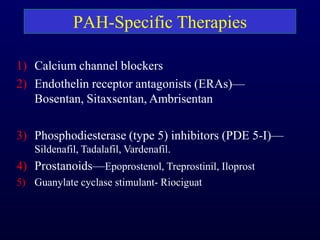

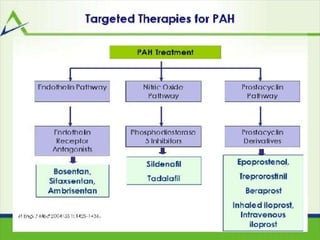

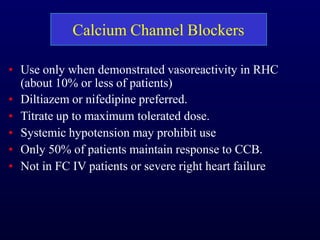

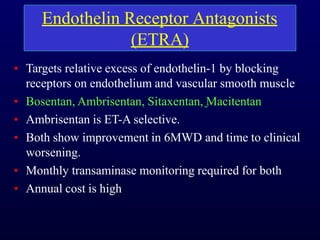

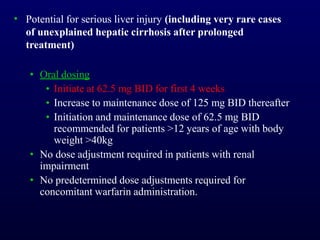

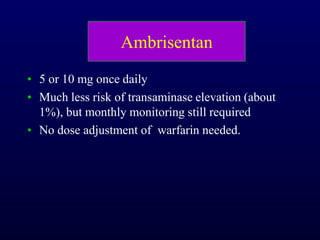

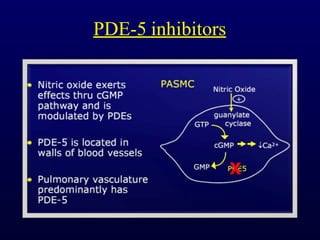

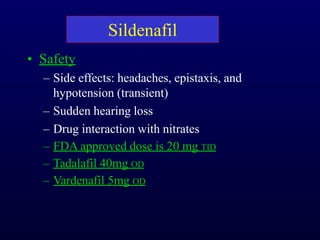

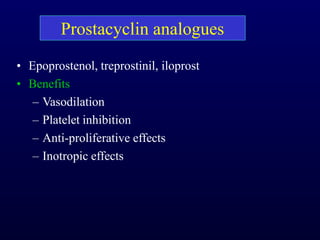

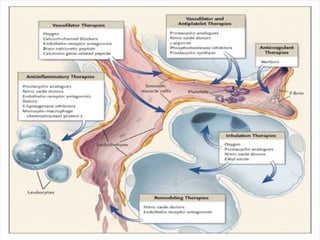

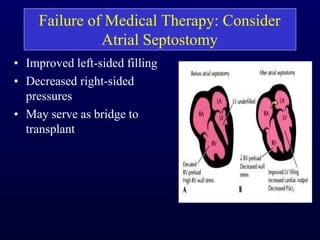

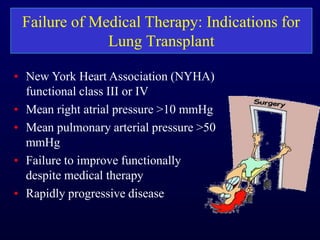

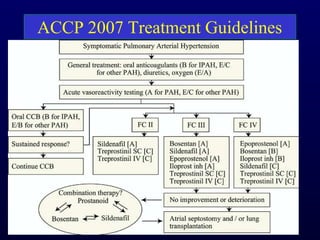

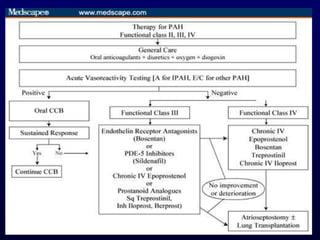

This document provides an overview of pulmonary hypertension (PH), including its definition, classification, pathophysiology, diagnostic workup, and treatment. PH is defined as a mean pulmonary arterial pressure over 25 mmHg at rest. It is classified into 5 groups, with Group 1 being pulmonary arterial hypertension. The pathophysiology involves vasoconstriction, endothelial dysfunction, and vascular remodeling. Diagnosis involves echocardiogram, right heart catheterization, and ruling out other causes. Treatment includes diuretics, anticoagulants, oxygen, and PAH-specific therapies, with the goal of improving functional status and survival.