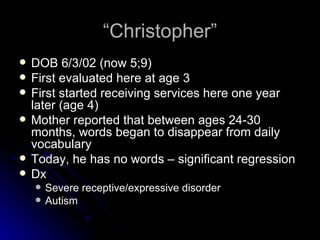

The document discusses interventions for nonverbal children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). It describes three main approaches: the behavioral approach, naturalistic behavioral approach, and developmental social-pragmatic approach. It then discusses a case study of a 5-year-old nonverbal boy named Christopher and his lack of progress using a naturalistic behavioral intervention. The take home message is that there is no single intervention approach that works for all children with ASD, and an intervention needs to be carefully selected based on the child's individual strengths, weaknesses, and characteristics.