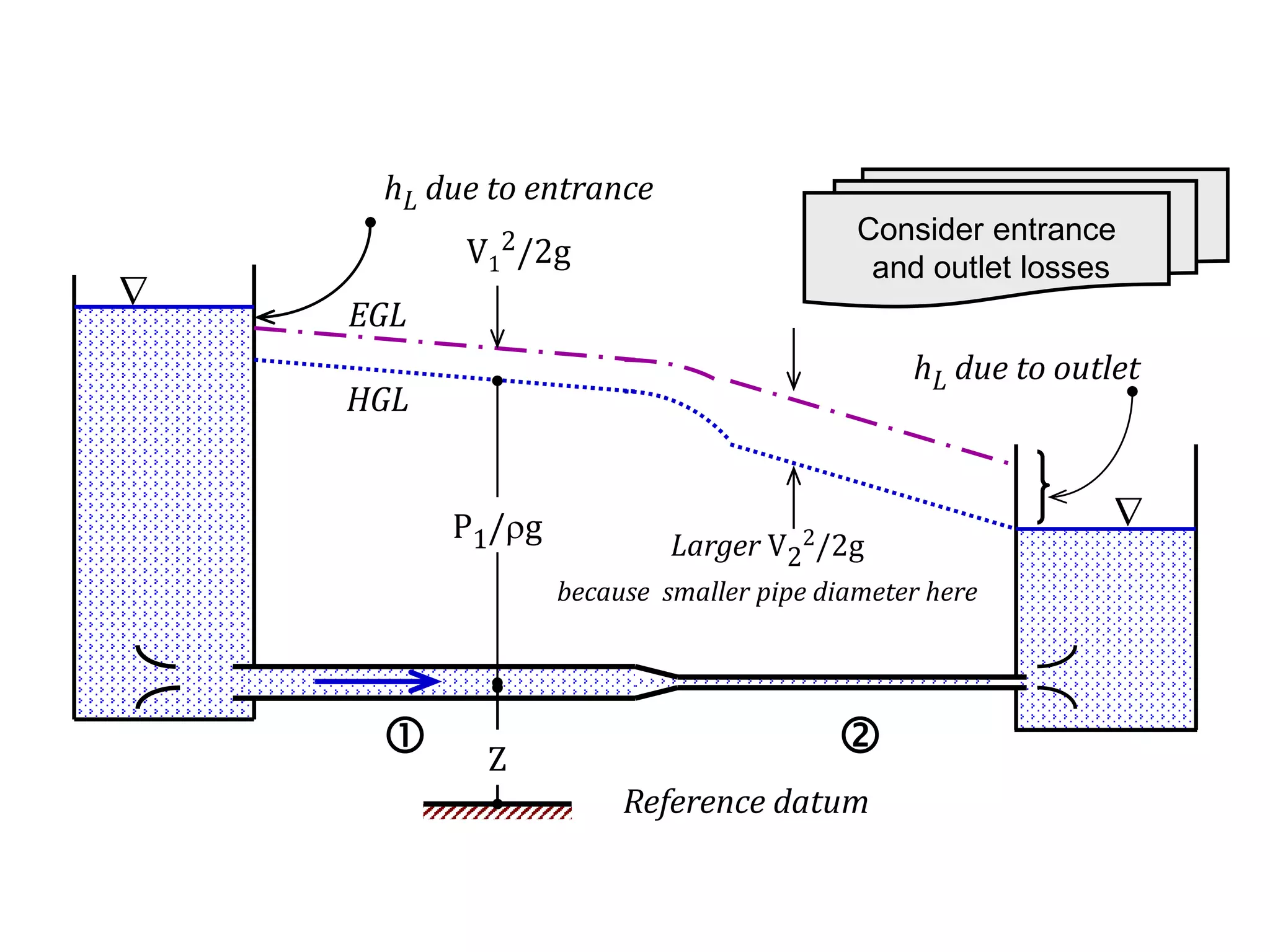

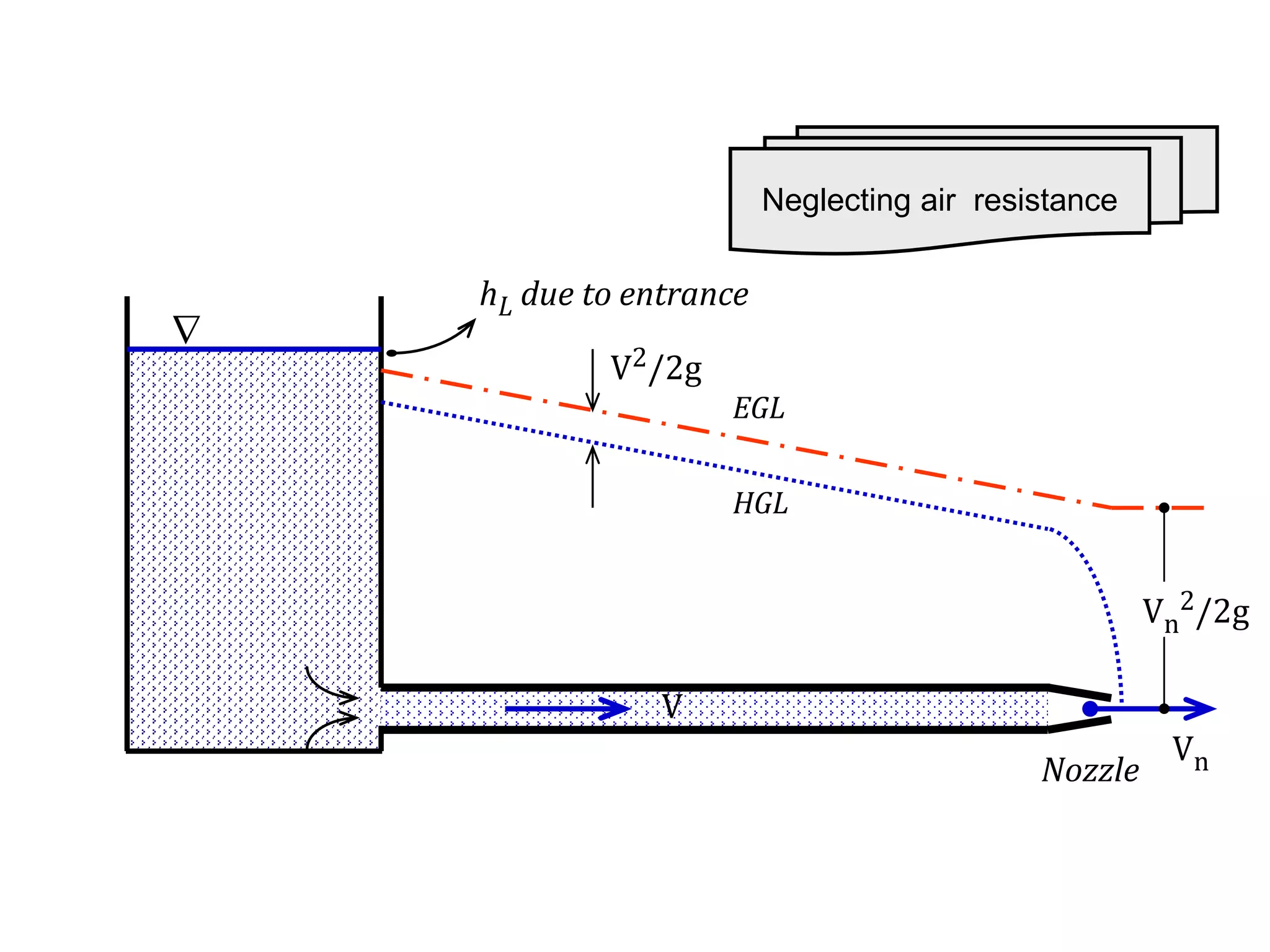

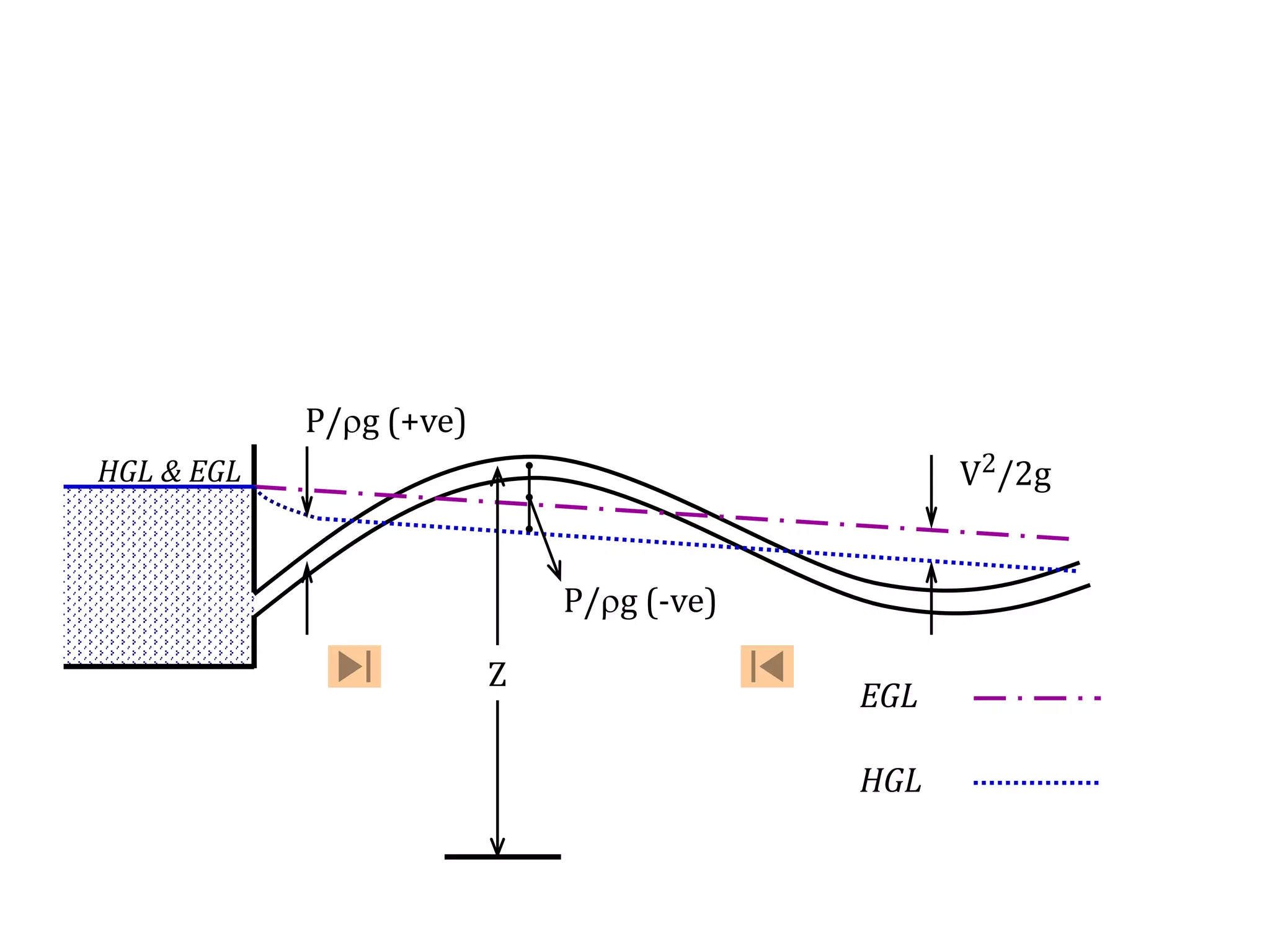

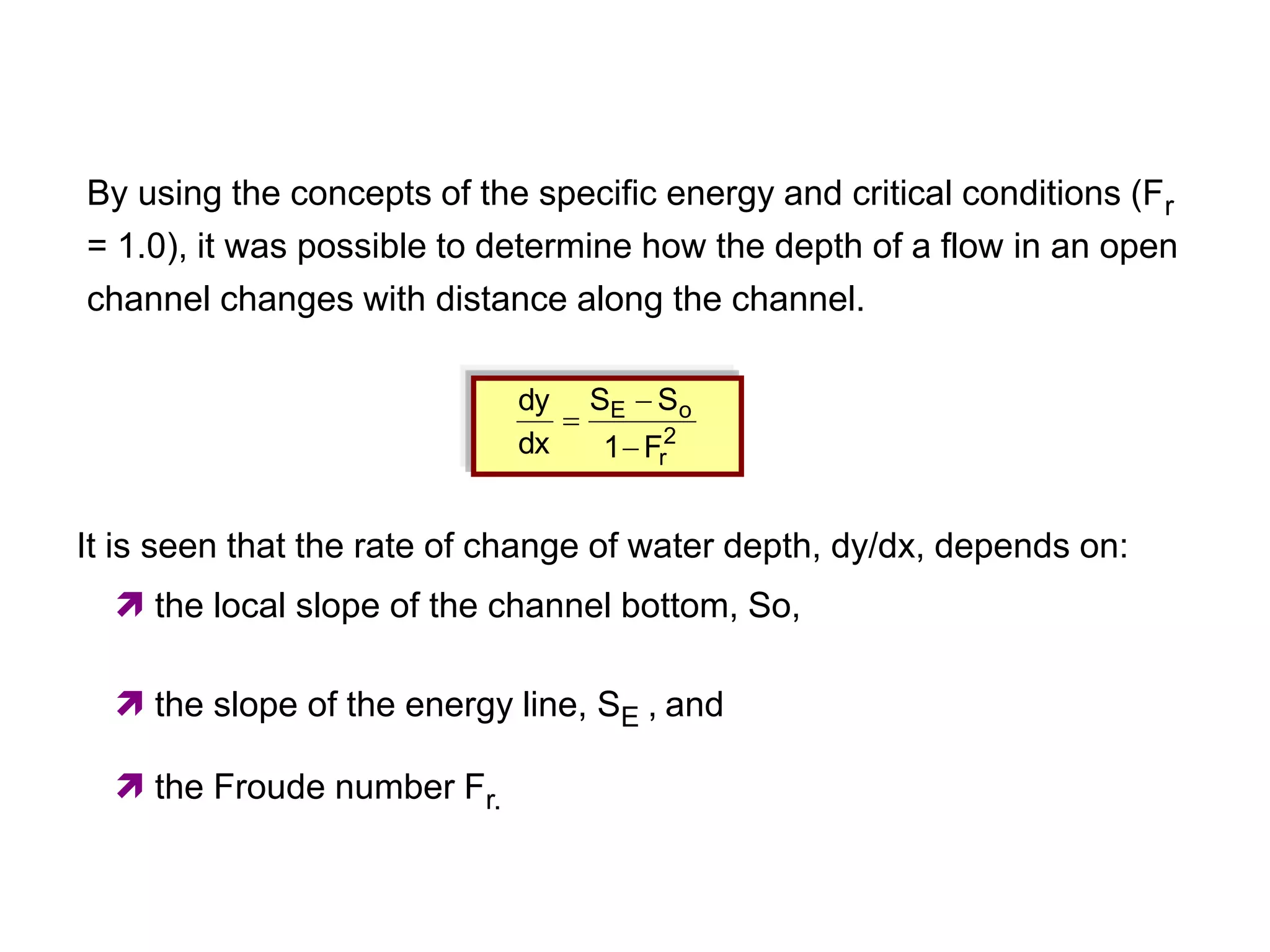

This document contains diagrams and equations related to fluid mechanics concepts such as:

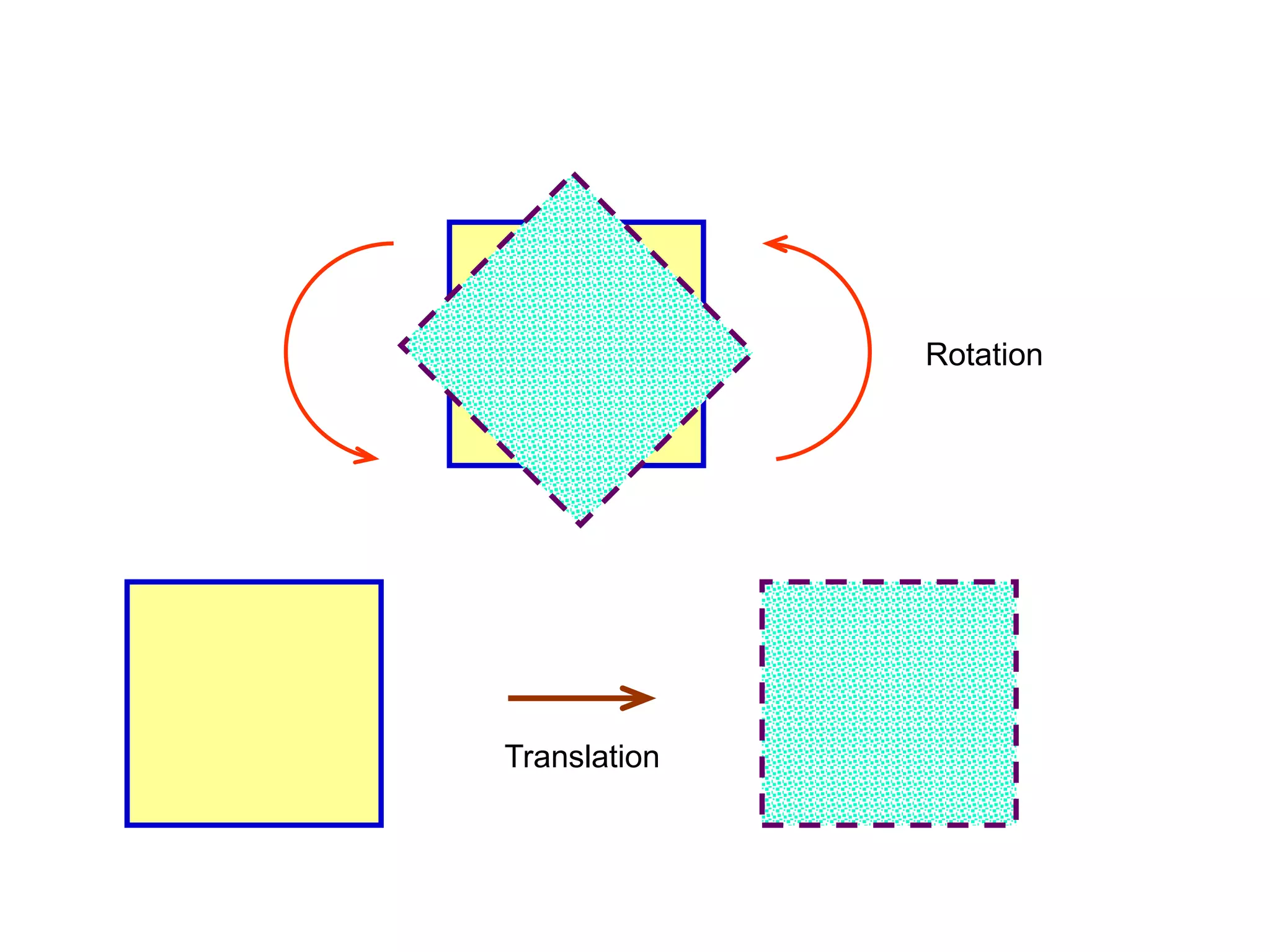

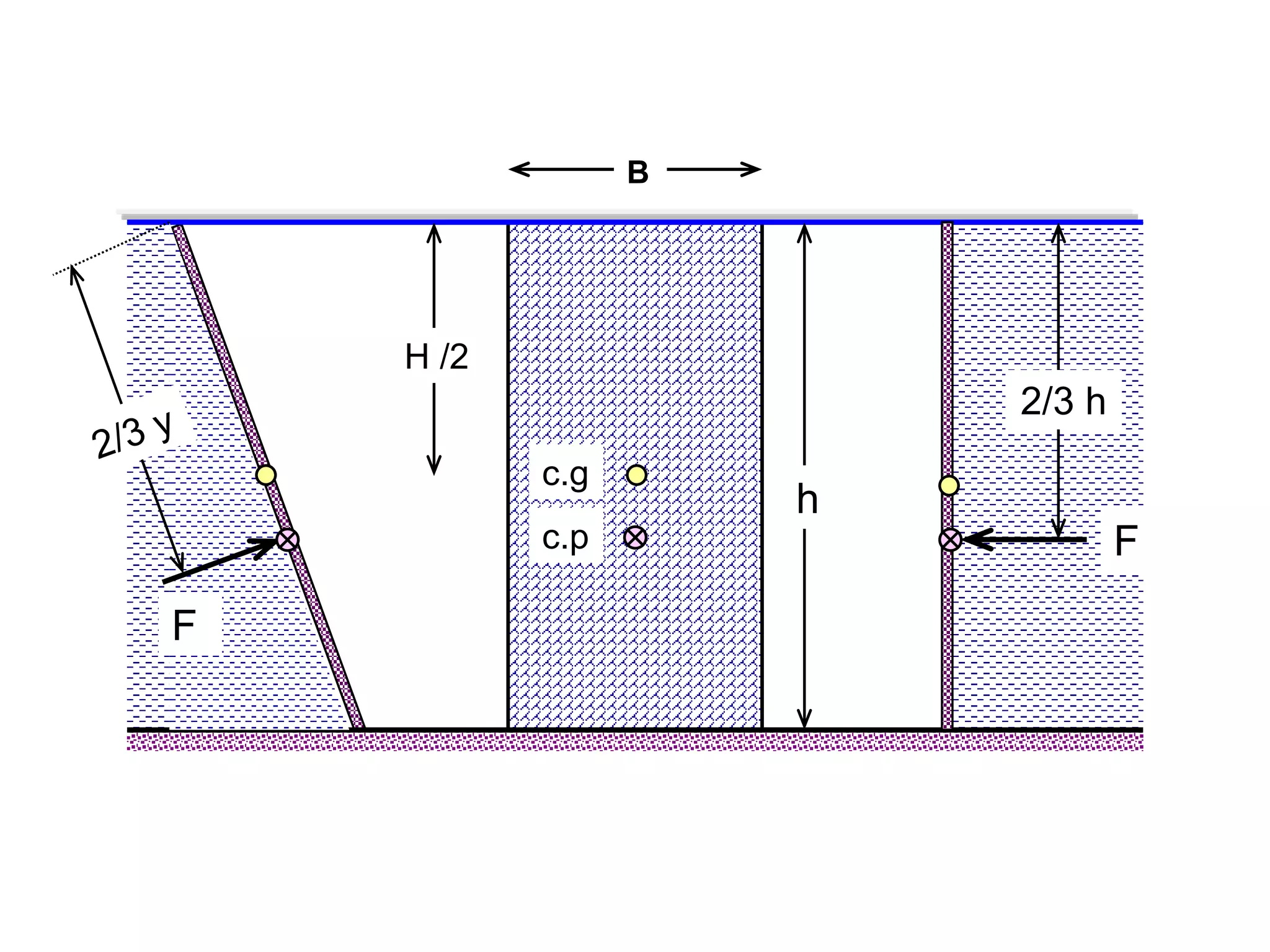

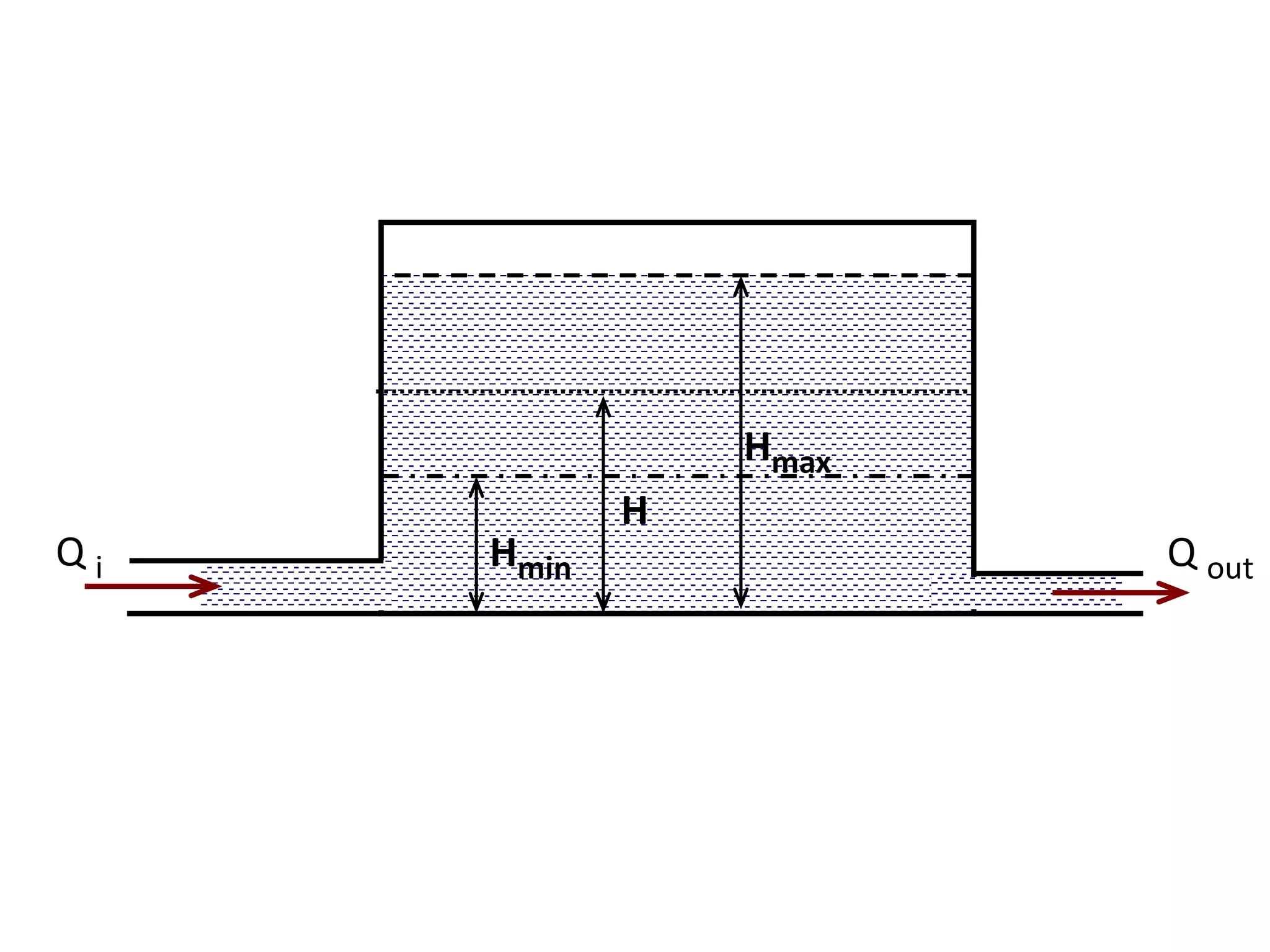

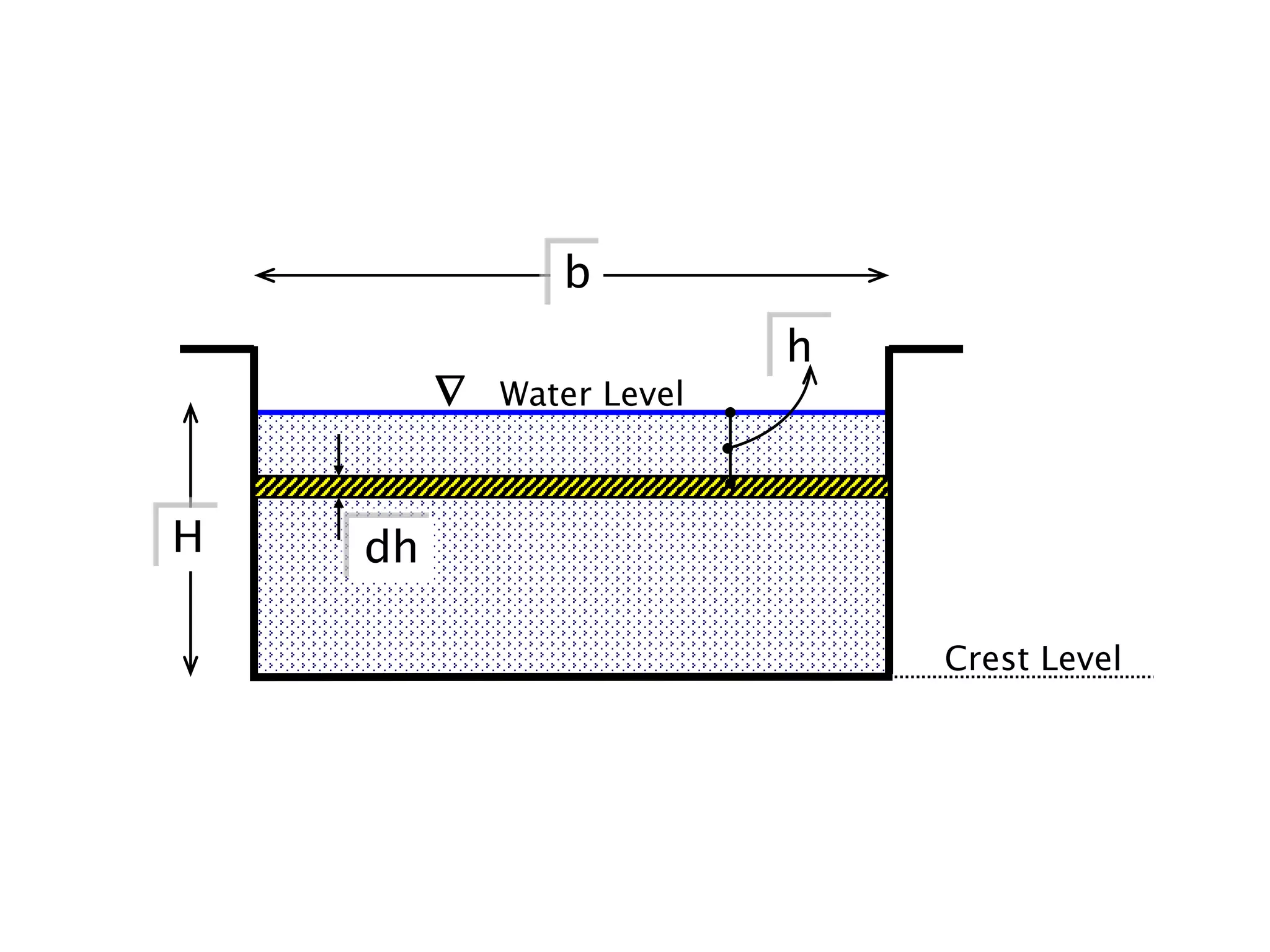

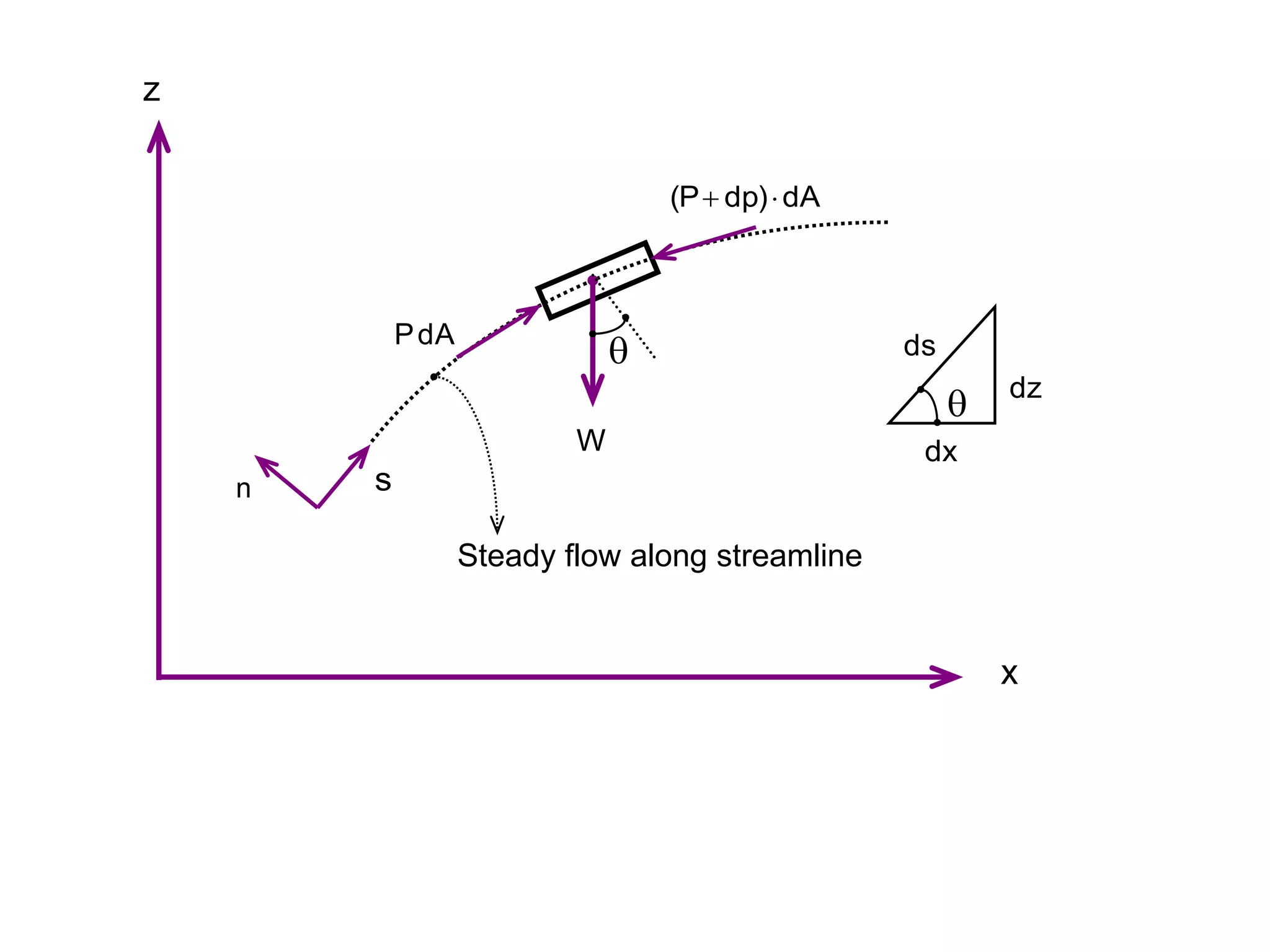

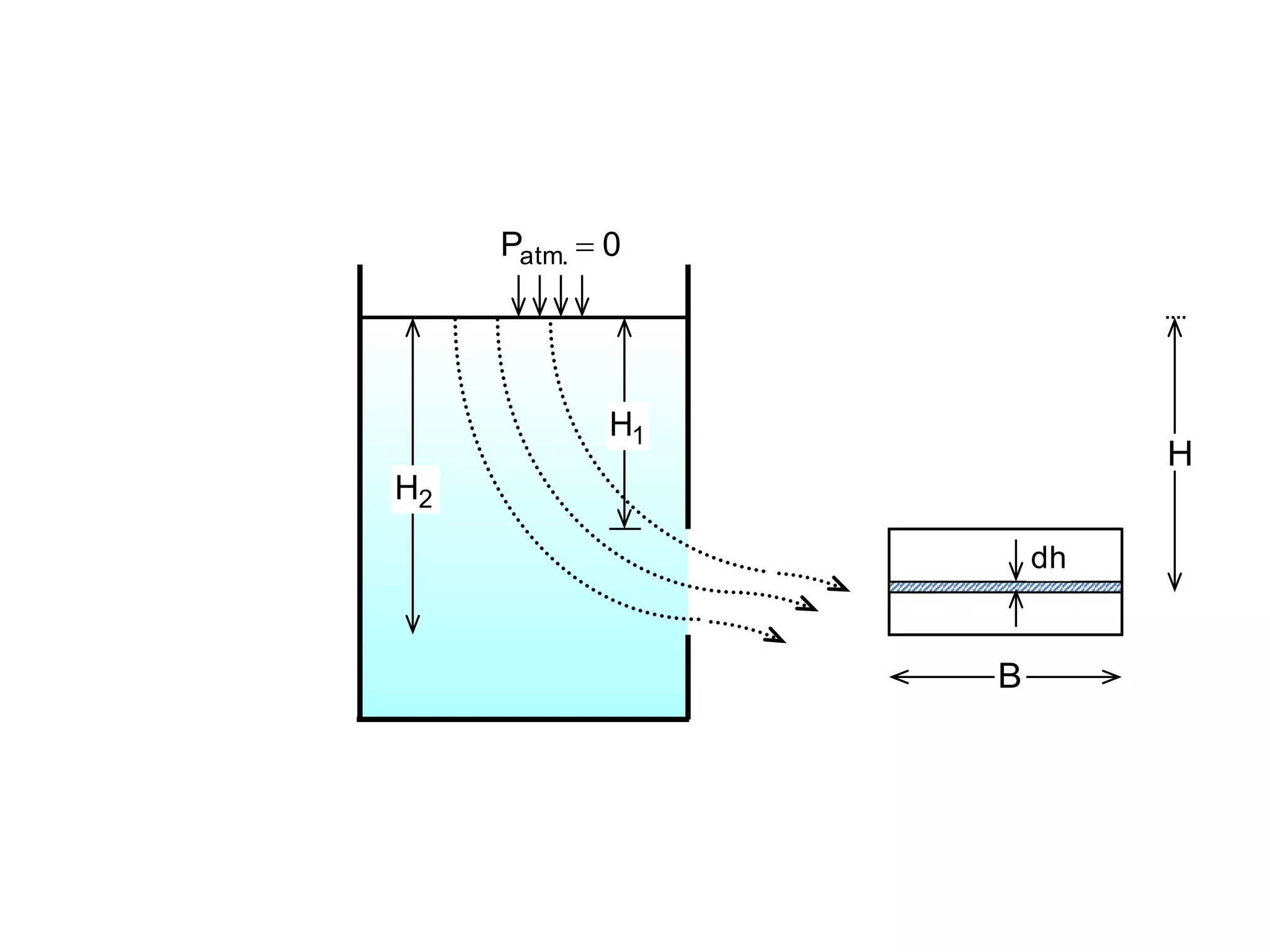

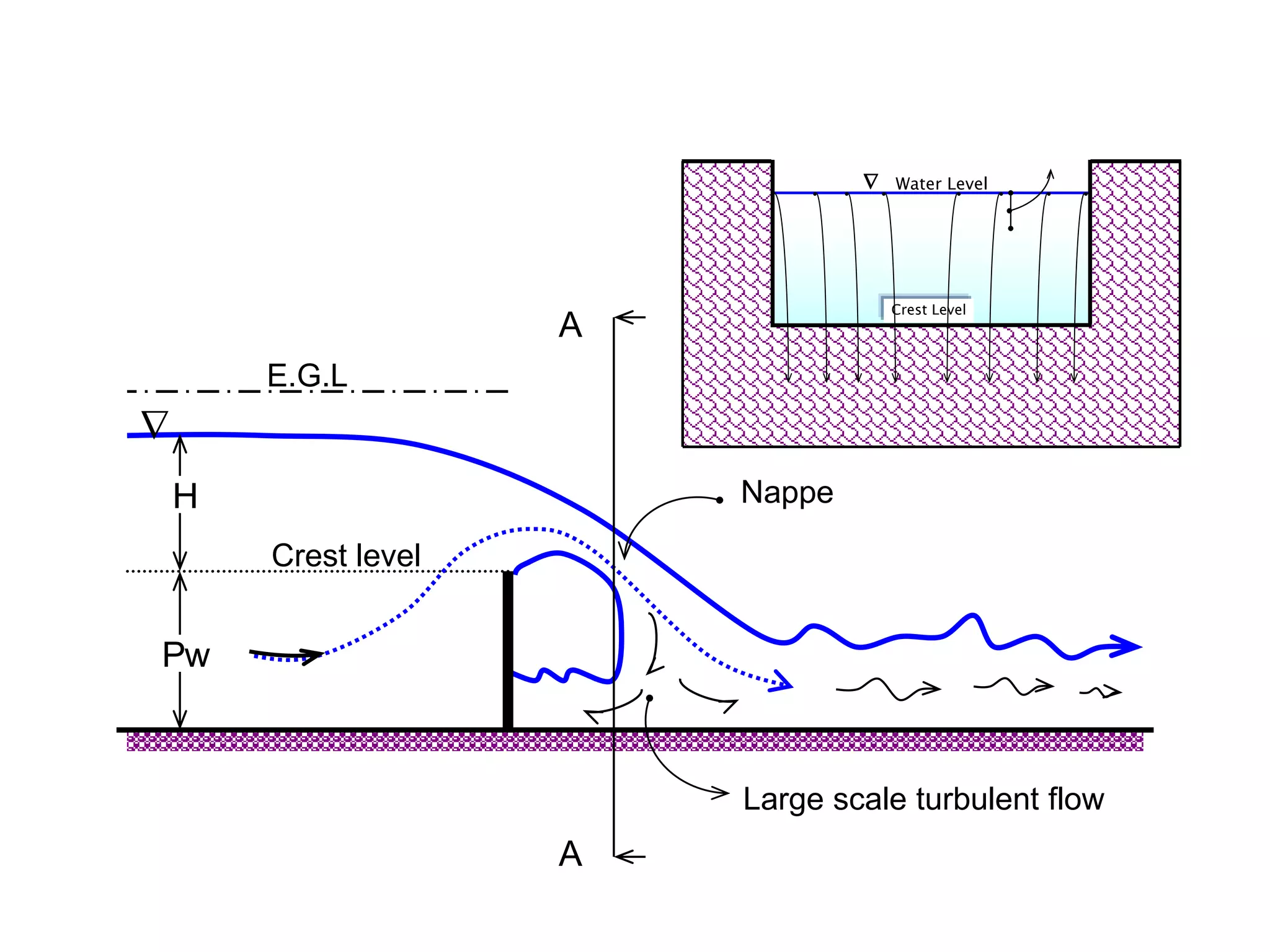

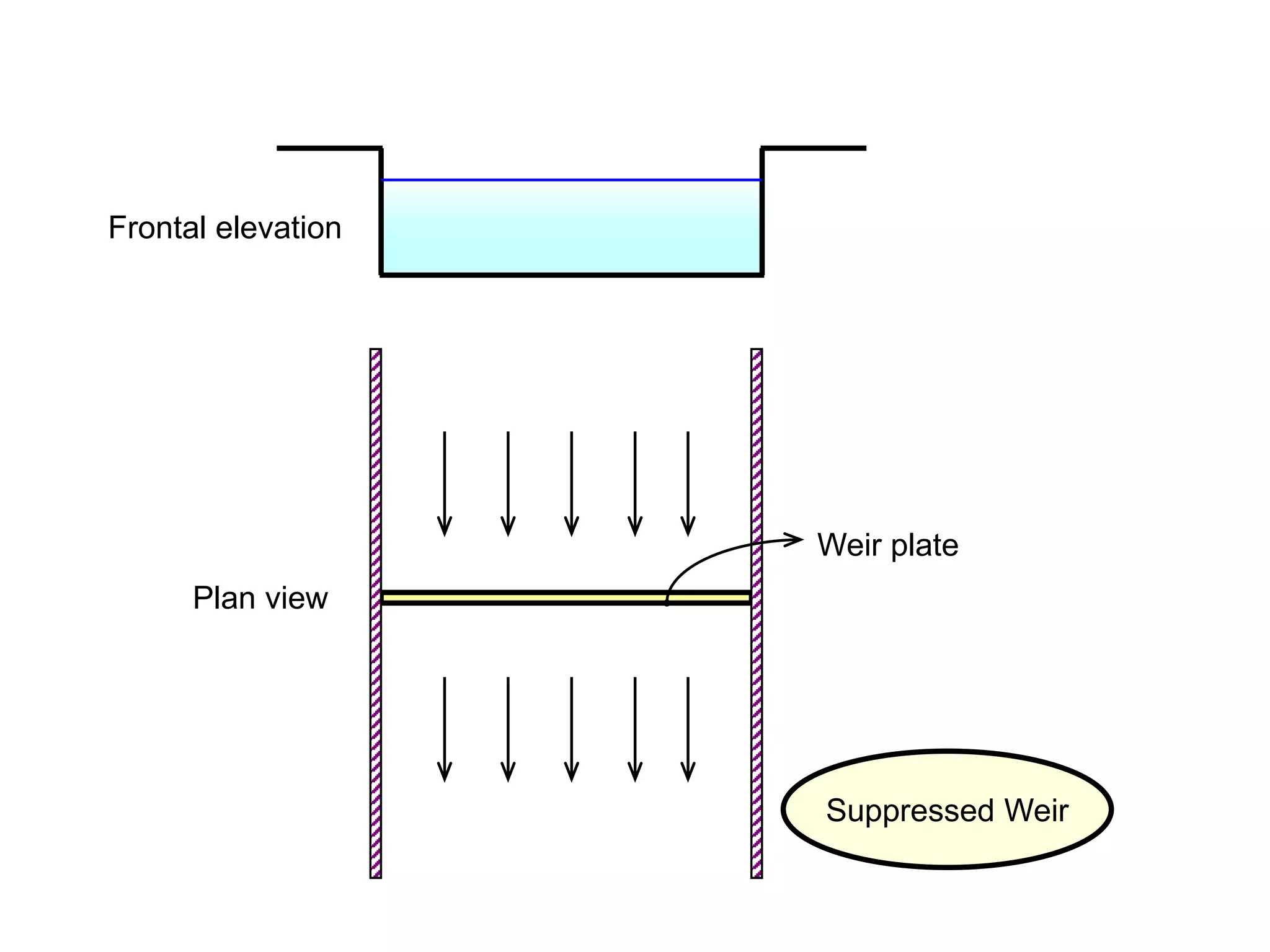

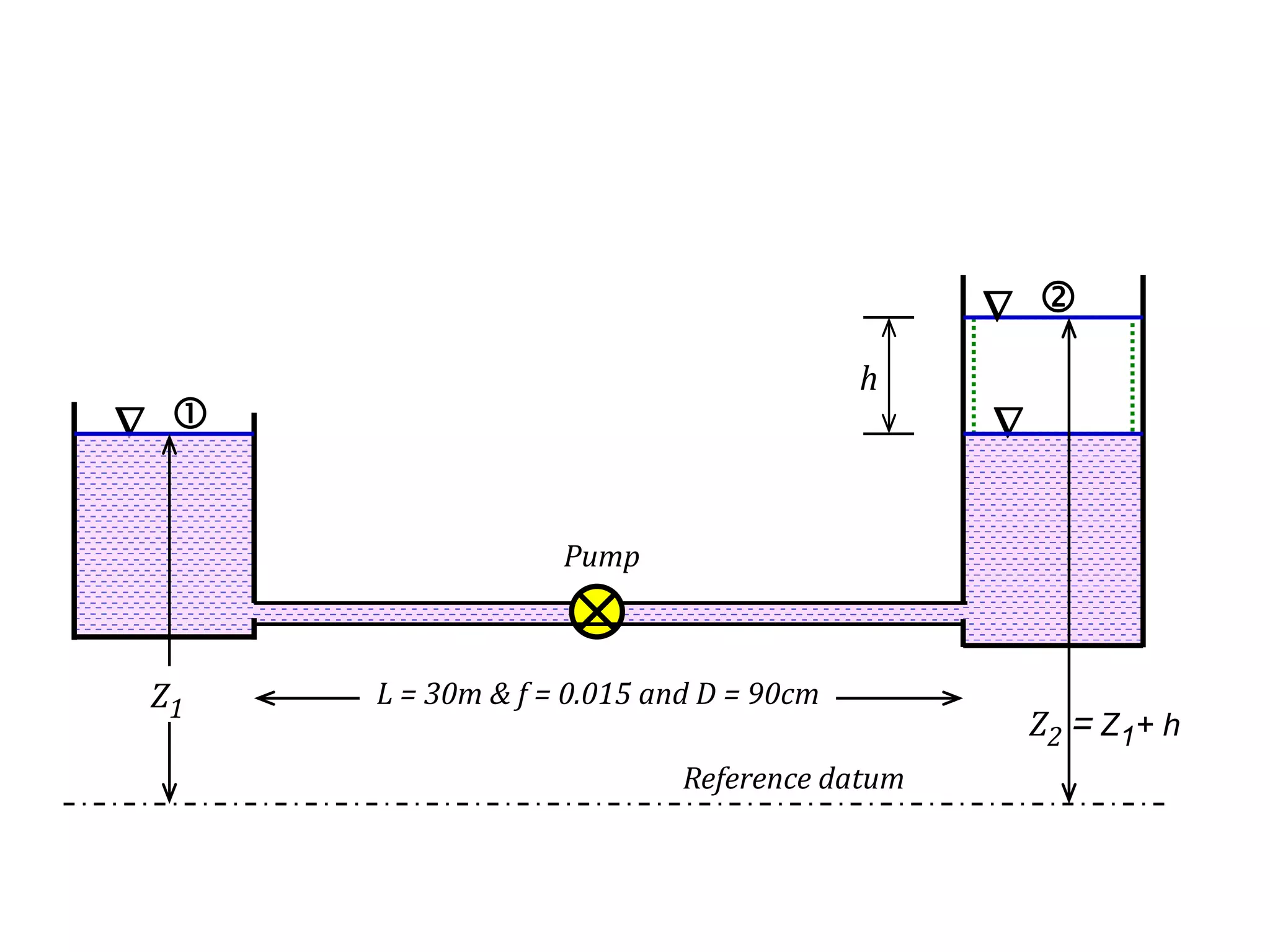

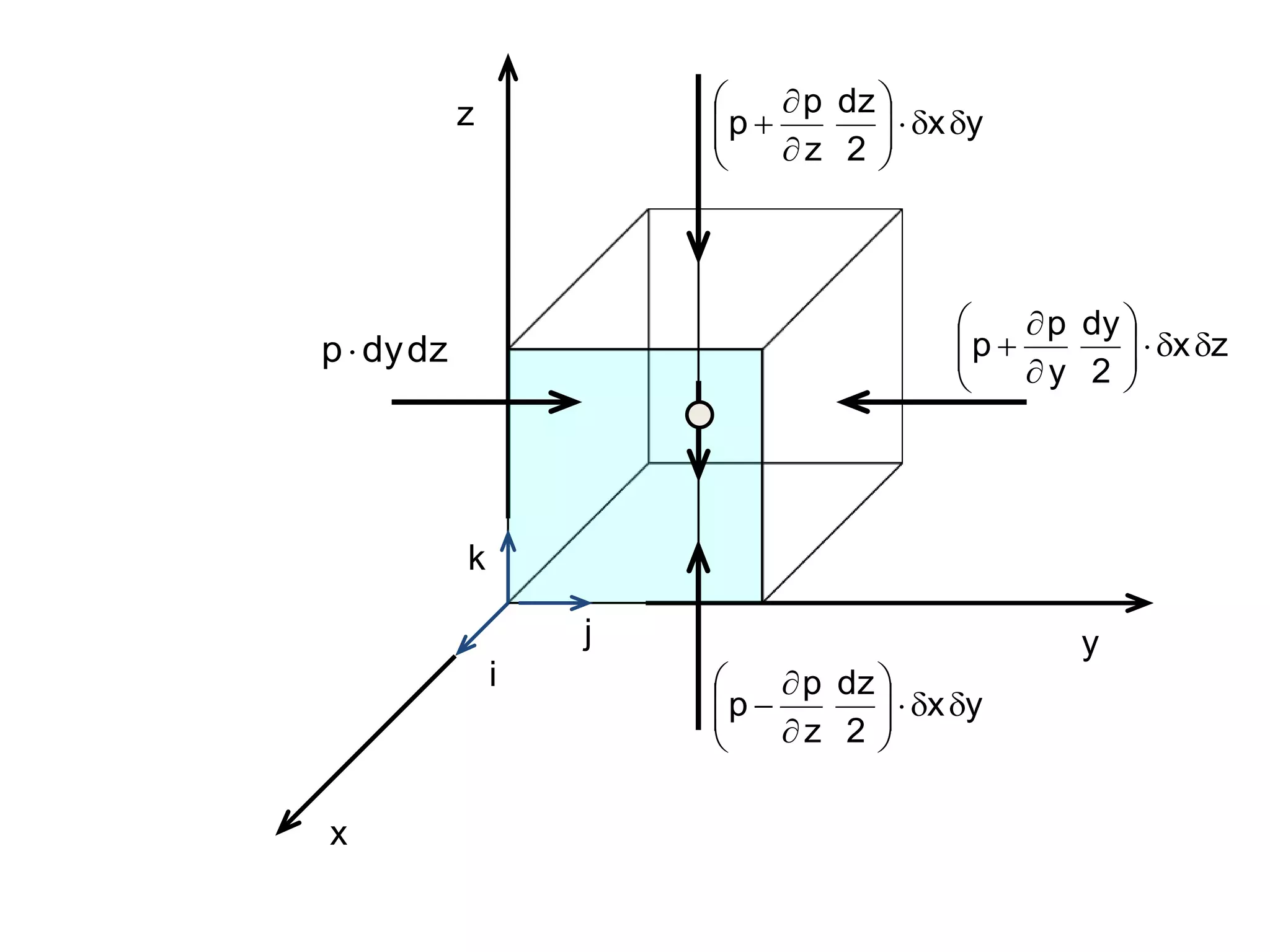

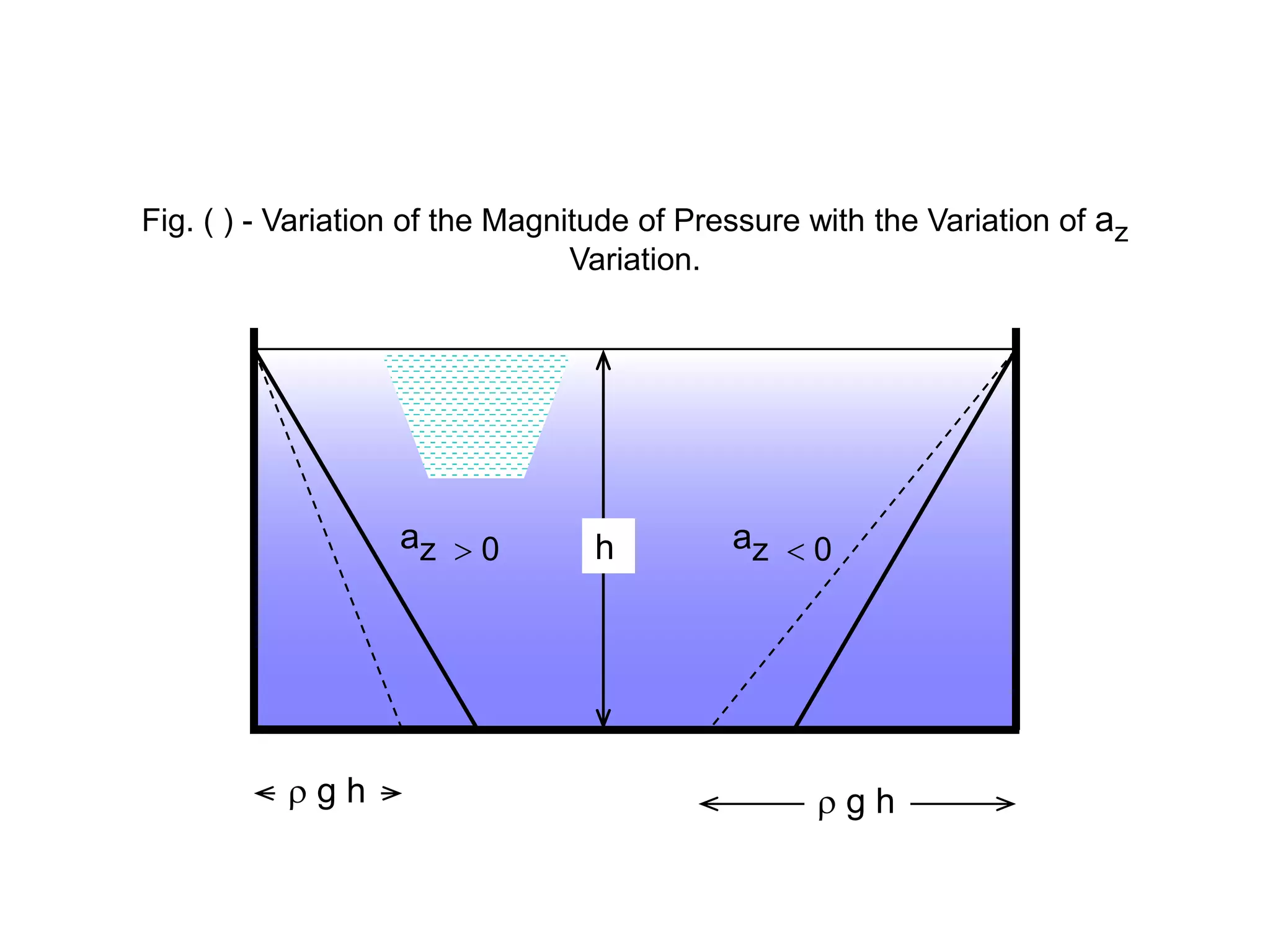

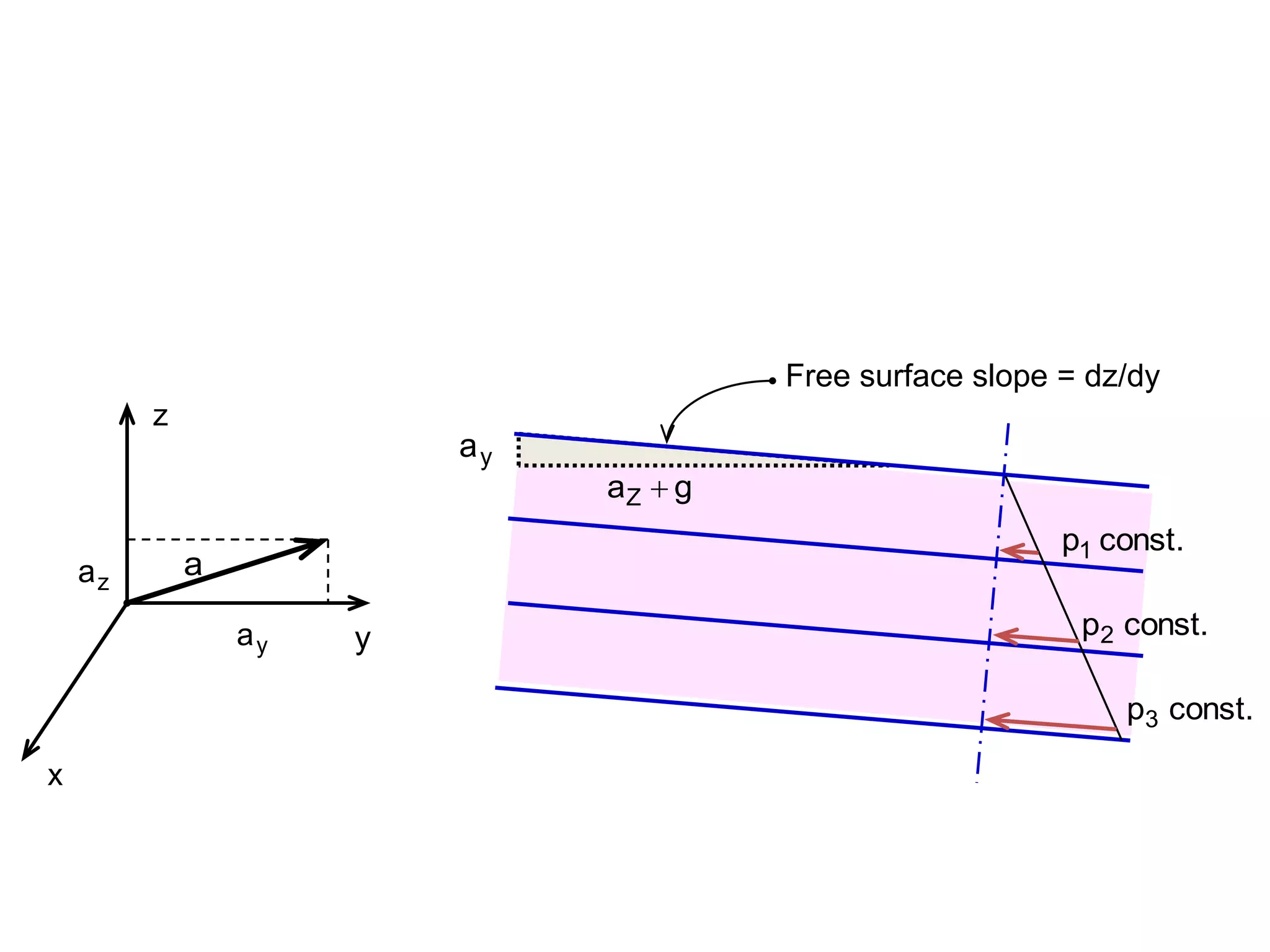

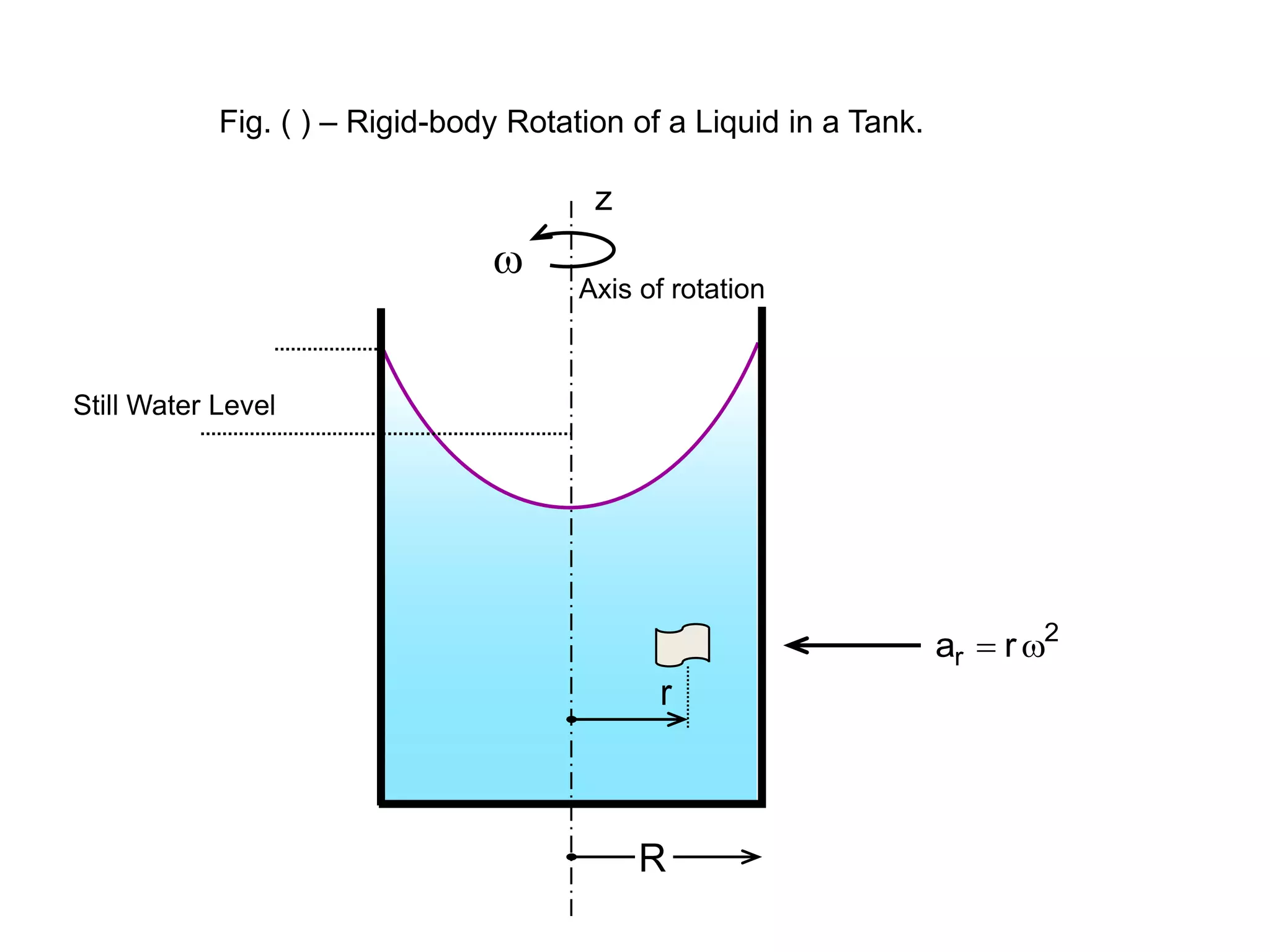

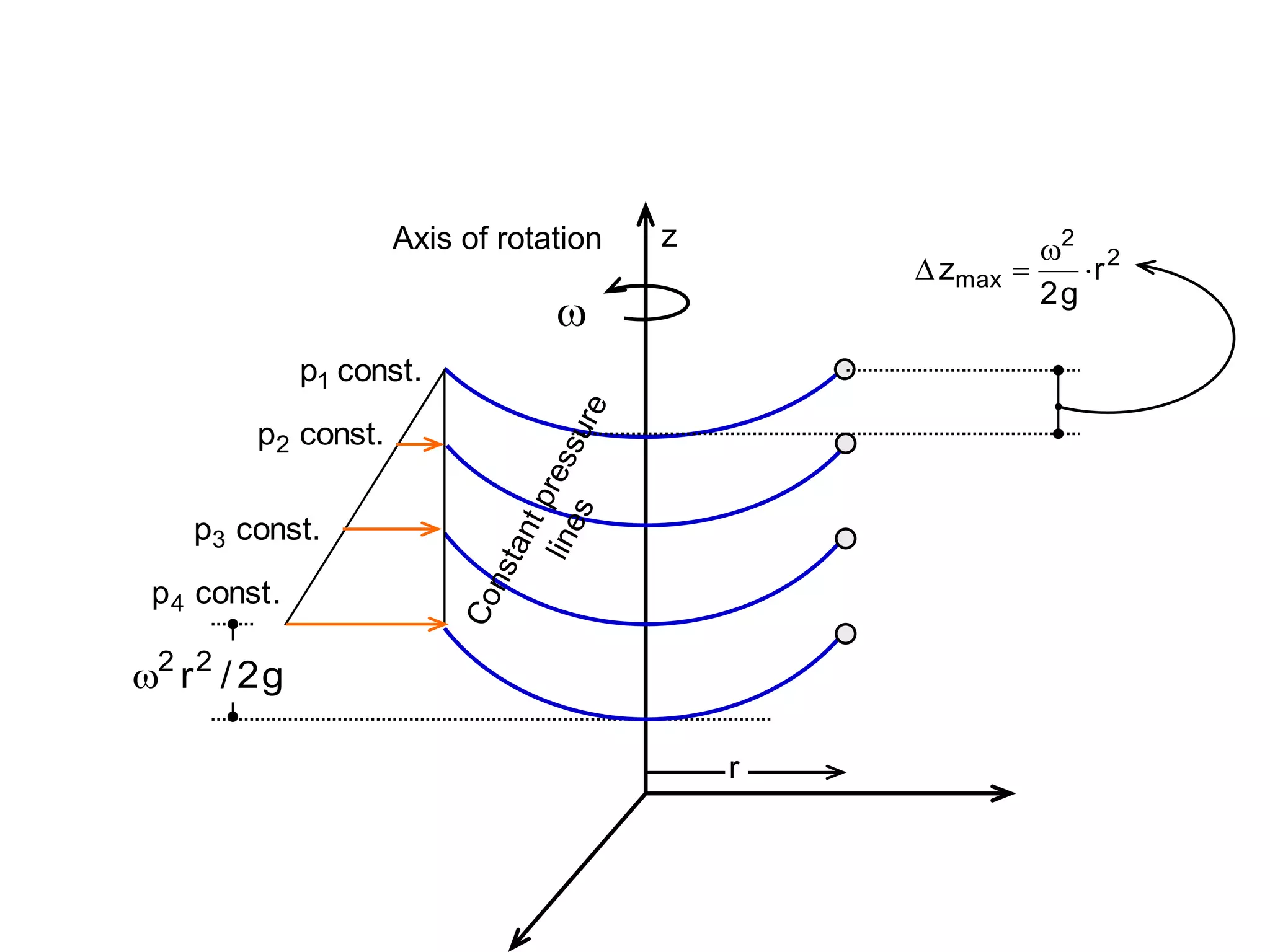

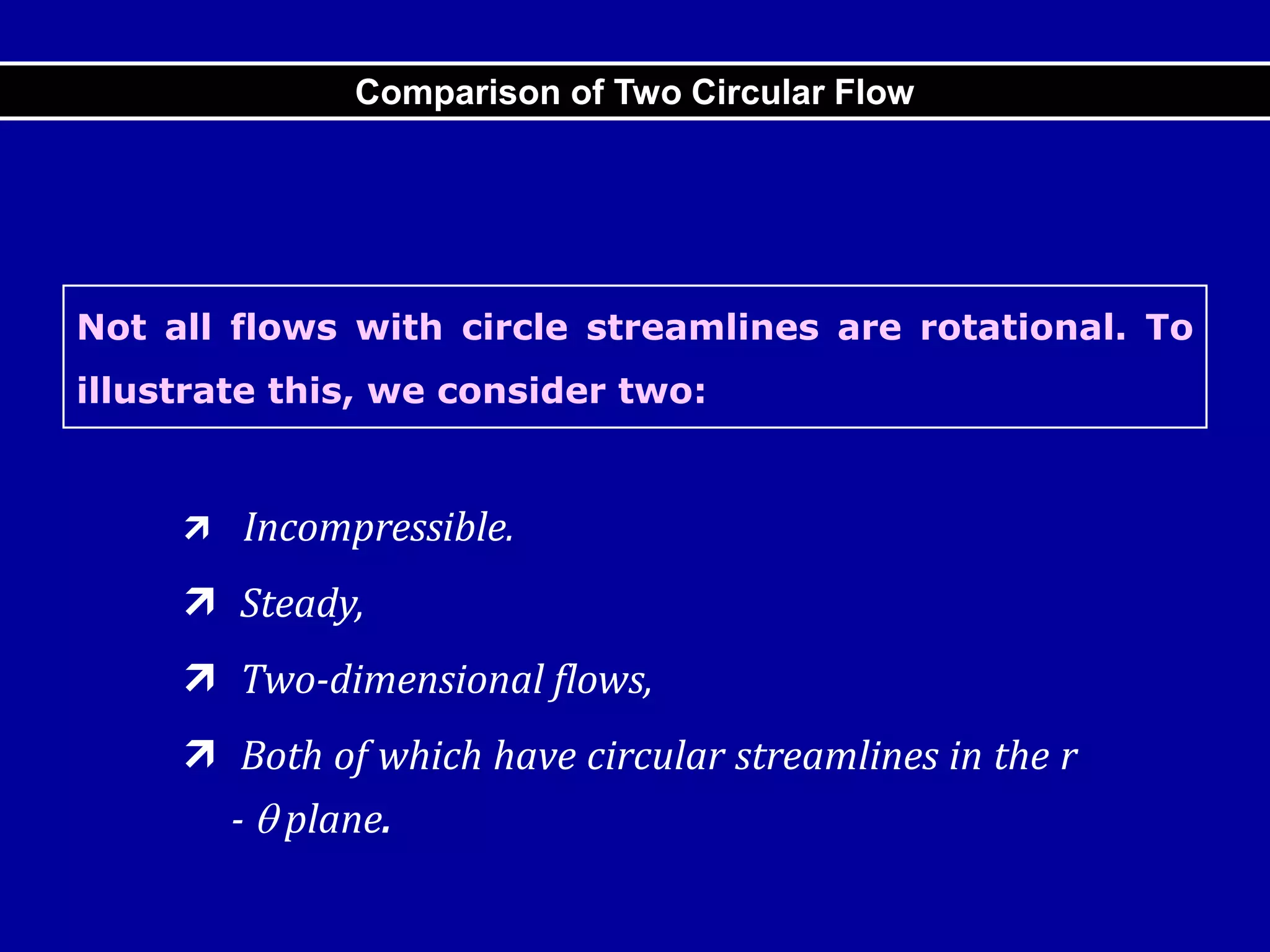

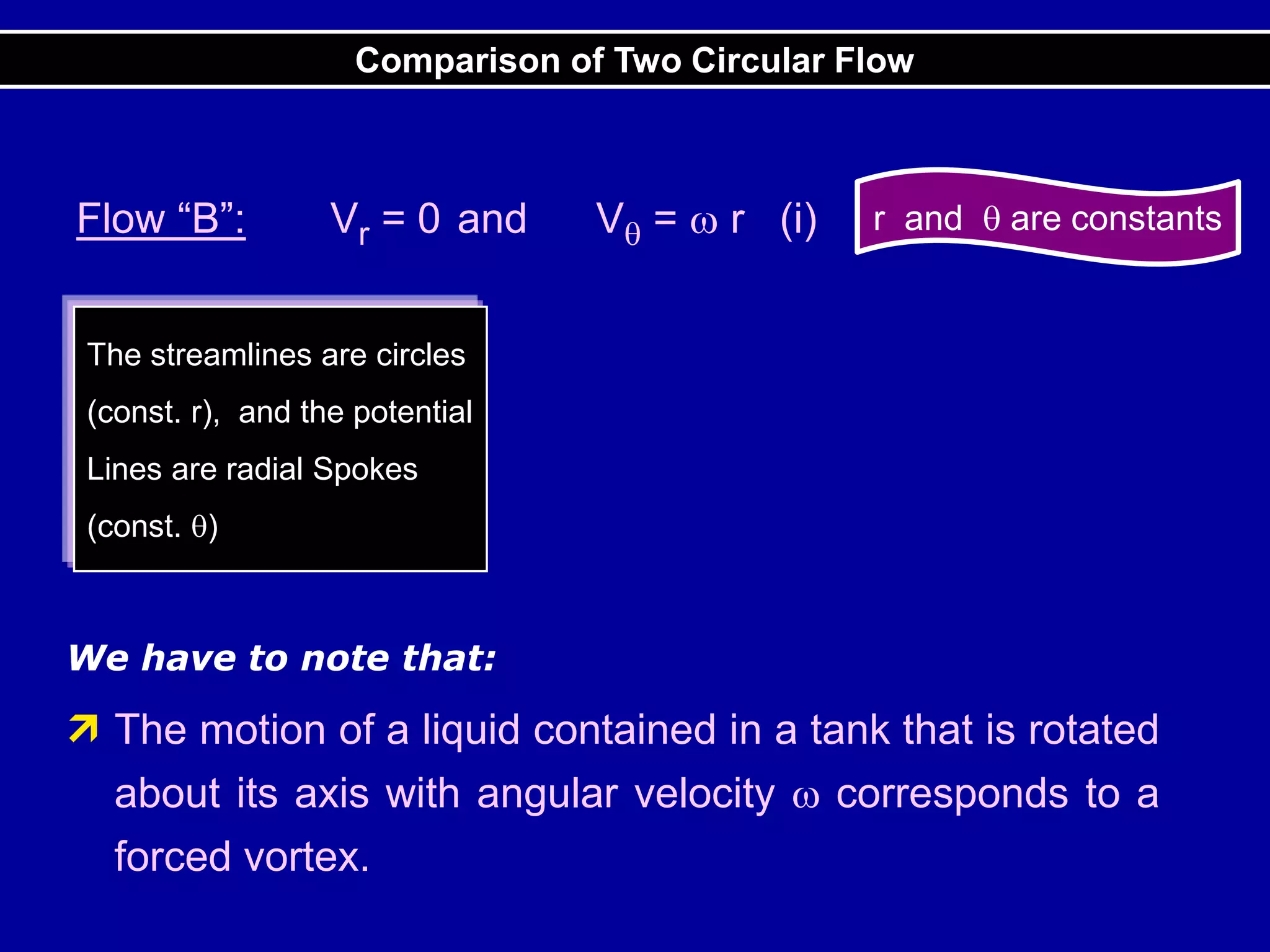

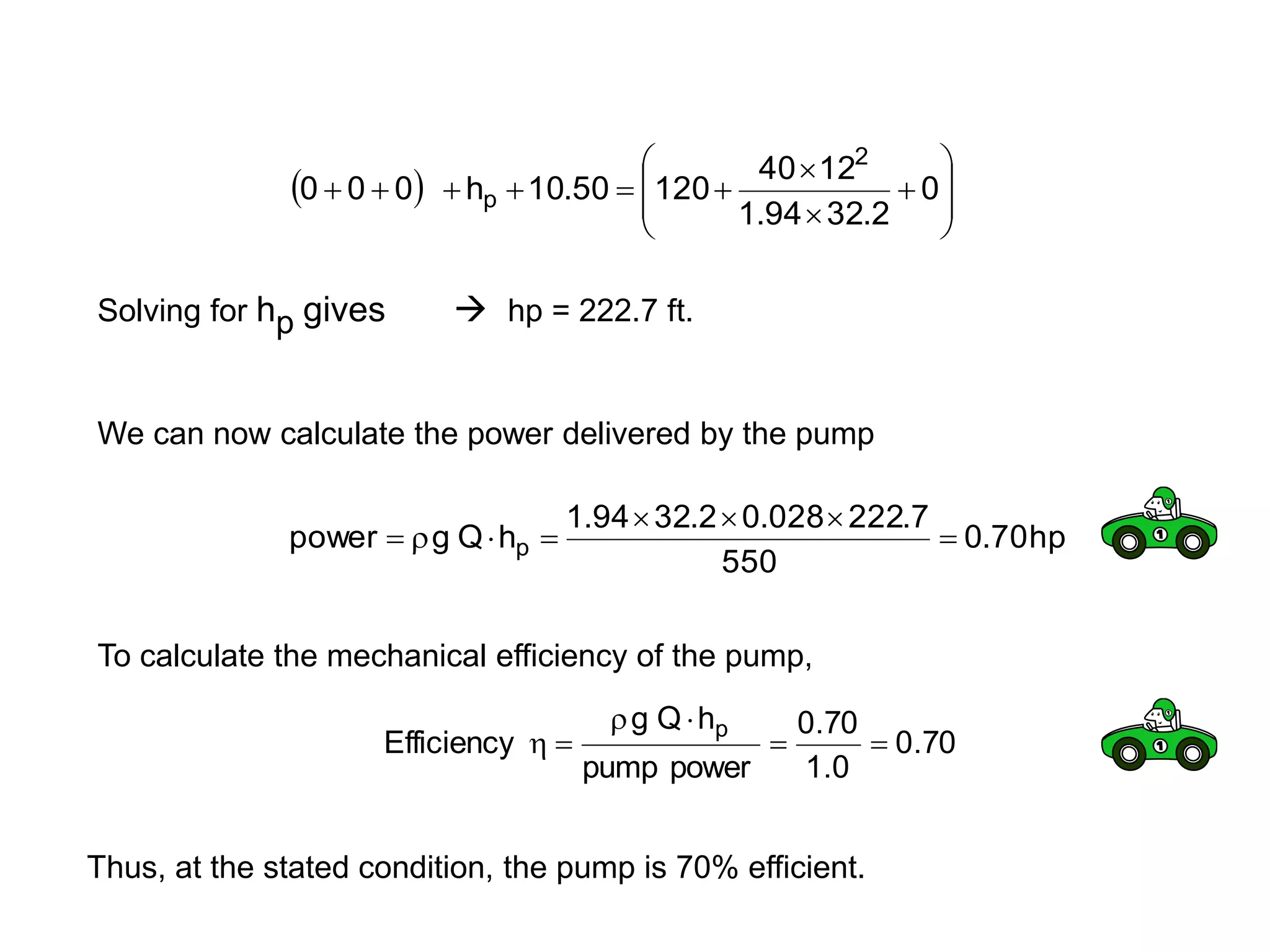

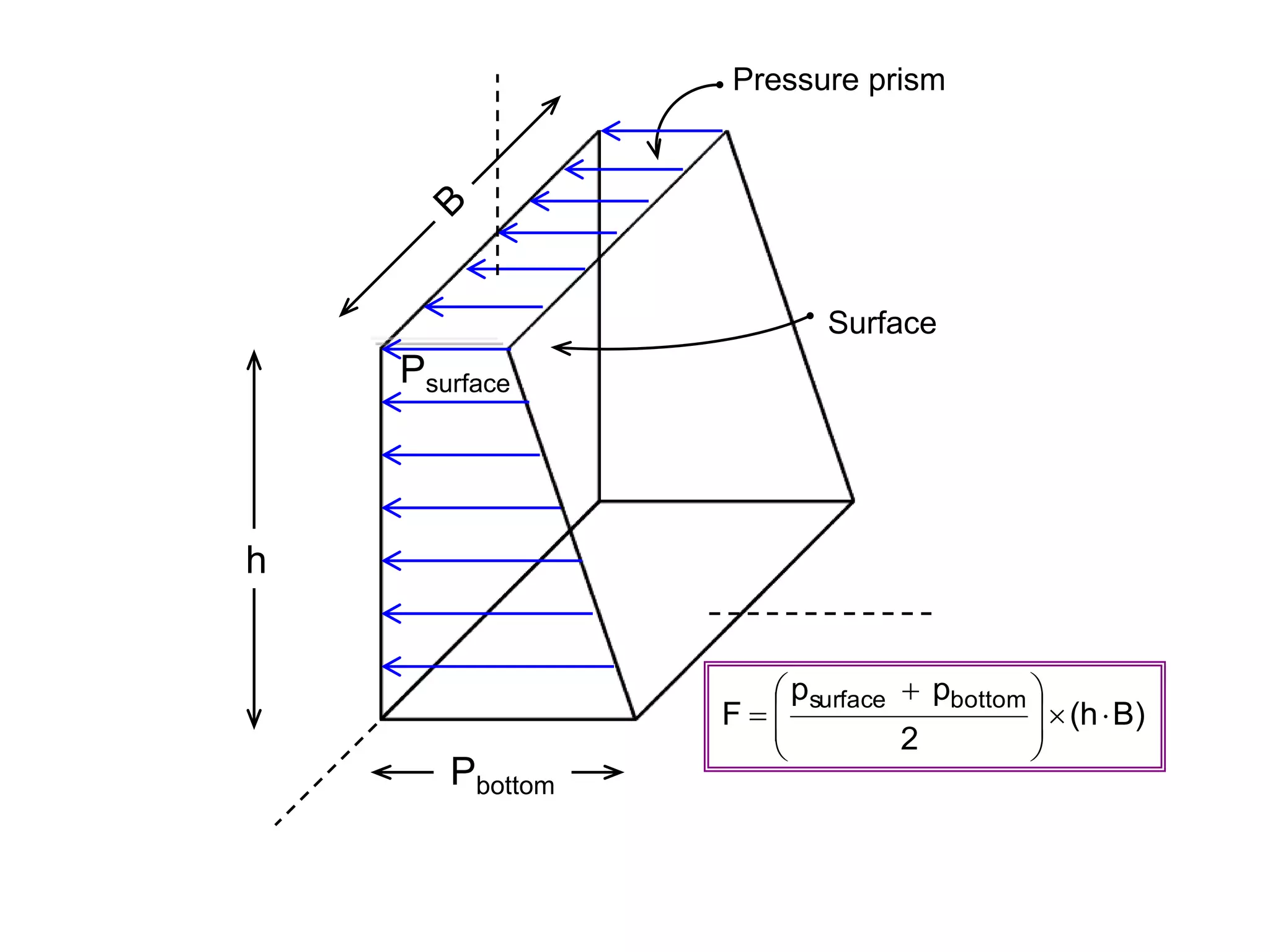

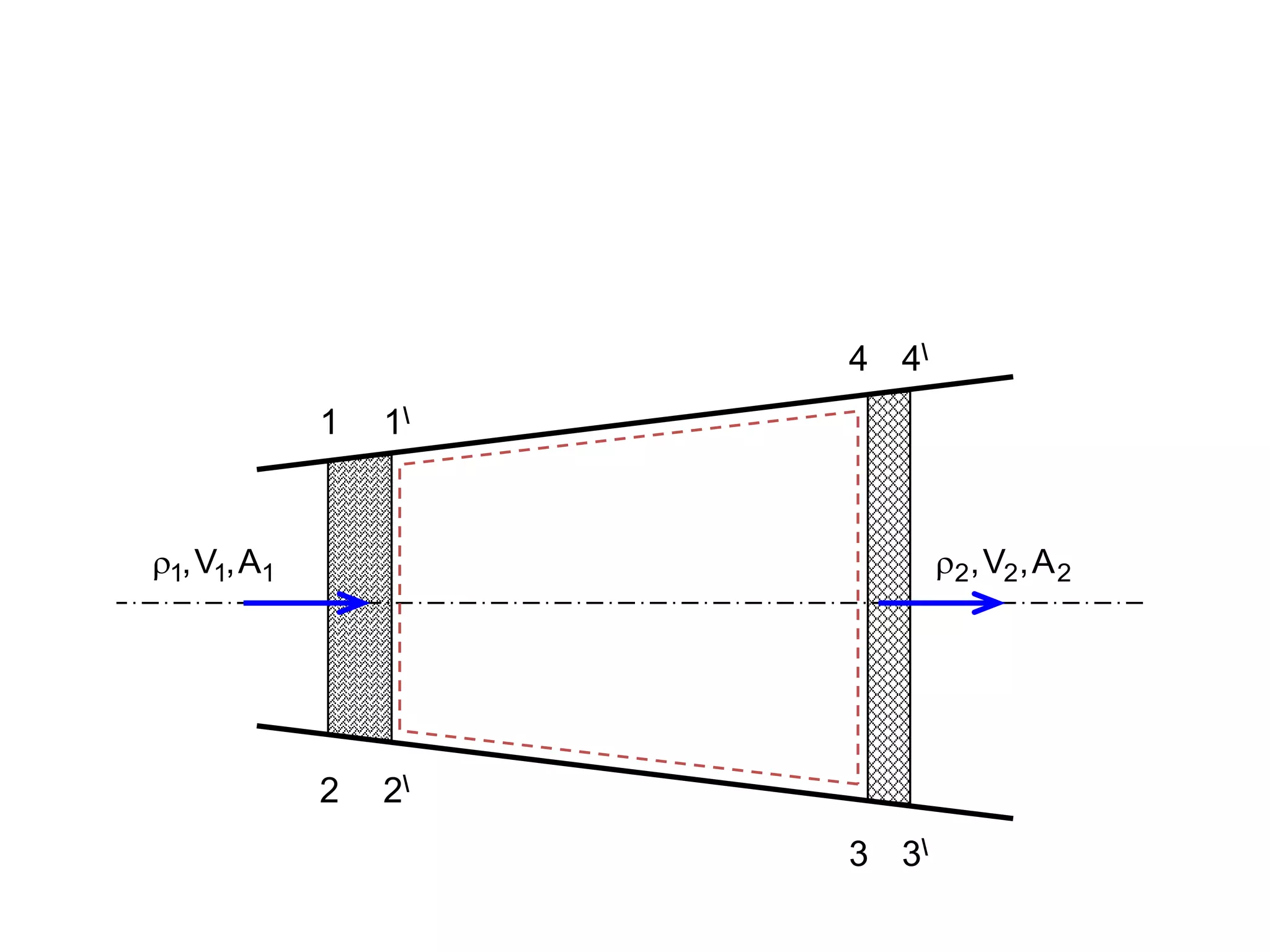

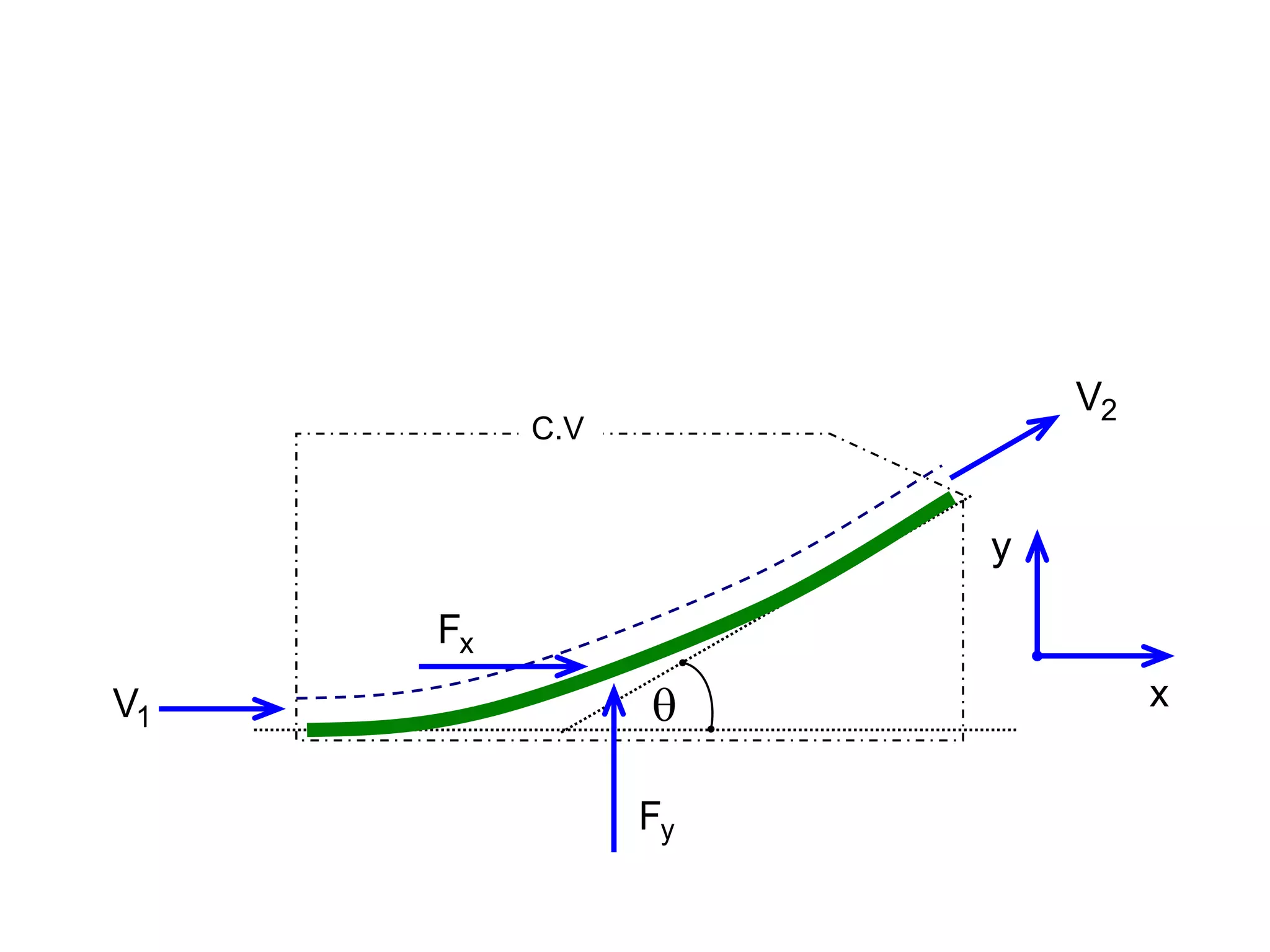

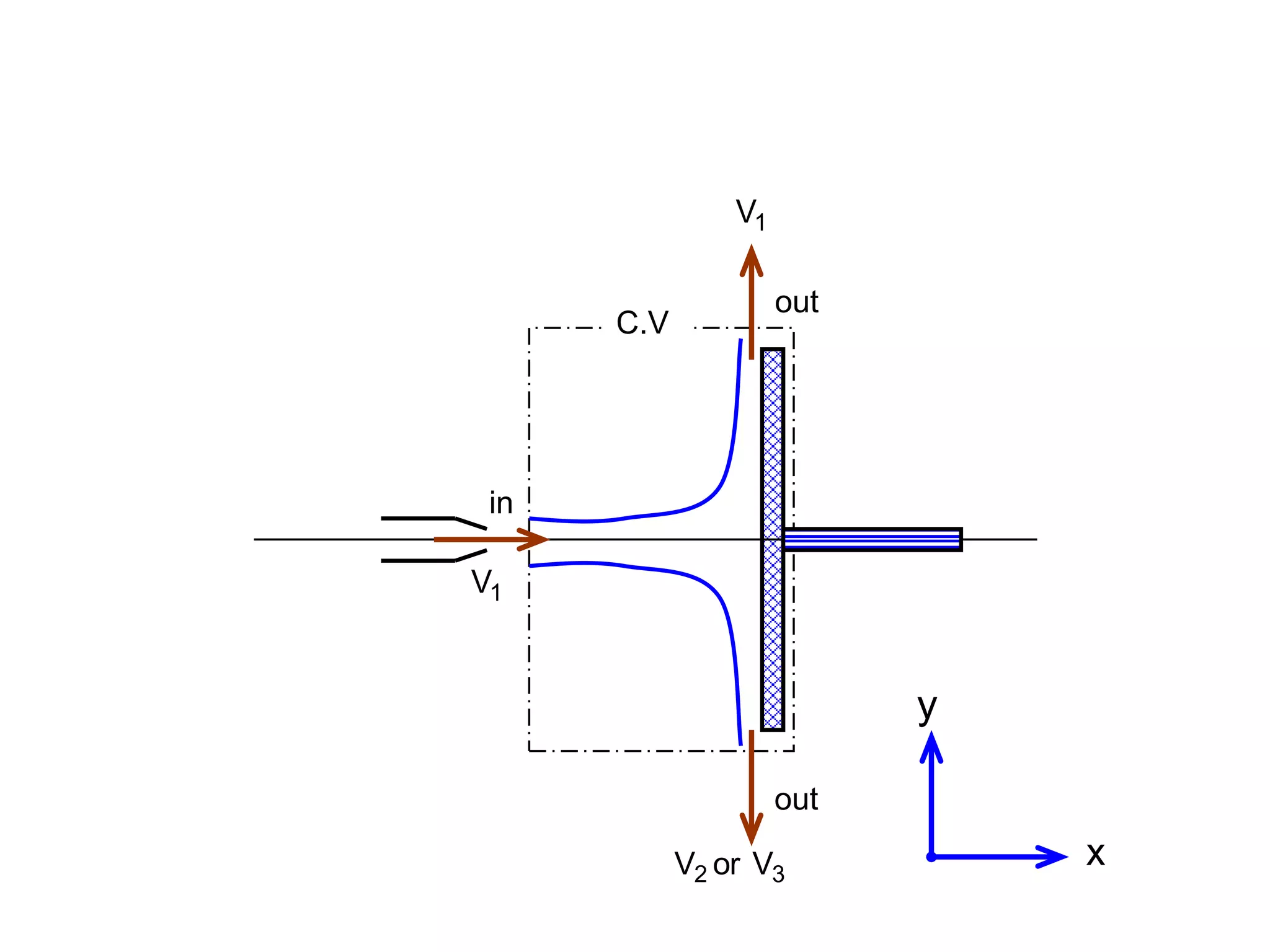

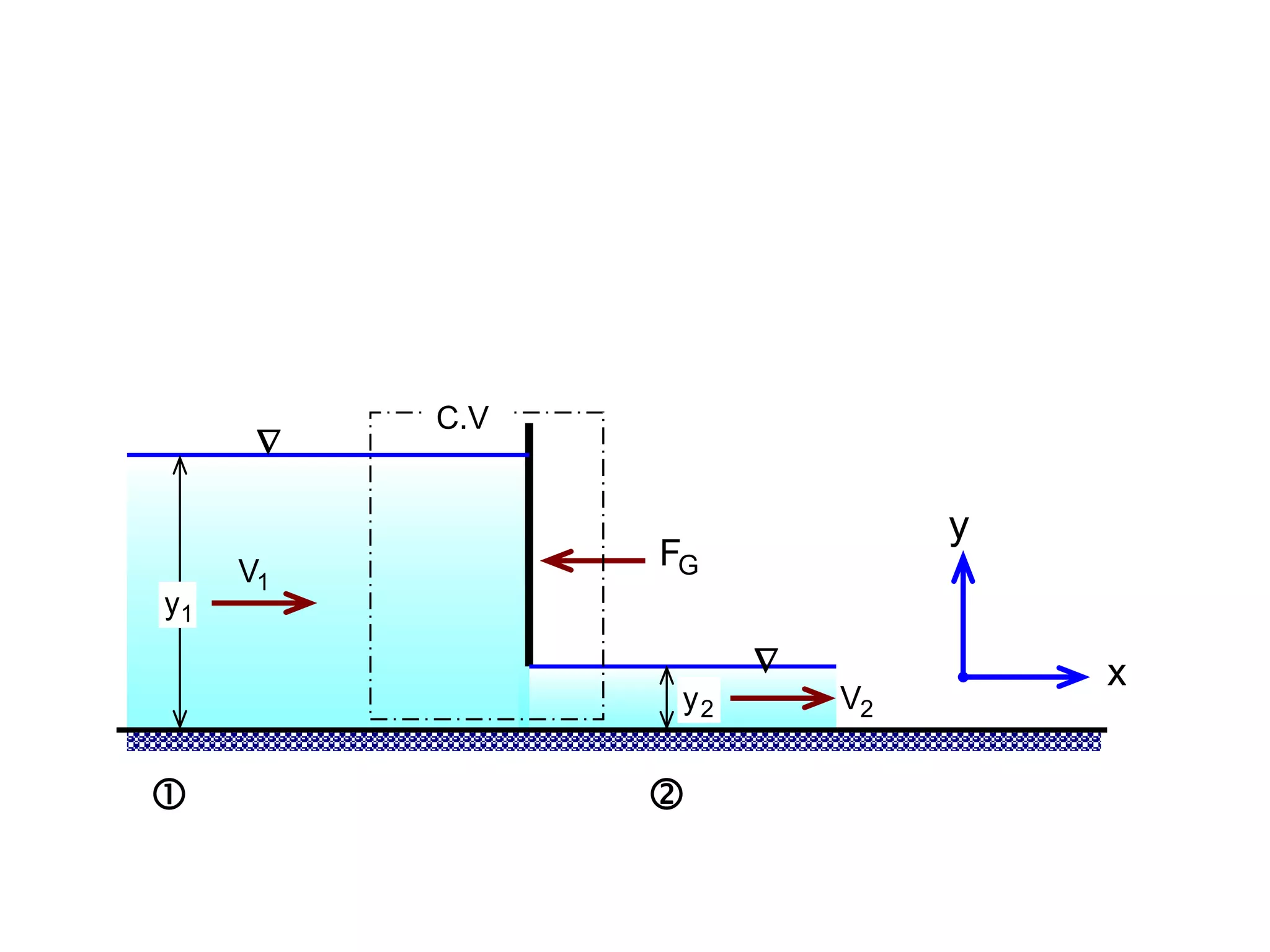

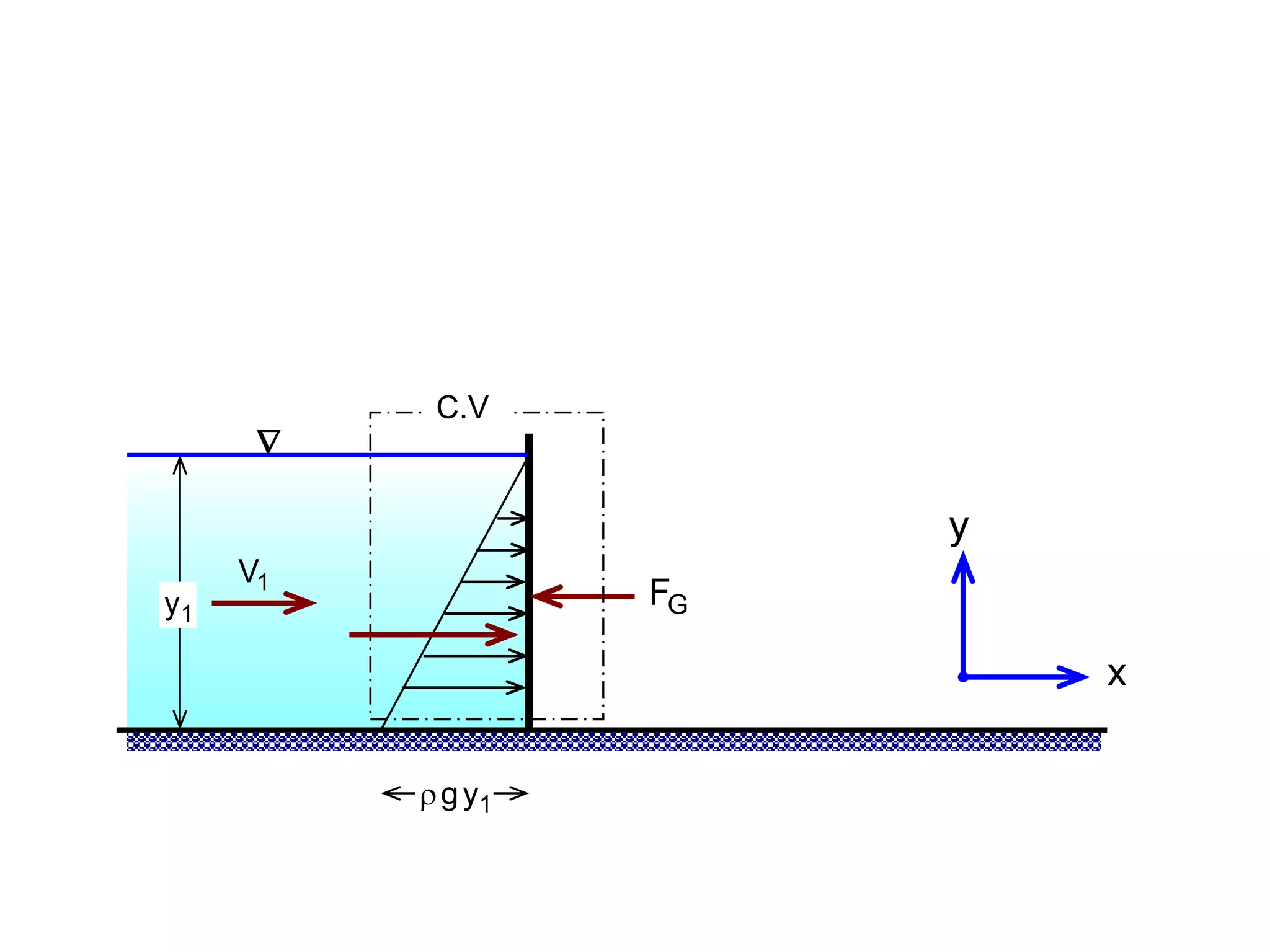

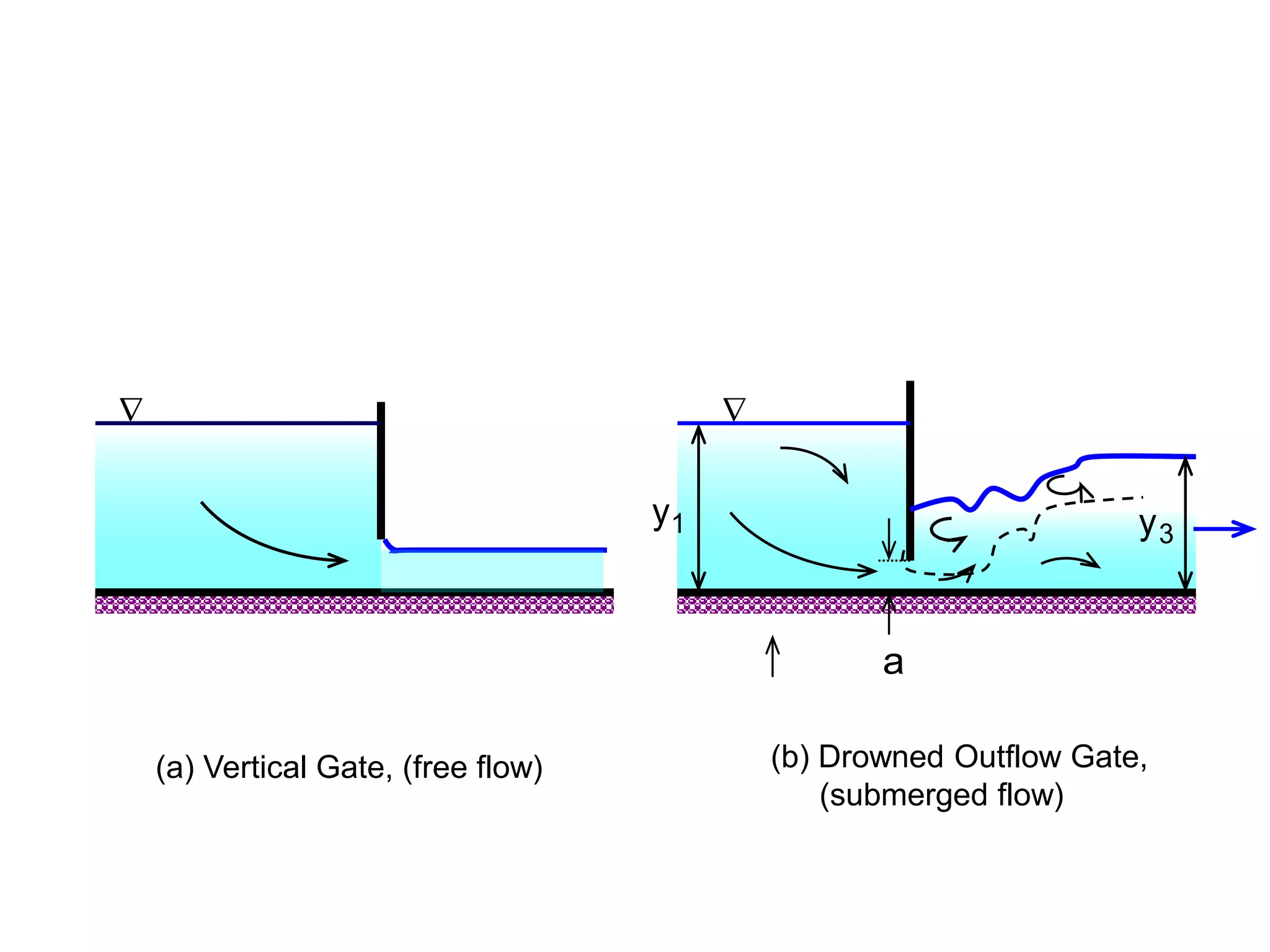

- Pressure variations in fluids undergoing acceleration or rigid body rotation

- Free surface profiles and pressure distributions in fluids in rotating or accelerated containers

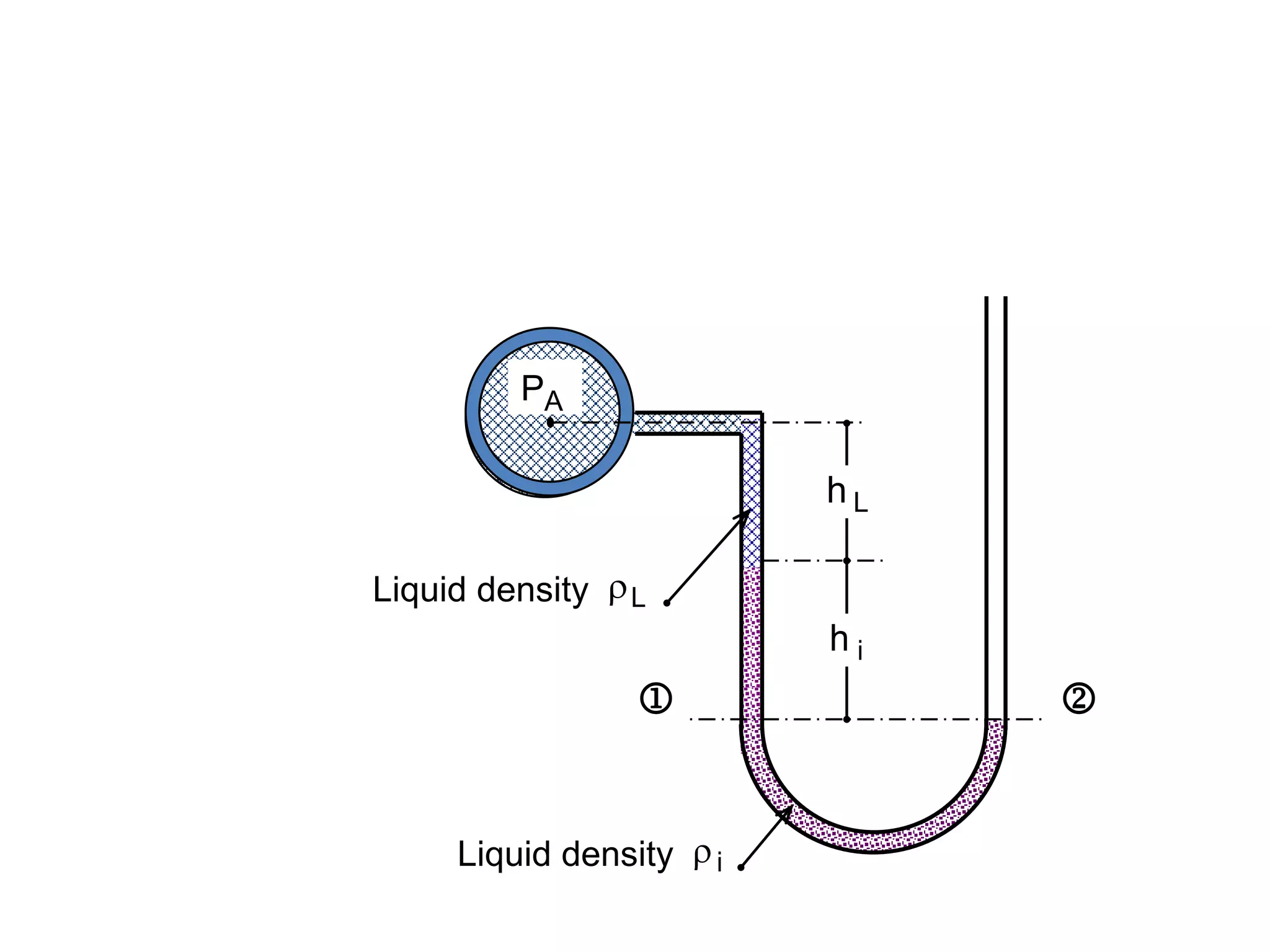

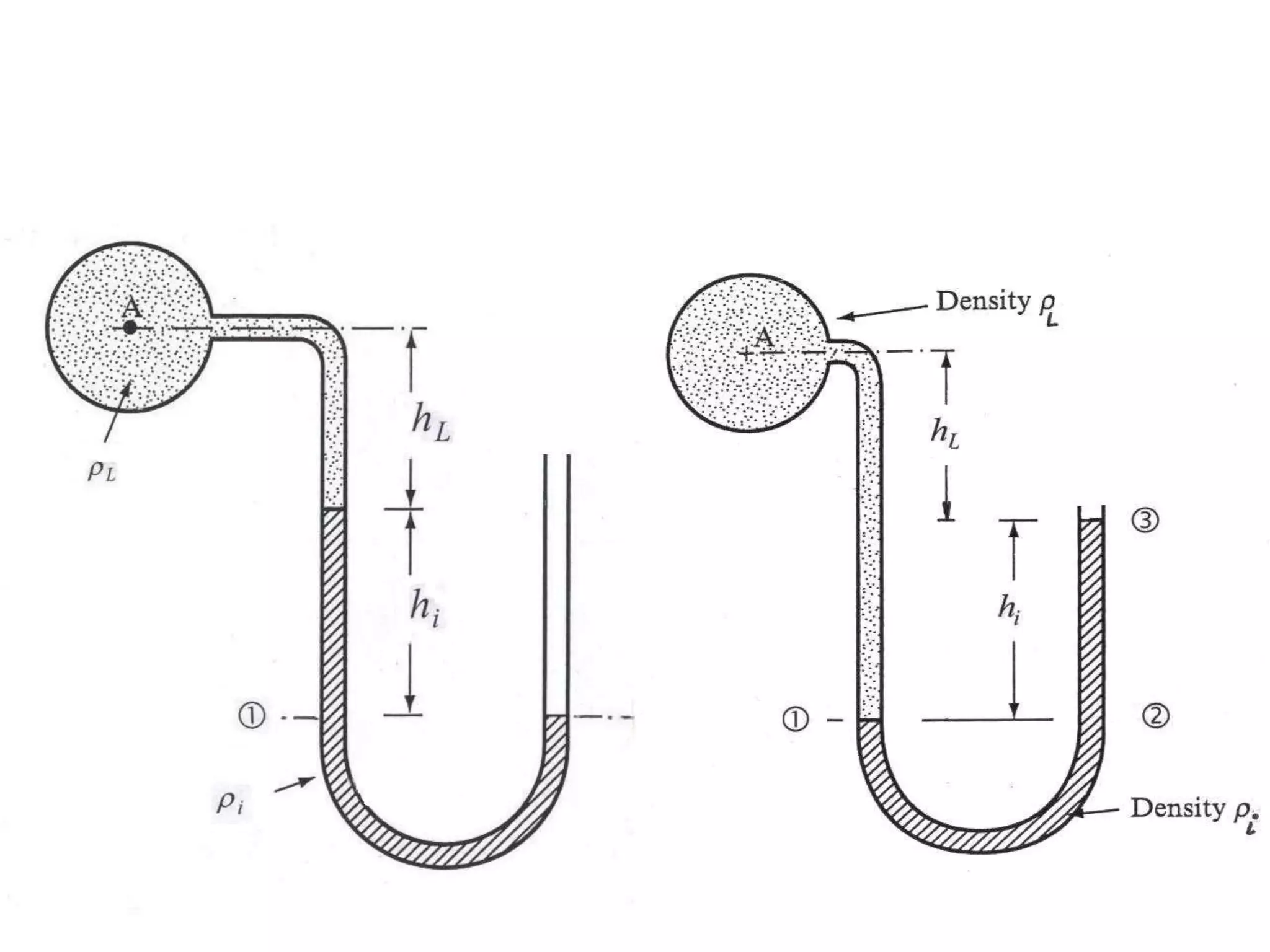

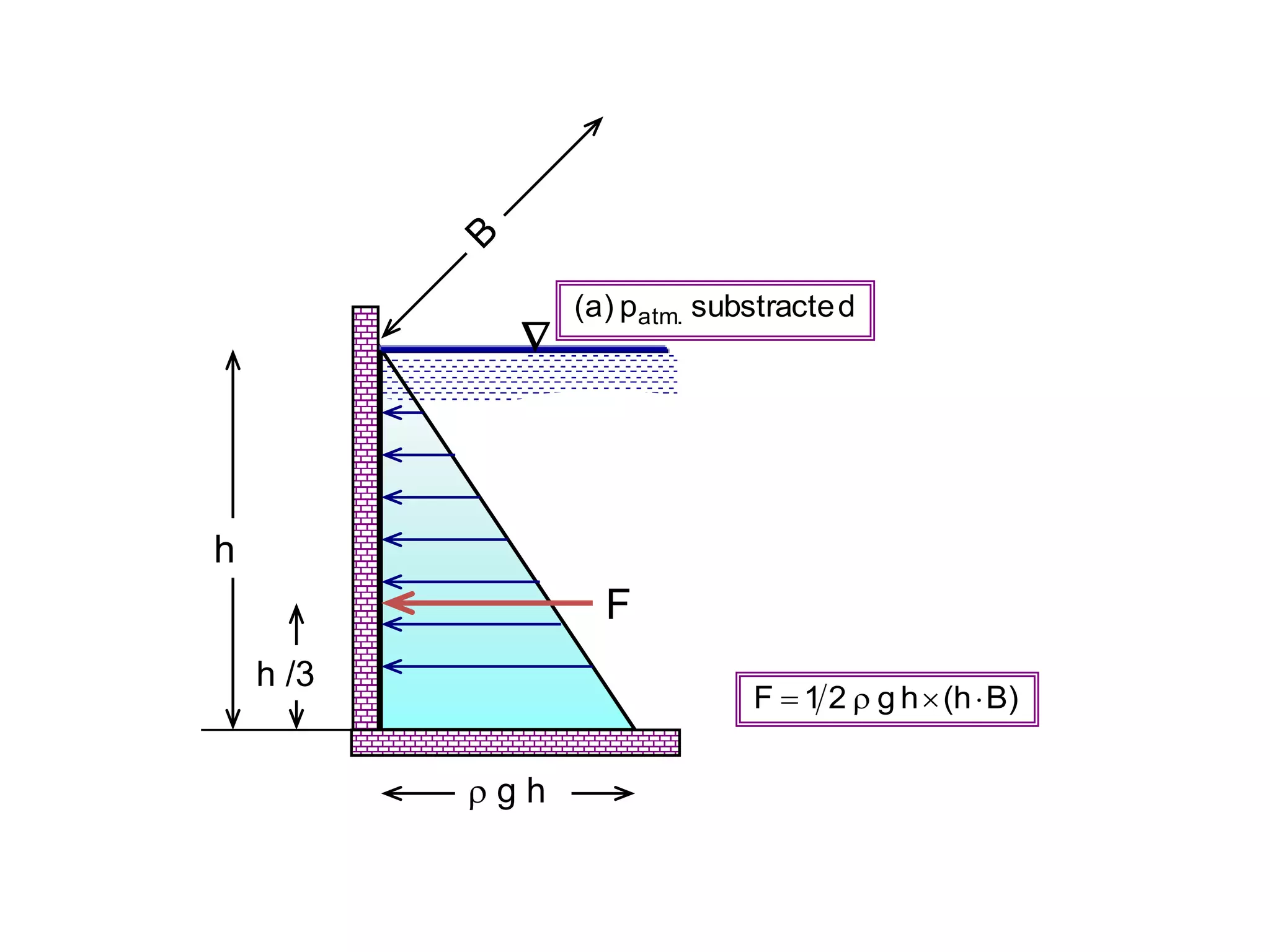

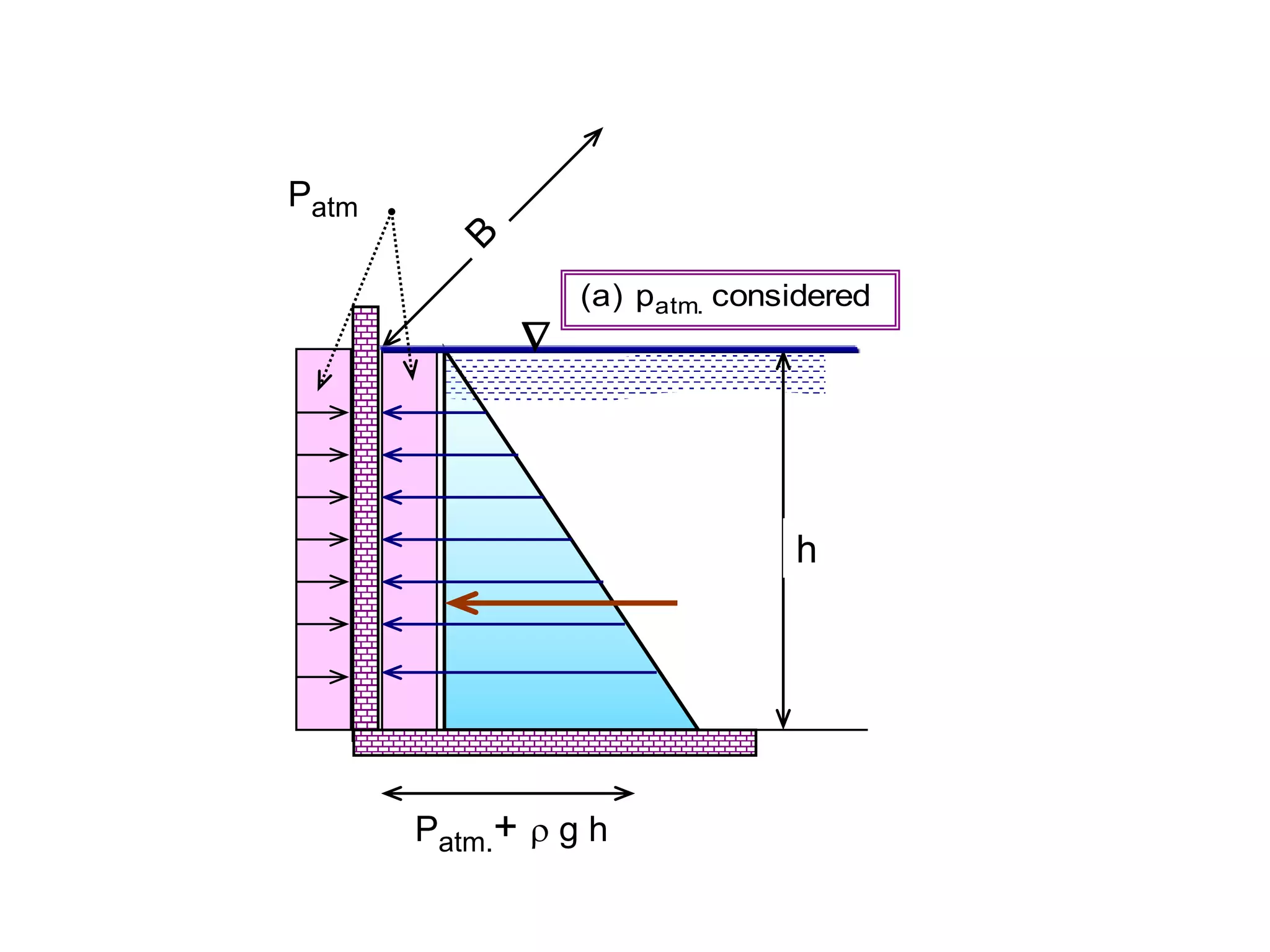

- Equations relating pressure, depth, acceleration/rotation, and density for both static and dynamic fluid situations