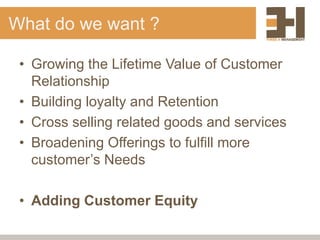

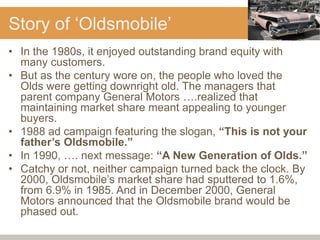

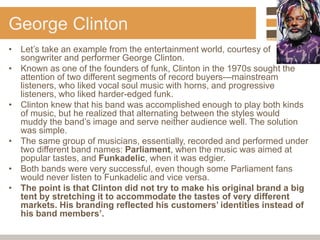

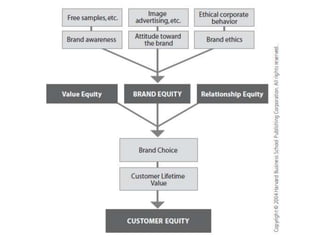

The document discusses the importance of customer-centric approaches in brand management, emphasizing that brands should serve customers rather than the other way around. It highlights case studies, such as General Motors' struggles with the Oldsmobile brand, to illustrate the need for marketers to focus on customer relationships and equity over brand loyalty. By understanding consumer behavior and preferences, companies can better adapt their branding strategies to meet the true desires of their customers.

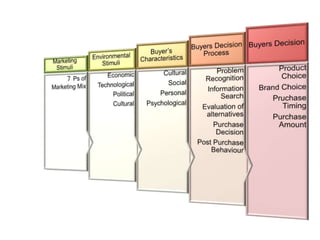

![Stages:

Post Purchase Evaluation

Satisfaction vs Dissatisfaction

Actual Purchase

Time , Access and Reference

Purchase Decision

Choosing Alternative Product Features

Evaluation of Alternatives

Criteria for Evaluation Rank Alternatives or Resume Search

Information Search

Internal Search External Search

Problem Recognition [Awareness of Need]

Desired State Actual State](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-170217084532/85/Brand-Equity-Vs-Consumer-Equity-40-320.jpg)

![What marketers need to do ?

Post Purchase Evaluation

After sales communication After sales service Customer lifetime value

Actual Purchase

Design moment of truth

Purchase Decision

Communicate Product Features Design easy process

Evaluation of Alternatives

Help consumers with information Influence by framing alternatives

Information Search

Impress consumers intensely Be present in all sources of information

Problem Recognition [Awareness of Need]

Communicate Need Sell solution](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-170217084532/85/Brand-Equity-Vs-Consumer-Equity-41-320.jpg)

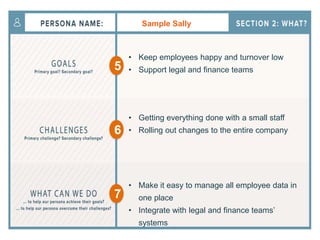

![[you type here]

• [you type here]

• [you type here]

• [you type here]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-170217084532/85/Brand-Equity-Vs-Consumer-Equity-108-320.jpg)

![[you type here]

• [you type here]

• [you type here]

• [you type here]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-170217084532/85/Brand-Equity-Vs-Consumer-Equity-109-320.jpg)

![[you type here]

• [you type here]

• [you type here]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-170217084532/85/Brand-Equity-Vs-Consumer-Equity-110-320.jpg)

![[you type here]

• [you type here]

• [you type here]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-170217084532/85/Brand-Equity-Vs-Consumer-Equity-111-320.jpg)

![[you type here]

• [you type here]

• [you type here]

• [you type here]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-170217084532/85/Brand-Equity-Vs-Consumer-Equity-112-320.jpg)

![[you type here]

• [you type here]

• [you type here]

• [you type here]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-170217084532/85/Brand-Equity-Vs-Consumer-Equity-113-320.jpg)

![[you type here]

• [you type here]

• [you type here]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-170217084532/85/Brand-Equity-Vs-Consumer-Equity-114-320.jpg)

![[you type here]

• [you type here]

• [you type here]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-170217084532/85/Brand-Equity-Vs-Consumer-Equity-115-320.jpg)

![[you type here]

• [you type here]

• [you type here]

• [you type here]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-170217084532/85/Brand-Equity-Vs-Consumer-Equity-116-320.jpg)

![[you type here]

• [you type here]

• [you type here]

• [you type here]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-170217084532/85/Brand-Equity-Vs-Consumer-Equity-117-320.jpg)

![[you type here]

• [you type here]

• [you type here]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-170217084532/85/Brand-Equity-Vs-Consumer-Equity-118-320.jpg)

![[you type here]

• [you type here]

• [you type here]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-170217084532/85/Brand-Equity-Vs-Consumer-Equity-119-320.jpg)