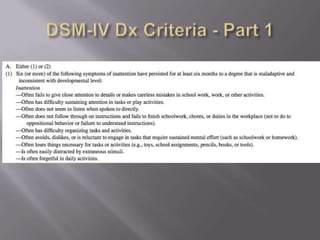

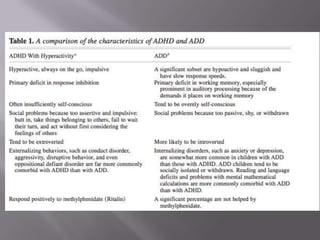

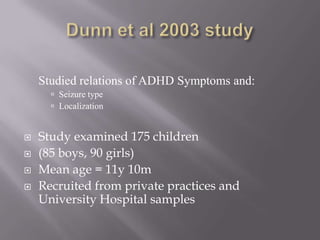

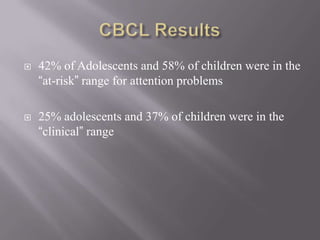

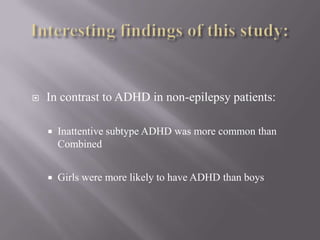

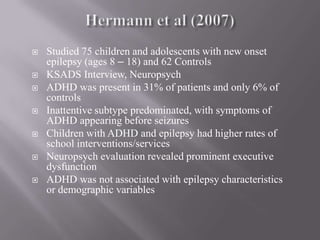

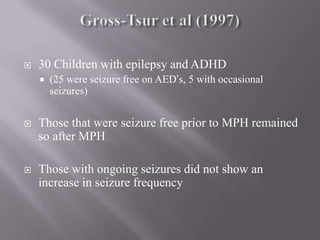

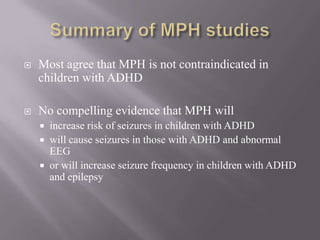

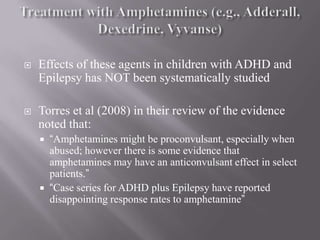

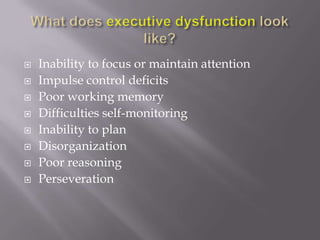

This document discusses attention and working memory in pediatric epilepsy. It provides a brief history of ADHD and reviews the diagnostic criteria. Attention problems are common in epilepsy and may account for academic underachievement. While rates of ADHD in epilepsy vary, studies find prevalence is higher than the general population. Methylphenidate may be safely used to treat comorbid ADHD and epilepsy. Executive dysfunction, including problems with working memory, are seen in many children with epilepsy and can impact academic performance.