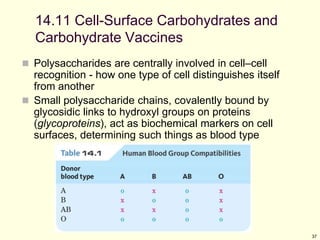

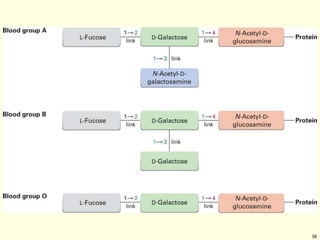

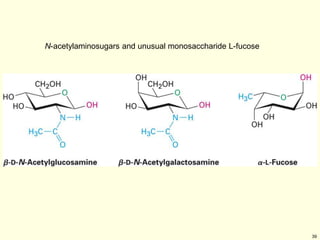

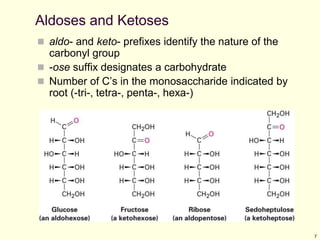

This chapter discusses carbohydrates, which are distributed widely in nature and serve important structural and metabolic functions. Carbohydrates can be classified as monosaccharides, disaccharides, or polysaccharides depending on the number of sugar monomers present. Monosaccharides like glucose are the basic building blocks and exist in both open-chain and cyclic forms. Disaccharides join two monosaccharides, while polysaccharides contain long chains of monosaccharides like cellulose and starch. Carbohydrates play key roles in energy storage, structure of plants and organisms, and cell recognition through glycoproteins on cell surfaces.

![18

Mutarotation

The two anomers of D-glucopyranose can be

crystallized and purified

a-D-glucopyranose melts at 146° and its specific

rotation, [a]D = 112.2°;

b-D-glucopyranose melts at 148–155°C with a

specific rotation of [a]D = 18.7°

Rotation of solutions of either pure anomer slowly

changes due to slow conversion of the pure anomers

into a 37:63 equilibrium mixture of a:b called

mutarotation](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter14-211208064925/85/biomolecules-carbohydrates-18-320.jpg)