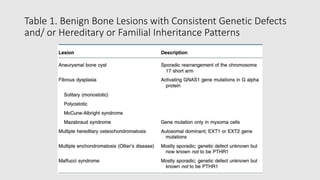

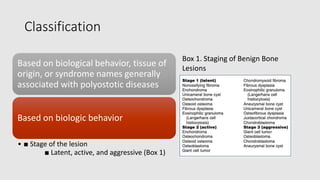

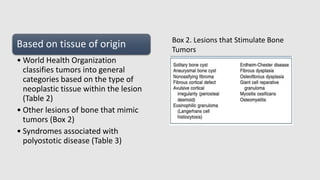

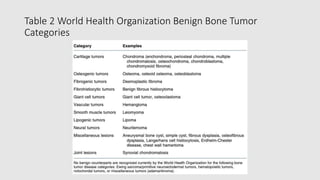

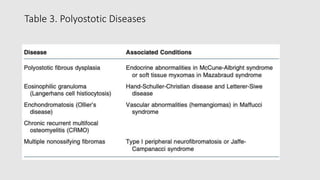

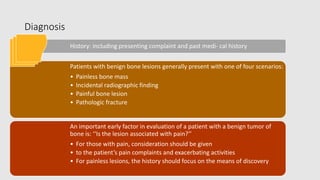

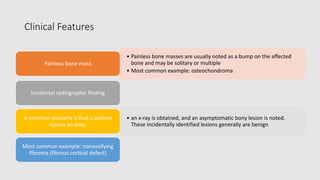

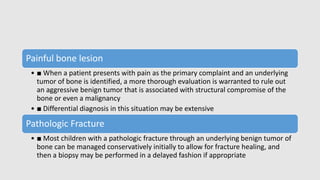

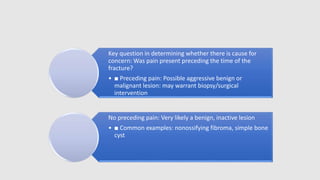

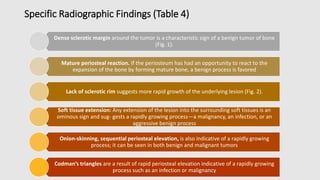

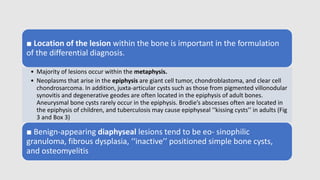

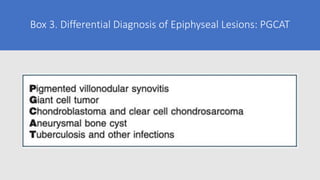

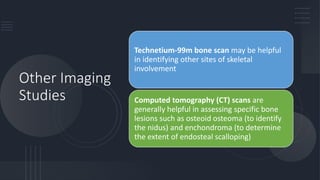

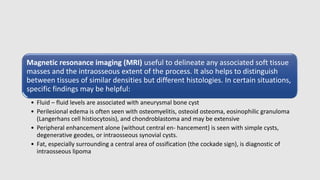

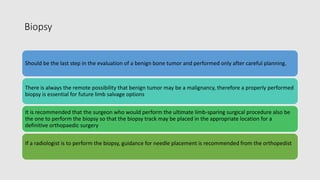

Benign tumors of bone can exhibit a variety of behaviors requiring different treatment options. While most have no known cause, a few are associated with genetic syndromes or conditions. They are classified based on characteristics like behavior, tissue type, and whether they affect one or multiple bones. Diagnosis involves history, exam, imaging like x-rays and MRI to identify location and features. If still uncertain, biopsy may be needed to confirm but should be done carefully after other evaluation to avoid problems for future treatment if needed.