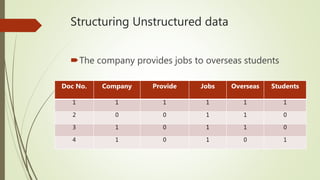

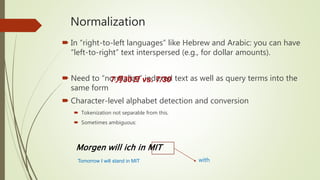

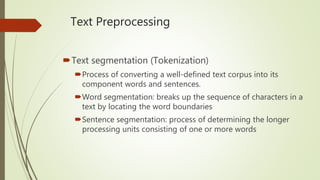

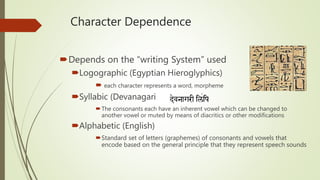

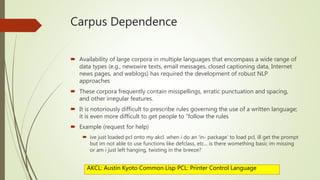

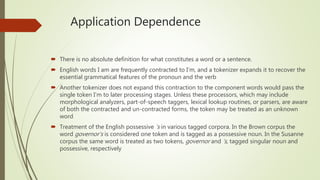

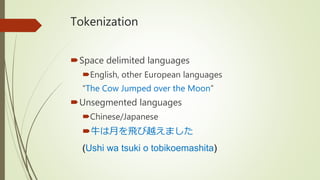

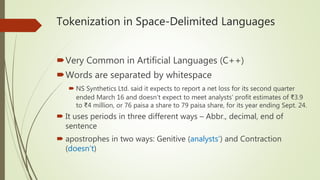

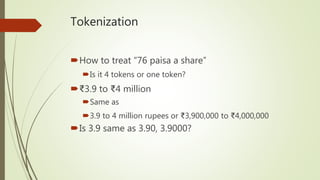

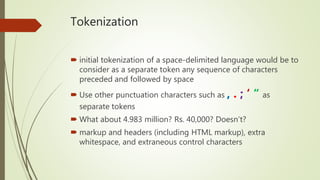

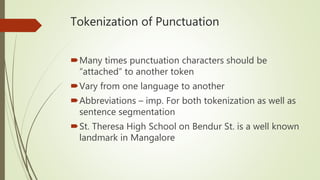

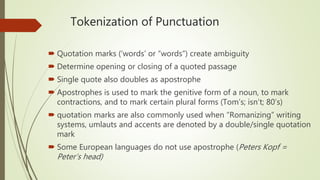

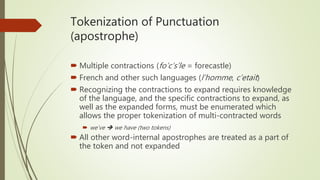

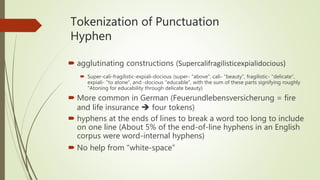

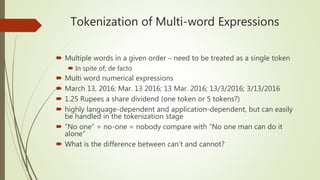

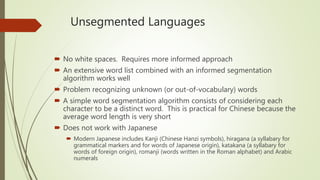

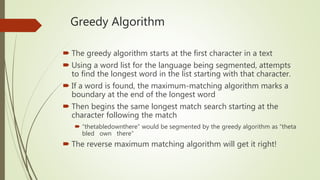

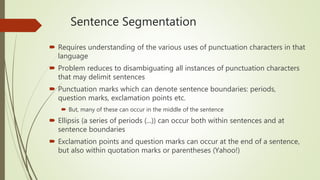

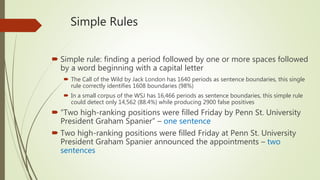

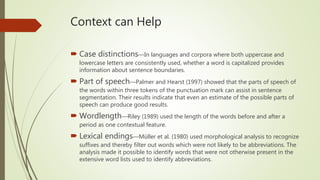

This document discusses basic techniques in natural language processing (NLP) including structuring unstructured text, text preprocessing, and tokenization. It explains how to structure unstructured text into a tabular format for analysis. It then covers various text preprocessing techniques like character encoding identification, language identification, and normalization. Finally, it describes different approaches to tokenization for space-delimited and unsegmented languages, including handling punctuation, multi-word expressions, and sentence segmentation.