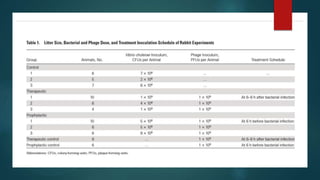

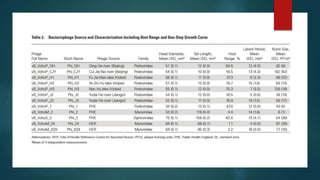

This study investigated using bacteriophage therapy to treat cholera. A single bacteriophage, Phi_1, was found to effectively control cholera in an infant rabbit model when given prophylactically or therapeutically, with phage-treated animals showing no clinical signs of disease. No phage-resistant bacterial mutants were found in the animals despite extensive searching. This provides the first evidence that a single phage could treat cholera without detectable resistance and suggests clinical trials in humans should be considered.