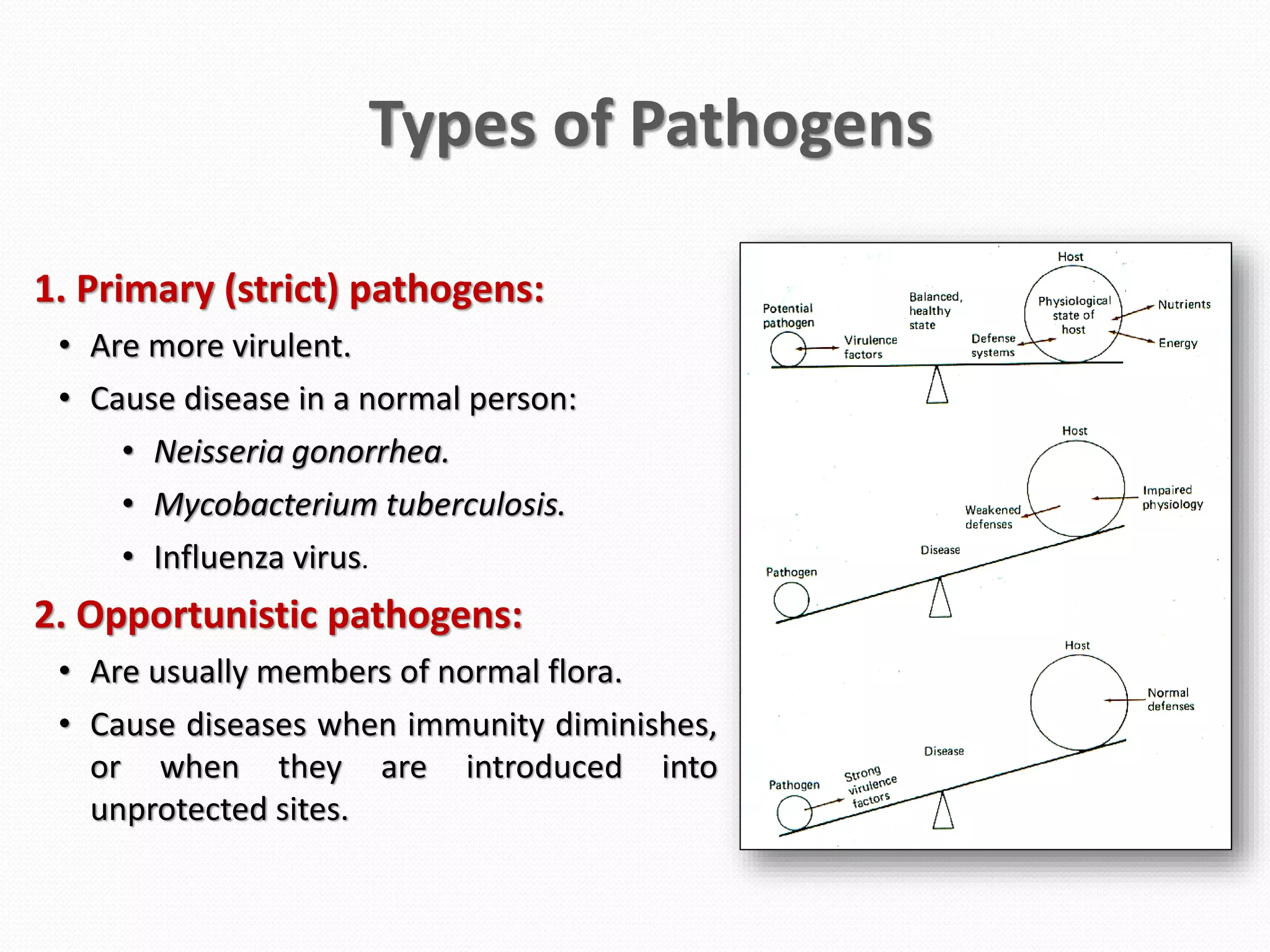

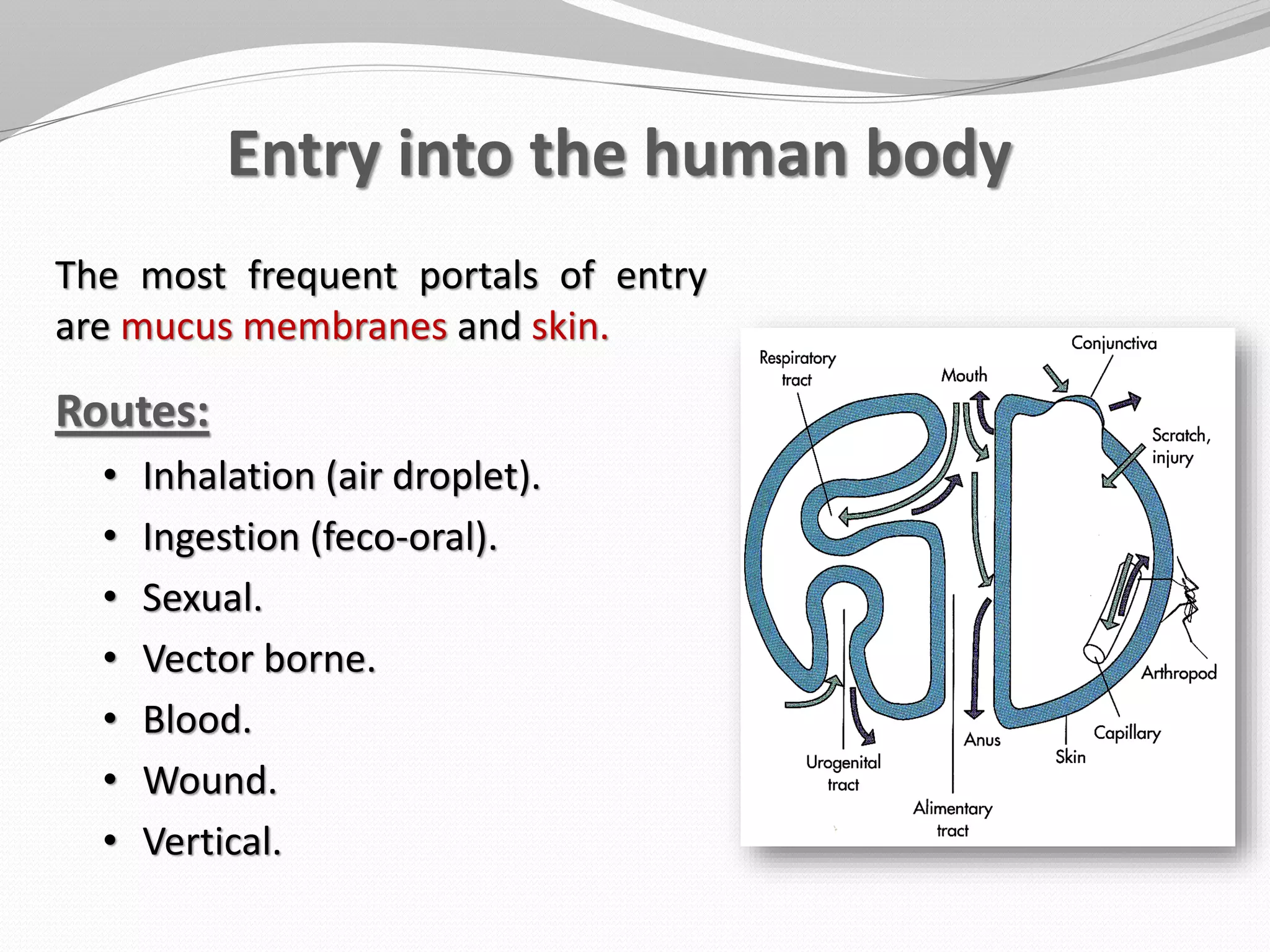

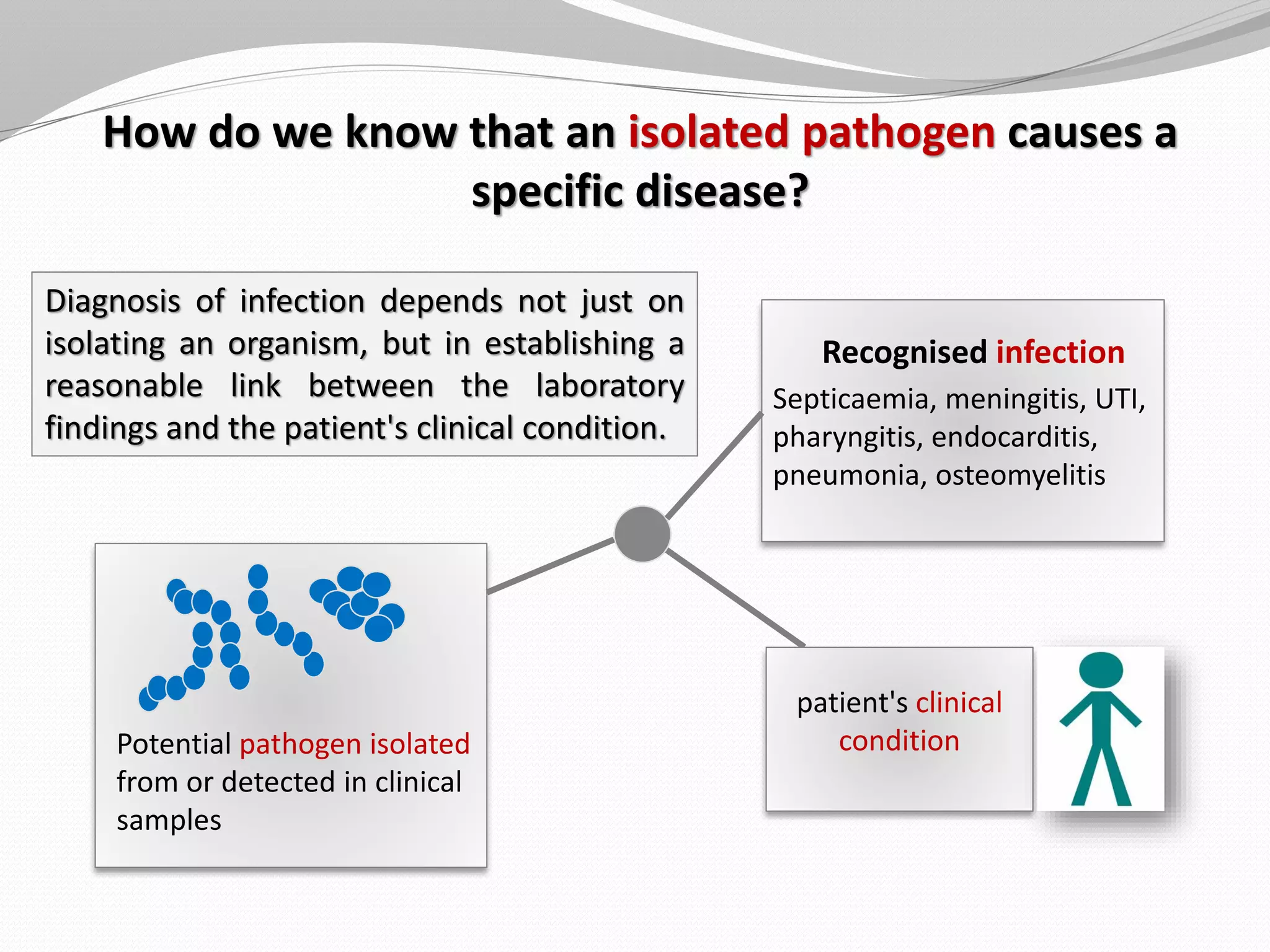

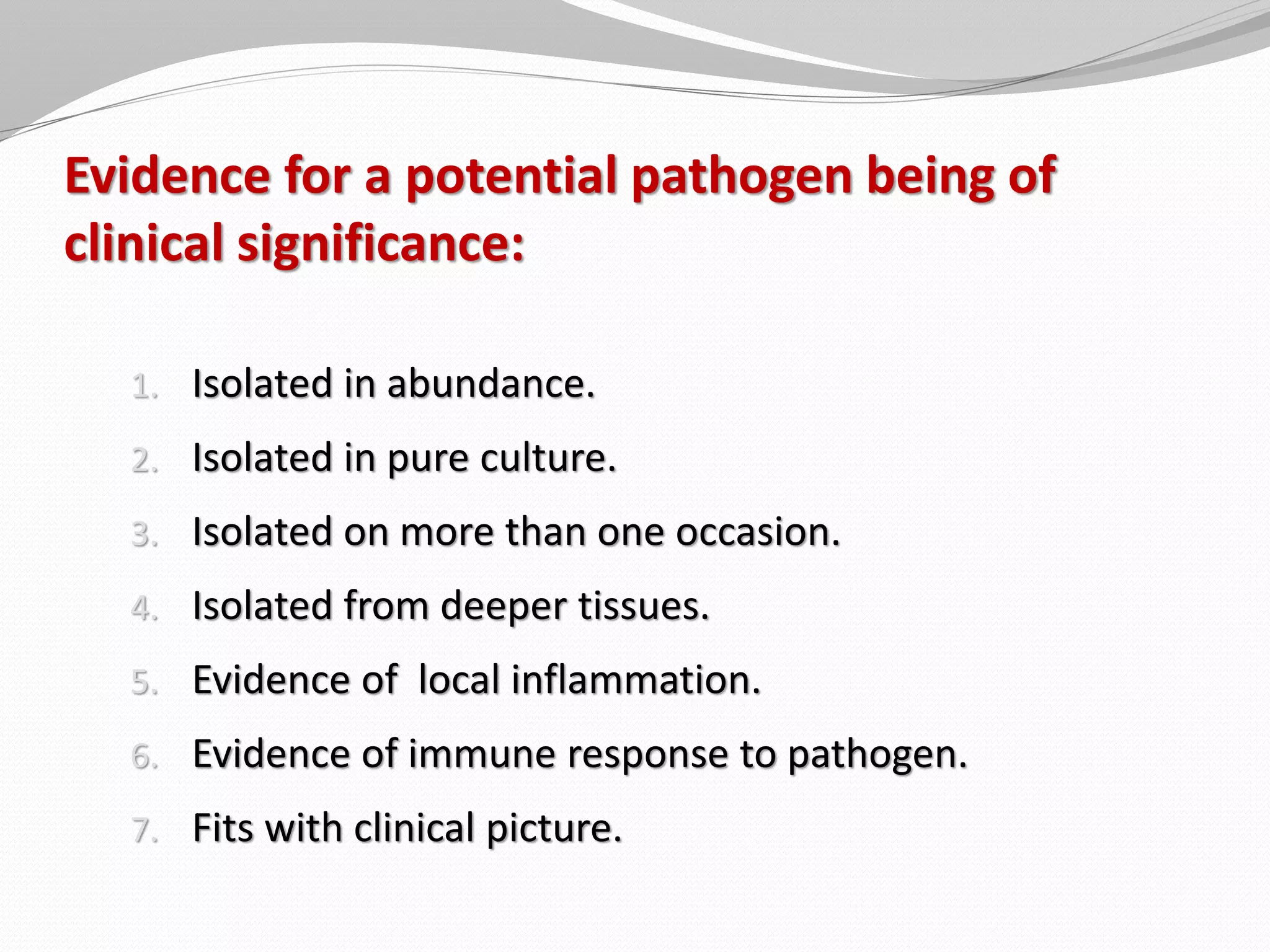

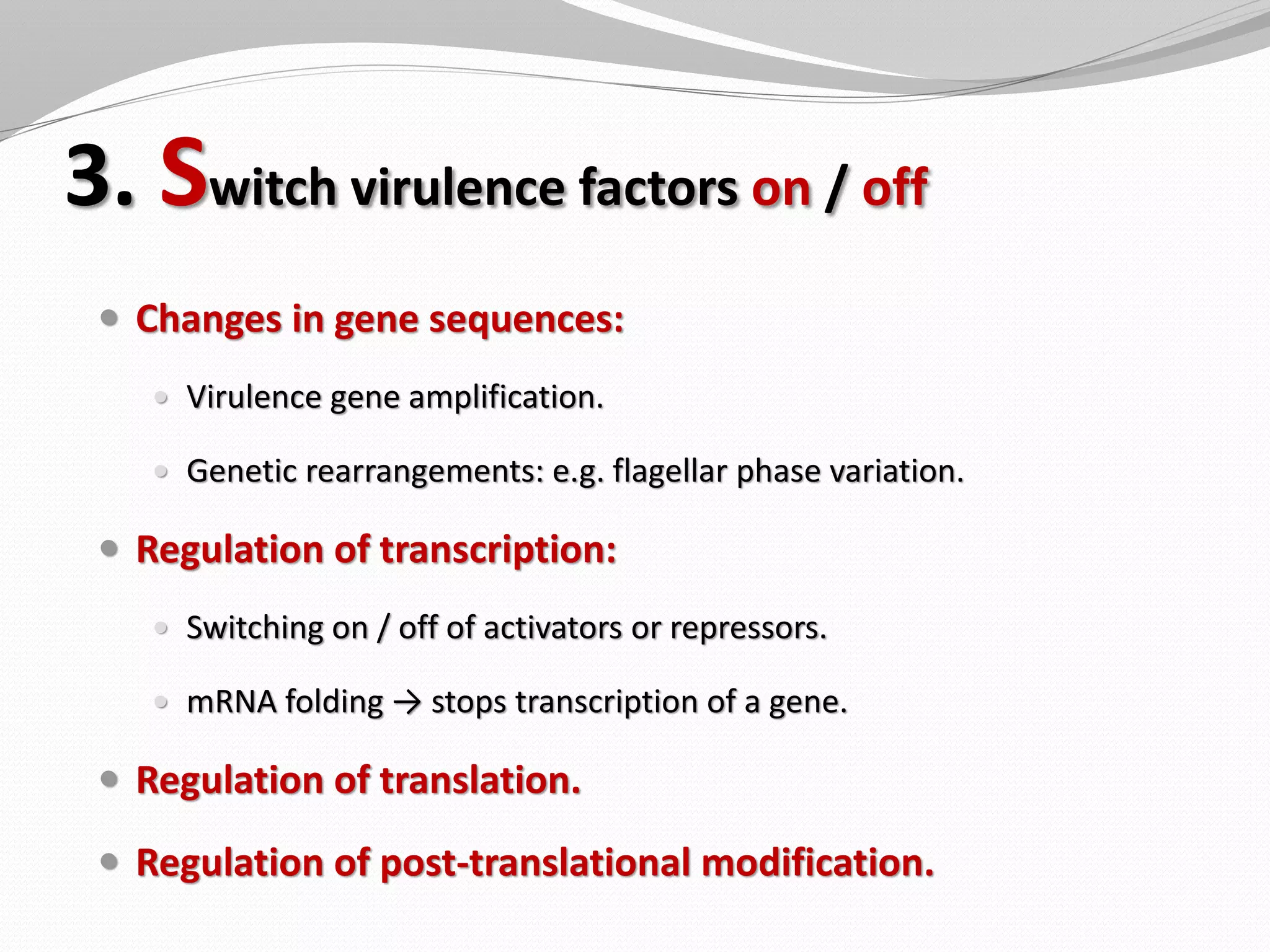

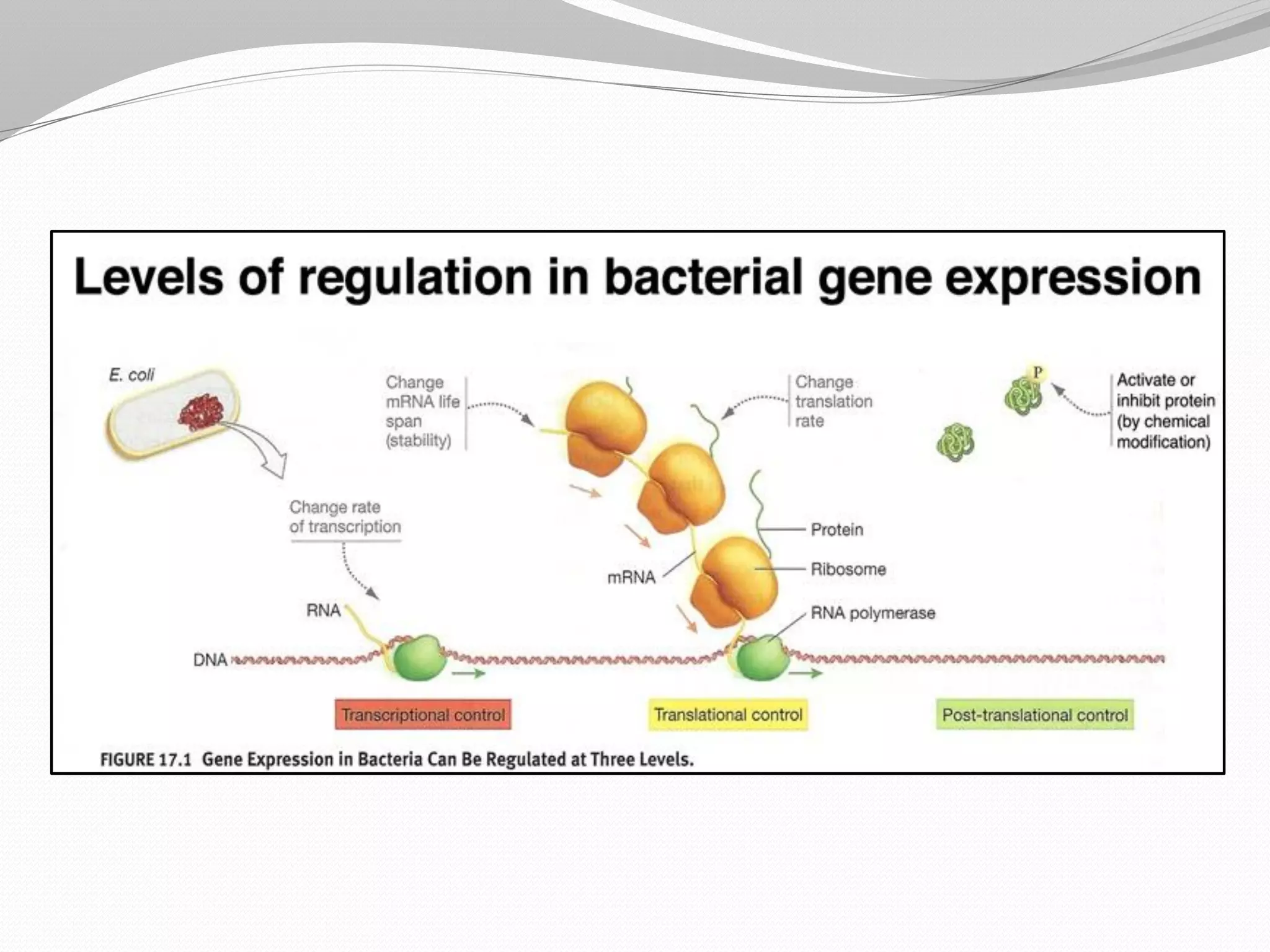

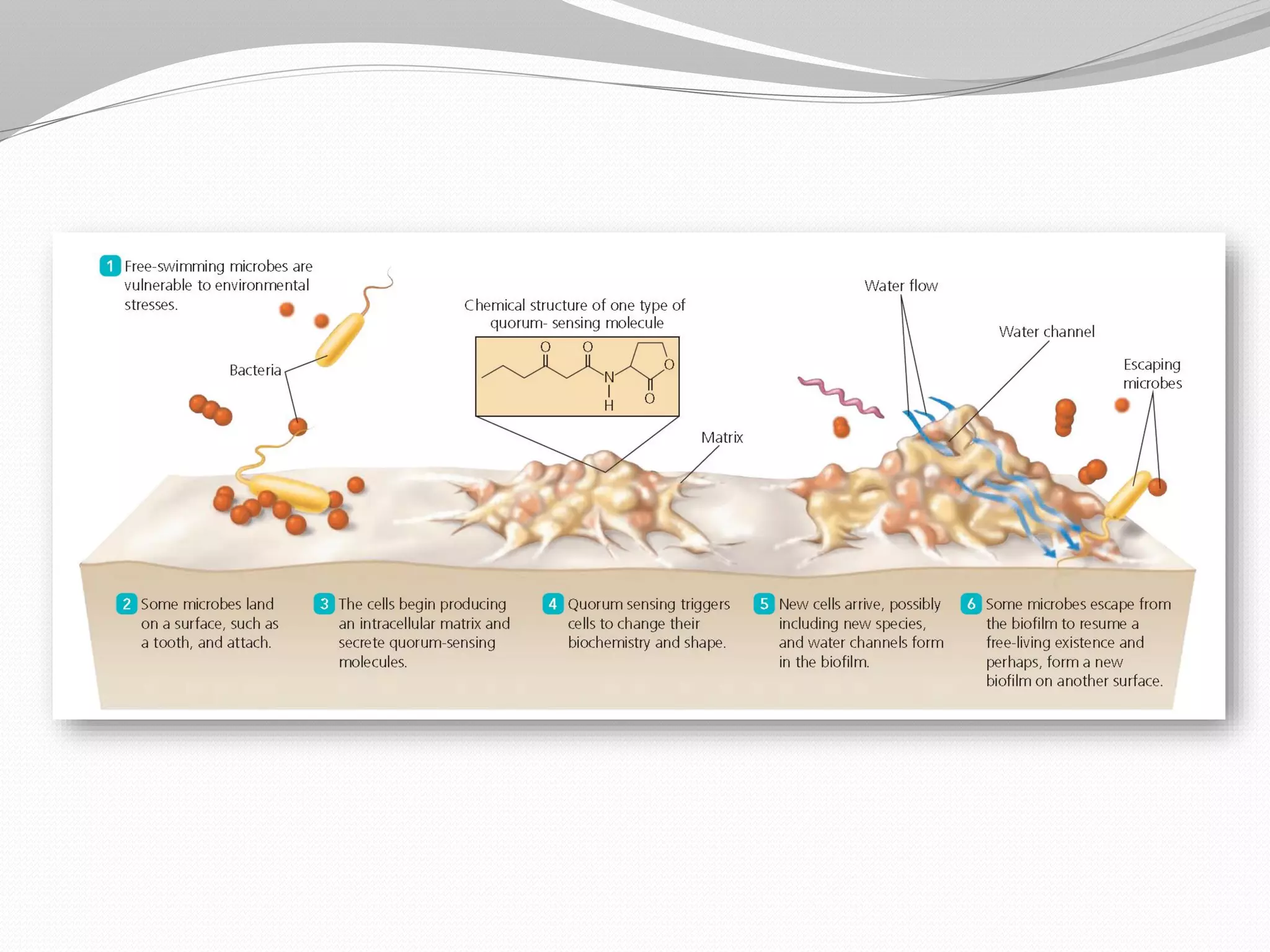

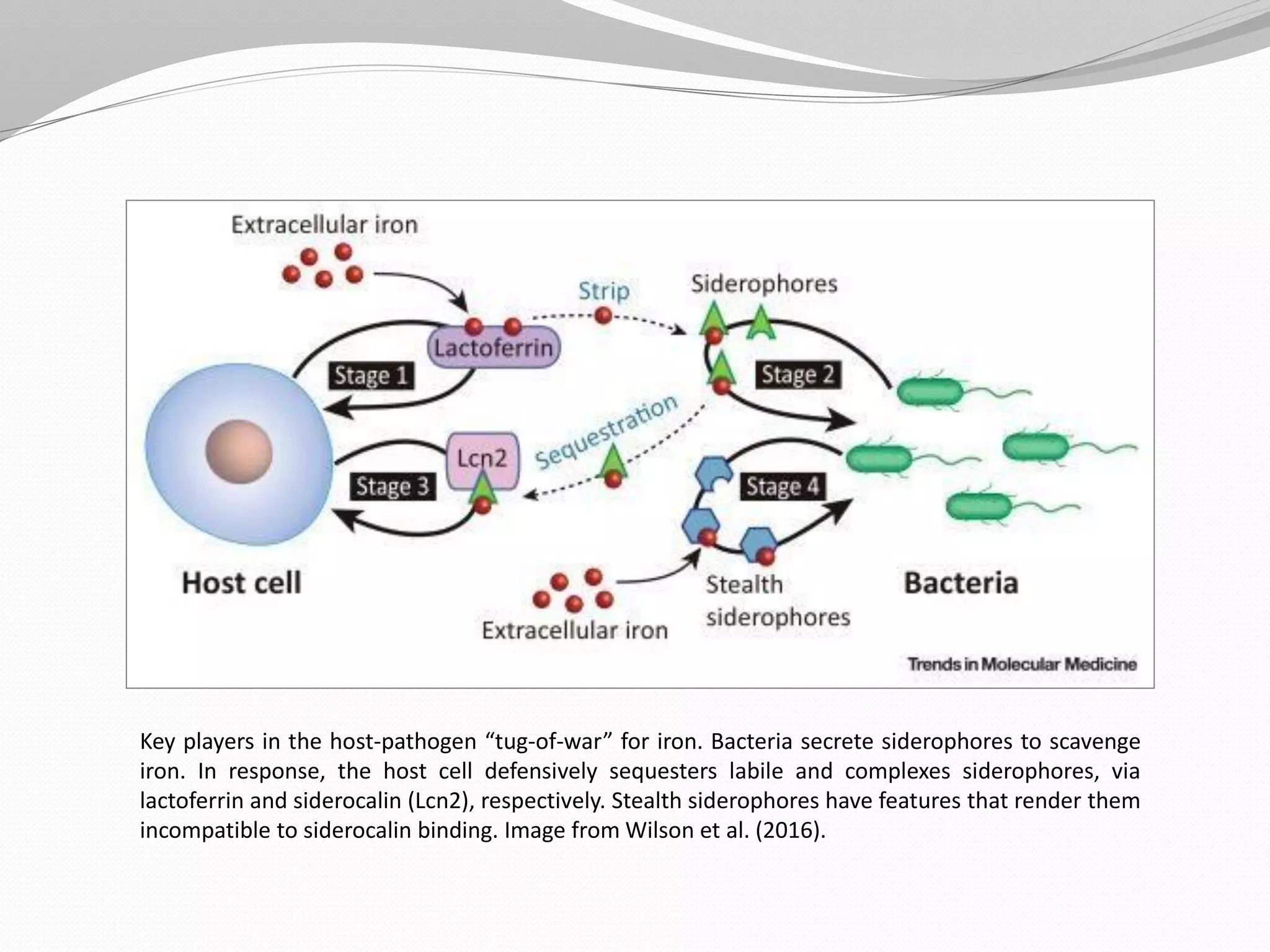

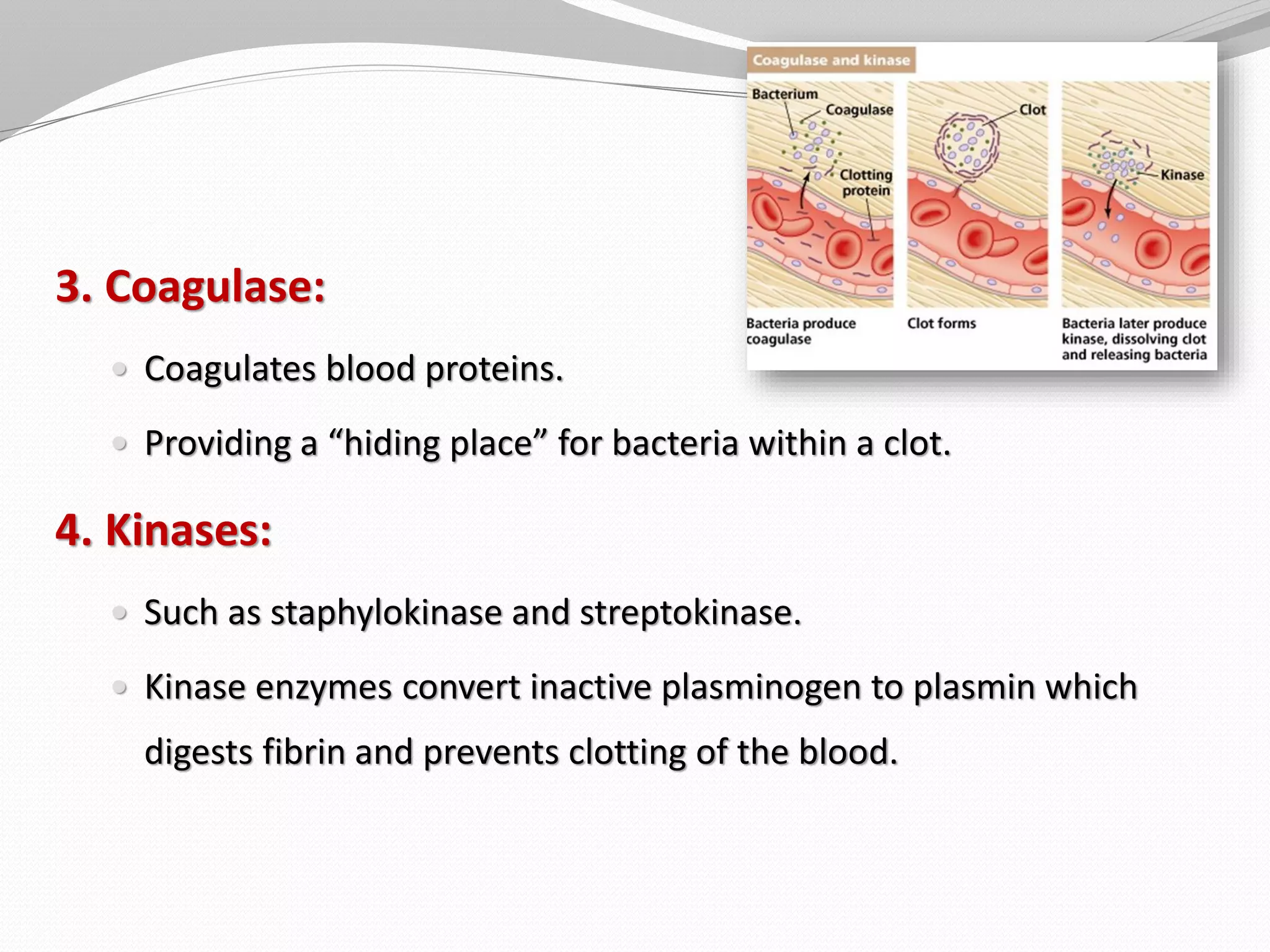

The document discusses various aspects of bacterial pathogenesis and infection. It defines key terms like infection, pathogenicity, and virulence. It describes the host susceptibility factors and different types of pathogens. It explains the various routes of bacterial entry into the human body and the patterns of infections. It discusses Koch's postulates and how pathogens are linked to specific diseases. It also summarizes the multistep process bacteria use to cause infection, including acquiring virulence genes, sensing the environment, expressing virulence factors, adhering to and invading tissues, acquiring nutrients, surviving host defenses, and evading the immune system.