This thesis proposes and evaluates a compressive sensing (CS)-based indoor positioning and tracking system using received signal strength (RSS) from wireless local area network access points. The system is designed and implemented on mobile devices with limited resources.

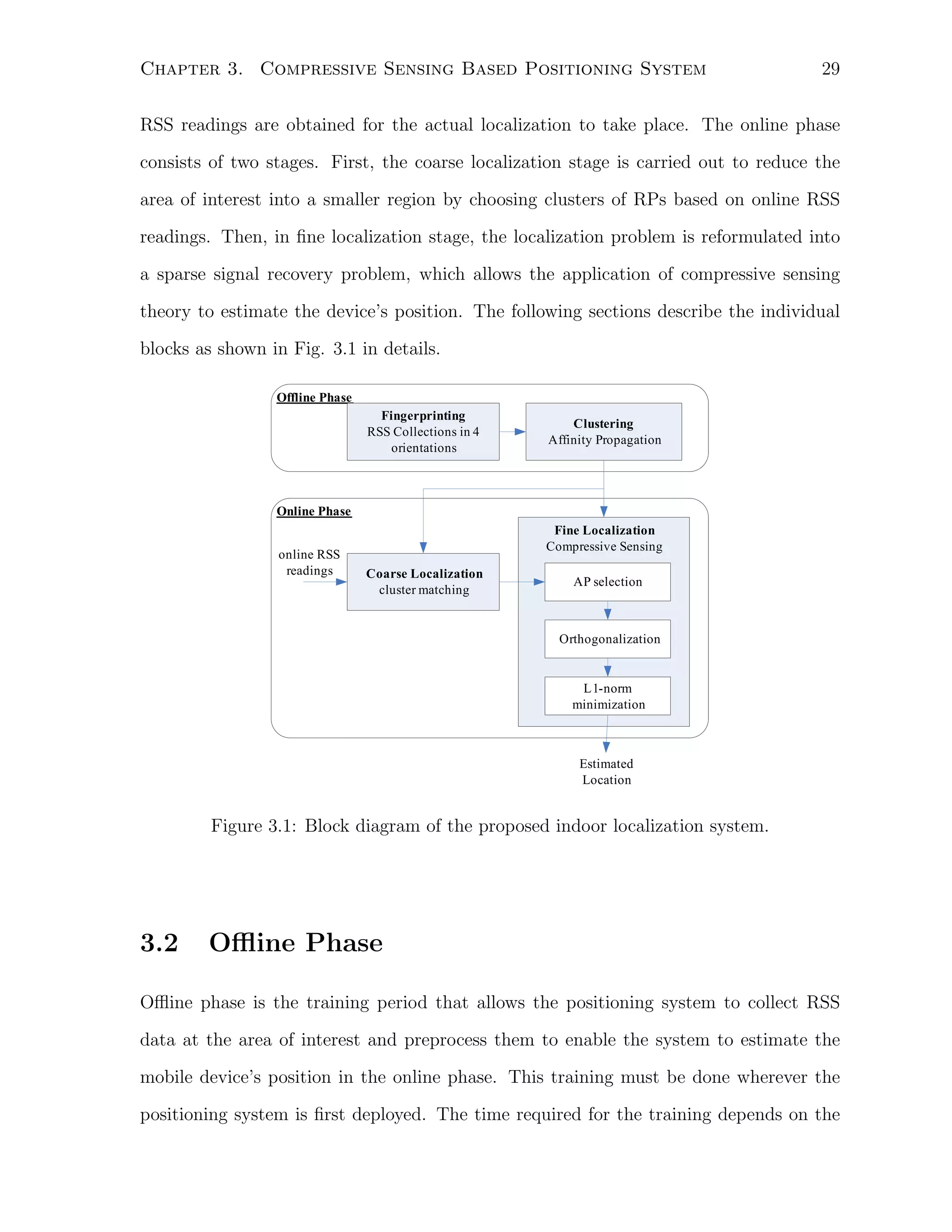

In the offline phase, RSS fingerprints are collected and clustered using affinity propagation. In the online phase, coarse localization is done by matching RSS measurements to precomputed clusters, and fine localization refines the position using CS recovery on the sparse location signal.

An indoor tracking system is also presented, which integrates the CS-based positioning with a Kalman filter for sequential location estimates. Experimental results on two testbeds show the system achieves better accuracy than other fingerprinting methods, suitable for implementation

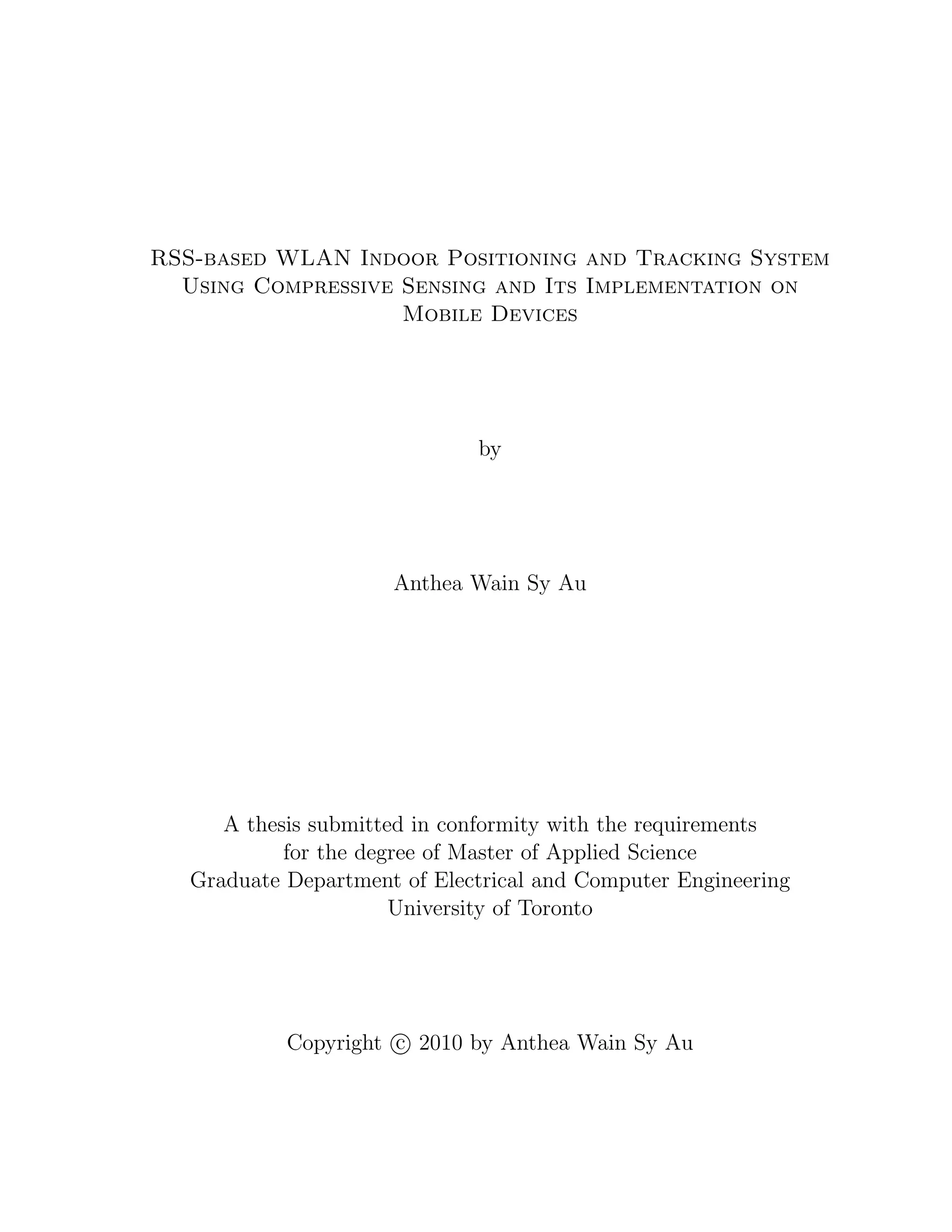

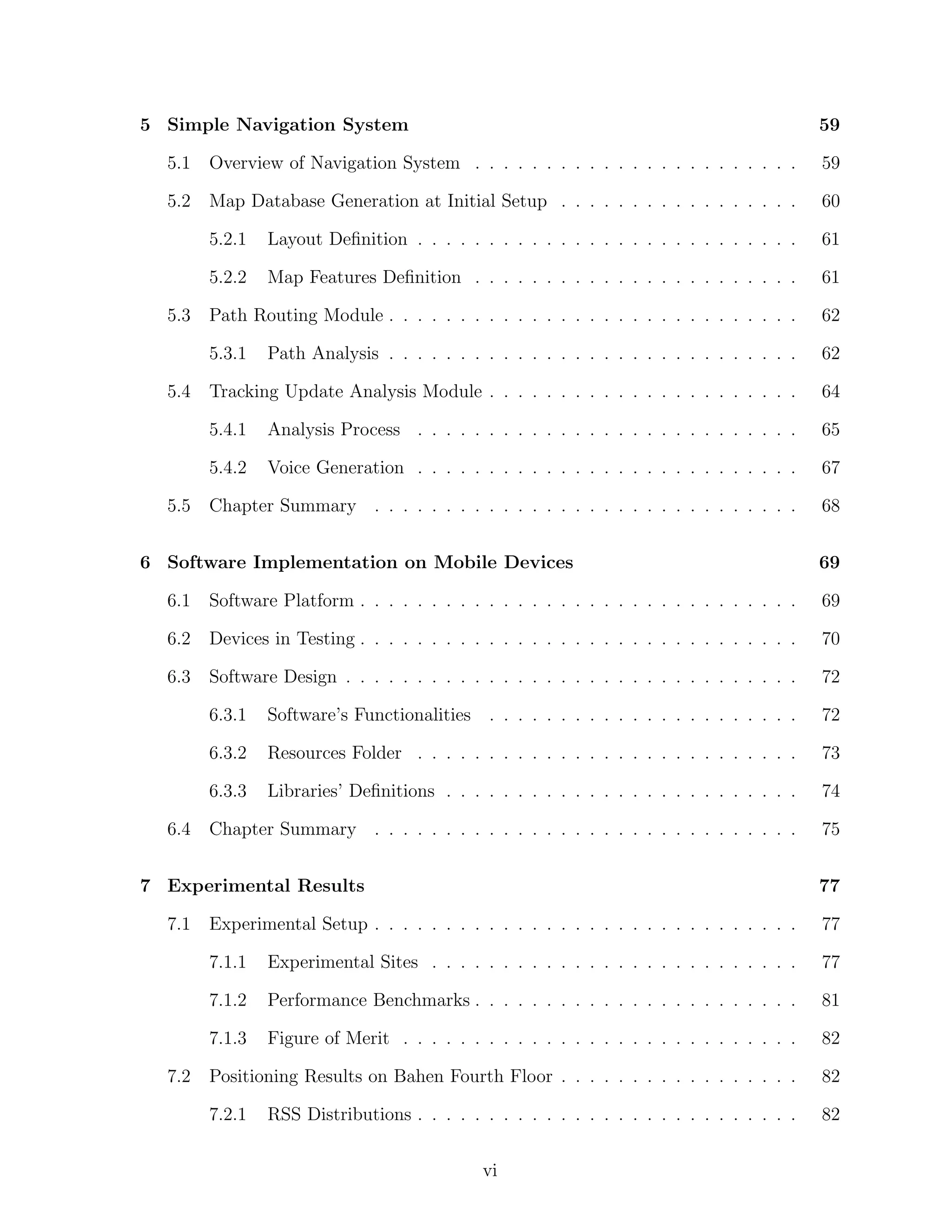

![List of Tables

1.1

Existing RSS-based WLAN Position Systems [1] . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5

1.2

Comparison of a PDA and a laptop . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

8

6.1

Devices Specifications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

70

7.1

Comparison of experimental sites . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

78

7.2

Traces Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

81

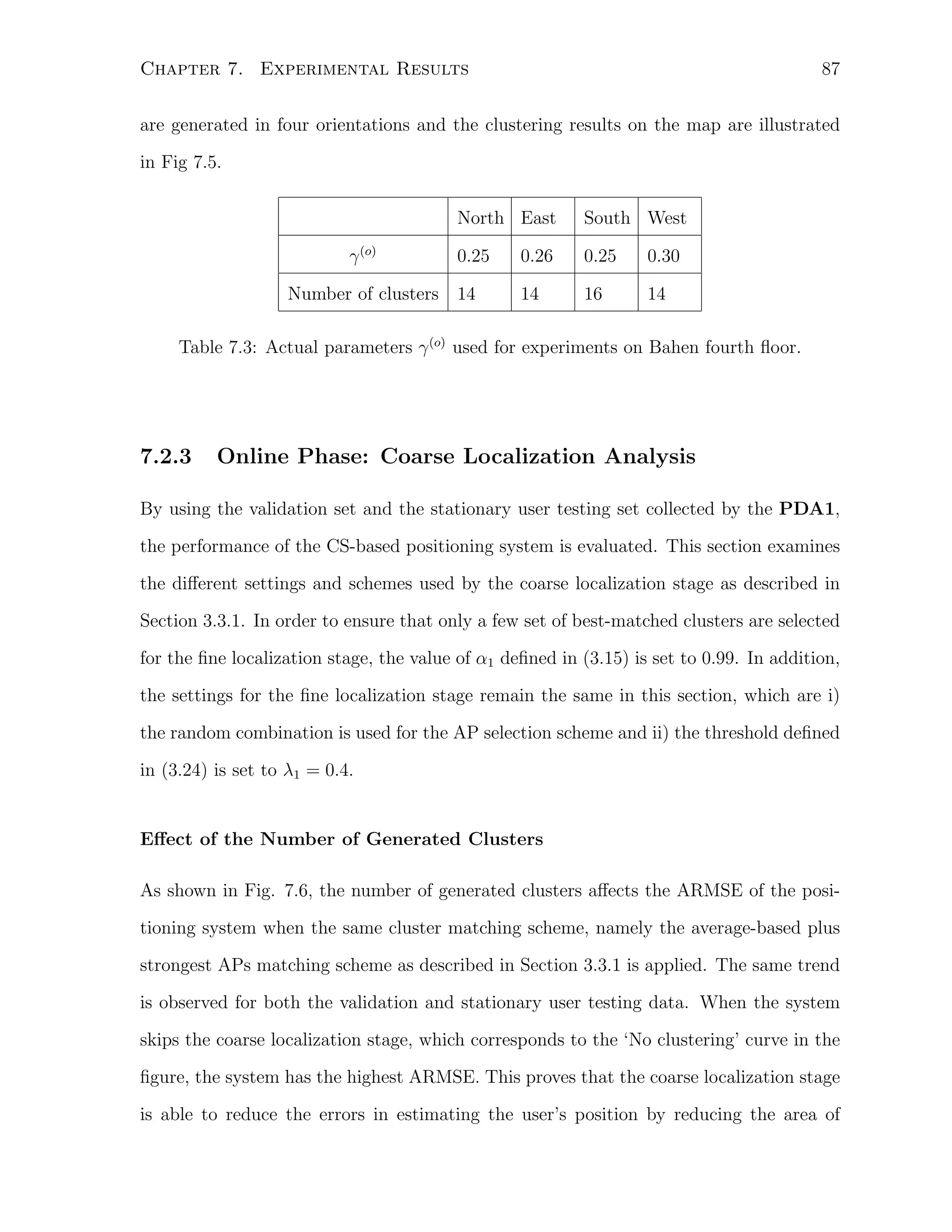

7.3

Actual parameters γ (o) used for experiments on Bahen fourth floor. . . .

87

7.4

A set of optimal parameters for the CS-based position system applied on

Bahen fourth floor. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7.5

Position error statistics for different methods on Bahen fourth floor. (For

validation set) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7.6

94

A set of optimal parameters for the CS-based position system applied on

CNIB second floor. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7.8

94

Position error statistics for different methods on Bahen fourth floor. (For

stationary user testing set) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7.7

93

99

Positioning error statistics for different positioning methods on CNIB second floor. (For mobile user testing set) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

7.9

A set of optimal parameters for the proposed tracking system applied on

CNIB second floor. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

viii](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-8-2048.jpg)

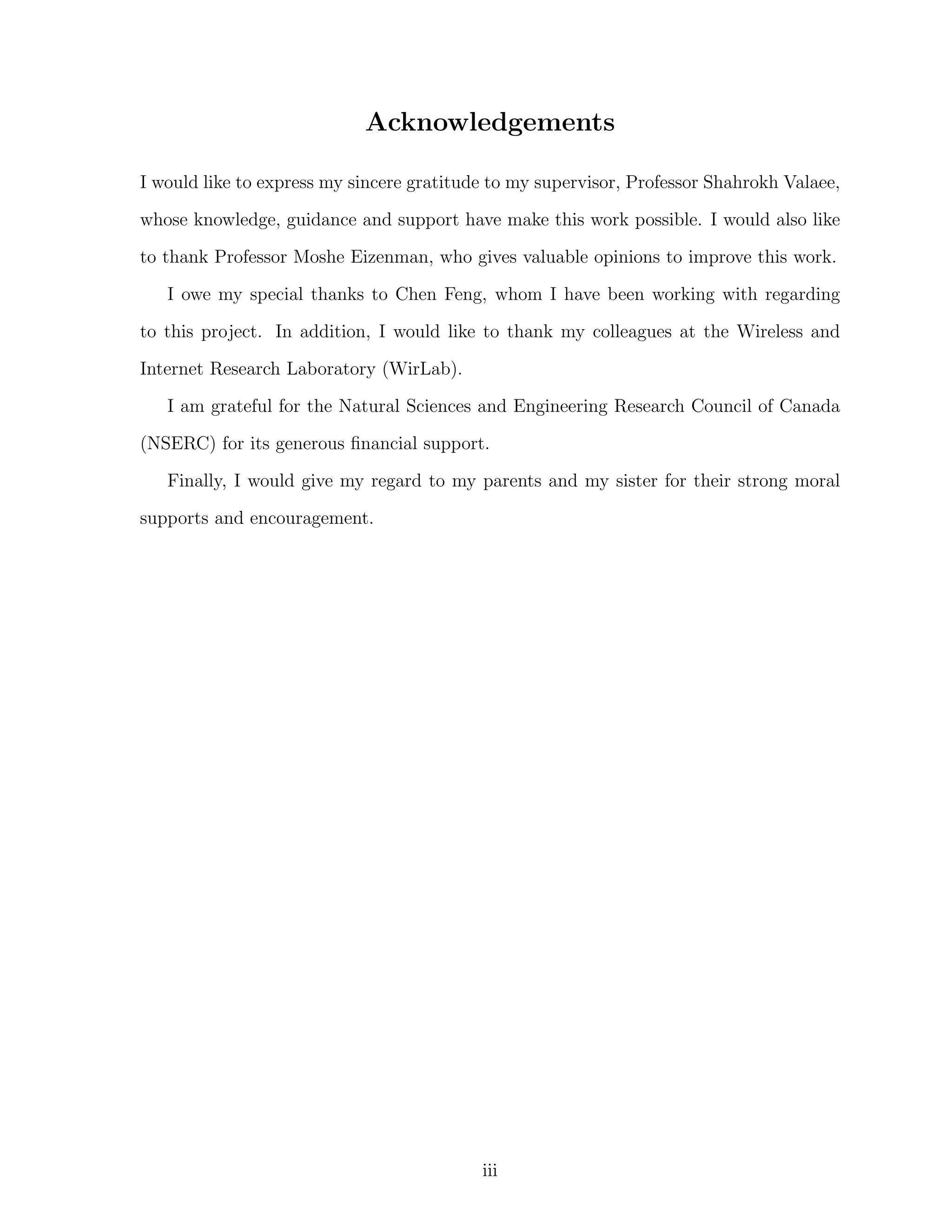

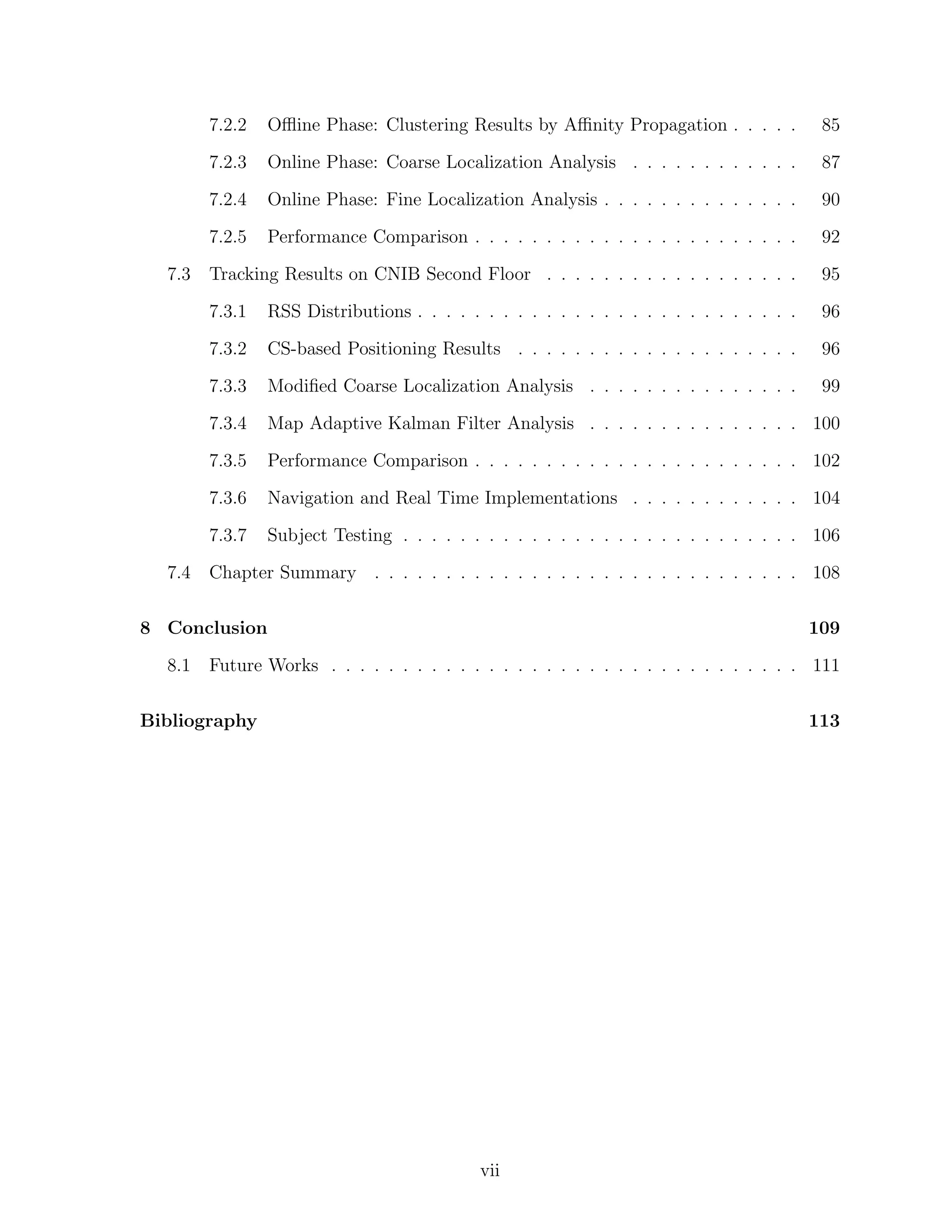

![List of Figures

1.1

The problem setup . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6

2.1

Kernel-based method [2]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

20

3.1

Block diagram of the proposed indoor localization system. . . . . . . . .

29

3.2

Interaction between the database server and the mobile device during offline phase.

3.3

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

34

Interaction between the database server and the mobile device during online phase. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

44

4.1

Block diagram of the proposed indoor tracking system. . . . . . . . . . .

50

4.2

Coarse localization stage for the proposed tracking system. . . . . . . . .

51

4.3

Map-Adoptive Kalman Filter . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

57

5.1

Navigation System Overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

60

5.2

Dijkstra Algorithm . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

63

5.3

Tracking update analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

64

5.4

A point in close range to a line segment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

65

5.5

Determining the direction of turn based on the two line segments ℓi and ℓi+1 67

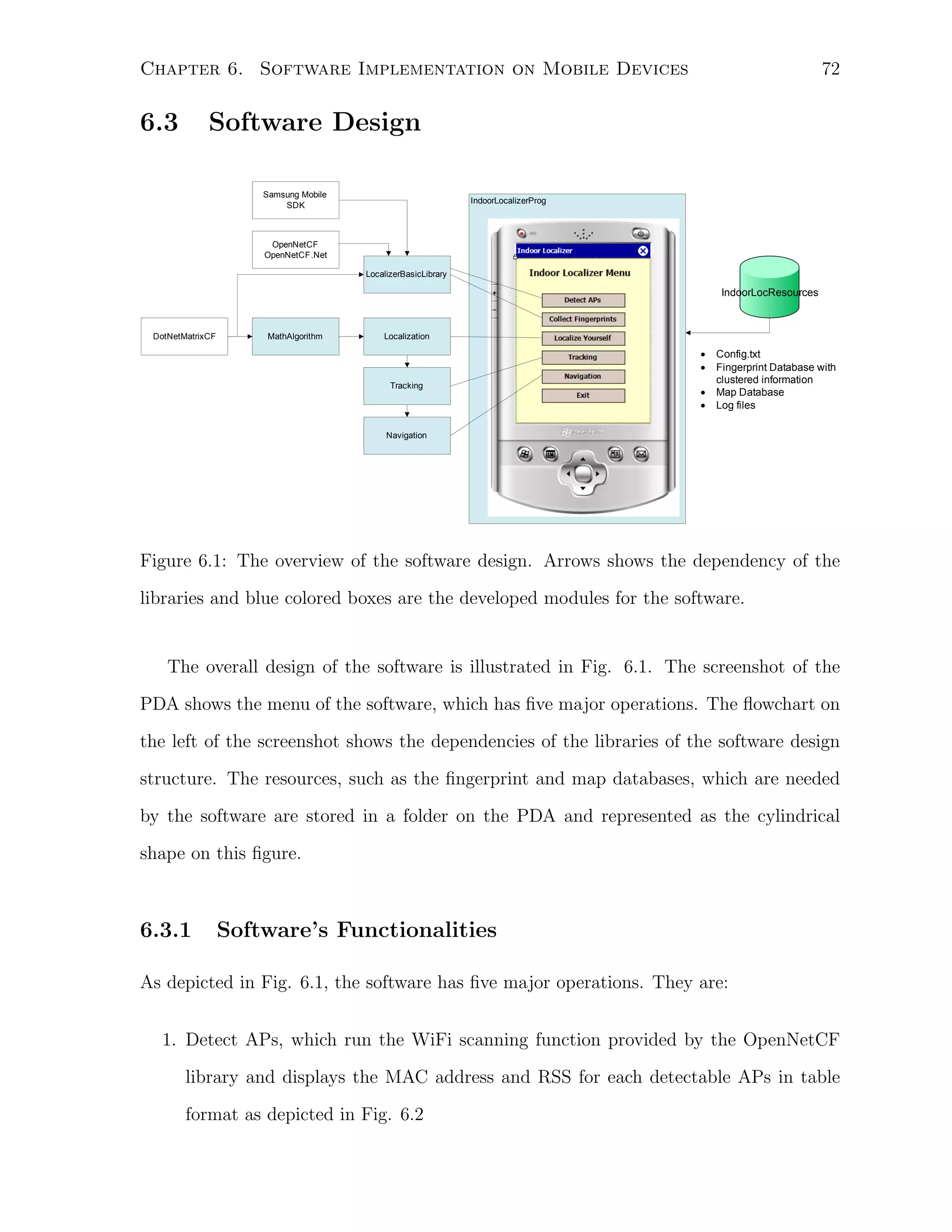

6.1

The overview of the software design. Arrows shows the dependency of the

libraries and blue colored boxes are the developed modules for the software. 72

6.2

An example screenshot of Detect AP operation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

x

73](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-10-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1

Motivation

With the wide deployment of the mobile wireless systems and networks, the locationbased services (LBSs) are made possible on mobile devices, such as laptops, smartphones

and personal digital assistants (PDAs). There are a lot of applications that rely on the

locations of these mobile devices, such as navigation, people and assets tracking, locationbased security and coordination of emergency and maintenance responses to accidents,

interruptions of essential services and disasters, etc [3–5].

In order to deliver reliable LBSs, real-time and accurate user’s locations must be obtained. Hence, there is a growing interest in developing effective positioning and tracking

systems. For the outdoor environment, Global Positioning System (GPS) and cellular

network based systems [3,6,7] are commonly used as the techniques to provide navigation

services. However, these techniques cannot be used directly in indoors, as the signals are

usually too weak to be used for localization purposes. Thus, wireless indoor positioning

has become an increasingly popular research topic in recent years.

There are several methods that are built on top of the GPS-capable phones to provide

indoor localization [8]. One example is the Assisted GPS (A-GPS), which requires a

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-14-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 1. Introduction

2

connection to a network location server in order to obtain the estimated location with

an average of 5-50m accuracy [8]. Another one is the Calibree proposed in [9], which

utilizes the detected signal strength from GSM cell towers to determine relative positions

of mobile phones and their absolute locations can be determined if some of the phones are

equipped with GPS receivers. In addition, indoor localization can also be implemented

on GSM mobile phones [10] and CDMA mobile phones [11] through the use of wide

signal-strength fingerprints. The median errors of these cellular-based system are around

4-5m. Although these methods are able to provide moderately accurate position estimate

in indoors, their accuracies may not be enough to provide reliable LBSs and also they

are only applicable to mobile phones.

Besides the use of GPS and cellular network, different types of wireless technologies

and sensors are also employed for the indoor positioning. In particular, positioning

systems using ultra-wide band (UWB) signals, infrared, radio frequency (RF), proximity

sensors and ultrasound systems [1, 8, 12] are able to localize users with high accuracies.

However, these systems require the installation of additional infrastructures and sensors,

which lead to high budget and labour cost and preventing them from having large-scale

deployments.

Due to the wide deployment of wireless local area network (WLAN), which is specifically referred to as the IEEE 802.11b/g standard in this thesis, there are many indoor

positioning systems that make use of WLAN for estimating user’s position. Time of arrival (TOA) [13] and time difference of arrival (TDOA) [1,14] are two techniques that can

be used for localization, but they require extra configuration and setup to provide valid

measurements. Thus, received signal strength (RSS) is the feature metric used for the

WLAN positioning systems, as it can be obtained directly from existing WLAN access

points (APs) by any device that is equipped with a WLAN network adapter.

This thesis presents an accurate RSS-based WLAN positioning and tracking system

that can be implemented on mobile devices with limited resources. The affinity propa-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-15-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 1. Introduction

3

gation algorithm for clustering data points [15] and the compressive sensing theory for

recovery of the sparse and incoherently sampled signals [16] are two concepts applied on

the proposed system.

1.2

RSS-based WLAN Positioning Systems

The WLAN IEEE 802.11b/g is a standard used for providing wireless internet access for

indoor areas. It is operated at 2.4 GHz Industrial, Scientific and Medical (ISM) band

within a range of 50-100 m. As mentioned earlier, the RSS can be easily obtained by

using any WLAN-integrated device, thus it is used by most of the WLAN positioning

systems.

1.2.1

Location-Sensing Techniques

There are three major techniques to obtain the location estimate from the RSS [8, 17].

They are listed as follows:

1. Triangulation: The RSS can be translated into distance from the particular AP

according to a theoretical or empirical signal propagation model. Then, with distance measurements from at least 3 APs with known positions, lateration can be

performed to estimate the locations. This approach does not give accurate estimate, as the indoor radio propagation channel is highly unpredictable and thus the

use of the propagation model is not reliable.

2. Proximity: This method finds the strongest RSS from a specific AP and determines

the location to be the region covered by this AP. This method only gives a very

rough position estimate but it is easy to be implemented.

3. Scene Analysis: This method first collects RSS readings at known positions, which

are referred to as fingerprints, in the area of interest. Then, it estimates the loca-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-16-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 1. Introduction

4

tions by comparing the online measurements with the fingerprints through pattern

recognition techniques. This method is used by most WLAN positioning systems,

as it is able to compute accurate location estimates. This is the approach used by

the positioning and tracking system proposed in this thesis.

1.2.2

Existing Positioning Systems

Table 1.1 summarizes some of the existing WLAN positioning systems that can be accessible to the public. It shows that the use of fingerprinting achieves the best accuracy

in indoor areas. Although the Ekahau [18] attains the best accuracy, it uses the the

probabilistic method to compute the estimated positions and thus requires a more comprehensive survey of RSS readings in the region of interest. In addition, its position

calculation is computed at the server as the complexity of the probabilistic method is

too high to be performed on the mobile devices. This raises additional issues when using

this systems. First, the devices must be connected to the same network as the server to

obtain position estimates. Second, positions obtained from the server must be encrypted

before it is transmitted to the mobile devices, in order to protect the privacy of the users.

The aim of this thesis is to design an indoor positioning and tracking system that

can provide accurate position estimate with relatively low computational complexity, so

that it can be computed on mobile devices. This solution may have a database server

to keep track of the fingerprints database collected, but once downloaded to the devices,

they are no longer required to be connected to the server to obtain position estimates.

This system is more flexible and has no privacy concerns to the users.

1.3

Problem Statement and Objectives

A typical WLAN indoor tracking scenario as illustrated in Fig. 1.1 consists of 1) a

mobile device equipped with a WLAN adapter, which is carried by a user and collects](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-17-2048.jpg)

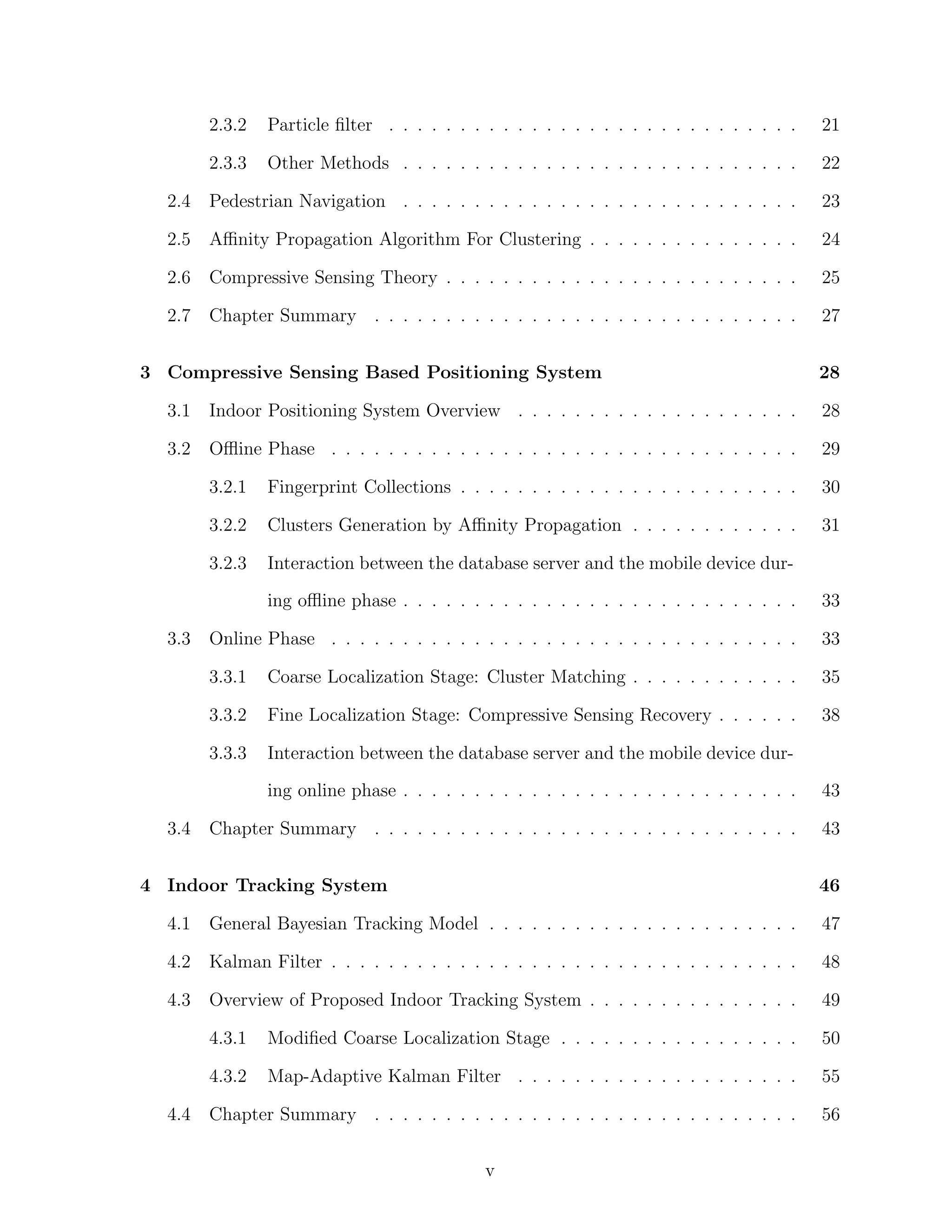

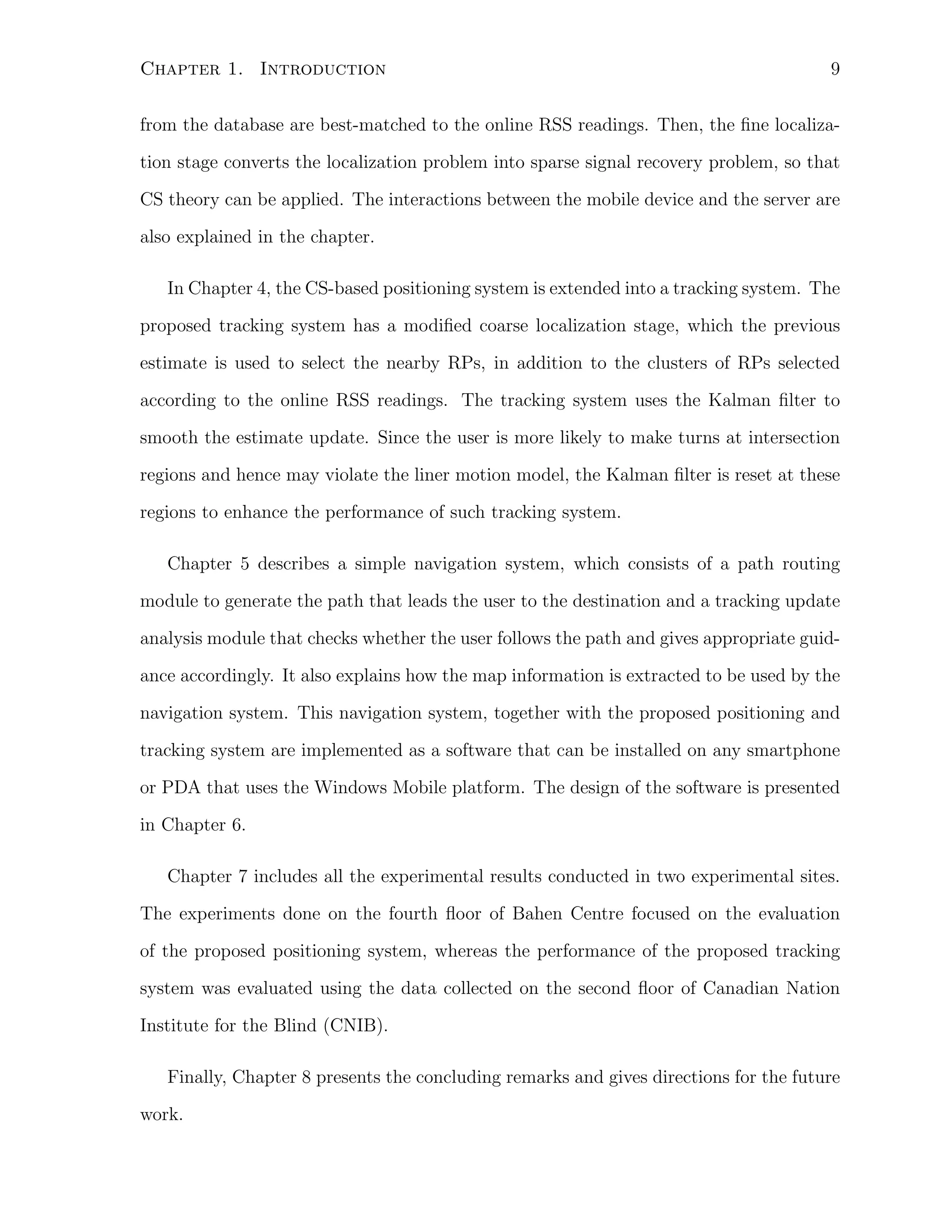

![5

Chapter 1. Introduction

Microsoft

Research Ekahau [18]

RADAR [19, 20]

Inter Place Lab and

Skyhook’s WPS [21]

Range

Building/local area

Building/local area

Position

Mobile device

Server (Ekahau Posi- Mobile device

Calculation

Metropolitan area

tioning Engine)

Position

Fingerprinting

+ Fingerprinting

+ Map-based pinpoint-

Method

KNN + Viterbi-like probabilistic

ing (obtain APs data

algorithm

by war driving) and

triangulation

Accuracy

3-5m

1-3m

20+ m

Table 1.1: Existing RSS-based WLAN Position Systems [1]

RSS from detectable access points for localization; 2) access points (APs), which can be

commonly found in most buildings and their exact positions are not necessarily known

to the localization systems, as they may belong to different network groups and possibly

3) a database server, which stores the fingerprints collected by the mobile device. The

WLAN-enabled device can extract information, such as MAC address, SSID and received

signal strength (RSS) about these APs by receiving messages broadcasted from them.

This thesis focuses on the WLAN localization and tracking problem using RSS as the

measurement metric. The mobile device carried by the user collects the RSS from L

different APs whose unique MAC addresses are used for identification. Then, the system

determines the current position based on this RSS measurements and previously collected

fingerprint database.

The goal of this thesis is to propose a real-time WLAN positioning and tracking system

that can give accurate position estimate and can be implemented on mobile devices, so

that LBSs can be applied. In the context of this thesis, the mobile devices refer to the

handheld devices, such as personal digital assistants (PDAs) and smartphones, which](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-18-2048.jpg)

![6

Chapter 1. Introduction

Reference Point

WLAN

Access Point

User equipped with

mobile device

Database Server

000

Figure 1.1: The problem setup

have degraded WLAN antennas, limited power, memory and computation capabilities,

thus a light-weight algorithm is required to allow these devices to have real-time and

accurate performance.

The localization problem is defined as follow. First, the device collects online RSS

readings from available APs periodically at a time interval ∆t, which is limited by the

device’s network card and hardware performances. These online RSS readings can be

denoted as r(t) = [r1 (t), r2 (t), . . . , rL (t)], t = 0, 1, 2, ..., where rl (t) refer to the RSS

reading collected from AP l at time t. Then, the proposed positioning and tracking

system uses r(t) to compute the position estimate, denoted as p(t) = [ˆ(t), y (t)]T , where

ˆ

x

ˆ

(ˆ(t), y (t)) are the Cartesian coordinates of the estimated position at time t.

x

ˆ

1.4

Technical Challenges

The unpredictable variation of RSS in the indoor environment is the major technical

challenge for the RSS-based WLAN positioning systems. There are four main reasons

that lead to the variation of RSS. First, due to the structures of the indoor environment

and the presence of different obstacles, such as walls and doors, etc, the WLAN signals

experience severe multi-path and fading and the RSS varies over time even at the same

location. Secondly, since the WLAN uses the licensed-free frequency band of 2.4GHz,

the interference on this band can be very large. Example sources of interference are the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-19-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 1. Introduction

7

cordless phones, BlueTooth devices and microwave. Moreover, the presence of human

bodies also affects the RSS by absorbing the signals [22], as human bodies contain large

amount of water, which has the same resonance frequency as the WLAN. Finally, the

orientation of the measuring devices also affects the RSS, as orientation of antenna affects

the antenna gain and the signal is not isotropic in real indoor environment.

All of the above reasons make it infeasible to find a good radio propagation model

to describe the RSS-position relationship. Thus, a fingerprinting method is often used

instead to characterize the RSS-position relationship. This method computes the position

estimate by matching the online RSS readings to the fingerprints collected during training

phase. This pattern matching process is a non-trivial problem as there are derivations

between the online RSS readings to the fingerprint RSS readings due to the time-varying

characteristics of the indoor radio propagation channel. In addition, the movement of

objects, including the movement of the user who carries the mobile device, also affects

the RSS readings. This type of variation of RSS is needed to be addressed by the

fingerprinting-based positioning systems, in order to provide accurate position estimate.

Another challenge relates to the computational capabilities of the mobile devices.

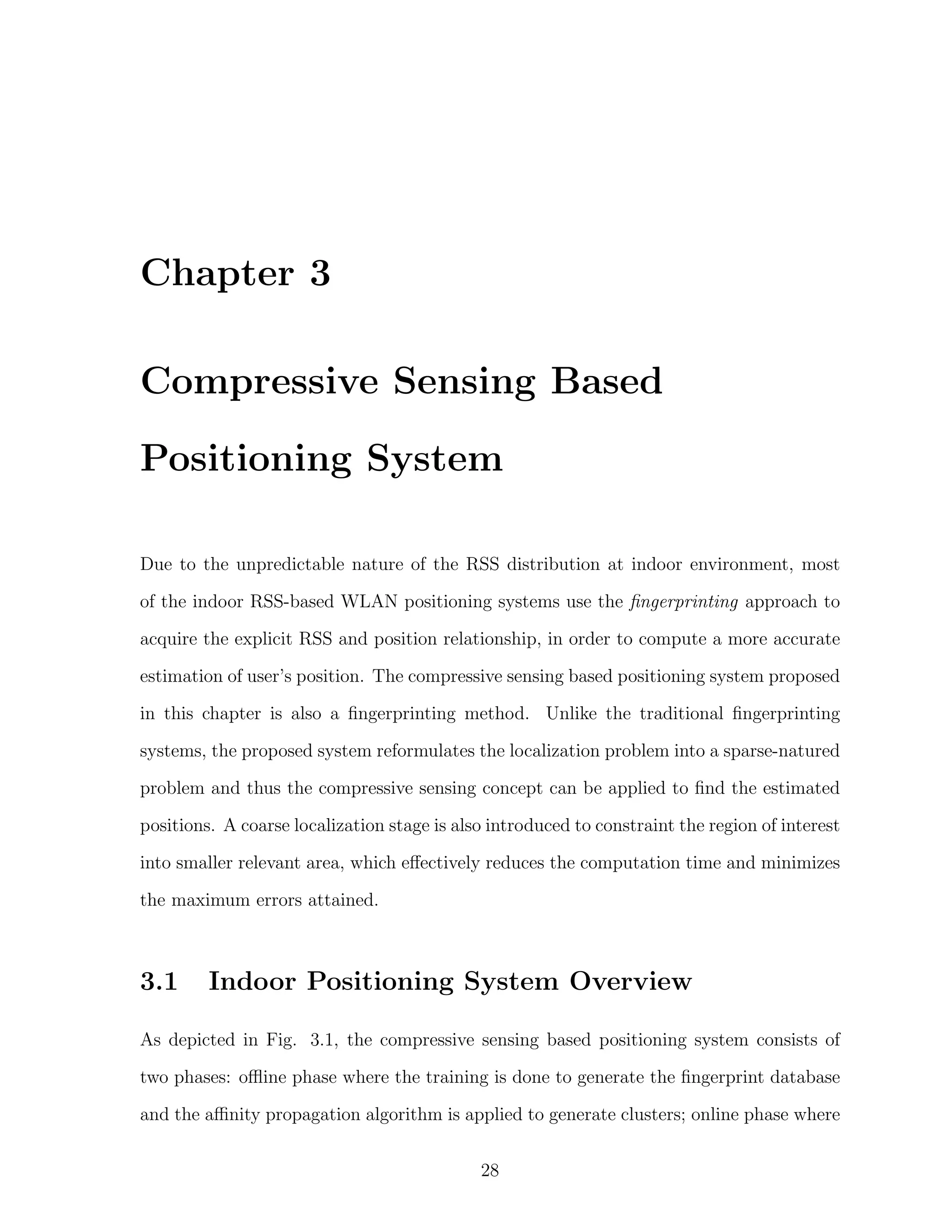

Table 1.2 compares the processor speed and memory equipped by a PDA, which is used

in this thesis to evaluate the performance of the proposed positioning system and a

labtop with average performance. It shows that the PDA has very limited computation

speed and memory when comparing to the labtop. Thus, some of the positioning systems

that can be implemented on the laptop may not be able to be used by the PDA. The

computational complexity and the use of memory must be taken into consideration when

designing the positioning and tracking systems in this thesis.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-20-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 1. Introduction

1.6

10

Contributions

This thesis proposes and implements a two stages indoor RSS-based WLAN positioning, tracking and navigation system using compressive sensing, clustering and filtering

techniques. Here are the list of contribution, including the chapters presenting them and

publications referring to them:

1. Compressive sensing based positioning system: This positioning system applies the affinity propagation algorithm on the collected fingerprint database to

generate clusters of RPs, which have similar RSS values and are geographically

close to each other. Then, such system uses the coarse localization stage to choose

the relevant clusters of RPs, based on the online RSS measurement. Finally, the localization problem is translated into a sparse signal problem, so that the estimated

position can be computed by solving a ℓ1 norm minimization problem according to

the compressive sensing theory. (Chapter 3 and [23, 24])

2. Tracking system: The CS-based positioning system can be easily extended to

include the previous position estimate and the map information to improve its

performance. The tracking system has a modified coarse localization stage. In

addition to the clusters of RPs selected based on the online RSS measurements,

RPs which are physically close to the previous position estimate are also chosen

and the common RPs found in both sets are used in the fine localization stage. The

computed estimate is then post-processed by the Kalman filter. This filter is reset

when the estimate is at the intersection regions, as the user may make turns and

violate the liner motion model used by the Kalman filter. (Chapter 4)

3. Navigation system: A simple navigation system, which uses the map database

to generate path to destination using Dijkstra algorithm and gives guidance, is developed. It also determines whether the user follows the path and gives appropriate

instructions at proper times. (Chapter 5).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-23-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 1. Introduction

11

4. Software implementation and performance evaluation: A software is developed to implement the proposed positioning and tracking system, as well as a

simple navigation system. It is written in C# and can be installed on any smartphone or PDA that uses Windows Mobile as its operating system. This software

can give real-time position updates and also navigation guidance to the user. The

performance evaluations of the proposed positioning and tracking system are done

for two different experimental sites: Bahen centre and CNIB. Experimental results

show that these systems are able to provide good position estimate of the user

and can be implemented on the PDAs with limited resources, to give real-time

performance. (Chapter 6 and 7 and [23, 24]).

This project is a joint work with Chen Feng, a visiting PhD student from the Beijing Jiaotong University, at the Wireless and Internet Research Laboratory (WirLab),

supervised by Professor Shahrokh Valaee. We work closely together to implement the

indoor tracking and navigation system on the handheld devices. Chen focuses more on

the compressive sensing based positioning system, while I focus more on the tracking and

navigation system, as well as the software implementation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-24-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 2

Background and Related Works

In this section, a brief overview of RSS-based WLAN positioning and tracking techniques

is given. The two fingerprinting-based methods, namely KNN and Kernel-based are

summarized in Sections 2.2.1 and 2.2.2, as they are implemented in Chapter 7 to compare

the performance of the proposed positioning system. In addition, some works about

pedestrian navigation are summarized.

There are two additional concepts used by this thesis to develop the proposed positioning and tracking system using the fingerprinting approach. Section 2.5 describes the

operation of the affinity propagation algorithm, which generates clusters of similar data

points. Section 2.6 summarizes the compressive sensing theory which can be applied on

the localization problem to estimate the user’s location.

2.1

Indoor RSS-based WLAN Positioning Techniques

The key problem for the indoor RSS-based positioning systems is to identify the RSSposition relationship, so that the user’s location can be estimated based on the RSS

collected at that location. There are two approaches in dealing with this relationship [25]:

the uses of signal propagation models [26, 27] and the location fingerprinting methods

[2, 19, 28].

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-25-2048.jpg)

![13

Chapter 2. Background and Related Works

2.1.1

Signal Propagation Modeling

This technique uses the RSS readings collected by the mobile device to estimate the

distances of the device from at least three APs, whose locations are known, based on

a signal radio propagation model. Then triangulation is used to obtain the device’s

position [8].

The accuracy of this technique depends heavily on finding a good model that can

best describe the behavior of the radio propagation channel. However, the indoor radio

propagation channel is highly unpredictable and time-varying, due to severe multipath

in indoor environment; shadowing effect arising from reflection, refraction and scattering

caused by obstacles and walls; and interference with other devices operated at the same

frequency (2.4GHz) as the IEEE 802.11b/g WLAN standard, such as cordless phones,

microwaves and BlueTooth devices. There are two models that are often used for the

indoor radio propagation channel:

• Combined model of path loss and shadowing [29]

This model combines the simplified path-loss model with the effect of shadowing,

which is assumed to be a log-normal random process. The received power pr which

is d meters away from a specific AP is given by:

pr [dBm] = p0 [dBm] + 10 log10 K − 10γ log10

d

− ηdB

d0

(2.1)

where K is a constant depending on the antenna characteristics and channel attenuation, p0 is the signal power at a reference distance d0 for the antenna far field,

γ is the path-loss exponent, which varies for different surrounding environments

2

(2 ≤ γ ≤ 6 for indoor environment) and ηdB ∼ N (0, ση ) is a Gaussian random

variable.

• Wall Attenuation Factor model [19]

This model includes the effects of obstacles or walls between the transmitter and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-26-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 2. Background and Related Works

receiver. The received power can be obtained by:

nW · W AF nW < C

d

pr [dBm] = p0 [dBm] − 10γ log10

−

d0 C · W AF

nW ≥ C

14

(2.2)

where nW is the number of obstacles or walls between the transmitter and receiver,

C is a threshold up to which no significant attenuation can be observed and W AF

is the wall attenuation factor.

The two empirical models require the calibration of the parameters, such as the path

loss exponent, which vary depending on different environments. This often requires a

comprehensive survey of the RSS distributions over the environment, which is a time

consuming process. In addition, the models assume the RSS is distributed isotropically

from the transmitter. This is often not the case for indoor environments due to the

presence of obstacles. The orientation of the antenna of the mobile device also affects

the RSS [22], but it is not reflected in the two models. Finally, the locations of the APs

may not be known in the real scenario, as these APs may be installed and owned by

different vendors. All of these make the models inadequate to describe the RSS-position

relationship in real situation and lead to errors in estimating the user’s location.

2.1.2

Location Fingerprinting

A location fingerprinting method is often used instead of the radio propagation model,

as it can give better estimates of the user’s locations for indoor environments. This

method is divided into two phases: offline and online phases. During the offline phase,

which is also referred to as the training phase, the RSS readings from different APs are

collected by the WLAN-integrated mobile device at known positions, which are referred

to as the reference points (RPs) to create a fingerprint database, also known as the radio

map. Since the orientation of the device’s antenna affects the RSS readings, a more

comprehensive fingerprint database can be built by collecting RSS readings for different](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-27-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 2. Background and Related Works

15

orientations at the same RP. The actual positioning takes place in the online phase. The

mobile device, which is carried by the user collects RSS readings from different APs at an

unknown position. Then, these RSS online measurements are compared to the fingerprint

database to estimate the user’s location by using different methods described in the next

section.

The accuracy of the estimated position of the user depends highly on the number of

RPs collected in the fingerprint database. If there are more RPs, then the radio map

has a finer resolution and thus allows a better estimation [28]. In addition, since the

RSS varies over time, collecting more time samples of RSS readings at the same RP also

improves the position estimation. Thus, this fingerprint database collection is a time

consuming and labour-intensive process. [30] uses the spatial correlation of adjacent RPs

to generate the database by interpolation from a small number of RPs and this method

is able to reduce the labour effort and time required for the offline phase.

Another disadvantage of this fingerprinting approach is the maintenance of such

databases. Since the RSS propagation environment varies with time, the accuracy of

using the database degenerates over time, as the current RSS readings slowly deviate

from the readings in the database. The database may even be rendered useless, if the

environment changes significantly. This requires the fingerprint database to be rebuilt

periodically, in order to ensure the accuracy of the positioning system. [31] presents a

novel method to update the radio map using the online RSS readings, which can efficiently update the fingerprint database without the labour and time overhead cost as

required by rebuilding such database from scratch.

As shown in [32], the RSS readings collected by different network cards are different,

which can vary up to -25dBm. This indicates that the same fingerprint database cannot

be used by different mobile devices, which are equipped with different WLAN network

cards. That means that the fingerprint collection process must be done on each device

and lead to very high labour and time costs. Another method is to use the signal strength](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-28-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 2. Background and Related Works

16

difference (SSD) between APs instead of the RSS as the fingerprint [33].

Although there are limitations to the location fingerprinting, it is a simple and effective

method to be used by indoor positioning systems. This thesis also uses this approach to

estimate the user’s location.

2.2

Fingerprinting-Based Positioning Methods

There are two approaches to estimate the user’s location based on the online RSS measurements and the fingerprint database [34, 35]. The deterministic approach only uses

the average of the RSS time samples from each RP to estimate the location, whereas the

probabilistic approach incorporates all the RSS time samples for the computation.

For the following section, assume the collected fingerprint database is denoted as a

set {(pi , ψ i (1), . . . , ψ i (T ))|i = 1, . . . , N }, where pi is the Cartesian coordinates for RP

i, ψ i (t) = [ψi,1 (t), . . . , ψi,L (t)]T is the RSS readings vector for RP i at time t with ψi,j (t)

denoted as the RSS reading from AP j for RP i at time t. T is the total number of

collected time samples, N is the total number of RPs and L is the total number of APs.

The online RSS measurement vector can be denoted as r = [r1 , ...rL ]T .

2.2.1

K-Nearest Neighbour Method (KNN)

The K-nearest neighbour (KNN) method is a deterministic approach that uses the average

of the RSS time samples of RPs from the fingerprint database to estimate the user’s

location [19]. It first examines the Euclidean distance of the online RSS measurement

vector to the RPs in the database, namely:

¯

Di = ∥r − ψ i ∥

¯

where ψ i =

1

T

∑T

τ =1

(2.3)

ψi,1 (τ ) is the average RSS vector for RP i. Then, the distances

are sorted in ascending order and the first K RPs that have the smallest distances are](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-29-2048.jpg)

![17

Chapter 2. Background and Related Works

obtained to estimate the location p:

ˆ

K

1 ∑

p

p=

ˆ

K i=1 i

(2.4)

The calculated distances can be used as weights to estimate the location and it is referred

to as the weighted-KNN. The estimated location can be found by

∑K 1

pi

i=1

p = ∑K Di1

ˆ

(2.5)

i=1 Di

2.2.2

Probabilistic Approach

The location estimation problem can be solved by using probabilistic models [2, 36, 37,

37, 38]. The core concept is to find the posterior distribution of the location, which is

the conditional probability p(pi |r) [37]. This conditional probability can be estimated

by using the Maximum A Posteriori (MAP) estimator, which is derived from Bayes rule.

That is:

pM AP = arg max f (pi |r) = arg max

ˆ

pi

pi

f (r|pi )f (pi )

N

∑

(2.6)

f (r|pi )f (pi )

i=1

where f (pi |r) and f (r|pi ) are the conditional probability density functions. Note that

the denominator of (2.6) can be safely ignored as it remains the same regardless of the

choice of pi . In general, there is no prior knowledge of the device’s location and thus

the prior density f (pi ) is assumed to be uniform, which transforms this MAP estimation

into a Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation:

pM L = arg max f (r|pi )

ˆ

(2.7)

pi

The estimation can be further improved by including the likelihood densities as the weight

for the K RPs with the highest likelihood densities, namely:

pM L+weight =

ˆ

K

∑

wi p i

(2.8)

i=1

f (r|pi )

wi = ∑K

j=1 f (r|pi )

(2.9)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-30-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 2. Background and Related Works

18

There are several methods to estimate the likelihood density functions f (r|pi ), i =

1, . . . , N from the fingerprint database. Two of the common methods are reviewed here.

Both of them assume that the RSS from different APs are uncorrelated and independent,

∏

so that the density function can be simplified to f (r|pi ) = L f (rk |pi ).

k=1

Histogram

The likelihood density functions can be estimated by the histogram method. This method

requires two parameters to generate a histogram for the RSS time samples collected for

each of the AP at each of the RP [37]. The first parameter is the number of bins,

which are a set of non-overlapping intervals that cover the whole possible range of the

RSS values. The second is the origin of the bins, which is necessary to determine the

boundaries of the bins. Then, the likelihood density estimate for a particular RSS value

can be obtained as the relative frequency of the bin, which contains that particular RSS

value [37].

There are several drawbacks for this method. First, the likelihood density estimate

depends heavily on the choice of the origin and the bin width and thus careful experimental calibration of these parameters is required [37]. Second, a large amount of RSS

samples for each RP is required to generate a reliable histogram that produces good

location estimate.

Kernel-Based

Instead of using the histogram, the kernel-based method uses the kernel density estimator

to estimate the density functions [2,37]. The density function can be estimated as follows:

T

∑

ˆ(r|p ) = 1

f

K(r; ψ i )

i

T t=1

(2.10)

where K(r; ψ i ) denotes the kernel function. A common choice of the kernel function is

the Gaussian kernel. By assuming that the RSS from different APs are uncorrelated and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-31-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 2. Background and Related Works

19

independent, the Gaussian kernel function is defined as:

)

(

1

∥r − ψ i (t)∥2

K(r; ψ i ) = √

exp −

∗

∗

2(σi )2

( 2πσi )L

(2.11)

∗

where σi is the kernel bandwidth. The determination of this kernel bandwidth is evalu-

ated in [2]. Since this method takes all the RSS time samples collected at each RP into

account for estimating the likelihood densities, the computation time is much larger than

the KNN method.

In this thesis, the kernel-based method is also implemented to compare its performance to the proposed positioning system. The operation of the method using the

Gaussian kernel is summarized in Fig. 2.1 [38].

2.2.3

Region of Interest and Access Points Selections

Before applying the above methods on the whole fingerprint database to estimate the

user’s location, two pre-processing steps can be introduced to confine the localization

problem into a subset of relevant RPs and a subset of APs, which can distinguish the

RPs easily. The region of interest determination step is able to mitigate the effect of the

deviations between the online readings and the radio map due to the time-varying characteristic of the indoor radio channel [39]. In addition, the purpose of AP selection step

is to remove extra APs that may lead to biased estimations and redundant computations,

which is often the case as APs are widely deployed in indoor buildings [38].

Both steps are often carried out together as the reliability of the APs varies for

different RPs [36, 38, 39]. The joint clustering technique proposed in [39] selects the

strongest m APs to generate the probability distribution for each RPs and groups the

RPs, which have the same q strongest APs list, as a cluster during offline phase. The

argument of using strongest APs is that they provide the highest probability of coverage

over time [39]. However, they may not be a good choice, as the variation of the APs may

also lead to error in estimation [28]. [40] presents another AP selection criterion that is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-32-2048.jpg)

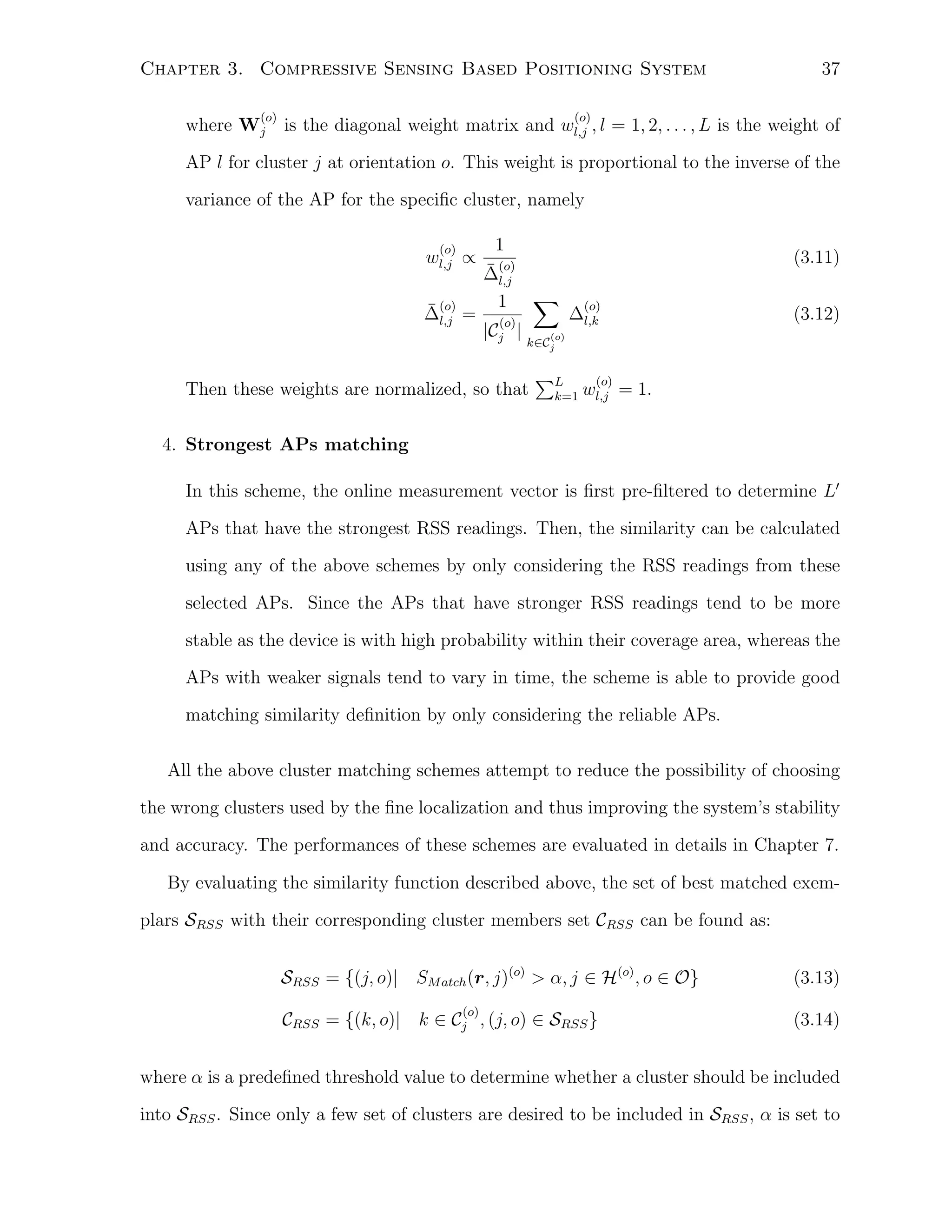

![20

Chapter 2. Background and Related Works

Given:

Radio Map: {(pi , ψ i (1), . . . , ψ i (T ))|i = 1, . . . , N }

Number of APs: L

Number of time samples: T

Inputs:

Online RSS measurement vector: r

Outputs:

Position estimate: p

ˆ

Kernel-based Method:

∗

Optimal bandwidth: σi

( 4 ) 1

−1

∗

σi = L+2 L+4 σi T L+4

ˆ

∑

1

l

where, σi = L L (ˆi )2

ˆ2

l=1 σ

(ˆi )2 =

σl

1

T −1

∑T

t=1 (ψi,l (t)

¯

− ψi,l )2 ,

¯

ψi,l =

1

T

∑T

t=1

ψi,j (t)

Weight calculation:

)

(

∑

2

1

i

wi = T (√2πσ∗ )L T exp − ∥r−ψ∗(t)∥

t=1

2(σ )2

i

i

Estimation:

p=

ˆ

∑N

i=1 wi pi

∑N

i=1 wi

Figure 2.1: Kernel-based method [2].

based on AP’s discrimination power in terms of entropy calculations. Several more AP

selection schemes and the use of spatial filtering for region of interest determination can

be found in [2].

This thesis uses the affinity propagation algorithm to generate cluster of RPs with

similar RSS readings during offline phase. Then, a coarse localization stage is introduced

in online phase to identify in which cluster of RPs should the user be located. In addition,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-33-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 2. Background and Related Works

21

different AP selection schemes are also explored for the proposed positioning system.

2.3

Indoor Tracking

Most of the indoor tracking methods use past position estimates and pedestrian motion

dynamics to refine the current position estimate determined by the above positioning

methods. In addition, the dynamic motion model can also be used in conjunction with

the current position estimate to predict the future possible locations. The pedestrian

motion dynamics can be modeled by a general Bayesian tracking model and a filter

is then derived to refine the position estimates [41]. There are two filters that are used

commonly to improve the accuracy of positioning systems [41]: Kalman filter and Particle

filter.

2.3.1

Kalman filter

By assuming the Gaussian tracking noise model and linear motion dynamics, the general

filter becomes a Kalman filter, whose optimal solution is a minimum mean square error

(MMSE) estimate. Although the assumption of Gaussian RSS-position relationship is

not often the case [22], the application of the Kalman filter as the post-processing step

is able to improve the accuracy of the positioning systems [41–44]. The parameters of

the Kalman filter are needed to be found experimentally. [45] provides some guidelines

on how to set the parameters for each update steps based on the map information.

2.3.2

Particle filter

The particle filter is a sequential Monte Carlo method that generates random samples,

known as particles, according to a motion models and estimates their probability densities

[46, 47]. Unlike the Kalman filter, the particle filter can be applied on non-Gaussian and

non-linear models. In addition, map information can be used to further improve the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-34-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 2. Background and Related Works

22

performance of the particle filter by assigning zero weights to the invalid particles, such as

those across the wall [48,49]. Backtracking based on the map information is also proposed

in [50]. Moreover, information obtained from accelerometers and inertial measurement

units (IMU) can also be used to refine the motion models and let the filter to generate

particles that are more relevant and hence improve the tracking accuracy [51, 52].

However, the major drawback of the particle filter is its high computation complexity.

For example, 1600 particles are needed for each filter update for a 40m×40m experimental

area to achieve the best performance [49]. This large computation workload can not be

handled by the mobile devices to give real-time updates to the user. Hence, this thesis

chooses the Kalman filter to post-process the estimates instead of the particle filter, which

may severely hinder the operations of the mobile devices.

2.3.3

Other Methods

Besides the use of the above filters, several other methods are also used for the indoor

tracking. The Horus positioning system [36] smooths out the resulting location estimate

by simply averaging the last W location estimates obtained by the discrete-space estimator. Liao et al. proposed a method to predict the user’s orientation, which is then

used for the next position estimate to improve the accuracy, from the previously computed location estimates [53]. A Viterbi-like algorithm, which is developed to enhance

the RADAR system [20] and is also implemented by [54], makes use of historical data

based on the KNN method to determine the location estimates. Finally, a nonparametric information filter based on the kernel-based probabilistic method is proposed in [55].

This filter, whose computational complexity is lower than particle filter, is able to deal

with tracking scenarios where Kalman filter is inapplicable.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-35-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 2. Background and Related Works

2.4

23

Pedestrian Navigation

Indoor navigation for pedestrian is different from the vehicular navigation using GPS,

which becomes an essential tool to the driver. Gilli`ron and Merminod [56] describes

e

how to implement the personal navigation system for indoor applications. It is crucial to

extract information from the indoor maps as topological models and node/link models,

so that they can be used for implementation of route guidance. They also implement

map matching algorithms, so that the system can self-correct the user’s locations due

to bad estimates based on the topological elements from the map databases, traveled

distances and direction changes. [48] also describes how the map information can be used

for indoor location-aware systems. There are different ways to present the guidance information graphically to the users based on different output devices and they are explored

in [57]. The experience of using the indoor navigation systems can be enhanced in a

smart environment, which is equipped with different kinds of sensors that can convey

additional information to users [58].

There are more restrictions for the navigation systems when they are targeted to visually impaired users. [59] describes the path planning and following algorithms specifically

designed for visually impaired. In summary, such systems generate obstacle-free paths;

provide more detailed information about the surrounding area and give the guidance in

relation to special objects, such as walls, doors and rails, etc. In addition to the commonly used Dijkstra algorithm to generate the routes [56], a cactus tree-based algorithm

is also used to generate a high-level guidance. A more detailed development of an indoor

routing algorithm for the blind and its comparison to the one for the sighted can be found

in [60].

This thesis develops a simple navigation system, which uses the proposed tracking

system to provide updates of user’s locations. Such system is implemented as a software on PDAs and smartphones and is given to the visually impaired people to test its

usefulness in helping them to get familiar with the indoor environment.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-36-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 2. Background and Related Works

2.5

24

Affinity Propagation Algorithm For Clustering

In this thesis, the affinity propagation algorithm described in [15] is used to cluster the

RPs with similar RSS readings, so that the proposed positioning and tracking system is

able to confine the localization problem into a smaller region.

Unlike the traditional K-means clustering method, which may lead to bad clustering

results due to bad choice of randomly selected K initial exemplars [61], the affinity

propagation algorithm is able to generate good clustering results without predetermining

the initial exemplars. This algorithm allows all the data points to have equal chance

to become exemplars and is easy to be implemented, thus it is chosen in this thesis to

cluster the RPs.

The affinity propagation algorithm generates a set of exemplars and corresponding

clusters by recursively transmitting real-valued messages between data points with an

input measure of similarity between pairs of data points [15]. The pairwise similarity

s(i, j) indicates the suitability of data point j to be the exemplar of data point i. Another input measure is the preference, which is also the self similarity for data point k,

p(k) = s(k, k). This value defines the a priori possibility that data point k to become an

exemplar. If all the data points are equally possible to be exemplars, then their preferences can be set to a common value. High preference values will lead to large number

of clusters generated by the algorithm. In practice, the preference values are commonly

assigned as the minimum or median similarity to generate moderate number of clusters.

The core operations of the algorithm is the transmission of two kinds of real-valued

messages: responsibility message, r(i, j) and availability message, a(i, j). The responsibility message, r(i, j), is sent from data point i to candidate exemplar j to reflect the

suitability of data point j to serve as the exemplar for data point i taking into considerations the other potential exemplars. It is updated according to

r(i, j) = s(i, j) − ′ max {a(i, j ′ ) + s(i, j ′ )}

′

j s.t.j ̸=j

(2.12)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-37-2048.jpg)

![25

Chapter 2. Background and Related Works

The availability message, a(i, j) is sent from candidate exemplar j to data point i

to reflect how appropriate that data point i should choose data point j as its exemplar,

taking into account the responsibility messages from other data points that data point j

should be an exemplar. Its update rule is:

a(i, j) = min 0, r(j, j) +

∑

max{0, r(i′ , j)}

i′ s.t.i′ ̸={i,j}

(2.13)

Two additional messages: self-responsibility, r(i, i) and self-availability, a(i, i) are also

calculated for each data point i. These messages reflect accumulated evidence that i is

an exemplar. The formulas to update these two messages are stated below:

r(i, i) = p(i) − ′ max {a(i, j ′ ) + s(i, j ′ )}

′

a(j, j) =

∑

j s.t.j ̸=j

max{0, r(i′ , j)}

(2.14)

(2.15)

i′ s.t.i′ ̸=j

The exemplars can then be identified by combining the two messages. For data point

i, find

j ′ = arg max{a(i, j) + r(i, j)}

(2.16)

j

If j ′ = i, then data point i is an exemplar; otherwise, data point j ′ is the exemplar

for data point i. The messages are passed recursively between pairs of data points by

following the above updating rules (2.12) to (2.15) until a good set of exemplars and

corresponding clusters gradually emerges.

2.6

Compressive Sensing Theory

This thesis describes how the localization problem can be re-formulated into a sparse

signal recovery problem, so that the compressive sensing theory discussed in [16, 62, 63]

can be applied to estimate the user’s location.

Compressive sensing theory allows compressible signals to be recovered by fewer samples than traditional methods, which according to the Nyquist sampling theory requires](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-38-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 2. Background and Related Works

26

the sampling rate to be at least twice the maximum bandwidth. This is possible when

signals of interest are sparse and are sampled incoherently. The compressive sensing

problem can be formulated as follow [16, 63]:

Consider a discrete-time signal x as a N × 1 vector in RN . Such signal can be

represented as a linear combination of a set of basis {ψ i }N . Constructing a N × N basis

i=1

matrix Ψ = [ψ 1 , ψ 2 , ...ψ N ], the signal x can be expressed as

x=

N

∑

si ψi = Ψs

(2.17)

i=1

where s is a N × 1 vector and is an equivalent representation of x in the different basis

Ψ. A signal is K-sparse when it can be represented as a linear combination of K ≪ N

basis vectors. This means that there is only K nonzero entries for vector s.

The overall compressive sensing problem can be expressed as

y = Φx = ΦΨs = Θs

(2.18)

where Φ is a M × N , M < N measurement sensing matrix for sensing the signal x,

Θ = ΦΨ is an M × N matrix, and y is a M × 1 observation vector collected as a

result of this sensing process. This problem can be referred to as incoherent sampling

if the largest correlation between the sensing matrix Φ and the representation basis Ψ,

√

µ(Φ, Ψ) = N · max | < ϕi , ψ j > | is small.

1≤i,j≤N

Compressive sensing theory requires both the sparsity and incoherent sampling, so

that the signal can be recovered exactly with high probability. If M ≥ cKlog(N/K) ≪ N ,

where c is a small constant, the signal can be reconstructed by solving the following l1

norm minimization problem:

s = arg min ∥s∥1 such that Θs = y

ˆ

(2.19)

s∈RN

This is a convex optimization problem that can be easily converted into a linear program,

known as basis pursuit, through primal-dual method [62, 64]. Additional algorithms](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-39-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 2. Background and Related Works

27

to solve this optimization problem can also be found in [64]. In this thesis, the ℓ1 minimization problem is solved by using the basis pursuit linear program provided in the

matlab toolbox, ℓ1 -MAGIC, developed by Cand`s [65].

e

2.7

Chapter Summary

This chapter gives a brief overview of different methods developed for the RSS-based

WLAN indoor positioning systems. It also discusses how the reduction of the region of

interest and selection of access points can enhance the accuracy of these systems. Two

fingerprinting methods, KNN and kernel-based probabilistic techniques are described in

details, as they are served as the performance benchmarks for the proposed positioning system. Moreover, several indoor tracking techniques that are able to improve the

accuracy through the use of previous estimates and pedestrian motion models are also

discussed. The developments of indoor navigation systems are also included to provide

some insight on how the location information produced by the positioning and tracking

systems can be used.

Finally, the affinity propagation algorithm for clustering data points and the compressive sensing theory for sparse and incoherent sampled signals are discussed, these

concepts are used by the proposed positioning and tracking systems.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-40-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 3. Compressive Sensing Based Positioning System

31

interest and N is the total number of RPs. The columns of Ψ(o) represent the average

RSS readings at each RP, which can be referred to as the radio map vector and is denoted

as

(o)

(o)

ψ j = [ψ1,j

(o)

ψ2,j

···

(o)

ψL,j ]T ,

j = 1, 2, . . . , N

(3.2)

Besides the average RSS reading matrix Ψ(o) , the database server also stores the

variance of these time samples, which are useful in determining which APs should be

selected for localization. The variance vector for each RP is defined as

(o)

(o)

∆j = [∆1,j

(o)

where ∆i,j =

1

q−1

∑q

(o)

τ =1 (ψi,j (τ )

(o)

∆2,j

···

(o)

∆L,j ]T ,

j = 1, 2, . . . , N

(3.3)

(o)

− ψi,j )2 is the unbiased variance of RSS readings from

AP i at RP j for orientation o.

For each RP j, its position represented as Cartesian coordinates (xj , yj ), together with

its average and variance of the RSS readings from different APs at different orientations

(o)

(o)

form a set of (xj , yj ; ψ j ; ∆j ), o ∈ O, which is stored in the fingerprint database. The

database is then preprocessed as described in the next subsection before being used for

the computation of position estimation during online phase. Note that if there is no RSS

readings collected from an AP at a RP and an orientation, the corresponding value in

the fingerprint database is set to a small value to imply its invalidity.

3.2.2

Clusters Generation by Affinity Propagation

Due to the time varying characteristics of the indoor propagation channel, RSS readings

collected during online phase may deviate from those stored in the radio map database.

As a result, these deviation may lead to error estimation of position. In addition, the

computation time for finding position updates increases proportionally to the number of

RPs. Therefore, a coarse localization stage is introduced at the online phase to confine

the localization problem into a smaller region, namely a subset of RPs that have similar

RSS readings to the online measurement, before the fine localization is performed. This](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-44-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 3. Compressive Sensing Based Positioning System

32

stage can effectively reduce the computation time due to the reduction of number of

relevant RPs, as well as the errors introduced by the potential outliers.

The RPs collected in the offline phase are required to be divided into subsets, so that

a coarse localization stage can take place during the online phase. The RPs whose RSS

readings are similar and physically close to each other should belong to the same group.

This group division process, which is referred to as the clustering process in the proposed

system is done during the offline phase after the fingerprints collection is finished. Since

the RSS readings for the same RP vary for the four orientations, the clustering process

is performed on each of the four radio map databases separately.

The affinity propagation algorithm described in Section 2.5 is used to generate the

desirable clusters, as this algorithm allows all the RPs to have equal chances to be

exemplars and is easily to be implemented. It requires two input parameters, namely the

similarity between pairs of RPs and the preference values. At orientation o, the similarity

between RP i and RP j is defined as

(o)

(o)

s(i, j)(o) = −∥ψ i − ψ j ∥2 , ∀i, j ̸= i ∈ {1, 2, ..., N }, o ∈ O

(3.4)

Since all of the RPs are equally desirable to be exemplars, their preferences are set

to a common value. In order to generate a moderate number of clusters, the common

preference for orientation o is defined as

p(o) = γ (o) · median{s(i, j)(o) , ∀i, j ̸= i ∈ {1, 2, ..., N }}, o ∈ O

(3.5)

where γ (o) is a real number which is experimentally determined, such that a desired

number of clusters is generated.

For each orientation, o ∈ O, the affinity propagation algorithm takes the above definitions of similarity (3.4) and preference (3.5) as inputs and then it recursively updates

the responsibility messages and availability messages according to (2.12) to (2.15) until

a good set of exemplars and the corresponding clusters emerges [15]. This set of generated exemplars is denoted as H(o) and the corresponding cluster member set with RP](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-45-2048.jpg)

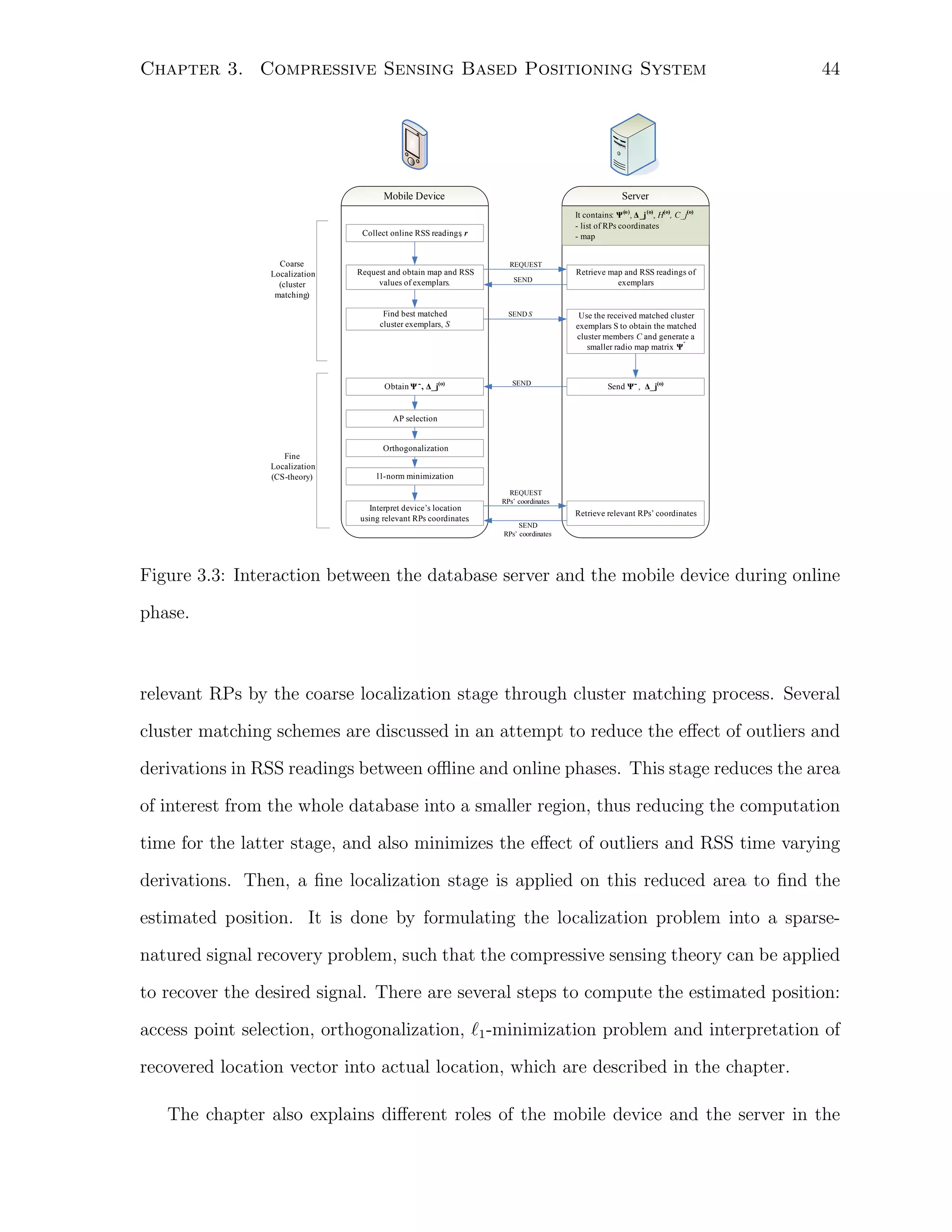

![Chapter 3. Compressive Sensing Based Positioning System

Mobile Device

34

Server

Collect RSS time samples from APs

at RP j for 4 orientations

Compute the average and variance of

RSS readings over time, _j (o), _ j(o)

∆

ψ

Send RP j’ s information:

_j (o), _j (o) & coordinates (x_j, y_j)

SEND

Collect fingerprint for RP j

in 4 orientations

∆

Use the device to

collect N RPs

ψ

Create overall radio map matrix:

(o)

= [ _ 1(o), _ 2(o),…, _N (o)]

ψ

ψ

ψ

Ψ

Apply affinity propagation on each

radio map to generate sets of

exemplars H(o) and their

corresponding members C_j (o)

Outlier adjustment

for each radio map

Figure 3.2: Interaction between the database server and the mobile device during offline

phase.

measurement vector at time t is denoted as

r(t) = [r1 (t), r2 (t), · · · , rL (t)]T

(3.6)

where {rk (t), k = 1, ..., L} is the online RSS readings from AP k at time t. Since the

positioning system does not take into account the previous estimate, the time dependency

notation (t) is dropped in this chapter for simplicity purpose, i.e. the online RSS reading

is denoted as r instead of r(t).

As shown in Fig. 3.1, the collected measurement vector is the input to the proposed

positioning system. First, it is used in the coarse localization stage to reduce the area of

interest. Then it is also used in the fine localization stage to obtain the final estimated

position. The details of these two stages are described in the following sections.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-47-2048.jpg)

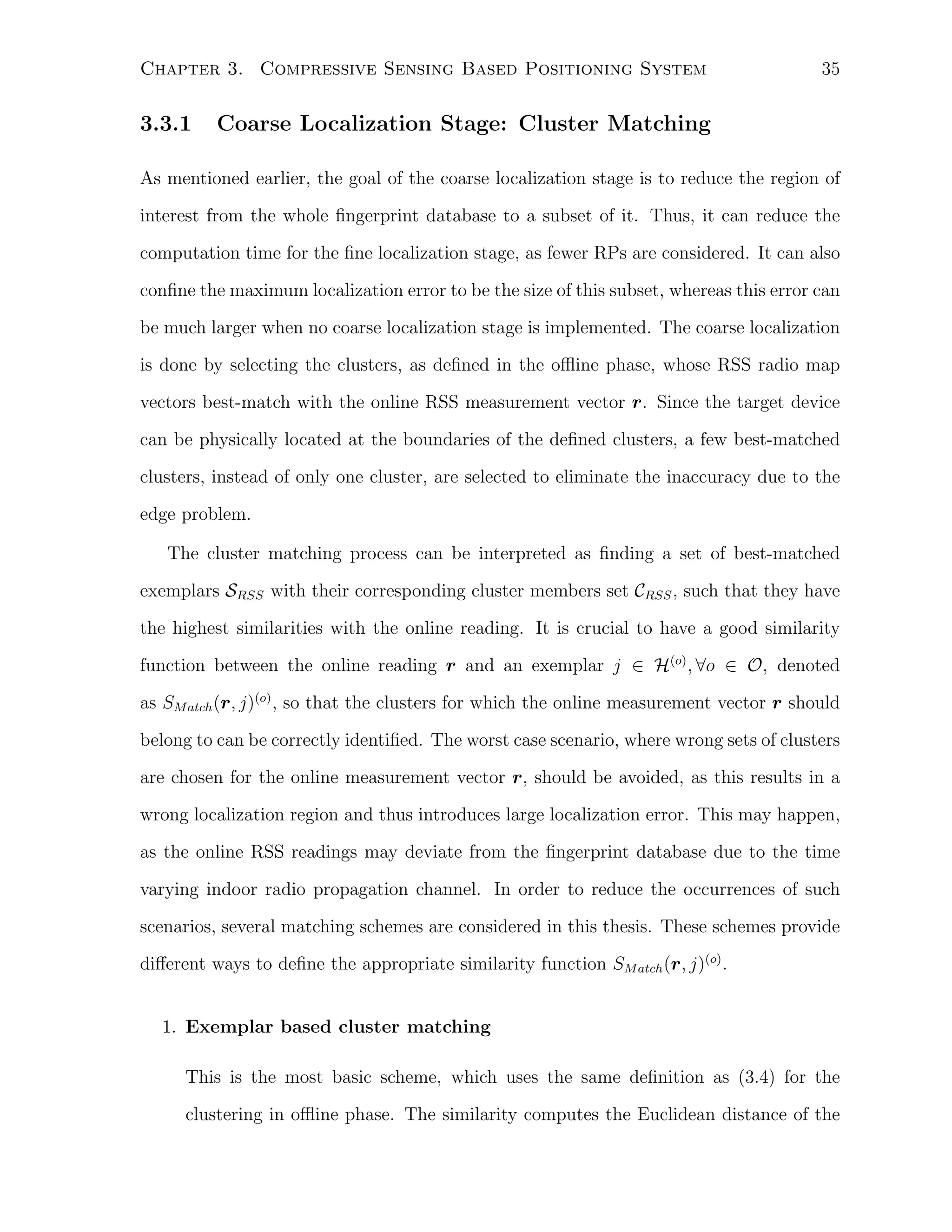

![38

Chapter 3. Compressive Sensing Based Positioning System

be a high percentage, α1 , of the maximum similarity difference, that is

α = α1 ·

max

j∈H(o) ,o∈O

{

}

SM atch (r, j)(o) + (1 − α1 ) ·

min

j∈H(o) ,o∈O

{

SM atch (r, j)(o)

}

(3.15)

Finally, the region of interest of the localization problem can be reduced to the set of

˜ ˜ ˜

CRSS . The modified radio map matrix ΨL×N , N = |CRSS | can be obtained as

(o)

˜

Ψ = [ψ j , ∀(k, o) ∈ CRSS ].

(3.16)

This matrix will then be used by the following fine localization stage. Note it is

possible that this matrix may contain the radio map vectors from the same RP but at

different orientations, as all clusters from different orientations are considered for cluster

matching.

3.3.2

Fine Localization Stage: Compressive Sensing Recovery

The fingerprint-based localization problem can be reformulated as a sparse signal recovery

problem, as the position of the mobile user is unique in the discrete spatial domain. By

assuming that the mobile user is located exactly at RP j and facing at orientation o, such

that (j, o) ∈ CRSS , the user’s location can be represented relative to these RPs instead

of the actual location. The mathematical representation is a 1-sparse vector, denoted as

θ N ×1 , whose elements are all equal to zero except the n-th element, so that θ(n) = 1,

˜

where n is the corresponding index of the RP at which the mobile user is located, that is

θ = [0, ..., 0,

1

, 0, ..., 0]T

(3.17)

nth element

Then, the online RSS measurement r obtained by the mobile device can be expressed

as:

˜

y = Φr = ΦΨθ + ε

(3.18)

˜

where Ψ is the modified radio map matrix as defined in (3.16) and ϵ is an unknown

measurement noise. The matrix ΦM ×L is an AP selection operator applied on the online](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-51-2048.jpg)

![39

Chapter 3. Compressive Sensing Based Positioning System

RSS measurement vector r to obtain vector y, where M < L is the desired number of

APs to be selected.

Based on this sparse signal recovery formulation, the following parts explain how the

location of the mobile user can be recovered by using the compressive sensing theory.

A. Access Points Selection

Since most modern buildings are equipped with a large number of APs to ensure good

quality of wireless services, the total number of detectable APs in these buildings, L is

often much greater than that required for positioning. These extra APs lead to excessive

computations and possibly biased estimations if some of the APs are not reliable. Inclusion of RSS readings from unstable APs may introduce error to the estimations, as online

RSS values may deviate from the readings in the offline database. Therefore, an access

point selection step is introduced to select a subset of reliable and stable APs from the

available ones to be used for the actual positioning, in order to eliminate the errors due

to large number of APs. Denote the set of all available APs found within all the RPs by

L with |L| = L. Then the AP selection step is to determine a subset of APs, M ⊆ L,

such that |M| = M ≤ L.

The AP selection process is carried out by applying the AP selection operator Φ on

the online measurement vector r as defined in (3.18). Each row of Φ, is a 1 × L vector

th

that selects the desired lm AP, where lm ∈ M, by assigning ϕ(lm ) = 1 and zero to the

rest of the elements, namely:

ϕm = [0, ..., 0,

1

, 0, ..., 0],

lm ∈ M, ∀m = 1, 2, . . . , M

(3.19)

lm −th element

In this thesis, three AP selection schemes are used based on APs stabilities and

differentiability in spatial domain. Their performances are evaluated in a later chapter.

1. Strongest APs [39]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-52-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 3. Compressive Sensing Based Positioning System

40

This scheme selects the set of M APs with the strongest RSS readings from the

online RSS measurement vector. These APs with strong RSS readings are more

reliable than the ones with weak RSS readings, as they provide a high probability

of coverage over time. The set of APs can be obtained by sorting the elements

of the online measurement vector r in descending order and selecting indices of

the first M values that correspond to the APs with highest RSS readings. Since

the online RSS readings are different for each run, the AP selection operator Φ is

created dynamically on the device for each update during the online phase.

2. Fisher Criterion [38, 66]

This scheme selects the APs which discriminate themselves the best within RPs.

The discrimination ability for each AP i, i ∈ {1, 2, . . . , L} can be quantified through

the Fisher criterion. The metric for AP i, denoted as ξi is defined as

∑

ξi =

(o)

(j,o)∈CRSS (ψi,j

∑

(j,o)∈CRSS

¯

where ψi =

1

˜

N

∑

(j,o)∈CRSS

¯

− ψi )2

(o)

(3.20)

∆i,j

(o)

ψi,j . The APs with highest ξi are chosen to construct

the AP selection operator Φ for the actual localization. This metric accounts

for two factors: the denominator ensures that RSS values should not vary too

much over time, thus implies that the offline and online values are similar and

the numerator evaluates the discrimination ability of each AP by considering the

strength of variations of mean RSS across RPs. Since this metric calculations are

done across the RPs j at orientation o chosen in the coarse localization stage,

(j, o) ∈ CRSS , the AP selection operator Φ is created dynamically on the device for

each update during the online phase.

3. Random Combination

Unlike the above two schemes, which select the appropriate APs based on different

criteria and create the AP selection operator Φ dynamically for each update, the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-53-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 3. Compressive Sensing Based Positioning System

41

random combination scheme does not take into account the performance of the

APs and thus have less computation complexity during online phase and also does

not require large number of RSS time samples for the variance calculation in the

offline phase as required by the Fisher criterion. The AP selection operator Φ is

defined as a randomly generated i.i.d. Gaussian M × L matrix. Thus, according to

(3.18), y = Φr, y is a set of M linear combinations of online RSS values from L

APs. Since the same matrix can be reused for each update, it can be generated and

stored first during the training period and retrieved for use directly in the online

phase, saving the time to dynamically generate the matrix as required by the other

two schemes.

B. Orthogonalization and Signal Recovery using ℓ1 -minimization

Compressive sensing theory requires both sparsity and incoherence of the signal, so that

it can be recovered accurately. Although the localization problem as defined in (3.18)

˜

satisfies the sparsity requirement, Φ and Ψ are in general coherent in the spatial domain.

Thus, an orthogonalization procedure is applied to induce the incoherence property as

required by the CS theory [67, 68].

The orthogonalization process is done by applying an orthogonalization operator, T,

on the vector y, such that z = Ty. The operator is defined as

T = QR†

(3.21)

˜

where R = ΦΨ, and Q = orth(RT )T , where R† is a pseudo-inverse of matrix R and

orth(R) is an orthogonal basis for the range of R. By applying this operator on y, (3.18)

becomes:

z = Ty = QR† y

= QR† Rθ + QR† ε

= Qθ + ε′

(3.22)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-54-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 3. Compressive Sensing Based Positioning System

42

˜

where ε′ = Tε. If M is in the order of log N , the minimum bound required by the

CS theory, θ can be well-recovered from z with very high probability, by solving the

following ℓ1 -minimization problem [67, 68].

ˆ

θ = arg min ∥θ∥1 ,

s.t. z = Qθ + ε′ .

(3.23)

˜

θ∈RN

The computation complexity of the ℓ1 -minimization algorithm grows proportional to

the dimension of vector θ, which is the number of potential RPs. Therefore, the coarse

localization stage, which reduces the area of interest from all the N RPs into a subset

˜

of N < N RPs, reduces the computational time and resources required for solving the

ℓ1 -minimization problem, and thus allows this procedure to be carried out by resourcelimited mobile devices.

C. Interpretation of Actual Position

The above procedure is able to recover the exact position, if the mobile user is located at

one of the RPs facing one of the orientations in the set of O, which is the assumption made

earlier in order to formulate the localization problem into a 1-sparse natured problem.

However, in real situation, the mobile user may not be located at an RP facing a certain

ˆ

orientation. Thus, in actual implementation, the recovered position vector θ is not a

1-sparse vector, rather a vector with a few non-zero coefficients. A post-processing step

ˆ

is conducted to interpret this recovered location vector θ into an actual location and

compensate the error induced by the grid assumption. The procedure chooses the set of

ˆ

all indices of the dominant elements in θ, which are above a certain threshold λ, denoted

as R

ˆ

R = {n|θ(n) > λ}

(3.24)

ˆ

λ = λ1 max(θ)

(3.25)

where λ1 is a parameter within a range (0, 1) and is adjusted experimentally. Then, the

estimated location of the mobile user can be calculated as a weighted average of these](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-55-2048.jpg)

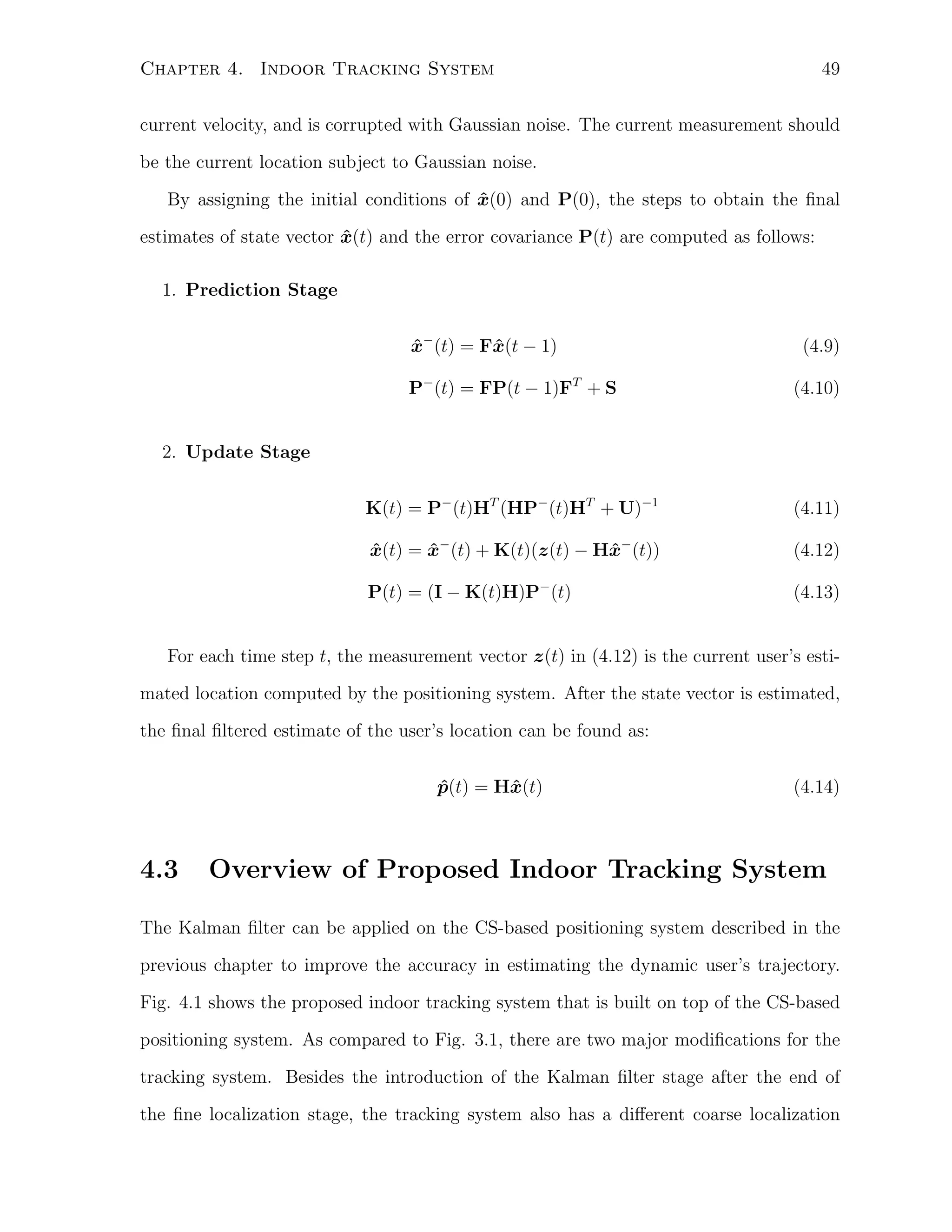

![Chapter 4

Indoor Tracking System

The previous chapter describes a positioning system that can accurately estimate a stationary user’s position. This positioning system is modified in this chapter in order to

track the dynamic mobile user. The proposed indoor tracking system uses the Kalman

filter with map information to smooth out the location estimate and also uses previous

position estimate to choose the relevant region of interest in the coarse localization stage.

This chapter first describes the Kalman filter and then the proposed indoor tracking

system.

In this chapter, the tracking problem is defined as follows. The device carried by

the mobile user periodically collects the online RSS readings from each APs at a time

interval ∆t, which is limited by the device’s network card and hardware performances.

The online RSS readings vector is denoted as r(t) = [r1 (t), r2 (t), . . . , rL (t)], t = 0, 1, 2, ...,

where rl (t) corresponds to the RSS from AP l at time t. Then, the indoor tracking system

uses these RSS readings to estimate the user’s location at time t, which is denoted as

p(t) = [ˆ(t), y (t)]T .

ˆ

x

ˆ

46](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-59-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 4. Indoor Tracking System

4.1

47

General Bayesian Tracking Model

The tracking problem of a mobile user can be modeled by a general Bayesian tracking

model as follows [41] and [47]:

x(t) = ft (x(t − 1), w(t))

(4.1)

z(t) = ht (x(t), v(t))

(4.2)

where x(t) = [x(t), y(t), vx (t), vy (t)] is the state of the user at time t with (x(t), y(t))

as the Cartesian coordinates of the user’s location and vx (t) and vy (t) as the velocities

in x and y directions, respectively. Assuming the tracking is a Markov process of order

one, the state evolves as a function ft of previous state and w(t), i.i.d. process noise

vector only. In addition, the measurement z(t) depends on the current state and the

i.i.d. measurement noise vector v(t) through the function ht .

The current location of the mobile user, x(t) can then be estimated recursively from

the set of measurements up to time t, i.e. z(1 : t) = {z(i), i = 1, ..., t}, in terms of the

probability distributive function (pdf), denoted as p(x(t)|z(1 : t)). Assuming that the

initial pdf p(x0 |z 0 ) ≡ p(z 0 ) and p(x(t−1)|z(1 : t−1)) are known, the pdf p(x(t)|z(1 : t))

can be obtained by the following prediction and update stages:

1. Prediction Stage:

The prior pdf p(x(t)|z(1 : t−1)) can be predicted based on p((x(t)|x(t−1)), which

is defined by the state process equation (4.1) and the previous state pdf.

∫

p(x(t)|z(1 : t − 1)) =

p((x(t)|x(t − 1))p(x(t − 1)|z(1 : t − 1))dx(t − 1) (4.3)

2. Update Stage:

Then, the prior pdf can be updated by the measurement z(t) obtained at time t](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-60-2048.jpg)

![48

Chapter 4. Indoor Tracking System

using the Bayes’ rule,

p(z(t)|x(t))p(x(t)|z(1 : t − 1))

p(z(t)|z(1 : t − 1))

∫

p(z(t)|z(1 : t − 1)) = p(x(t)|z(1 : t − 1))dx(t)

p(x(t)|z(1 : t)) =

(4.4)

(4.5)

where p(z(t)|x(t)) is defined by the measurement model (4.2).

4.2

Kalman Filter

If the process and measurement noises are assumed to be Gaussian and the motion

dynamic model is linear, i.e. the process and measurement functions ft and ht are linear

in equations (4.1) and (4.2), then the general Bayesian tracking model is reduced to

a Kalman filter. The optimal solution can be obtained for this Kalman filter as the

minimum mean square estimates (MMSE). The process and measurement equations of

the Kalman tracking model can be formulated as

x(t) = Fx(t − 1) + w(t)

(4.6)

z(t) = Hx(t) + v(t)

(4.7)

where x(t) = [x(t), y(t), vx (t), vy (t)]T is the state vector and z(t) is the measurement

vector. The process noise w(t) ∼ N (0, S) and the measurement noise v(t) ∼ N (0, U)

are assumed to be independent with the corresponding covariance matrices S and U.

The matrices F and H in (4.6) define the linear motion model. For the tracking

problem, they are assigned as follows:

1 0 ∆t 0

0 1 0 ∆t

F=

0

0 0 1

0 0 0

1

1 0 0 0

H=

0 1 0 0

(4.8)

That means the current location of the mobile user is assumed to be the previous location

of the user plus distance traveled, which is computed as the time interval ∆t times the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/au-anthea-ws-201011-masc-thesis-140209003417-phpapp02/75/Au-anthea-ws-201011-ma-sc-thesis-61-2048.jpg)

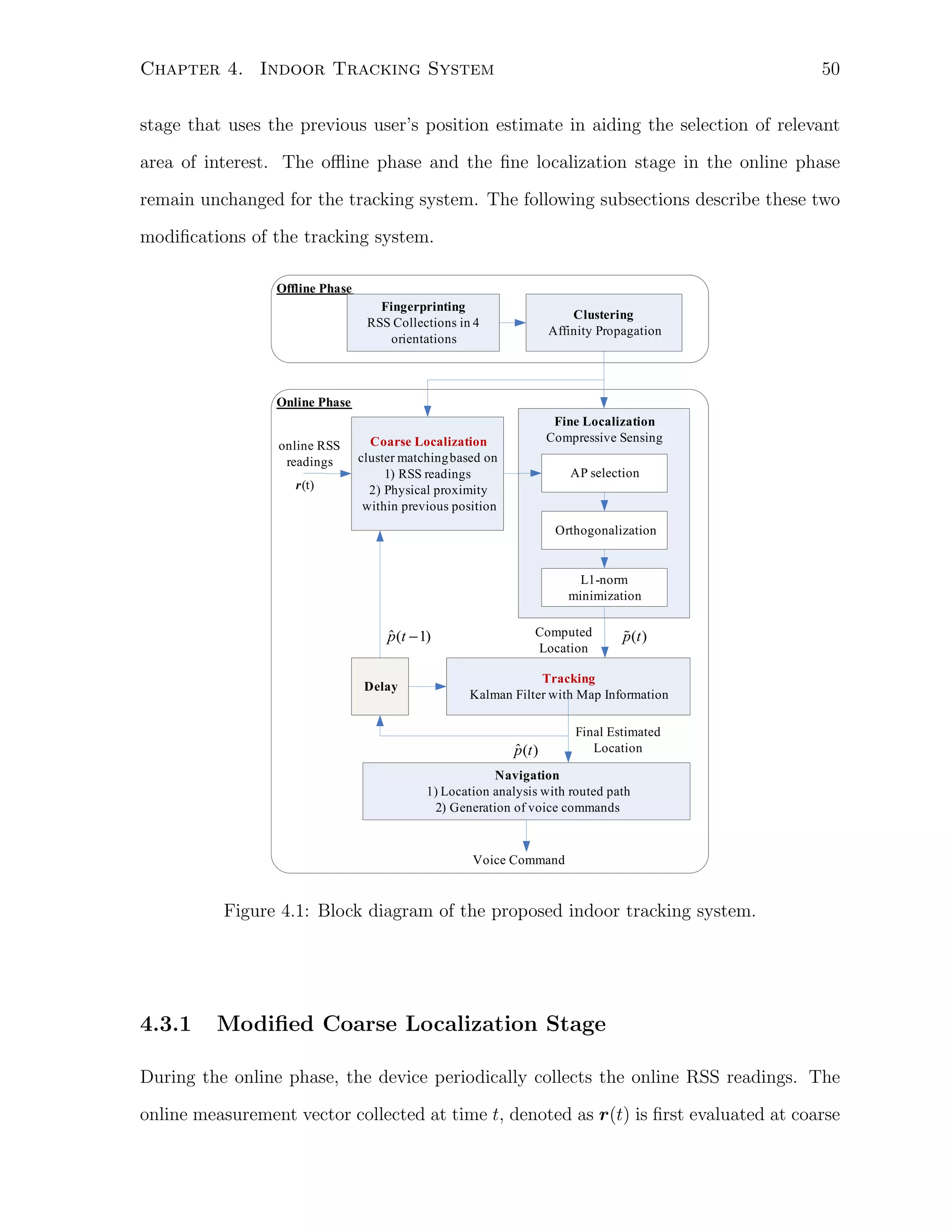

![Chapter 4. Indoor Tracking System

52

Group II: RPs within physical proximity

Besides the use of the online RSS readings to choose the relevant RPs, they can be

chosen by finding the possible range of the device’s current location based on the previous

estimated location, p(t − 1) = (ˆ(t − 1), y (t − 1)). Since a person cannot walk far away

ˆ

x

ˆ

within a short period of time, it is reasonable that the system can limit the region of

interest into the possible walking range based on the previous estimated position, if it is

known and reliable. There are two schemes to choose this possible walking range and are

discussed as follows.