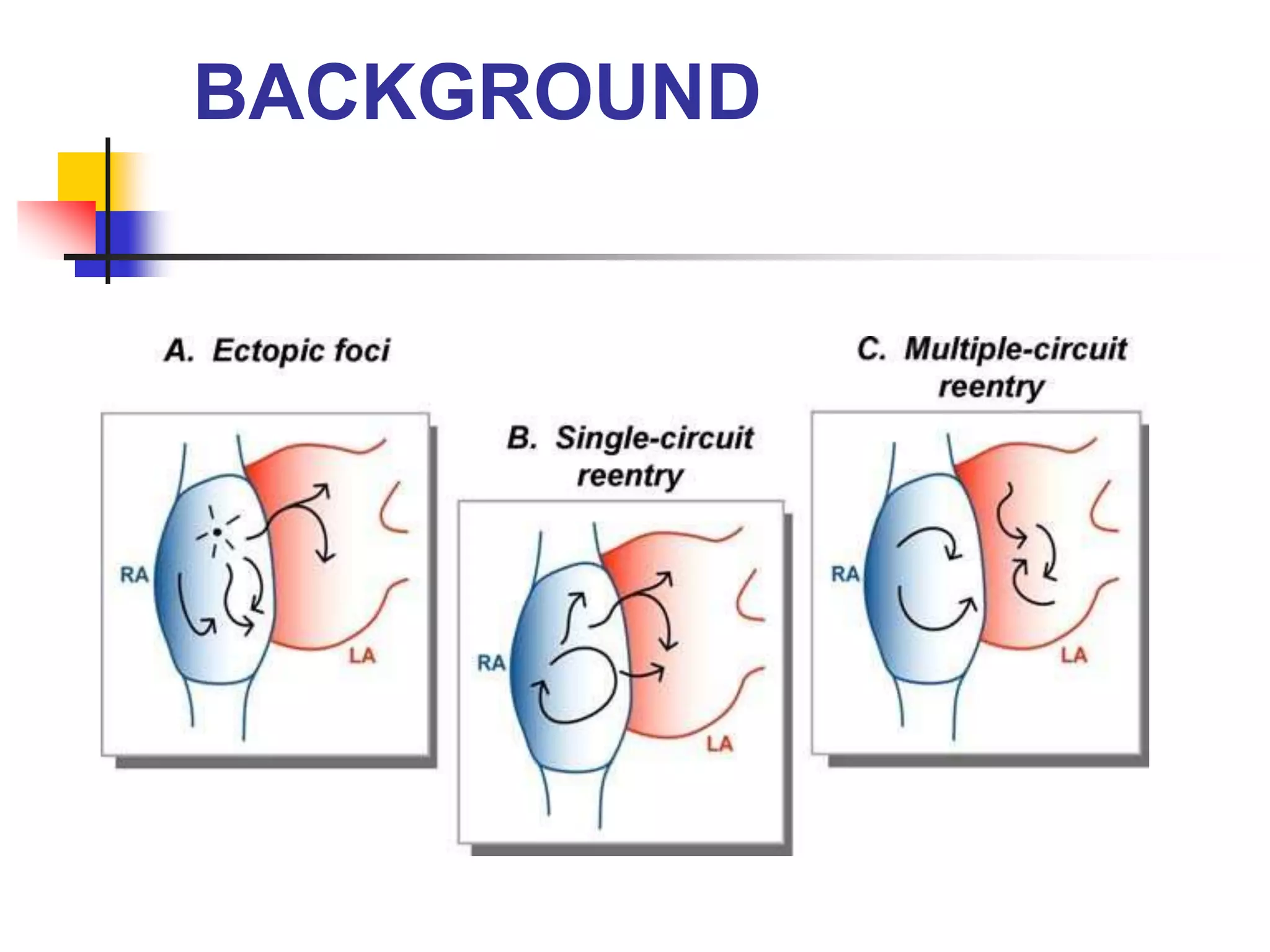

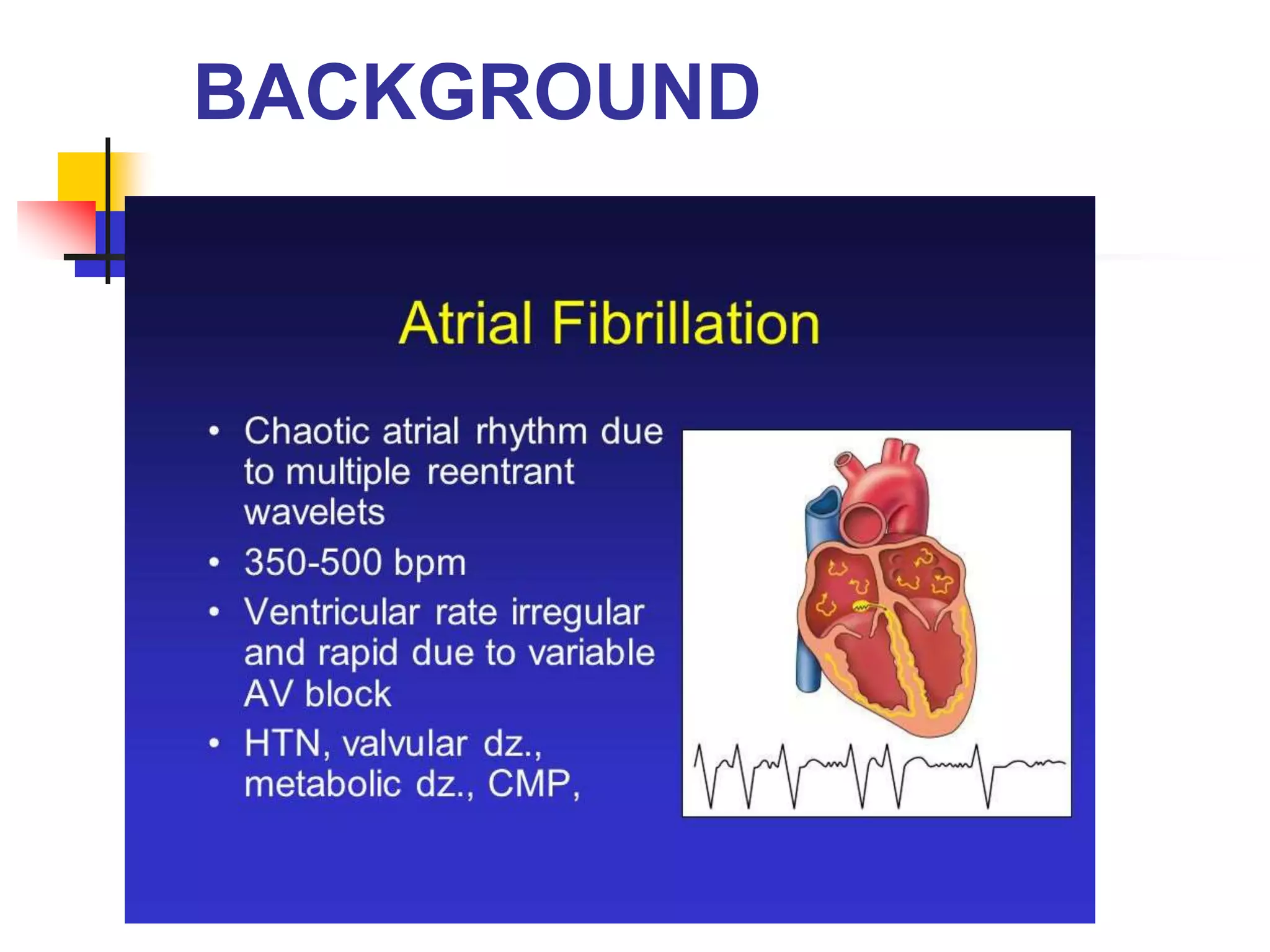

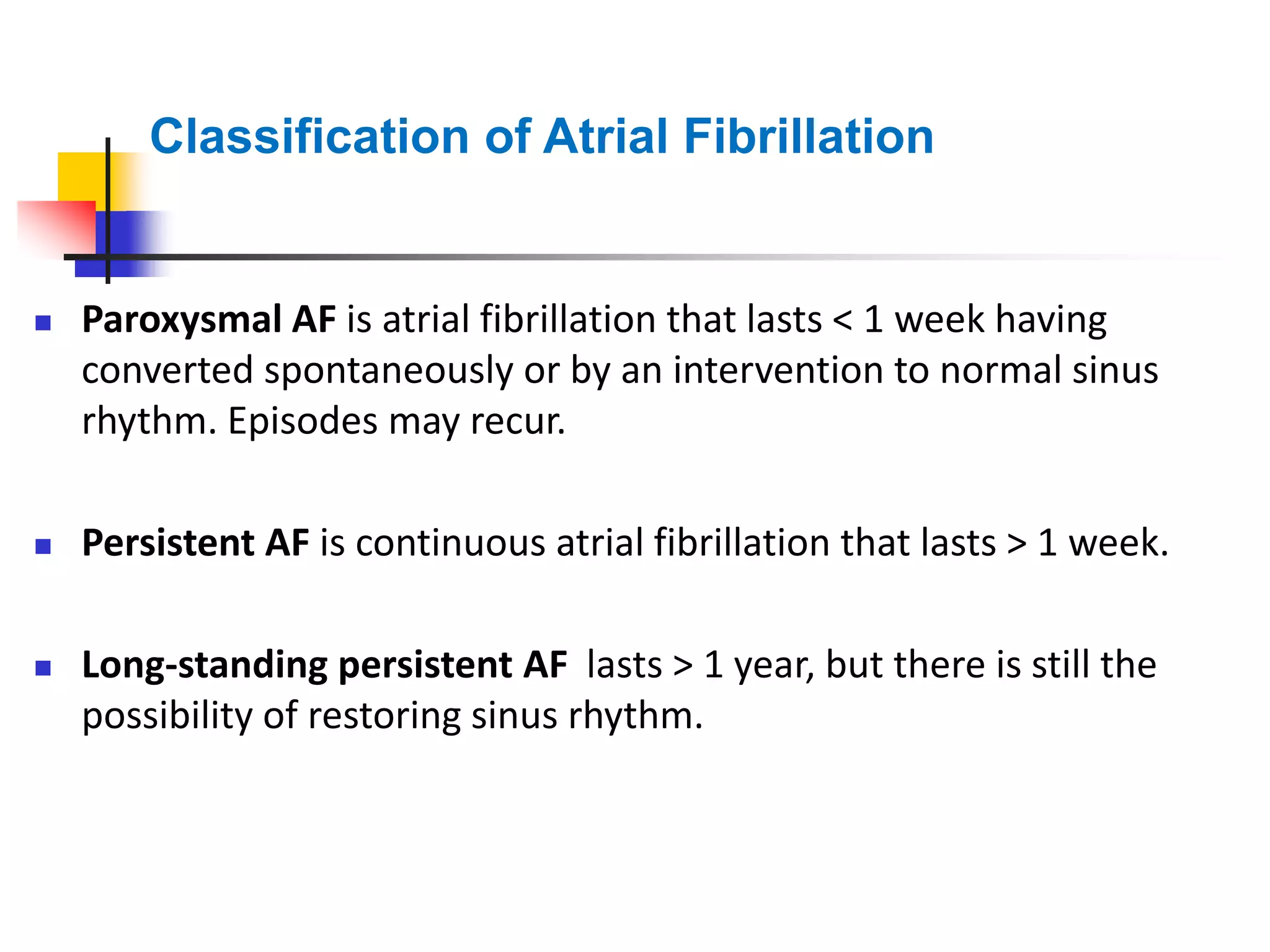

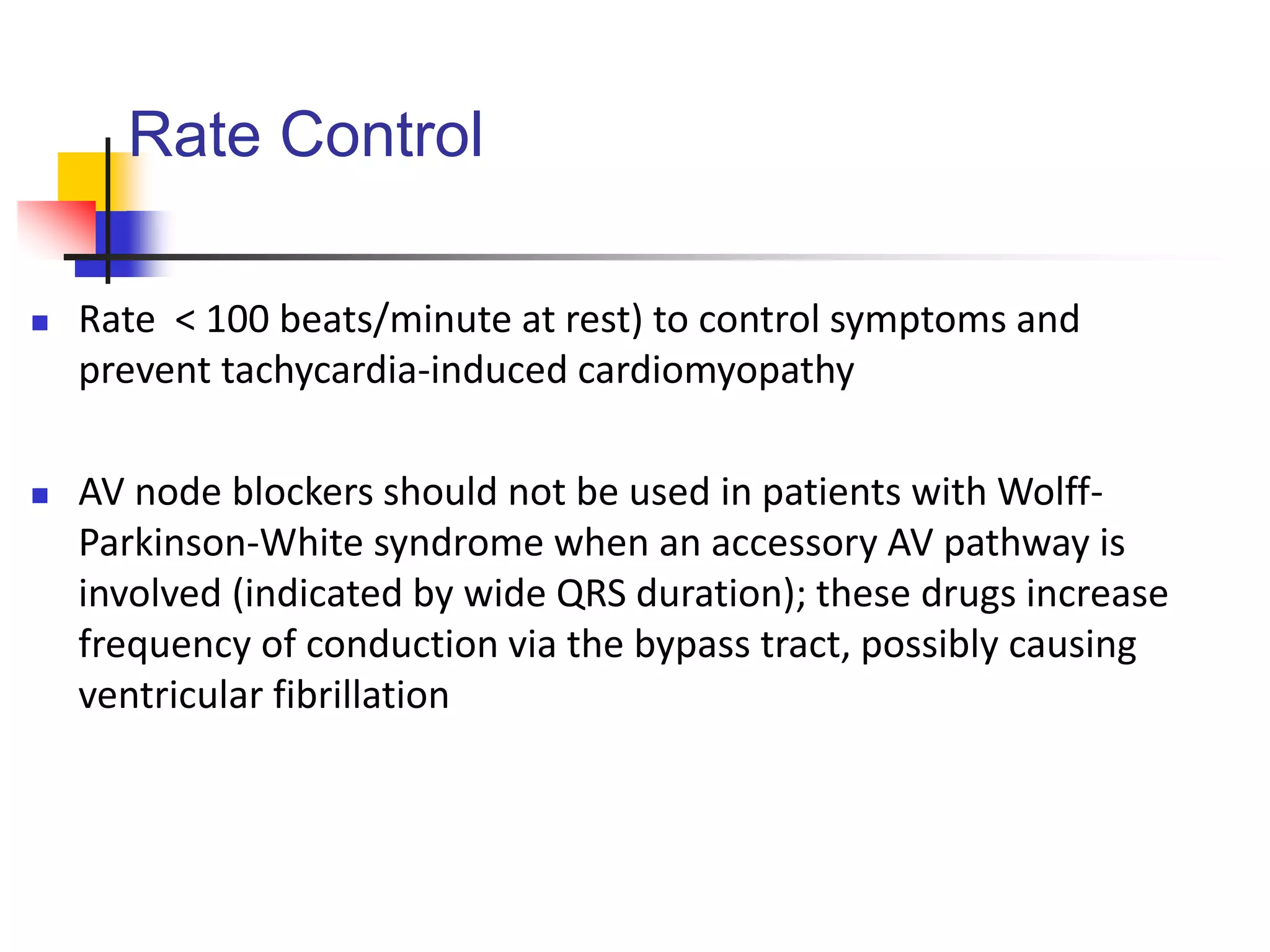

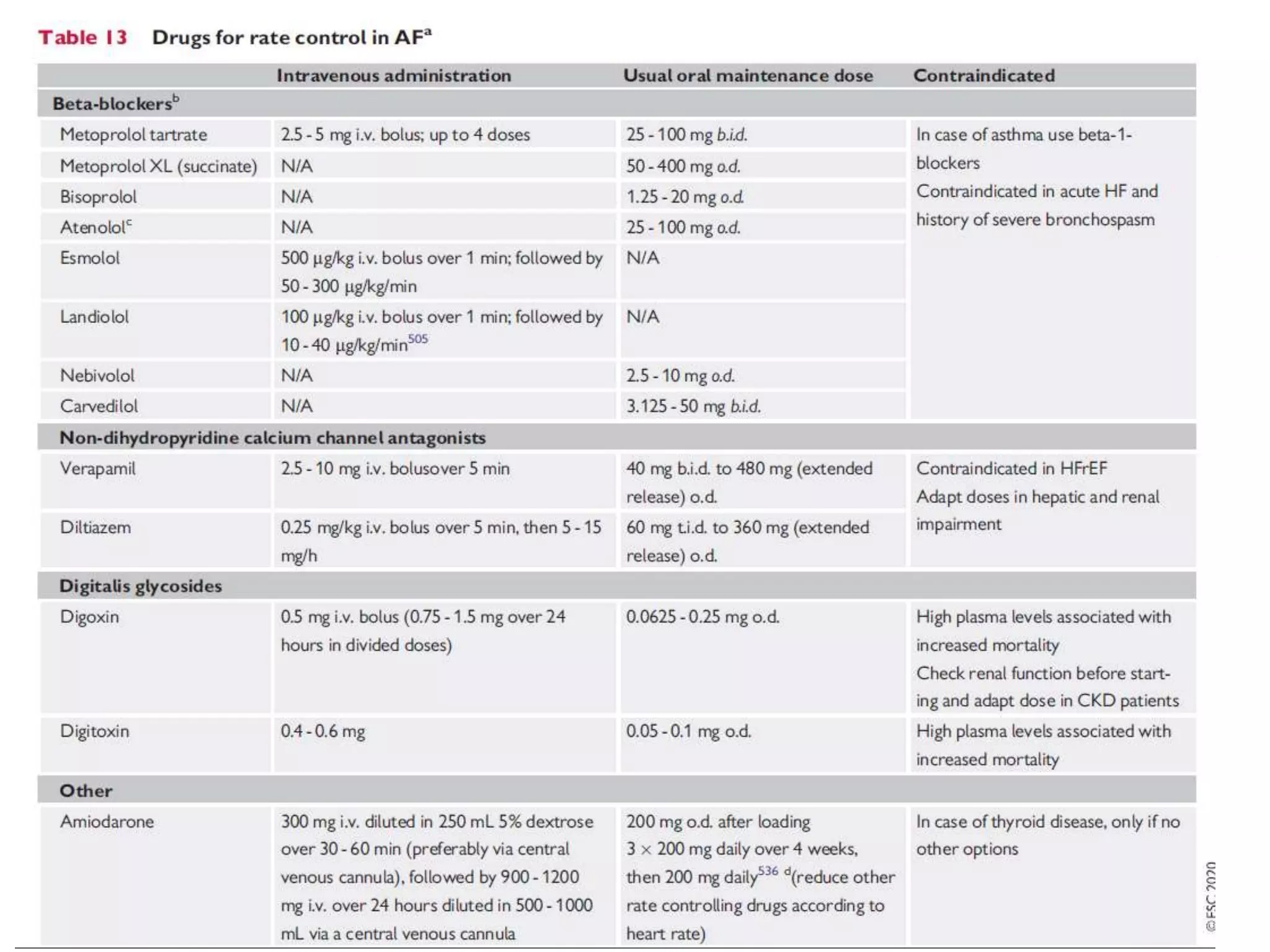

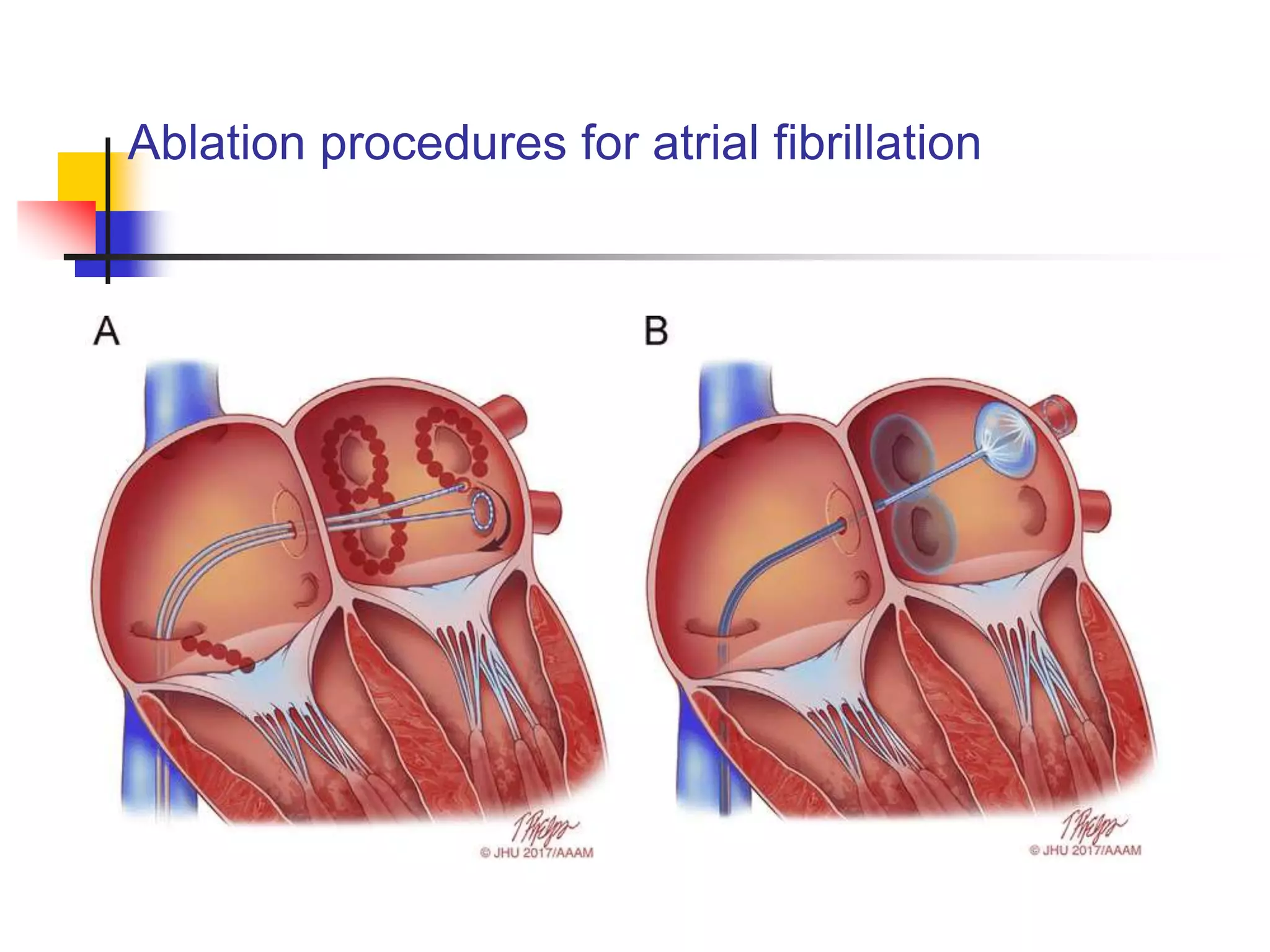

Atrial fibrillation is an irregular heartbeat caused by uncoordinated electrical activity in the atria. It can cause blood clots, heart failure, and stroke. Diagnosis involves an ECG and testing to check for underlying causes like thyroid problems. Treatment focuses on rate control with medications and preventing clots with anticoagulants. Rhythm control methods include cardioversion, medications, and ablation procedures to restore normal sinus rhythm or slow the heart rate. Long term anticoagulation is often needed due to the risk of stroke.