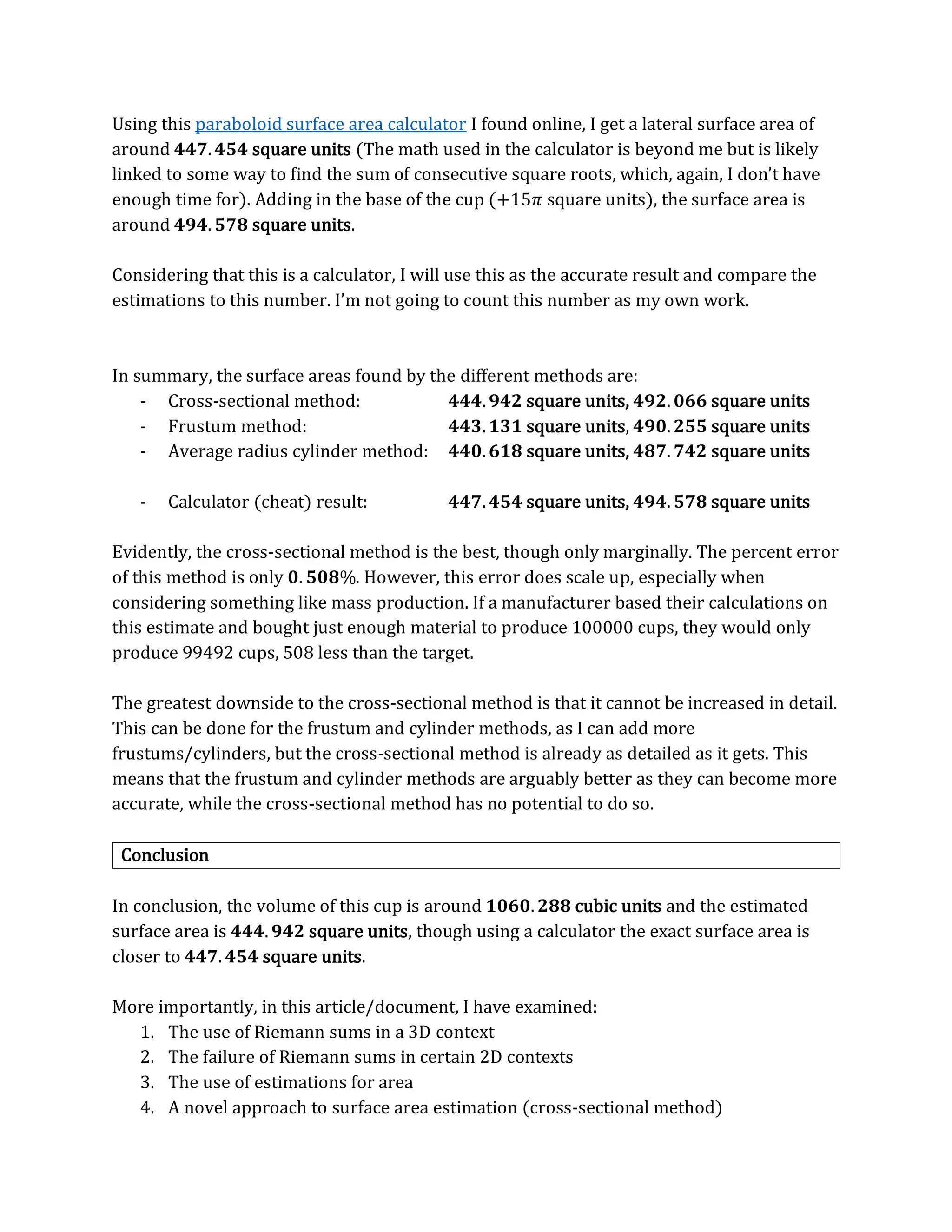

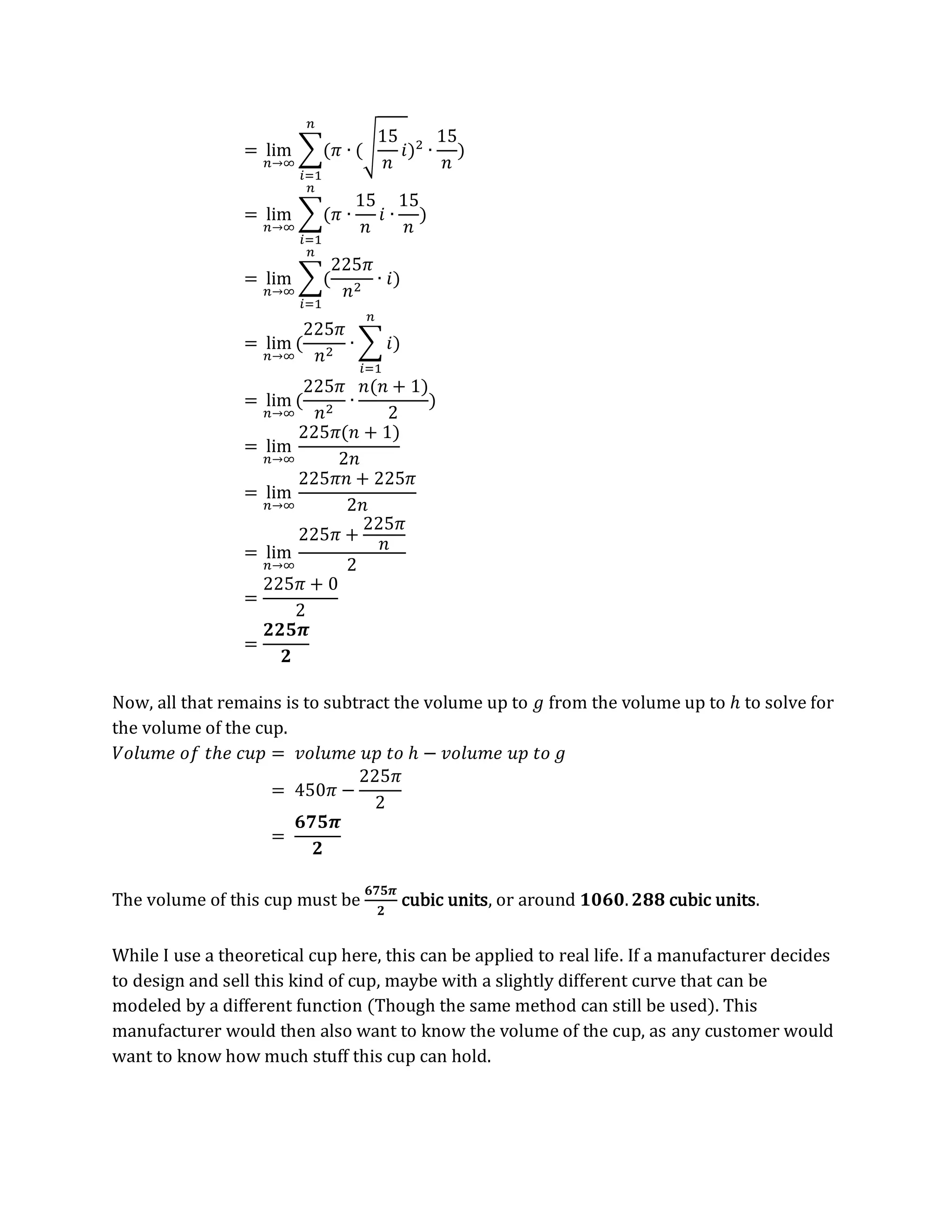

This document discusses finding the volume and surface area of a cup shaped like a paraboloid defined by the function z = x^2 + y^2 from 15 ≤ z ≤ 30. It first finds the volume by approximating the cup as an infinite number of cylinders and calculating the volume of each cylinder. The volume is found to be 675π/2 cubic units. It then discusses using a similar approach to find the surface area but runs into difficulties summing an infinite series. It proposes estimating the surface area using different cross-sectional approximations instead of finding an exact value.

![area), even though the wings are curved in a shape called an airfoil. Much like how the

hypotenuse of a right triangle is not equal to its legs, the actual surface area of a wing is not

equal to the planform area. The planform area only serves as an estimate, yet it is widely

used.

I will examine three estimation methods below and compare to see which is the most

accurate.

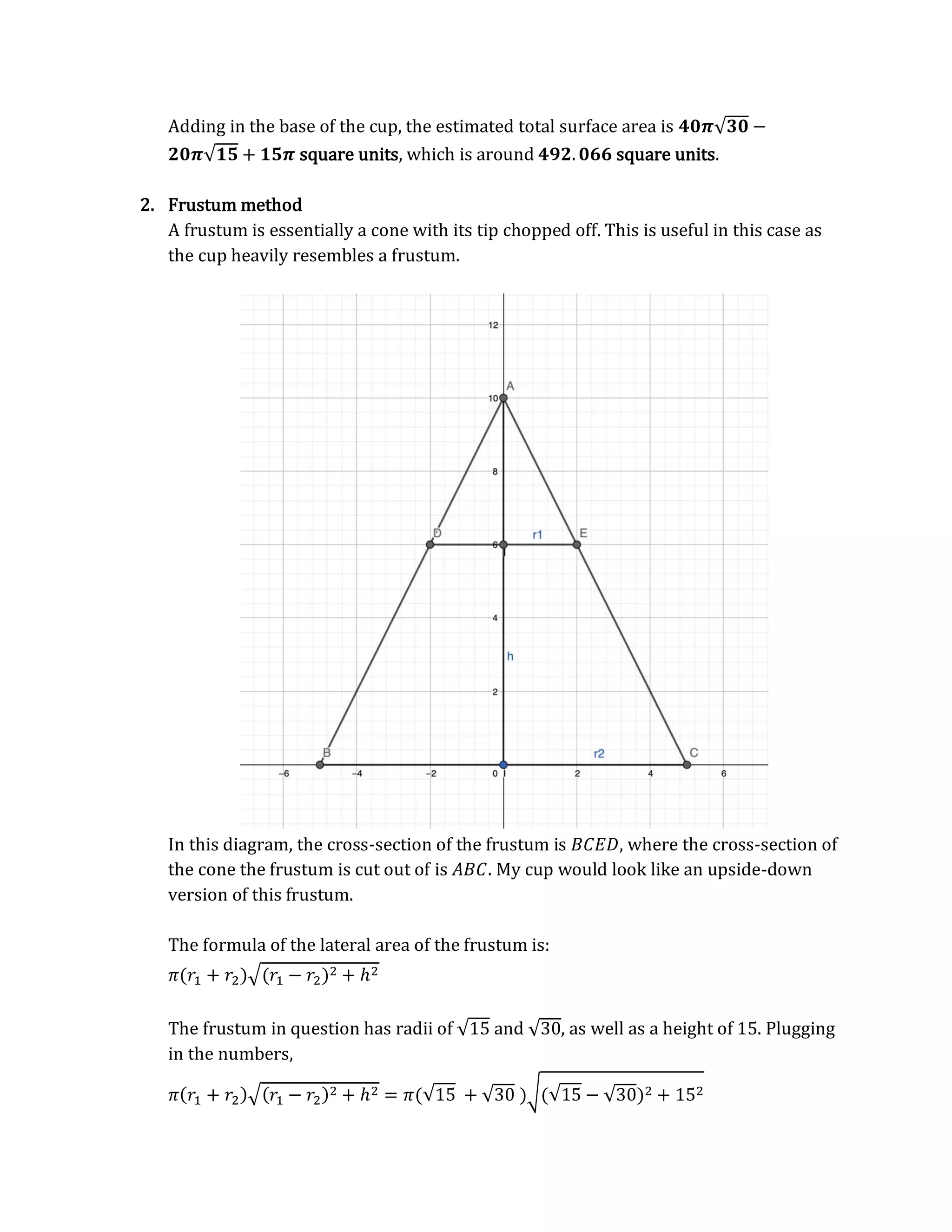

1. Cross-sectional method

This new* method understands the idea of a cylinder in a different way. Instead of

understanding 2𝜋𝑟ℎ as 2𝜋𝑟 ∙ ℎ or 𝑐𝑖𝑟𝑐𝑢𝑚𝑓𝑒𝑟𝑒𝑛𝑐𝑒 ∙ ℎ𝑒𝑖𝑔ℎ𝑡, I can instead understand

it as 2𝑟ℎ ∙ 𝜋 or 𝑐𝑟𝑜𝑠𝑠 𝑠𝑒𝑐𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛𝑎𝑙 𝑎𝑟𝑒𝑎 ∙ 𝜋 . This makes intuitive sense as 𝜋 is the ratio

between the diameter and circumference, and the cross-section acts as a sort of 2D

diameter to the surface area of the cylinder.

* I thought up this idea myself, but I am unsure if somebody else has come up with this before I did. A

brief Google search doesn’t show anything similar, but it may go under a different name.

However, this is only perfectly accurate if the object in question is a cylinder with a

rectangular cross-section. Here, where the cross-section is a section of parabola, I

would expect some error.

Again, the cross-section of a paraboloid is a parabola. In this specific question where

the paraboloid is described by 𝑓(𝑥, 𝑦) = 𝑥2

+ 𝑦2

, the cross-section can be described

by 𝑓(𝑥) = 𝑥2

.

To find the cross-section, I can find the area under 𝑠(𝑥) = −𝑥2

+ 15 then subtract it

from the area under 𝑡(𝑥) = −𝑥2

+ 30, within the domains [−√15,√15] and

[−√30,√30], respectively.

The formula for area under a curve is as follows:

lim

𝑛→∞

∑ 𝑓(𝑎 +

(𝑏 − 𝑎)𝑖

𝑛

)(

𝑏 − 𝑎

𝑛

)

𝑛

𝑖=1

a. 𝒔(𝒙) = −𝒙𝟐

+ 𝟏𝟓

lim

𝑛→∞

∑ 𝑓 (𝑎 +

(𝑏 − 𝑎)𝑖

𝑛

) (

𝑏 − 𝑎

𝑛

)

𝑛

𝑖=1

= lim

𝑛→∞

∑ 𝑠 (−√15 +

(√15 − (−√15))𝑖

𝑛

)(

√15 − (−√15)

𝑛

)

𝑛

𝑖=1

= lim

𝑛→∞

∑ 𝑠 (−√15 +

2𝑖√15

𝑛

)(

2√15

𝑛

)

𝑛

𝑖=1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproject-mahudson-articleon3dcalculus-220531032025-ff05907c/75/Article-on-3D-Calculus-8-2048.jpg)