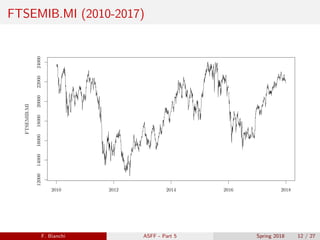

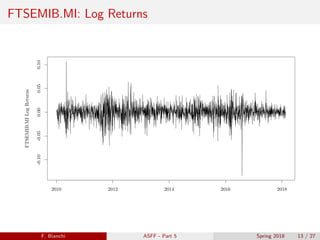

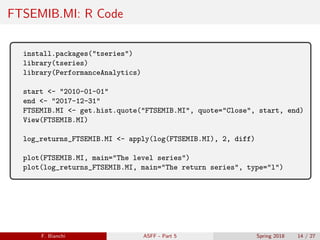

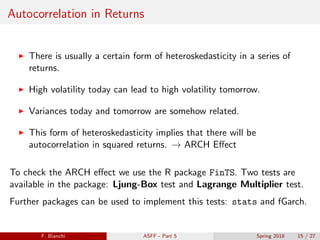

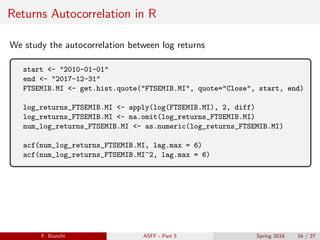

The document discusses advanced topics in applied statistics for finance, specifically focusing on volatility and its modeling through ARCH and GARCH processes. It highlights how these models allow for non-constant volatility and the dependence of asset returns, providing formulas and methodologies for estimating parameters like variance. This includes practical applications and coding examples using R, showcasing how to analyze and visualize financial data and the importance of detecting autocorrelation in returns.

![The COGARCH Model

A further implementation of the GARCH Model is the Continuos GARCH

Model (COGARCH) firstly introduced by Kl¨uppelberg in 2004.

Let Lt be a pure jump L´evy process with finite variation. We define Gt as

a COGARCH(p, q) process with q ≥ p if it satisfies the following system

of stochastic differential equations:

dGt =

√

VtdLt withG0 = 0

Vt = a0 + a Yt−

dYt = BYt−dt + a0 + a Yt− d [L, L]

(d)

t

Where (Vt)t≥0 is a CARMA(q, p − 1) process driven by the discrete part

of the quadratic variation of the L´evy process (Lt)t≥0.

F. Bianchi ASFF - Part 5 Spring 2018 24 / 27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-5handoutasff-180410113244/85/Arch-Garch-Processes-24-320.jpg)

![References

[1] Engle R. (1982) ”Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity with

Estimates of the Variance of UK Inflation”. Econometrica, 50: 987:1008.

[2] Bollerslev T. (1986). ”Generalized Autoregressive Condtional

Heteroskedasticity”. Journal of Econometrics, 31: 307:327.

[3] Duan, J. (1997). ”Augmented GARCH (p,q) process and its diffusion limit”.

Journal of Econometrics, 79, issue 1, p. 97-127.

[4] Kl¨uppelberg C., Maller R. and Lindner A. (2004). ”A continuous time garch

process driven by a L´evy process: stationarity and second-order behaviour.

Journal of Applied Probability.”

[5] Bianchi F., Mercuri L. and Rroji E. (2016). ”Measuring Risk with

Continuous Time Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroscedasticity

models”. SSRN.

[6] Bianchi F., Mercuri L. and Rroji, E. (2017). COGARCH.rm: Portfolio

selection with Multivariate COGARCH(p,q) models. R package version 0.1.0.

F. Bianchi ASFF - Part 5 Spring 2018 27 / 27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-5handoutasff-180410113244/85/Arch-Garch-Processes-27-320.jpg)