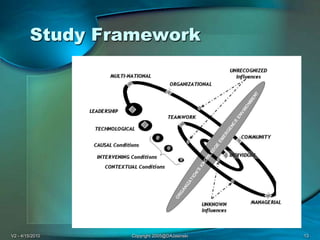

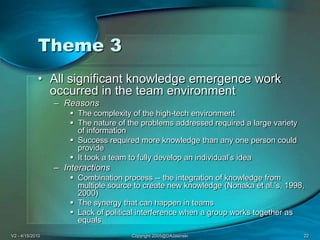

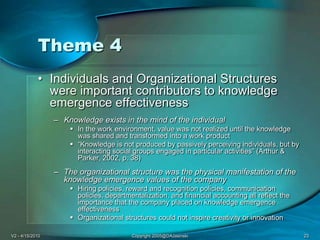

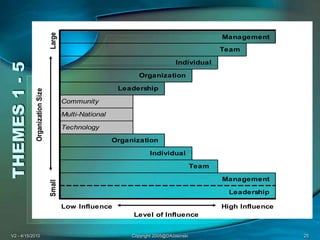

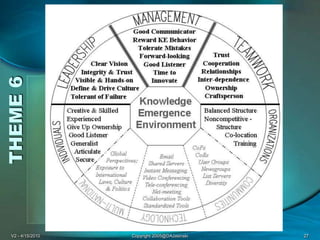

The document presents a grounded theory investigation aimed at developing a knowledge emergence model specifically for high-tech organizations, addressing the complex processes surrounding knowledge creation, sharing, and management. It highlights the significance of effective knowledge emergence environments influenced primarily by management and organizational culture, as well as the importance of teams in solving complex problems. The study's findings provide a framework for leaders to enhance knowledge emergence in their organizations, emphasizing the need for alignment between corporate values and organizational structure.