The article reviews evidence that formally collecting client feedback on the therapeutic alliance and counseling outcomes improves client outcomes. It discusses two ultra-brief measures, the Session Rating Scale and Outcome Rating Scale, that can be used to efficiently obtain this feedback from clients in everyday counseling practice. While client perspectives have been shown to be better predictors of counseling success than counselor perspectives, barriers like time constraints have hindered the routine use of formal client feedback methods. The article argues these two measures provide a feasible way to systematically incorporate clients' views into the counseling process.

![and in a child version, and provides counselors with real-time feedback about

the client’s view of progress or lack thereof (Miller et al., 2004). The ORS has

demonstrated strong internal consistency (α = .87 - .96) and a respectable correlation coefficient (r = .59) with the much lengthier, well-validated OQ-45.2

(Campbell & Hemsley, 2009). The ORS correlation with the OQ-45.2 provides evidence of its construct validity (Reese, Norsworthy, & Rowlands, 2009).

Counselors use of the SRS and ORS is quite high in comparison to their

longer counterparts. For instance, when use of the ORS and OQ-45 were compared over a 12-month period at a community family service agency, the ORS

had an 89% compliance rate and the OQ-45 a 25% compliance rate (Miller

et al., 2003). Similarly, the SRS had a 96% compliance rate and the 12-item

Working Alliance Inventory a 29% compliance rate (Duncan et al., 2003).

These compliance rates, along with their validity and reliability, make the SRS

and ORS well-suited to counseling practice. The practicality of the SRS and

ORS thus makes them a feasible option for counselors wishing to honor the

client’s voice and improve client outcomes via client feedback. Integration of

the SRS and ORS into daily practice also communicates to clients the importance of their voice in dialog about two factors of critical importance to clients

and counselors, the alliance and the outcome.

Using the Measures: A Brief Illustration

The SRS and ORS are practical because they are brief, valid, and promote dialogue with clients about important aspects of treatment. Because their

utility hinges on competent, client-directed integration, the following script is

provided as guidance:

Counselor: I have a couple of short forms that I ask clients to complete, one near the beginning of each session and one near the end.

These forms help us keep track of how things are improving or not

improving in your life and also how our sessions are going. Does that

sound okay?

Client: Sure.

Counselor [giving the client the ORS]: This one focuses on important areas of your life that could improve. I’ll keep track of these over

time so we can see how things are changing or not changing. Since

this is our first meeting, today’s score will rate how things have been

going up until now. Just put a mark on each of these lines showing

how things are going in these four areas of your life, lower scores to

the left and higher scores to the right. Make sense?

Client: Sounds good to me. [Client completes the ORS.]

The counselor then scores the ORS using a metric ruler and can use the ORS

score to open the session by simply acknowledging areas the client scored as

particularly high or low. Opening these dialogues may sound something like,

“I noticed you scored this section lower than the others. Can you tell me more

50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alliancearticleshawmurray2-140121120834-phpapp02/85/Monitoring-Alliance-and-Outcome-with-Client-Feedback-Measures-8-320.jpg)

![Monitoring Alliance and Outcome

about what is most troublesome here?” or “This area continues to be highly rated

for you. Tell me more about what is going well here.” As the session unfolds it is

important to connect client presenting problems to scores on the ORS.

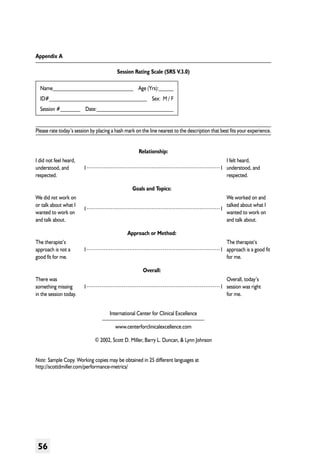

Near the end of each session the counselor engages the client about the

alliance via the SRS:

Counselor: I’d like to ask you to fill out one more brief form before

we end our session today. This one is to help us understand how our

sessions might be adjusted to improve our work together. I really

want any feedback you have. You should know that I’m not looking

for a perfect score. I know that life isn’t perfect and neither am I.

This will help me adjust things here to make sure you get the most

from our time together, so I’d appreciate any feedback you can give

about today’s session. If something wasn’t quite right for you I won’t

take it personally and I can handle the feedback. Like the first form,

this one has four scales. Make a mark on each line showing how you

felt about today’s session. Again, mark lower scores toward the left

and higher scores toward the right. Also, like the first form, we will

spend a little time talking about your ratings. Any questions?

Client: No. Seems pretty clear. (Client completes the SRS.)

Counselor: Thanks for taking time to think about each of these

scales before marking down a score [counselor acknowledges the

client’s thoughtfulness and care in completing the form]. How you

feel about our sessions is really important to me. [Counselor quickly

scores the SRS.] I notice that you scored the “goals and topics” scale

a bit lower than the others. Can you tell me a little more about what

wasn’t quite right there?

Client: Well, you listened really well and I felt understood by you.

I felt like I had so much to talk about with problems at my job that

I just didn’t get around to discussing my boyfriend. We’re arguing a

lot.

Counselor: Thanks so much for telling me that and I’m glad you felt

understood and listened to today. I want to make sure that we are

focusing on topics that are really important to discuss, so I’ll make a

note about your relationship with your boyfriend.

Client: Great. It’s not a real big deal but our arguing is putting a

strain on us and me.

Counselor: Sure, and that strain can impact so much of what’s going

on for you. I’m glad you feel comfortable bringing this up and that

you can tell me where we should focus.

As indicated in these examples, the ORS and SRS are tools for dialog as

well as for tracking progress over time. After several sessions, counselors can

51](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alliancearticleshawmurray2-140121120834-phpapp02/85/Monitoring-Alliance-and-Outcome-with-Client-Feedback-Measures-9-320.jpg)