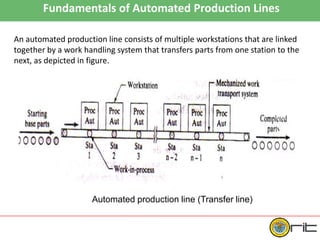

This document discusses automated production lines, also called transfer lines or transfer machines. It provides three key points:

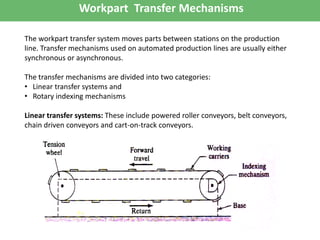

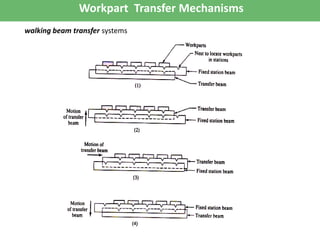

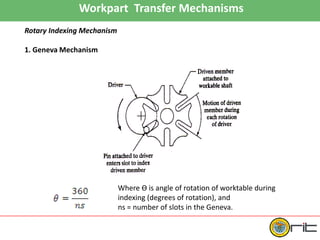

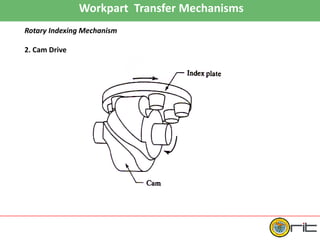

1. Automated production lines consist of multiple linked workstations that perform processing operations like machining on parts. Parts are transferred between stations by a mechanized material handling system.

2. Transfer lines are appropriate for high production demand of parts requiring multiple operations, with stable designs and long product lives. They provide benefits like low labor costs and high production rates.

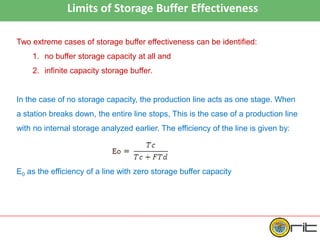

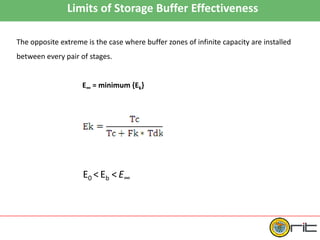

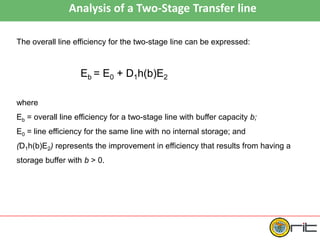

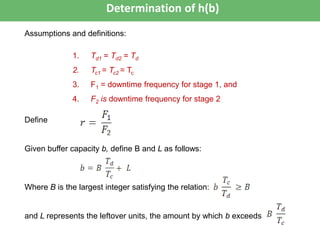

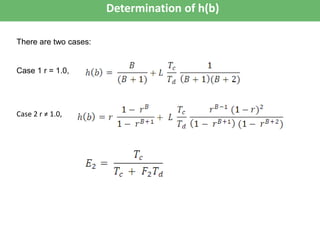

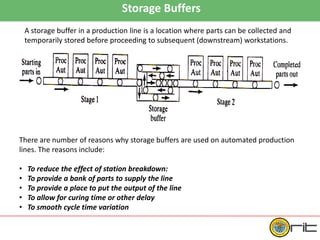

3. Storage buffers between workstations can reduce the impact of breakdowns and allow production to continue. The effectiveness of buffers depends on their capacity, providing some protection even with small buffers but maximum benefits with unlimited capacity buffers.

![Analysis of Transfer Lines

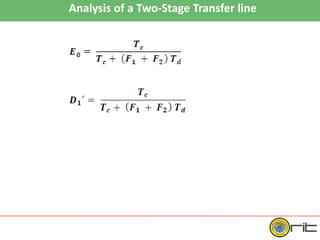

Analysis of Transfer Lines with no Internal Storage

Basic Terminology and Performance Measure

Assumptions

• The workstations perform processing operations such as machining, not

assembly.

• Processing times at each stations are constant, though not necessarily equal.

• Synchronous transfer of lines and

• No internal storage buffers.

Ideal cycle time Tc of the production line, which is the processing time for slowest

station on the line plus transfer time.

Tc = Max [Tsi] + Tr

where Tc = ideal cycle time in min.

Tsi = the processing time at station i in min, and

Tr = transfer time in min.

We use the Max [Tsi] because the longest processing time establishes the pace of

the production line. Remaining stations with lower processing times must wait for

the slowest station. Therefore, these other stations will experience idle time.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aiar-160819080823/85/Aiar-unit-ii-transfer-lines-14-320.jpg)