This document outlines a pediatric epilepsy slide deck presented by the American Epilepsy Society. It covers several key topics:

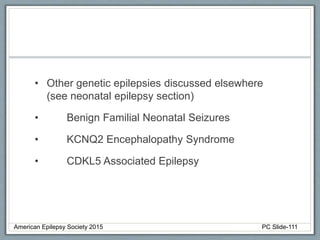

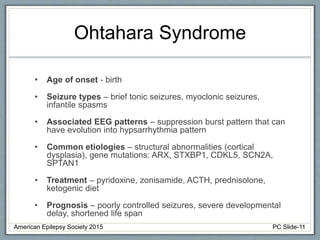

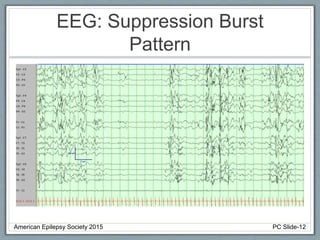

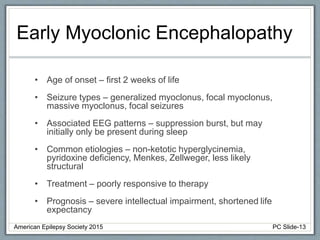

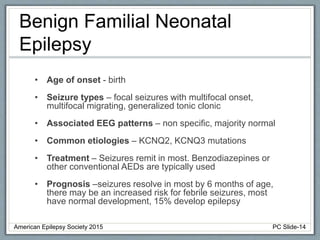

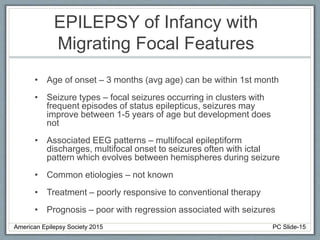

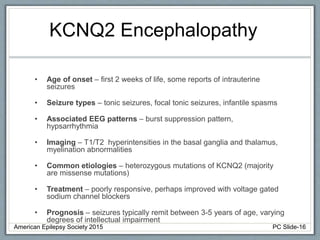

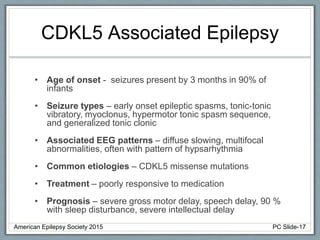

Section 1 discusses seizures and epilepsy syndromes that present in neonates and early infancy, including Ohtahara syndrome, early myoclonic encephalopathy, benign familial neonatal epilepsy, and others.

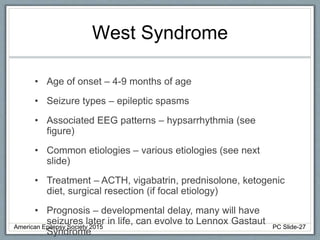

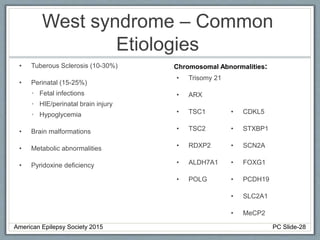

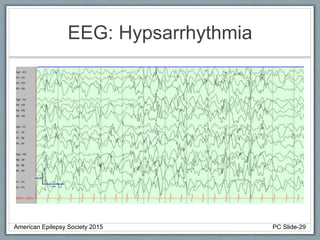

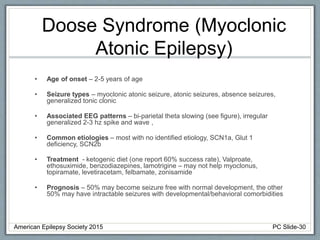

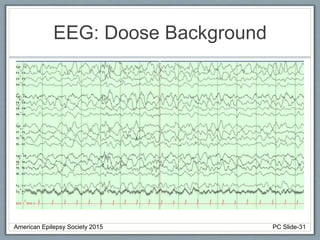

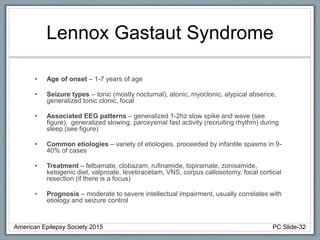

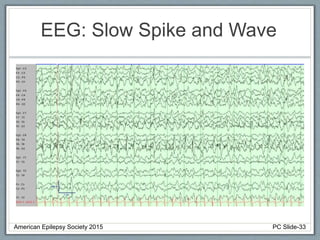

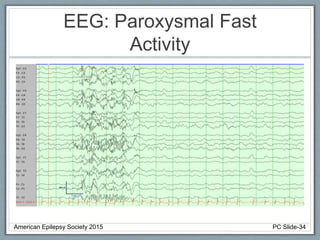

Section 2 covers epilepsy syndromes that present in early childhood and adolescence, such as West syndrome (characterized by epileptic spasms and a hypsarrhythmia EEG pattern), Doose syndrome, and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.

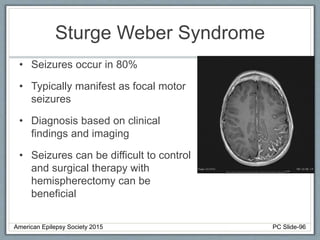

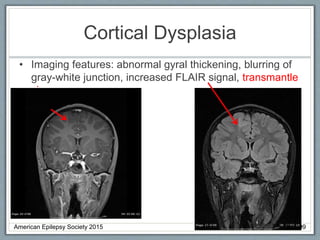

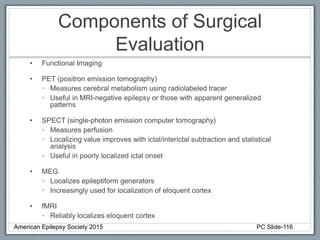

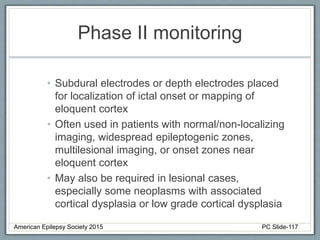

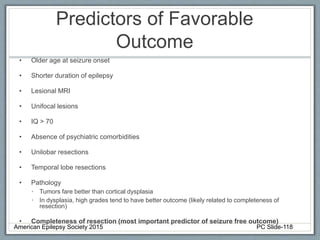

Section 3 describes unique etiologies of epilepsy that often present with pediatric onset. Section 4 discusses surgical evaluation of int

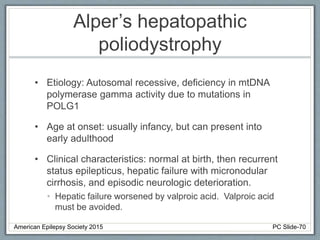

![Alper’s hepatopathic

poliodystrophy

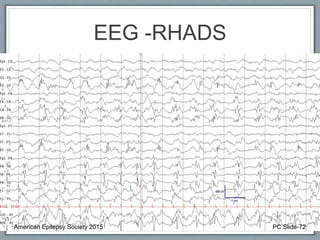

• EEG: Slow or absent posterior dominant rhythm with

multifocal and generalized epileptiform activity.

Rhythmic High Amplitude Delta with Superimposed

Spikes [RHADS] common associated EEG pattern.

(see figure)

• Imaging: Variable, including migratory cortical and

subcortical hyperintensities, basal ganglia and thalami

changes, diffuse white matter changes, cerebellar

atrophy

• Clinical course: progressively worsening epilepsy and

hepatic failure. Death within months to 12 years of

onset.

American Epilepsy Society 2015 PC Slide-71](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aespedworkgroupslidefinal-240307040912-6aae7367/85/AES-Pediatrics-Working-group-Slide-Final-pptx-71-320.jpg)