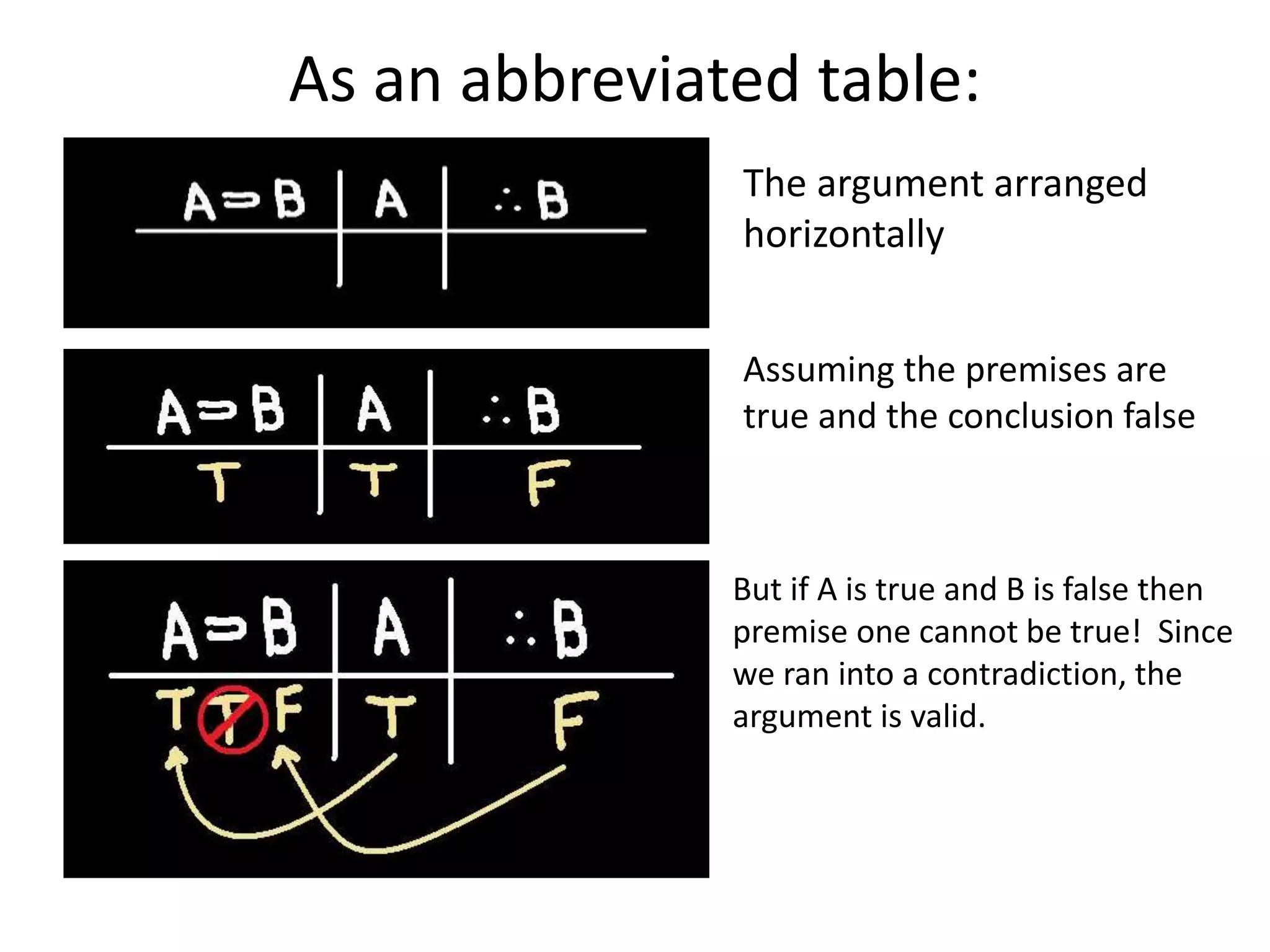

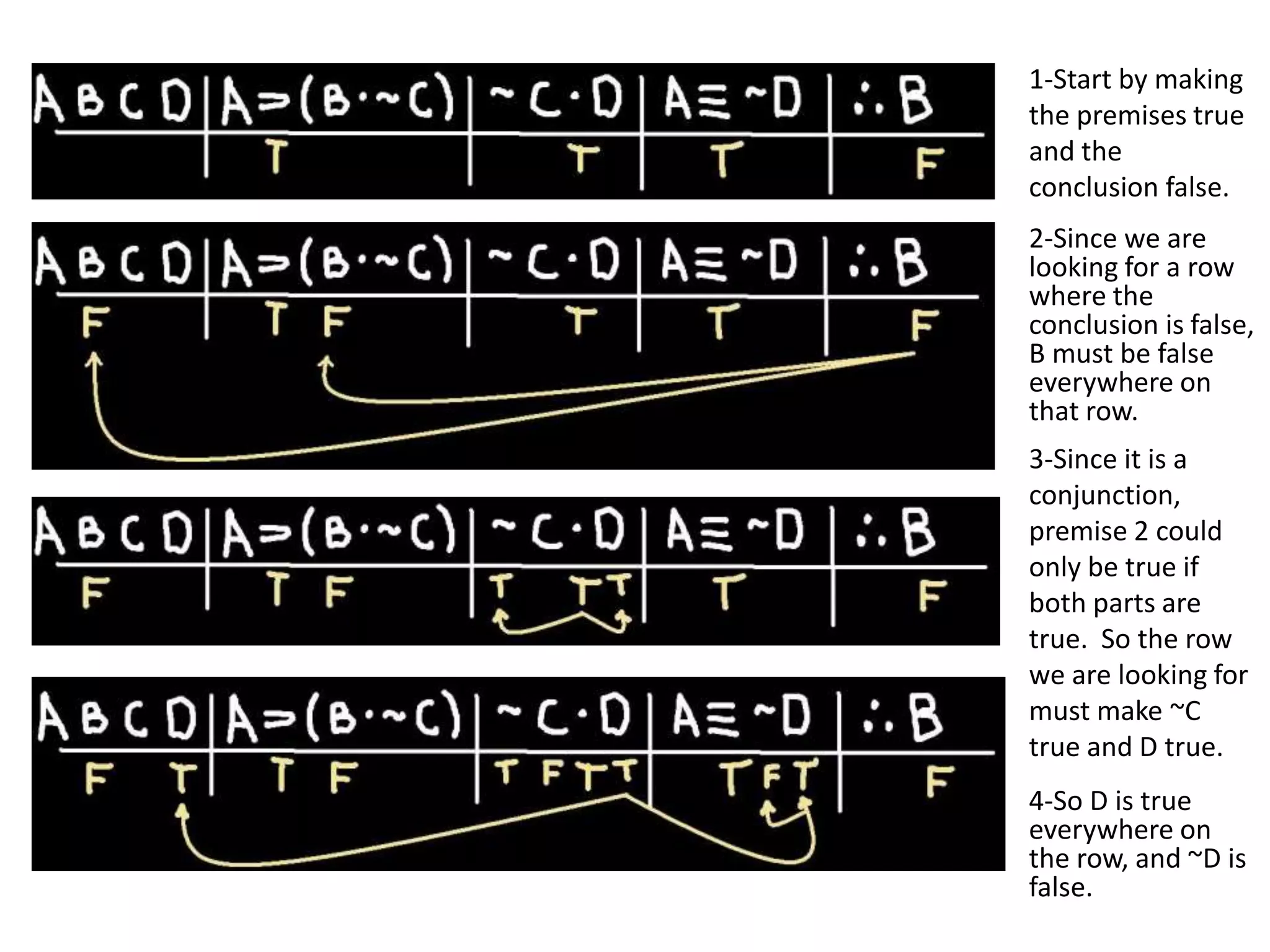

- Abbreviated truth tables check an argument's validity by assuming the premises are true and conclusion is false, working backwards to assign true/false values to statements.

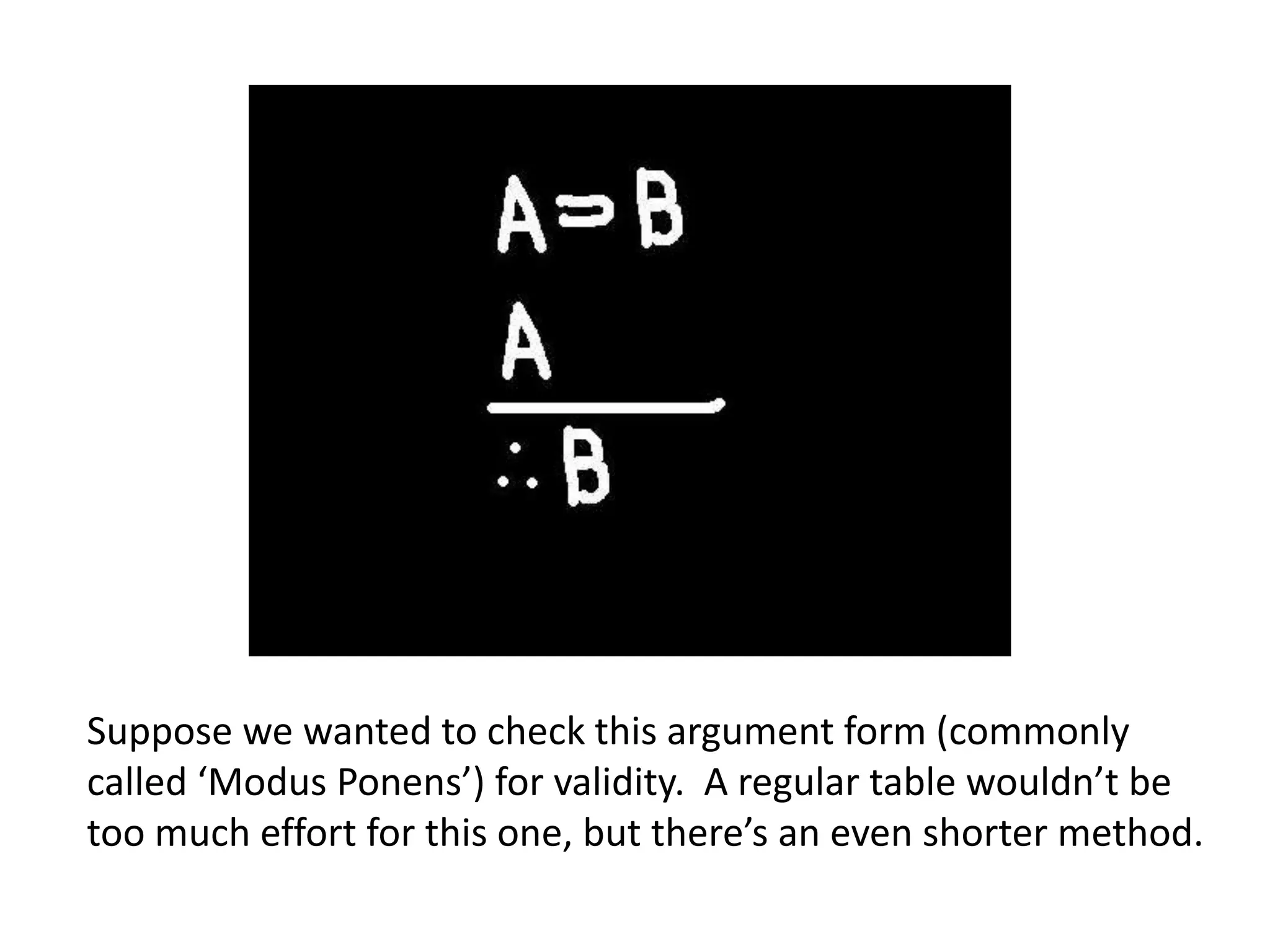

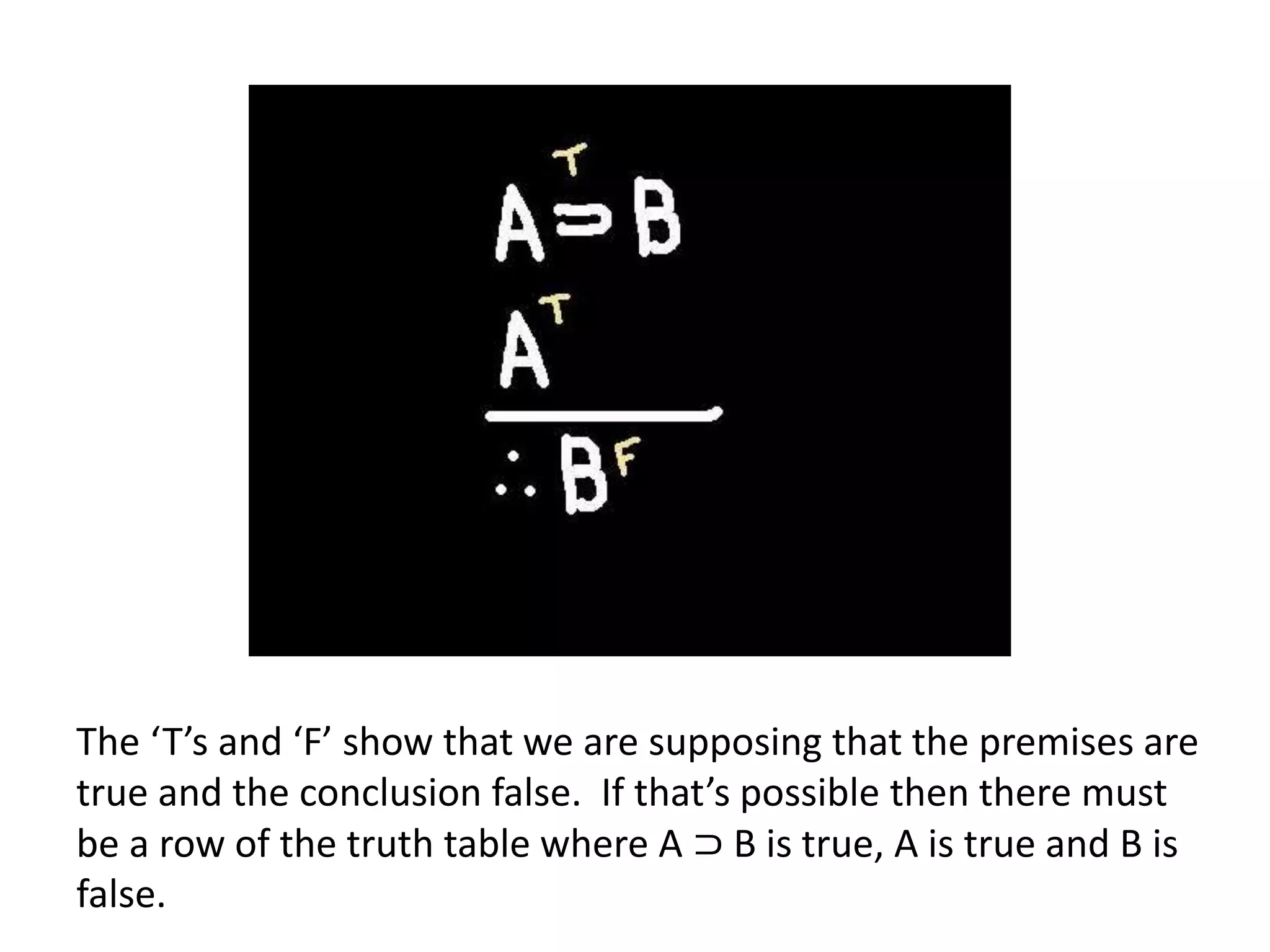

- For the argument "If A then B, A. Therefore B", assuming A is true and B is false leads to a contradiction, showing the argument is valid.

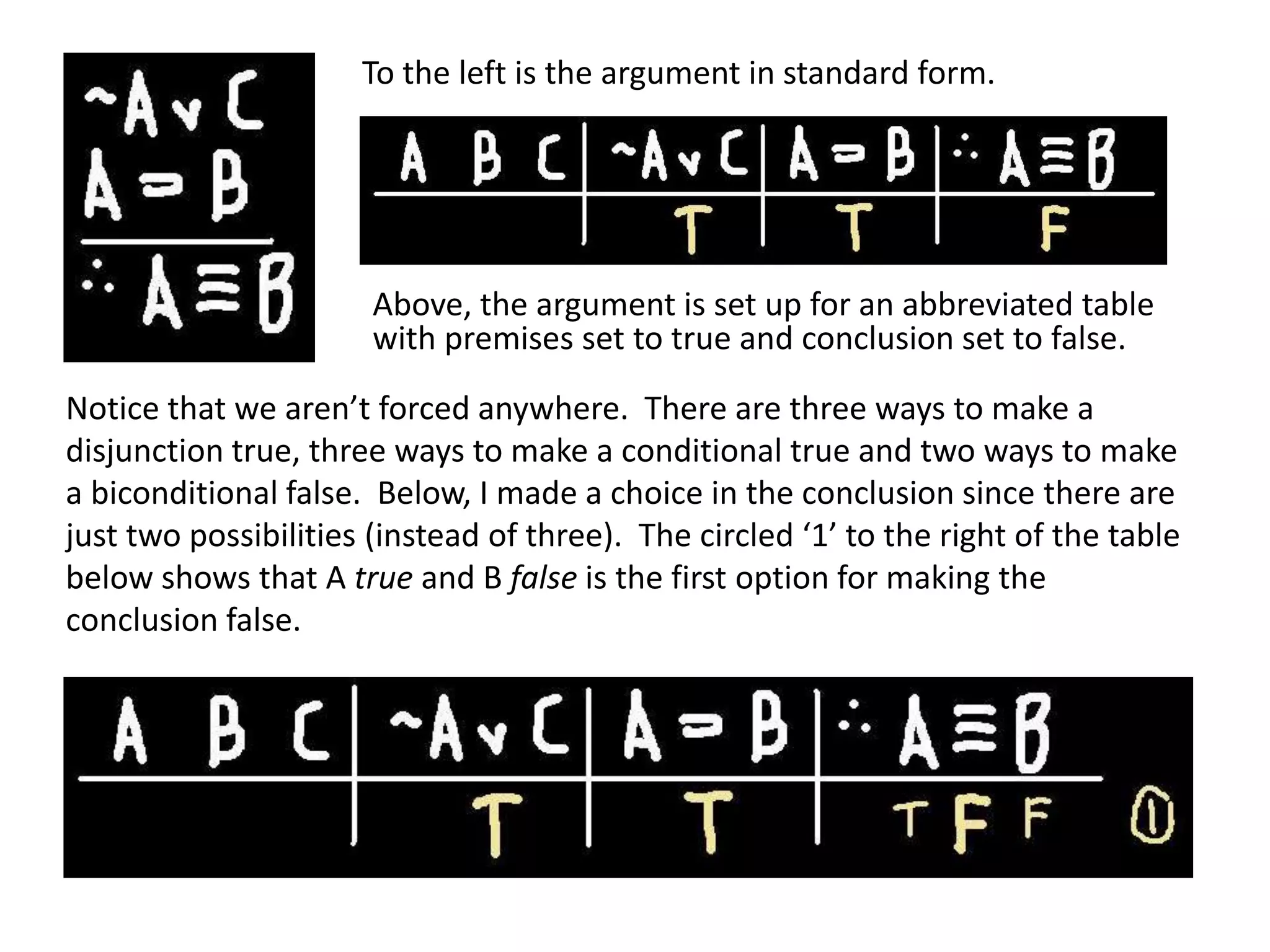

- More complex arguments may involve choices when multiple assignments could satisfy premises/conclusion. Finding a contradiction means that choice leads to a valid argument; an assignment without contradiction means the argument is invalid.