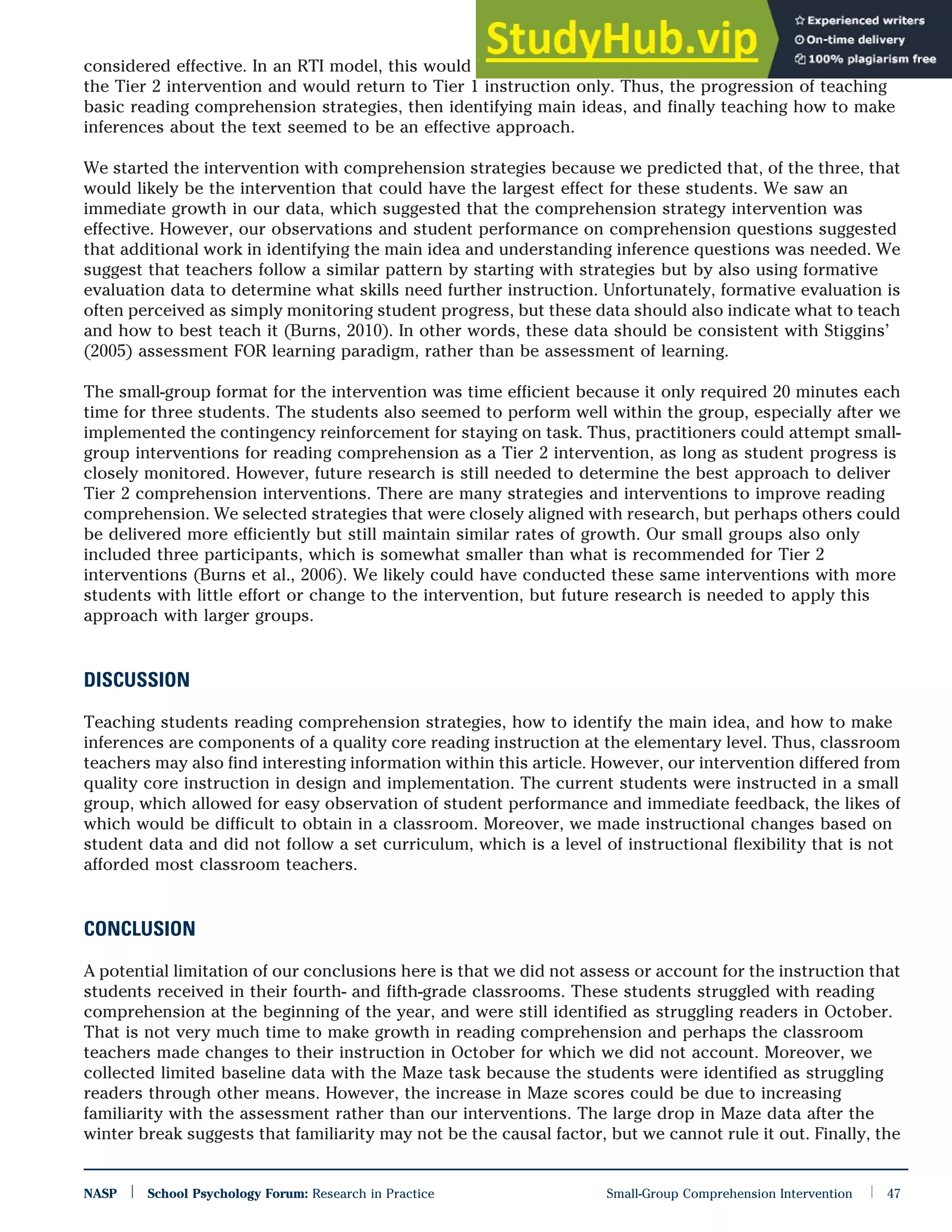

This document summarizes a study that tested a small-group reading comprehension intervention for 4th and 5th grade students. The intervention taught students strategies like prediction, summarization, activating prior knowledge, question generation, and clarification. It also taught students how to understand inferential comprehension questions. 3 students participated in the 20-minute intervention sessions 3 times per week. The intervention began with basic comprehension strategies and moved to teaching main idea identification and inferences. Evaluation data suggested the intervention was successful in improving the students' reading comprehension.

![Although research has supported the effectiveness of RTI approaches in improving reading skills (Burns,

Appleton, & Stehouwer, 2005), the focus of most RTI models is on phonics and reading fluency (Allington,

2008). A focus on code-based interventions may be appropriate for struggling readers in grades K–3, but

fluency interventions for struggling readers in upper elementary years (fourth and fifth grades) may not

be the most appropriate method to remediate reading difficulties. However, there is little research

regarding small-group reading comprehension interventions, the likes of which could be used within an

RTI model.

Reading comprehension occurs when the reader develops mental representations of the text and uses

them to interpret the text (Kintsch & van Dijk, 1978; Pressley & Afflerbach, 1995). Thus, instruction in

reading comprehension is most effective if it develops readers’ understanding of their own cognitive

processes involved in reading, models effective comprehension processes, and allows the reader to

practice the skills necessary to obtain mastery (National Reading Panel [NRP], 2000). Some specific

techniques for comprehension instruction that consistently lead to strong effects and generalization

include the use of graphic organizers, cooperative learning, generating questions after reading,

summarizing, and answering questions as part of a multiple-strategy intervention package (NRP, 2000).

Teaching explicit comprehensions strategies to students has consistently been shown to be effective

(Block, Gambrell, & Pressley, 2002; Pressley, El-Dinary, Wharton-McDonald, & Brown, 1989; Rosenshine &

Meister, 1994; Rosenshine, Meister, & Chapman, 1996), even among children with learning disabilities

(Kavale & Forness, 2000). However, recent research found that comprehension is most affected by

background knowledge and vocabulary, followed in order by correct inferences about reading, word

reading skill, and strategy use (Cromley & Azevedo, 2007). Reciprocal teaching is a comprehension

intervention that teaches strategies such as prediction, summarizing, question generation, and clarifying

(Palinscar & Brown, 1984), but the importance of background knowledge suggests the need to activate

prior knowledge as well (Kintsch, 1994), usually by having the student recall what he or she already

knows about the topic before reading the text (De Corte, Vershaffel, & Van de Ven, 2001). Inferences are

usually accomplished by first identifying the main idea to assure an accurate mental representation of

the text (van den Broek, Lynch, Naslund, Ievers-Landis, & Verduin, 2003), and then teaching relationships

between ideas within the text (Carnine, Silbert, Kame’enui, & Tarver, 2004).

Tier 2 interventions within RTI are generally delivered in a small group, require approximately 30 minutes

each day, and are focused on a specific skill (Burns, Hall-Lande, Lyman, Rogers, & Tan, 2006). The small-

group aspect of a Tier 2 intervention is a potential recipe for success with reading comprehension

because cooperative learning with students in grades 3–6 leads to increases in process and skill while

saving teacher time (NRP, 2000). An effective RTI model depends on a strong Tier 2 intervention system

(Burns & Gibbons, 2008), but the research literature is generally missing small-group interventions for

reading comprehension. Therefore, the current project focused on small-group interventions for students

in fourth and fifth grade that were based on previous reading comprehension research and addressed

reading comprehension strategies, identifying main ideas, and making inferences about the text. The goal

was to implement the interventions and examine their effectiveness as a first step in developing reading

comprehension interventions that could be used within the second tier of an RTI model.

METHODS

The students for the comprehension intervention group were selected because they scored below the

25th percentile on the Measures of Academic Progress (Northwest Evaluation Association, 2003), a group-

administered reading measure, but demonstrated reading fluency scores that were above the 25th

percentile for their grade and time of year on national norms (Hasbrouck & Tindal, 2006). Reading fluency

was used to identify students because word reading skills are related to comprehension (Cromley &

Azevedo, 2007), and selecting students with sufficient word reading skills allowed the interventionists to

focus on background knowledge, inferences, and strategy use rather than word reading. Three students

NASP | School Psychology Forum: Research in Practice Small-Group Comprehension Intervention | 41](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asmall-groupreadingcomprehensioninterventionforfourth-andfifth-gradestudents-230805171017-b48551d0/75/A-Small-Group-Reading-Comprehension-Intervention-For-Fourth-And-Fifth-Grade-Students-2-2048.jpg)