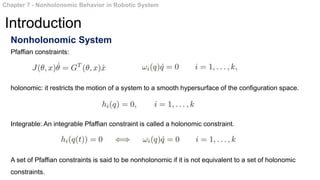

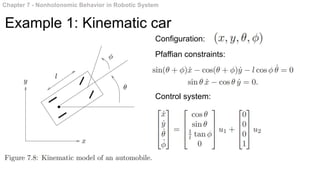

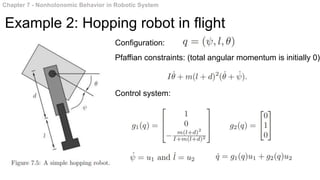

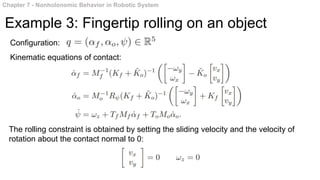

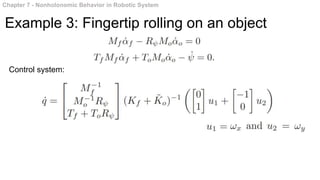

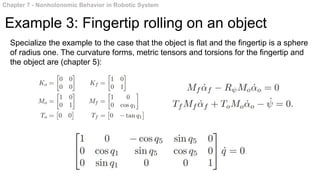

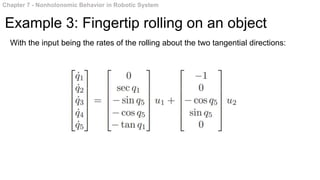

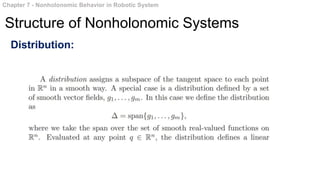

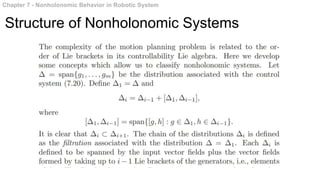

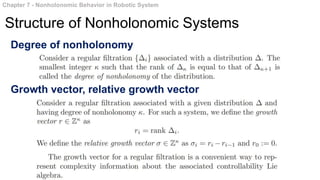

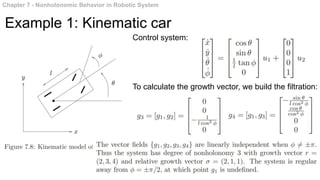

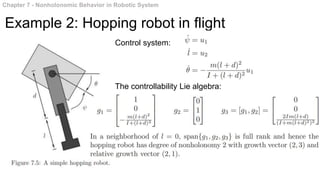

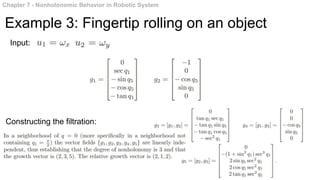

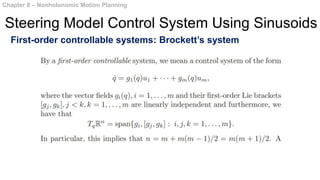

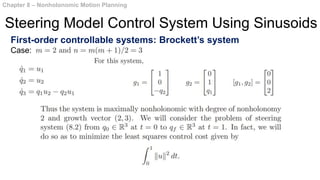

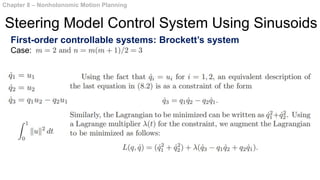

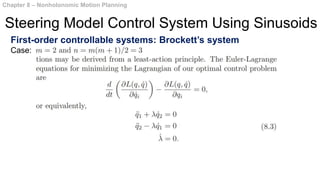

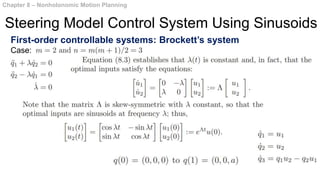

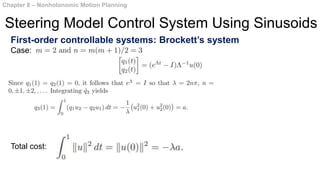

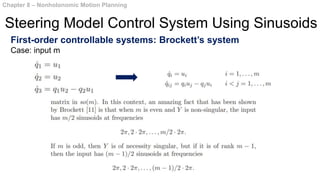

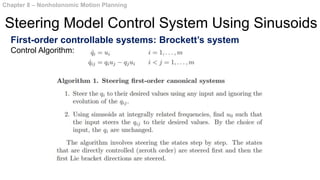

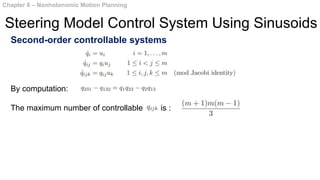

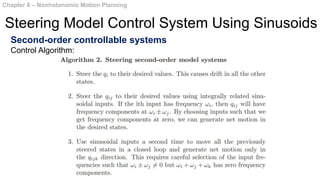

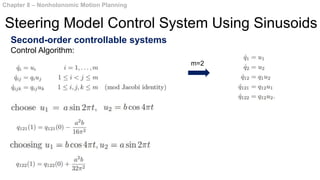

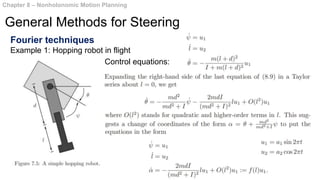

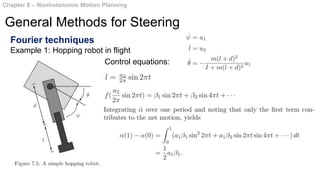

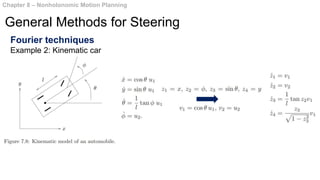

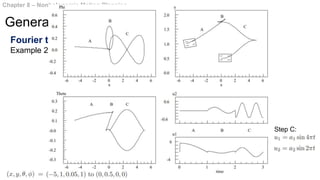

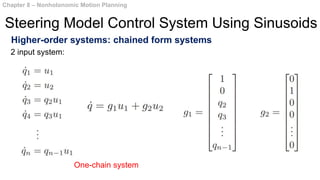

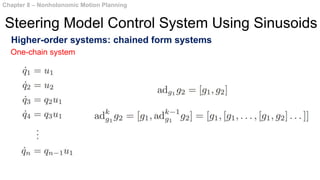

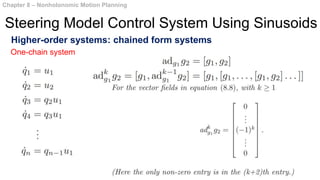

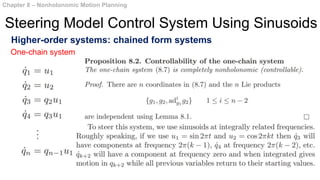

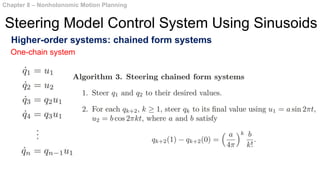

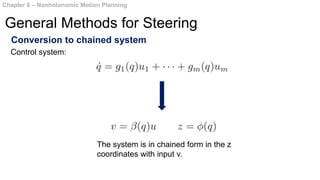

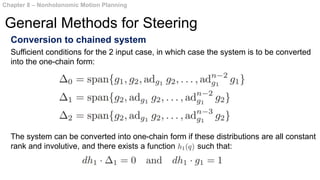

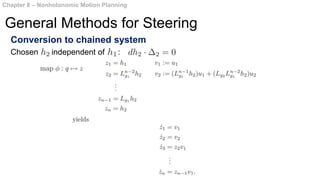

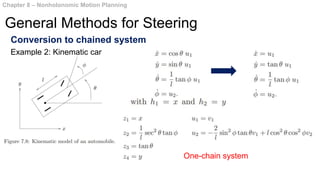

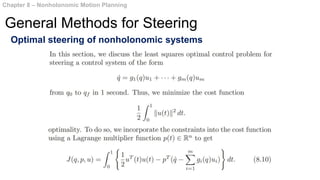

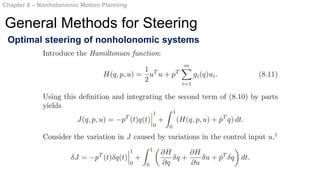

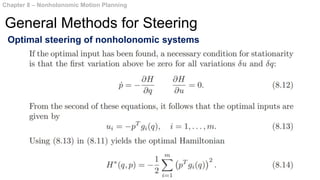

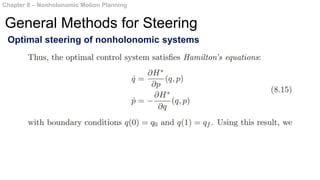

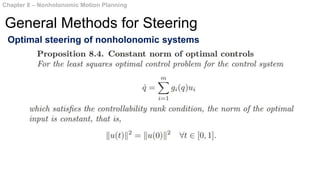

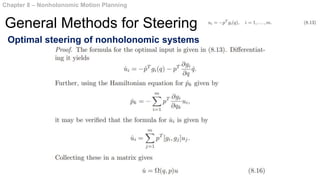

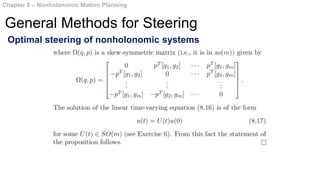

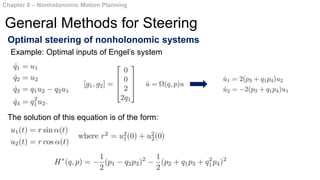

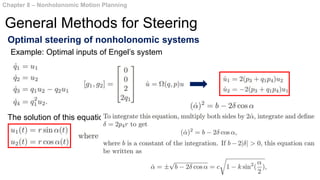

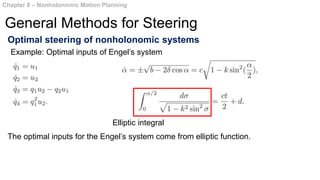

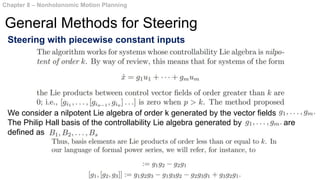

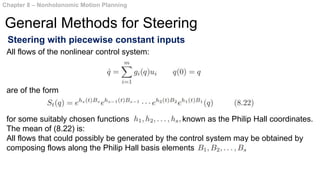

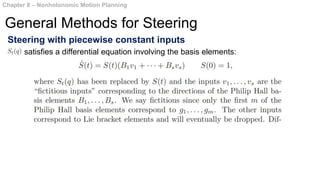

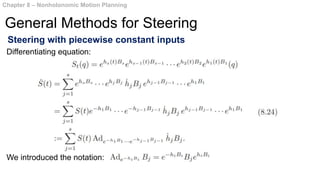

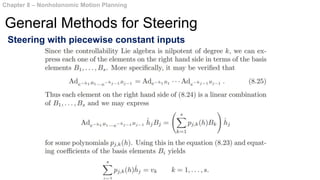

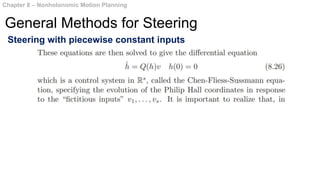

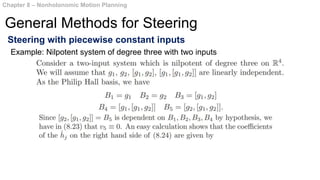

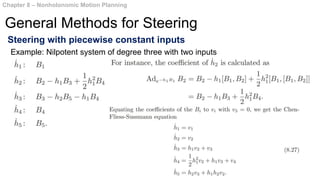

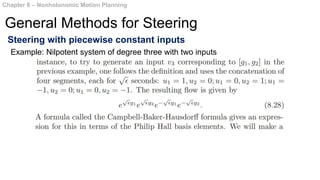

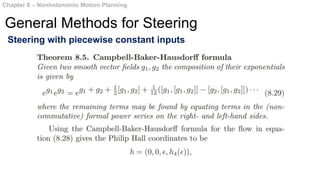

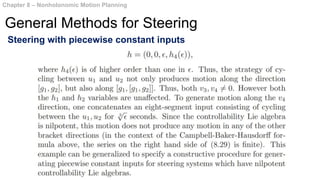

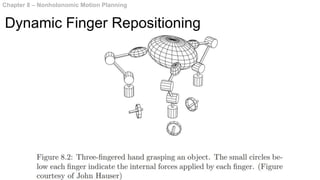

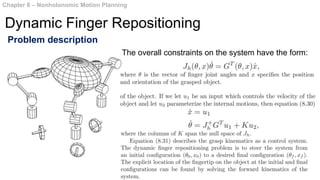

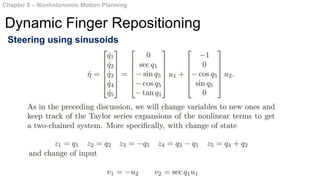

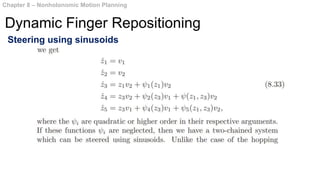

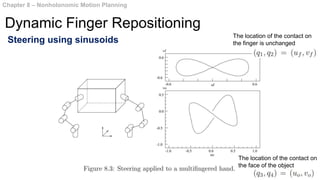

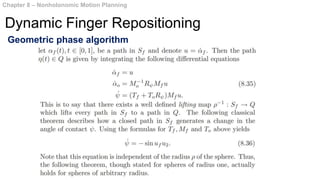

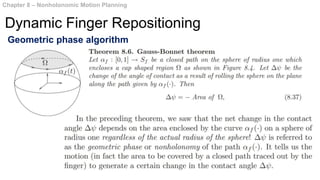

This document summarizes chapters 7 and 8 of a book on nonholonomic motion planning in robotics. Chapter 7 discusses nonholonomic behavior in robotic systems, including examples of nonholonomic systems like cars and robots. It also covers the structure of nonholonomic systems. Chapter 8 describes methods for nonholonomic motion planning, including using sinusoids to steer model systems, general steering methods like Fourier techniques and converting systems to chained form, and optimal steering of nonholonomic systems. It concludes with an example of dynamic finger repositioning using nonholonomic motion planning techniques.