This document presents a model of the job search process based on two character measures - attractiveness and character. Attractiveness is easily observable but character requires an interview. The model considers job seekers deciding whether to apply for jobs and employers deciding whether to invite applicants for interviews. If invited, both parties observe each other's character and decide whether to make an offer/accept. The goal is to find a Nash equilibrium strategy profile satisfying certain criteria like mutual acceptance being required and decisions maximizing expected rewards from search. Multiple equilibria may exist.

![4

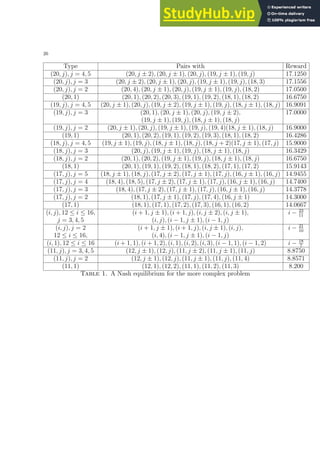

Section 6 presents some results for a larger scale problem, and shows that there may be

multiple equilibria. Section 7 gives a brief conclusion and suggests directions for further

research.

2. The Model

It is assumed that job choice is based on two traits both described by a quantitative

measure. The first will be referred to as ‘attractiveness’ and the second will be referred

to as ‘character’.

We consider a steady state model in which the distributions of the attractiveness (qual-

ifications) and character of a job seeker, as well as of the attractiveness and character

of an employer (denoted X1,js, X2,js, X1,em and X2,em, respectively), do not change over

time.

For convenience, we suppose that X1,es, X1,js, X2,es and X2,js are discrete random

variables which take integer values, and that the attractiveness of a job seeker or employer

is independent of his/her character2

. It will also be assumed that the set of possible

characters of job seekers coincides with the set of possible characters of employers.

The type of an individual can be defined by their attractiveness and character, together

with their role (employer or job seeker). The type of a job seeker will be denoted xjs =

[x1,js, x2,js]. The type of an employer will be denoted xem = [x1,em, x2,em].

Preferences are common with respect to attractiveness, i.e. all job seekers prefer jobs

with a high attractiveness measure3

. Also, preferences are homotypic with respect to

character, i.e., an employer prefers employees with a similar measure of character.

To be more precise, suppose the reward obtained by a type xjs job seeker from taking

a job with a type xem employer is g(x2,js, xem), where g is strictly increasing with respect

to x1,em and strictly decreasing with respect to |x2,js − x2,em|.

Similarly, the reward obtained by a type xem employer from employing a type xjs job

seeker is h(xjs, x2,em), where h is strictly increasing with respect to x1,js, and strictly

decreasing with respect to |x2,js − x2,em|.

The population is assumed to be large.

At each moment n, (n = 1, 2, . . .) each unemployed individual is presented with a

prospective job picked at random. Thus it is implicitly assumed that the operational

ratio of unfilled jobs to job seekers is one, and that individuals can observe as many

prospective jobs as they wish. Suppose the ratio of the number of searching job seekers

to the number of searching employers is r, where r > 1. This situation can be modelled

by assuming that a proportion r−1

r

of employers have attractiveness −∞ (in reality job

seekers paired with such an employer at moment i meet no employer then). An individual

cannot return to a prospective job (or job seeker) found earlier, nor would they want

to, given their preferences and past negative experiences with that prospective employer

(employee).

2In further work we hope to relax this rather restrictive assumption.

3A proxy for which would be the starting wage.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alabourmarketmodelwithmultiplecriteria-230806174725-032a298b/85/A-Labour-Market-Model-With-Multiple-Criteria-4-320.jpg)

![7

Condition 4: The decisions made by an individual do not depend on the moment

at which the decision is made 4

.

In mathematical terms Conditions 1, 2, 3 are necessary and sufficient conditions to

ensure that when the population use the profile πN

, each individual plays according to

a subgame perfect equilibrium in the appropriately defined application/invitation and

interview subgames.

Since the sets of character measures for job seekers and employers coincide, the most

preferred employees of a type [x1,em, x2,em] employer are job seekers of maximum qualifi-

cations who have character x2,em. The most preferred jobs of a type [x1,js, x2,js] employee

are jobs of maximum attractiveness which have character x2,js. Condition 1 states that

in the interview game a job seeker will always accept his/her most preferred job. Several

labour market studies have found empirical evidence that employers and employees are

happiest with labour market choices they view as similar to themselves in some respects

(eg. labour market type, class, educational level), (Peterson et al., 2000; Beller, 1982;

Albelda, 1981).

Condition 4 states that the Nash equilibrium strategy should be stationary. This reflects

the following facts:

1: An individual starting to search at moment i faces the same problem as one

starting at moment 1.

2: Since the search costs are linear, after searching for i moments and not finding

a job, an individual maximises his/her expected reward from search simply by

maximising the expected reward from future search (i.e. by ignoring previously

incurred costs).

Many strategy profiles may lead to the same pattern of applications, interviews and

employment. For example, suppose that there are three levels of attractiveness and char-

acter, which are the same for both employers and employees. Consider π1, the strategy

profile according to which:

a: job seekers apply to employers of at least the same attractiveness;

b: employers are willing to interview job seekers of at least the same attractiveness;

c: in the interview game, individuals of the two extreme characters accept prospec-

tive job matches of either the same character or of the central character;

d: in the interview game individuals of the central character only accept prospective

partners of the same character.

Under π1 only job seekers and employers of the same attractiveness will proceed to

interview. Pairs are only formed between individuals of the same type.

Suppose π2 differs from π1 in that individuals only apply to or invite for interview

prospective partners of the same attractiveness. The pattern of applications, interviews

and pair formation under these two strategy profiles would be the same.

4Again, this is a restrictive assumption we hope to relax in further work.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alabourmarketmodelwithmultiplecriteria-230806174725-032a298b/85/A-Labour-Market-Model-With-Multiple-Criteria-7-320.jpg)

![10

The job seeker and employer both have two possible actions: accept the prospective

partner, denoted a, or reject, denoted r.

As argued above, we may assume that these decisions are taken simultaneously.

Also, we ignore the costs already incurred by either individual, including the costs of

the present interview, as they are subtracted from all the payoffs in the matrix, and hence

do not affect the equilibria in this subgame.

Suppose the job seeker is of type xjs and the employer is of type xem. The payoff matrix

is given by

Employer: a Employer: r

Job Seeker: a

Job Seeker: r

[g(x2,js, xem), h(xjs, x2,em)] [Rjs(xjs; π), Rem(xem; π)]

[Rjs(xjs; π), Rem(xem; π)] [Rjs(xjs; π), Rem(xem; π)]

.

The appropriate Nash equilibrium of this subgame is for the job seeker to accept the job

if and only if g(x2,js, xem) ≥ Rjs(xjs; π) and the employer to accept the job seeker if and

only if h(xjs, x2,em) ≥ Rem(xem; π).

For convenience, we assume that when h(xjs, x2,em) = Rem(xem; π), an employer always

accepts the job seeker (in this case she is indifferent between rejecting and accepting him

for the job). Similarly, if g(x2,js, xem) = Rjs(xjs; π), it is assumed that a job seeker always

accepts an employer.

If a job seeker rejects an employer, then the employer is indifferent between accepting or

rejecting the job seeker. By using the rule given above, an employer will take the optimal

action whenever a job seeker “mistakenly” accepts a job offer.

Under these assumptions, this subgame has a unique Nash equilibrium and value. Let

v(xjs, xem; π) = [vjs(xjs, xem; π), vem(xjs, xem; π)] denote the value of this game, where

vjs(xjs, xem; π) and vem(xjs, xem; π) are the values of the game to the job seeker and

employer, respectively.

We now consider the application/invitation game.

4.2. The Application/Invitation Subgame. Once the interview subgame has been

solved, we may solve the application/invitation subgame and hence the game G(xjs, xem; π).

As before, we assume that the population is following a strategy profile π.

The possible actions of a job seeker are n — do not apply for a job and a — apply for

the job. The possible actions of a potential employee are i - invite for interview and r -

reject an application.

These actions are based on the attractiveness of the prospective partner. As before, we

may ignore the costs that have been previously incurred. Since the order in which the

actions are taken is important, we must consider the extensive form of this game, which

is given below.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alabourmarketmodelwithmultiplecriteria-230806174725-032a298b/85/A-Labour-Market-Model-With-Multiple-Criteria-10-320.jpg)

![11

✠

❅

❅

❅

❅

❅

❅

❘

Job Seeker: n Job Seeker: a

[Rjs(xjs; π), Rem(xem; π)]

✠

Employer: r

❆

❆

❆

❆

❆

❆

❯

Employer: i

[Rjs(xjs; π) − c3,js, Rem(xem; π)] v(xjs, xem; π) − (c2,js + c3,js, c2,em)

Fig. 1: Extensive form of the application/invitation game.

Here, v(xjs, xem; π) = [vjs(xjs, x1,em; π), vem(x1,js, xjs; π)] denotes the expected value

of the interview game given the strategy profile used by the population, the measures

of attractiveness of the pair, and the fact that an interview followed. In defining these

payoffs, it is assumed that the players are following the appropriate strategy from the

strategy profile π. The calculation of the expected rewards when one individual deviates

from this profile is considered in Section 5.

It should be noted that when a job seeker makes his decision he has no information

regarding the character of an employer.

However, the fact that a job seeker applies for a job may implicitly give the employer

some information regarding his character.

Suppose that under the strategy profile π, the decision of a job seeker of qualifications

x1,js on whether to apply for a job of attractiveness x1,em does not depend on the character

of the job seeker.

The posterior distribution of the character of such a job seeker, given that an application

has been received is simply the marginal distribution of the character of such a job seeker.

In this case, an employer obtains no information on the character of the job seeker, and

we say that the decision of the job seeker is non-revealing (with respect to the character

of the job seeker).

However, if the population has evolved to some equilibrium, the evolutionary process

will have implicitly taught job seekers which type of employers will invite them for inter-

view and which will wish to employ them. This is recursive learning along the lines of

(Velupillai, 2000, Chapter 5), and Spear (1989).

Hence, we assume that job seekers implicitly know the conditional distribution of the

character of the employer given that an interview takes place.

A strategy profile π is said to be non-revealing if the decision of any individual on

whether to apply for a job or invite for interview, as appropriate, is only dependent on

that individual’s attractiveness and not his/her character.

The application/invitation game must be solved by recursion. The employer only has

to make a decision in the case where the job seeker has applied. She should invite for

interview if and only if her expected reward from interviewing is at least as great as the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alabourmarketmodelwithmultiplecriteria-230806174725-032a298b/85/A-Labour-Market-Model-With-Multiple-Criteria-11-320.jpg)

![12

expected reward from future search, i.e.

vem(x1,js, xem; π) − c2,em ≥ Rem(xem; π).

If no employer of the attractiveness observed wishes to invite the job seeker for interview,

then the job seeker should not apply.

Otherwise, the job seeker should apply if

r(x1,js, x1,em; π)[vjs(xjs, x1,em; π)−c2,js]+(1−r(x1,js, x1,em; π)Rjs(xjs; π)−c3,js ≥ Rjs(xjs; π),

where r(x1,js, x1,em; π) is the probability that a randomly chosen employer of attractiveness

x1,em wishes to invite a job seeker of qualifications x1,js for interview.

We now present an algorithm to solve such a game, as an algorithmic game in the

tradition of Velupillai (1997); Nisam et al. (2007).

5. An Algorithm to Derive a Subgame Perfect Equilibrium

The algorithm proposed to find a Nash equilibrium of the game satisfying Conditions

1-4 starts by assuming that:

1: job seekers of the highest level of attractiveness will only apply for jobs of the

highest level of attractiveness and they will be invited for interview by such em-

ployers.

2: job seekers and employers of maximum attractiveness only form pairs with others

of the same character (remember that it is assumed that the sets of possible

characters for these groups coincide).

It should be noted that this will be part of a Nash equilibrium profile when the search

and interviewing costs are sufficiently small. This follows from the following argument:

For sufficiently small costs, job seekers of maximum qualifications only wish to take a job

with their preferred type of ‘partner’ (i.e. jobs of maximum attractiveness with the same

character). Similarly, employers are only willing to offer jobs of maximum attractiveness

to job seekers of maximum attractiveness and the same character.

It should be noted that if at equilibrium a job seeker of type [i, j] is willing to apply

for a job of attractiveness k, then he must be willing to accept a job of type [k, j] in the

interview game. This is due to the fact that a job seeker of type [i, j] would not apply for

such a job, if he were not willing to take any job of attractiveness k, and type [k, j] jobs

are the most preferred jobs in this group. Similarly, if an employer of type [i, j] is willing

to invite a job seeker of attractiveness k for interview, he must be willing to offer a job

to a job seeker of type [k, j].

We can calculate the expected rewards of individuals of maximum attractiveness under

the initial strategy profile. We then iteratively improve the payoffs of job seekers and em-

ployers of maximum qualifications by changing the patterns of applications, interviewing

and job pairings as follows:

1: At each stage extend the set of acceptable jobs of all job seekers of maximum

qualifications by increasing the acceptable difference in character by 1 or decreasing](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alabourmarketmodelwithmultiplecriteria-230806174725-032a298b/85/A-Labour-Market-Model-With-Multiple-Criteria-12-320.jpg)

![14

of acceptable jobs or acceptable employees, as appropriate. The algorithm then continues

as before. Since the algorithm attempts to maximise the expected reward of an individ-

ual, given the behaviour of individuals of relatively higher attractiveness, the pattern of

applications, interviews and job pairings that results from this procedure will, in general,

be very similar to the pattern of applications, interviews and job pairings that results

from a Nash equilibrium strategy profile.

It should also be noted that the “strategy profiles” considered in this algorithm are not

fully defined strategy profiles. Only the pattern of applications, interviews and job pairings

are defined. Once the algorithm has converged, we use the policy iteration algorithm to

check whether the proposed pattern corresponds to a Nash equilibrium of the required

form and, if so, fully define the strategy profile.

We illustrate this algorithm with an example.

5.1. Example. Suppose that among both employers and job seekers there are 2 levels

of attractiveness, X1 ∈ {2, 3}, and three levels of character X2 ∈ {0, 1, 2}. Each of the

six possible types are equally likely. The search costs for both job seekers and employers,

denoted c1, are 0.3. The costs of interviewing for an employer, c2,em, are 0.25. The costs

of applying for a job are c3,js = 0.1 and the costs of a job seeker going for an interview

are c2,js = 0.15.

The reward obtained by a type [i, j] individual forming a job pairing with a type [k, l]

individual is assumed to be k − |j − l| (for both job seekers and employers).

We initially assume that job seekers of maximum attractiveness only apply for jobs

of maximum attractiveness and only accept jobs with the same character. Employers of

maximum attractiveness only invite job seekers of maximum attractiveness for interview

and only offer jobs to job seekers of the same character. It follows that the expected

length of search of such individuals is 6 and the number of interviews (and applications)

is 3. Since a job seeker’s costs for applying and going to an interview are equal to the

employer’s interview costs, the expected reward gained under such a profile (labelled π0) is

independent of an individual’s role (employer or job seeker). It follows that for y = 0, 1, 2

Rem([3, y]; π0) = Rjs([3, y]; π0) = 3 − 0.3 × 6 − 0.25 × 3 = 0.45.

We now consider expanding the set of types of job acceptable to a job seeker of maximum

attractiveness.

From the form of the payoff function, and the distribution of types, it is of greater

benefit for such a job seeker to accept jobs of attractiveness 3 with a neighbouring level of

character (such a strategy profile will be denoted π1), rather than jobs of attractiveness

2 with the same character.

This follows from the fact that the reward from taking either type of job would be the

same, but only applying for jobs of attractiveness 3 does not increase the expected costs

incurred in applications/interviews.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alabourmarketmodelwithmultiplecriteria-230806174725-032a298b/85/A-Labour-Market-Model-With-Multiple-Criteria-14-320.jpg)

![15

The reward obtained by any job seeker of maximum attractiveness, is greater under a

strategy profile of the form π1 (given the relevant employers find the job seekers acceptable)

than the expected reward under π0.

From the ”symmetry” of the problem, the newly acceptable employers would also find

the job seekers acceptable. Hence, the sets of jobs acceptable to job seekers of attractive-

ness 3 should be extended, along with the sets of job seekers acceptable to employers of

attractiveness 3. After such an extension

1: Type (3, 0) individuals (both job seekers and employers) pair with type (3, 0) and

(3, 1) individuals.

2: Type (3, 1) individuals pair with type (3, 0), (3, 1) and (3, 2) individuals.

3: Type (3, 2) individuals pair with type (3, 1) and (3, 2) individuals.

The expected payoffs of individuals of attractiveness 3 under such a profile π1 are given

by

R•([3, 0]; π1) = R•([3, 2]; π1) = =

1

2

(2 + 3) − 0.3 × 3 − 0.25 ×

3

2

= 1.225

R•([3, 1]; π1) =

1

3

(2 + 3 + 2) − 0.3 × 2 − 0.25 ≈ 1.4833,

where • stands for either js or em.

We now check whether a type (3, 1) job seeker can gain by accepting type (2, 1) jobs.

Note that a type (3, 0) job seeker cannot gain by accepting a type (3, 2) job, as the reward

obtained from taking such a job is less than Rjs([3, 0]; π1). Hence, we must only check

whether type (3, 0) job seekers can gain by accepting type (2, 0) jobs. If so, by symmetry

type (3, 2) job seekers can gain by accepting type (2, 2) jobs. Under such a profile, π2,

job seekers of attractiveness 3 would be willing to apply for any prospective job. Since

employers of attractiveness 2 have not yet become acceptable to any job seeker, it is clear

that in this case such employers increase their expected reward from search by accepting

the job seekers under consideration. Hence, under π2 job seekers of type [3, 0] apply for

all positions, are interviewed for all positions and pair with employers of type (3, 0), (3, 1)

and (2, 0). Hence, the expected length of search, as well as the expected number of

both applications and interviews, is equal to 2. Job seekers of type [3, 1] apply for any

position, are always interviewed and pair with employers of type (2, 1), (3, 0), (3, 1) and

(3, 2). The expected length of search, as well as the expected number of both interviews

and applications, is equal to 3

2

. Using symmetry with respect to the central character,

the expected rewards of job seekers of attractiveness 3 under π2 are given by

Rjs([3, 0]; π2) = Rjs([3, 2]; π2) =

1

3

(2 + 3 + 2) − 0.3 × 2 − 0.25 × 2 ≈ 1.2333

Rjs([3, 1]; π2) =

1

4

(2 + 3 + 2 + 2) − 0.3 ×

3

2

− 0.25 ×

3

2

≈ 1.425.

Hence, type (3, 0) job seekers should accept type (2, 0) jobs, but type (3, 1) job seekers

should not accept type (2, 1) jobs. Let π3 be the corresponding profile.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alabourmarketmodelwithmultiplecriteria-230806174725-032a298b/85/A-Labour-Market-Model-With-Multiple-Criteria-15-320.jpg)

![16

Since the expected payoffs of job seekers of attractiveness 3 are greater than can be

obtained by accepting any type of job not yet considered, Steps 1 and 2 are concluded.

We now consider extending the sets of job seekers acceptable to employers. From the

earlier calculations employers of attractiveness 3 should accept job seekers of attractiveness

3 with a neighbouring character. Using the symmetry of the problem, it follows that type

(3, 0) employers should accept type (2, 0) job seekers and type (3, 2) employers should

accept type (2, 2) job seekers.

We now consider whether job seekers of attractiveness 2 should be willing to apply for

jobs of attractiveness 3. Since job seekers of attractiveness 2 are only invited for interview

by employers of type (3, 0) and (3, 2) and such employers will not offer a job to a job

seeker of type (2, 1), it follows that job seekers of type (2, 1) should not apply for jobs of

attractiveness 3. Similarly, an employer of type (2, 1) should not invite an individual of

attractiveness 3 for an interview.

Denote this new profile by π4. Under such a profile, when an employer of attractiveness

3 invites a job seeker of attractiveness 2 for an interview, the conditional distribution of

the character of either is as follows: 0 with probability 1

2

and 2 with probability 1

2

.

Now consider the best response of employers of attractiveness 3. Employers of type

(3, 1) should not accept job seekers of type (2, 0) and (2, 2) and thus not invite job seekers

of attractiveness 2 for interview. Employers of type (3, 0) should still invite job seekers

of attractiveness 2 for an interview, as it is more likely under π4 than under π3 that the

job seeker will be of the only acceptable corresponding type. Similarly, the best response

of job seekers of attractiveness 3 is as derived in Step 1. Under π4, job seekers of type

(3, 0) apply for all jobs, are not interviewed only by type (2, 1) employers and pair with

employers of type (3, 0), (3, 1) and (2, 0). Employers of type (3, 0) will interview all job

seekers except those of type (2, 1) and pair with job seekers of type (3, 0), (3, 1) and (2, 0).

We have

Rem([3, 1]; π4) = Rjs([3, 1]; π4) = Rem([3, 1]; π1) ≈ 1.4833

Rem([3, 0]; π4) = Rem([3, 2]; π4) =

1

3

(2 + 3 + 2) − 0.3 × 2 − 0.25 ×

5

3

≈ 1.3167.

Rjs([3, 0]; π4) = Rjs([3, 2]; π4) =

1

3

(2 + 3 + 2) − 0.3 × 2 − 0.15 ×

5

3

− 0.1 × 2 ≈ 1.2833.

We now consider extending the sets of jobs acceptable to job seekers of attractiveness

2. Under π4, job seekers of type (2, 0) apply for jobs of attractiveness 3, are interviewed

by employers of type (3, 0) and (3, 2) and pair with employers of type (3, 0). As of yet,

job seekers of type (2, 1) do not apply for any job. Using symmetry with respect to the

central character, we obtain

Rjs([2, 0]; π4) = Rjs([2, 2]; π4) = 3 − 0.3 × 6 − 0.15 × 2 − 0.1 × 3 = 0.6.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alabourmarketmodelwithmultiplecriteria-230806174725-032a298b/85/A-Labour-Market-Model-With-Multiple-Criteria-16-320.jpg)

![17

Under π4, employers of type (2, 0) interview job seekers of type (3, 0) and (3, 2) and form

pairs with job seekers of type (3, 0). It follows that

Rem([2, 0]; π4) = Rem([2, 2]; π4) = 3 − 0.3 × 6 − 0.25 × 2 = 0.7.

We first consider extending the sets of acceptable jobs to include jobs of the same type

as the job seeker. These are the most preferable jobs of those that have not yet been

considered. Under the resulting strategy profile, π5, job seekers of type (2, 0) apply for all

jobs, are interviewed by all employers except those of type (3, 1) and pair with employers

of type (2, 0) and (3, 0). Job seekers of type (2, 1) only apply for jobs of attractiveness

2, are interviewed for all such positions and pair with employers of type (2, 1). It follows

that

Rjs([2, 0]; π5) = Rjs([2, 2]; π5) =

1

2

(2 + 3) − 0.3 × 3 − 0.15 × 52 − 0.1 × 3 = 0.925

Rjs([2, 1]; π5) = 2 − 0.3 × 6 − 0.25 × 3 = −0.55

Since type (2, 1) employers do not yet accept any type of job seeker, they improve their

expected payoff by accepting type (2, 1) job seekers. By accepting type (2, 0) job seekers,

type (2, 0) employers now interview all job seekers except those of type (3, 1) and pair

with job seekers of type (2, 0) and type (3, 0). Their expected reward from search is given

by

Rem([2, 0]; π5) = Rem([2, 2]; π5) =

1

2

(2 + 3) − 0.3 × 3 − 0.25 ×

5

2

= 0.975.

Hence, the payoffs of employers increase and so the profile is updated to π5.

Since the expected payoffs of all job seekers of attractiveness 2 under π5 are less than

that gained from pairing with an employer of attractiveness 2 with a neighbouring level of

character, the sets of jobs acceptable to them should be extended. Denote the resulting

profile by π6. We have

Rjs([2, 0]; π6) = Rjs([2, 2]; π6) =

1

3

(2 + 3 + 1) − 0.3 × 2 − 0.15 ×

5

3

− 0.1 × 2 = 0.95

Rjs([2, 1]; π6) =

1

3

(1 + 2 + 1) − 0.3 × 2 − 0.25 ≈ 0.4833.

Under such an extension of the strategy profile, type (2, 0) employers interview all job

seekers except those of type (3, 1) and pair with those of type (2, 0), (3, 0) or (2, 1). Type

(2, 1) employers only interview job seekers of attractiveness 2 and will pair with all such

job seekers. It follows that

Rem([2, 0]; π6) = Rem([2, 2]; π6) =

1

3

(2 + 3 + 1) − 0.3 × 2 − 0.25 ×

5

3

= 0.9833

Rem([2, 1]; π6) =

1

3

(1 + 2 + 1) − 0.3 × 2 − 0.25 ≈ 0.4833.

The expected payoffs of employers of attractiveness 2 has increased and thus we update

the strategy profile to π6.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alabourmarketmodelwithmultiplecriteria-230806174725-032a298b/85/A-Labour-Market-Model-With-Multiple-Criteria-17-320.jpg)

![18

Extending the sets of acceptable jobs will not increase the expected reward of any of

these job searchers. Similarly, extending the sets of acceptable employees will not increase

the expected reward of any of the employers.

It follows that π6 is our candidate for a profile of applications, interviews and job pair

formation which corresponds to a Nash equilibrium satisfying Conditions 1-4.

We now use policy iteration to check whether this profile corresponds to a strategy

profile which satisfies the appropriate criteria. First, we consider the interview game.

Each individual (of either role) should accept a prospective job when the reward obtained

from such a pairing is at least as great as the expected reward from future search. It

follows that

1: Type (3, 0) individuals should pair with individuals of type (3, 0), (3, 1) or (2, 0).

2: Type (3, 1) individuals should pair with individuals of type (3, 0), (3, 1), (3, 2) or

(2, 1).

3: Type (3, 2) individuals should pair with individuals of type (3, 1), (3, 2) or (2, 2).

4: Type (2, 0) individuals should pair with individuals of type (2, 0), (2, 1), (3, 0),

(3, 1) or (3, 2). However, acceptance is not mutual in the final two cases.

5: Type (2, 1) individuals should pair with any prospective job, but acceptance is

not mutual when the prospective job is of type (3, 0) or (3, 2).

6: Type (2, 2) individuals should pair with individuals of type (2, 1), (2, 2), (3, 2),

(3, 1) or (3, 0). However, acceptance is not mutual in the final two cases.

We now consider the application/invitation game. This game is solved by recursion

starting with the calculation of the optimal response of an employer to a job seeker of

qualifications i who has applied for a post, where i ∈ {2, 3}.

If under any strategy profile π an employer of attractiveness j invites some job seekers

of qualifications i for an interview, then it is assumed that the distribution of the character

of the job seeker comes from the conditional distribution of character given the invitation

for an interview. An analogous assumption is made with regard to the distribution of the

character of an employer who has invited a job seeker for an interview.

Suppose no job seeker of qualifications i is willing to apply to an employer of attrac-

tiveness j under π. In order to determine the appropriate response of an employer, it is

assumed that the distribution of the character of the job seeker is simply the marginal

distribution of the character of job seekers (i.e. the probability of an individual making a

“mistake” is o(1) and independent of his/her type). Analogous assumptions are made in

the calculation of whether a job seeker should be willing to apply or not.

First consider a type (3, 0) employer who has been applied to by a job seeker of qualifi-

cations 3. Since all job seekers of qualifications 3 are willing to apply to such an employer,

the expected reward from such an interview satisfies

vem([3, 0], 3) =

1

3

[3 + 2 + Rem([3, 0]; π6)] − 0.25 Rem([3, 0]; π6).

Hence, a type (3, 0) employer should invite for interview.

Now suppose a type (3, 0) employer is applied to by a job seeker of qualifications 2.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alabourmarketmodelwithmultiplecriteria-230806174725-032a298b/85/A-Labour-Market-Model-With-Multiple-Criteria-18-320.jpg)

![19

Such a job seeker is of type (2, 0) with probability 1

2

, otherwise he is of type (2, 2). It

follows that the expected reward from inviting such a job seeker for interview is

vem([3, 0], 2) =

1

2

[2 + Rem([3, 0]; π6)] − 0.25 Rem([3, 0]; π6).

Hence, a type (3, 0) employer should invite for interview. It follows from the symmetry

with respect to character that type (3, 2) employers should invite any job seeker for

interview.

Using a similar procedure, it can be shown that type (3, 1) employers should only

invite job seekers of qualifications 3 for interview. Type (2, 0) and type (2, 2) employers

should invite any job seeker and type (2, 1) employers should only invite job seekers of

qualifications 2. Note that since no job seeker of qualifications 3 who is prepared to apply

to an employer of qualifications 2 will pair with an employer of type (2, 1), such employers

should reject the application of a job seeker of qualifications 3.

Now consider the optimal action of a job seeker given the response of an employer

defined above. Any employer of attractiveness 3 will invite a job seeker of qualifications

3 for interview. Hence, by applying to such an employer, a job seeker of type (3, 0) has

an expected reward of 1

3

[3 + 2 + Rjs([3, 0]; π6)] − 0.25. This reward is Rjs([3, 0]; π6).

Hence, a type (3, 0) job seeker should apply to an employer of attractiveness 3. Similarly,

job seekers of type (3, 1) and type (3, 2) should apply to an employer of attractiveness 3.

Now consider whether a job seeker of type (3, 0) should apply to an employer of at-

tractiveness 2. Employers of type (2, 1) will reject such an application, only application

costs are incurred and the future expected reward of the job seeker (including these

costs) is Rjs([3, 0]; π6) − c3,js. Employers of type (2, 0) and (2, 2) will invite such a job

seeker for interview, and the future expected rewards of the job seeker in these cases are

2 − c2,js − c3,js = 1.75 and Rjs([3, 0]; π6) − c2,js − c3,js, respectively. It follows that the

expected reward obtained from applying in this case is 1

3

[1.75 + 2Rjs([3, 0]; π6) − 0.35] ≈

1.3222 Rjs([3, 0]; π6).

Hence, a job seeker of type (3, 0) should apply to an employer of attractiveness 2.

Arguing similarly, job seekers of type (3, 2) should apply to employers of attractiveness 2,

but job seekers of type (3, 1) should not.

In a similar way, it can be shown that job seekers of type (2, 0) or (2, 2) should apply to

any employer and job seekers of type (2, 1) should only apply to employers of attractiveness

2.

The strategy constructed in this way defines a subgame perfect equilibrium in the

game G(xjs, xem; π6). Also, it can be seen that this strategy leads to the same pattern of

applications, interviews and job pairings as under π6. One interesting aspect of the full

description of this strategy profile is that (3, 1) individuals would pair with type (2, 1)

individuals in the interview game, but the marginal gain of such a pairing is not large

enough to ever justify the costs of a type (3, 1) job seeker applying to an employer of

attractiveness 2, or a type (3, 1) employer inviting a job seeker of attractiveness 2 for an

interview.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alabourmarketmodelwithmultiplecriteria-230806174725-032a298b/85/A-Labour-Market-Model-With-Multiple-Criteria-19-320.jpg)