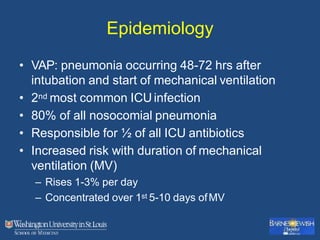

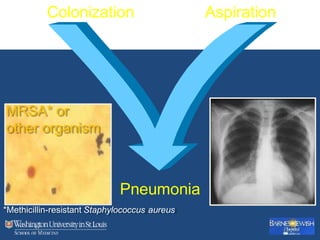

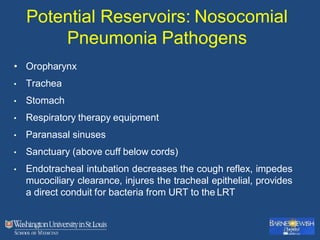

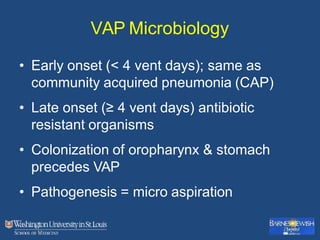

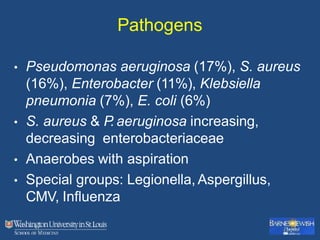

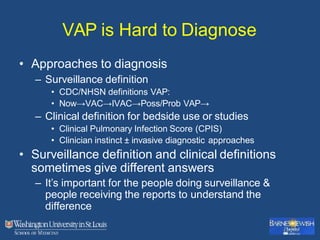

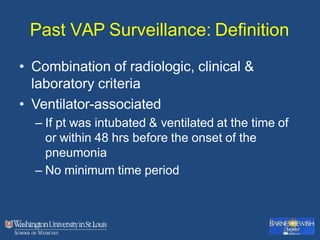

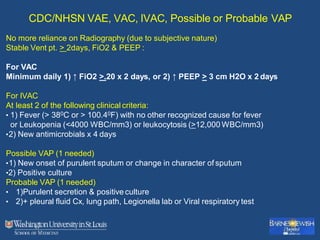

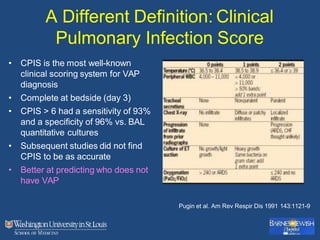

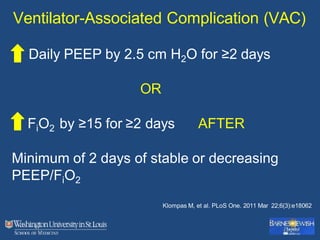

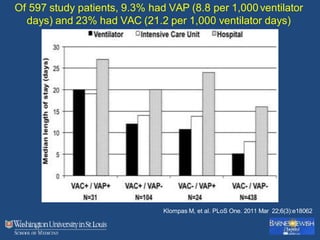

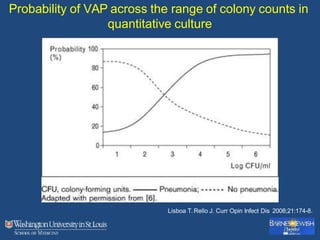

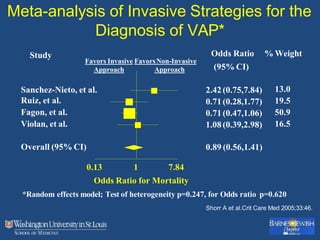

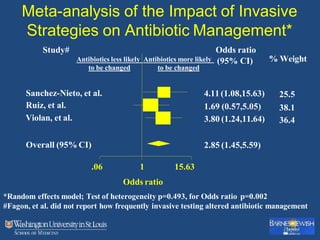

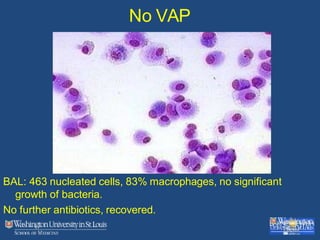

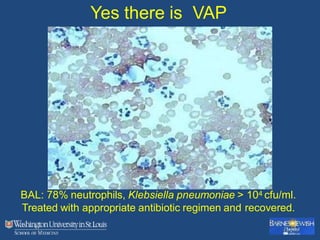

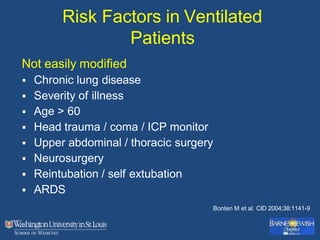

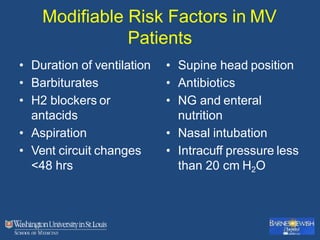

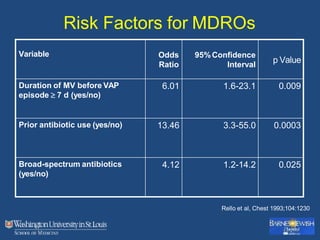

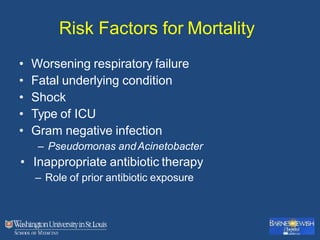

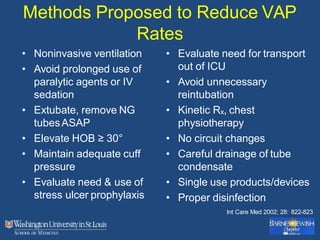

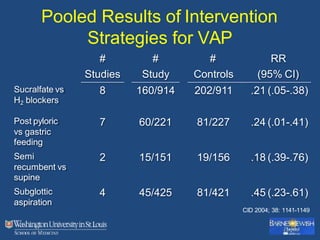

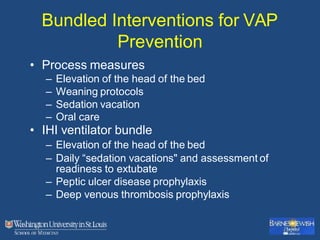

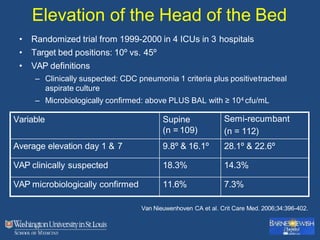

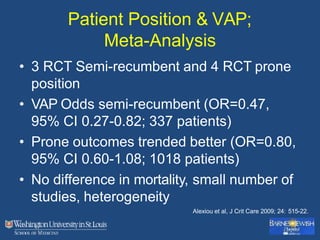

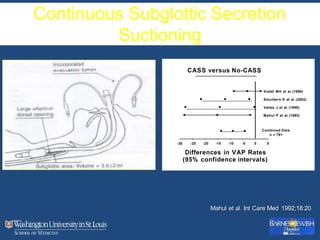

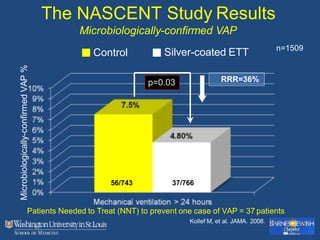

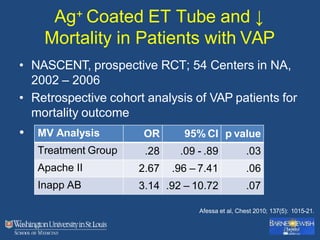

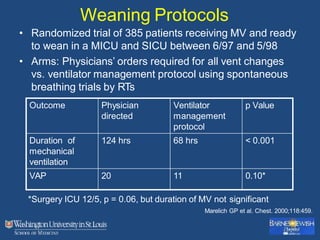

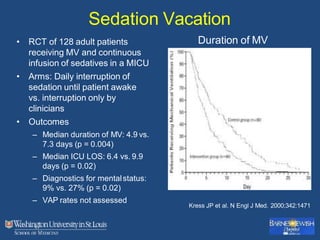

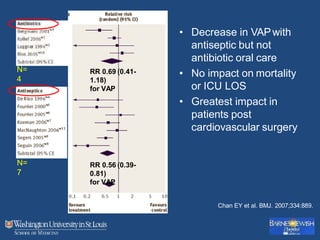

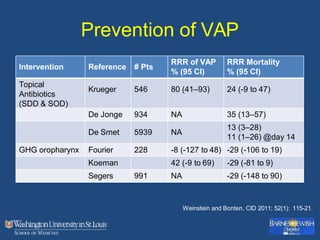

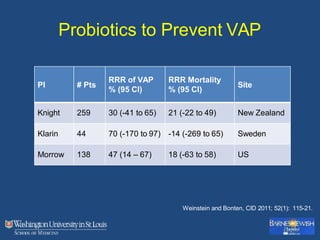

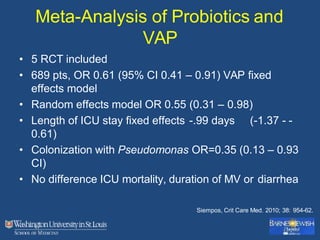

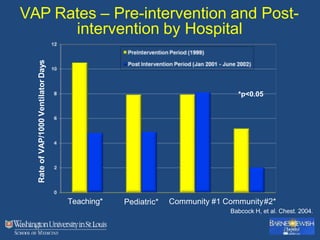

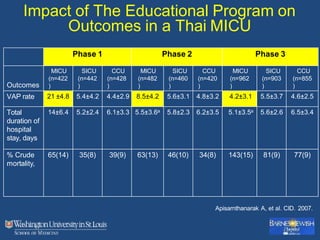

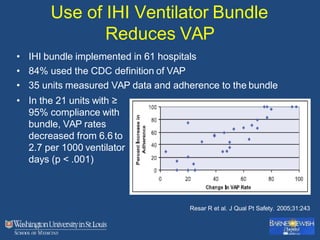

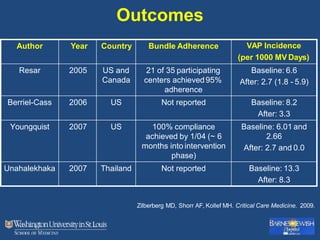

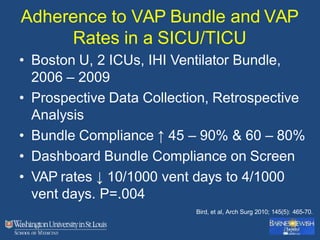

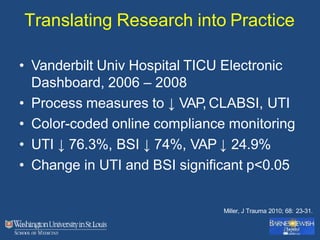

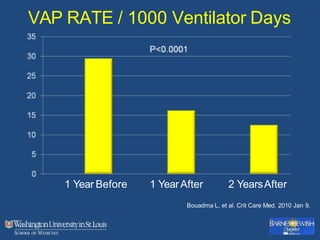

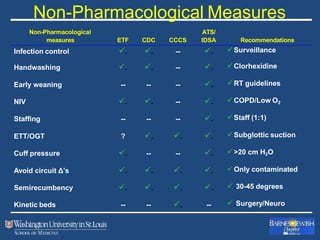

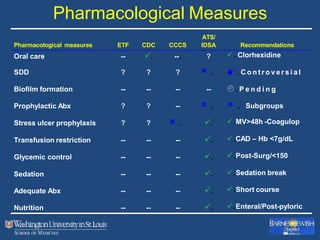

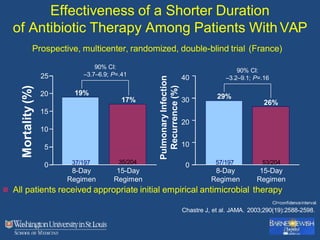

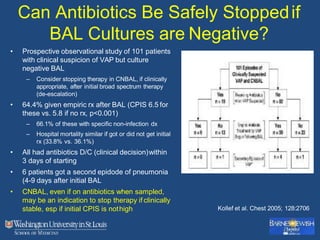

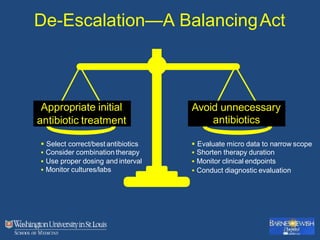

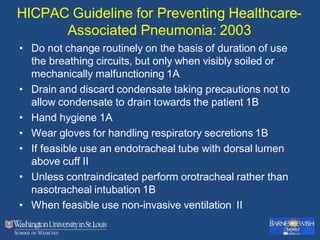

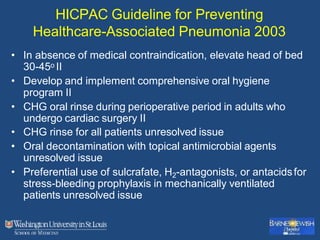

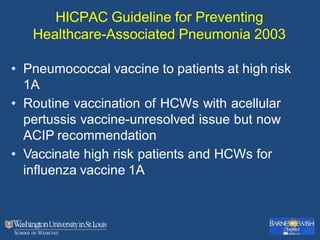

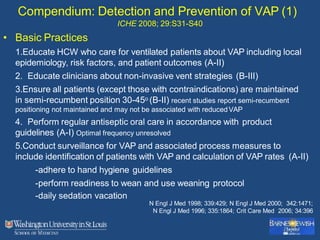

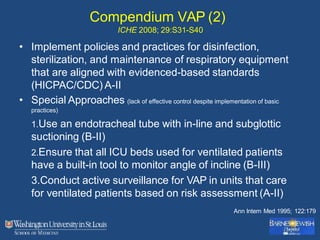

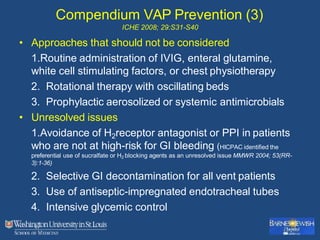

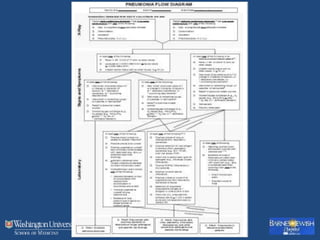

This document discusses ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). It begins with the epidemiology of VAP, including that it is the second most common ICU infection and responsible for half of all ICU antibiotics. Risk factors for VAP include increased duration of mechanical ventilation and prior antibiotic use. Diagnosing VAP is challenging due to the lack of a definitive test. Methods for prevention include keeping the head of the bed elevated, daily sedation vacations, and the use of bundled interventions. Quantitative cultures and invasive diagnostic tests provide more specific diagnosis but do not consistently alter management or improve outcomes.