1) Animals evolve preferences for certain habitats over others because reproductive success is often higher in some habitats than others.

2) Habitat selection is illustrated by European great tits preferring woodlands over hedgerows for nesting. Individuals that can acquire preferred habitats tend to leave more descendants.

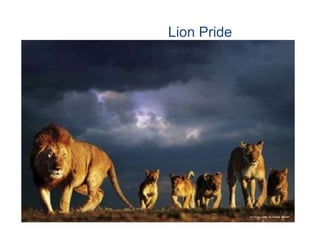

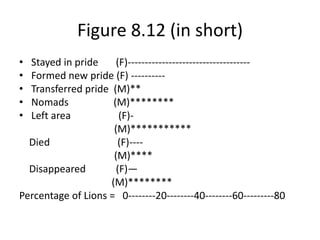

3) Male mammals generally disperse farther than females to avoid inbreeding and competition with other males for mates. Dispersal distances in species like Belding's ground squirrels and behaviors in species like lions also reflect efforts to avoid inbreeding.