1) The document proposes an integrated model for performance management of manufacturing units that combines performance measurement and improvement.

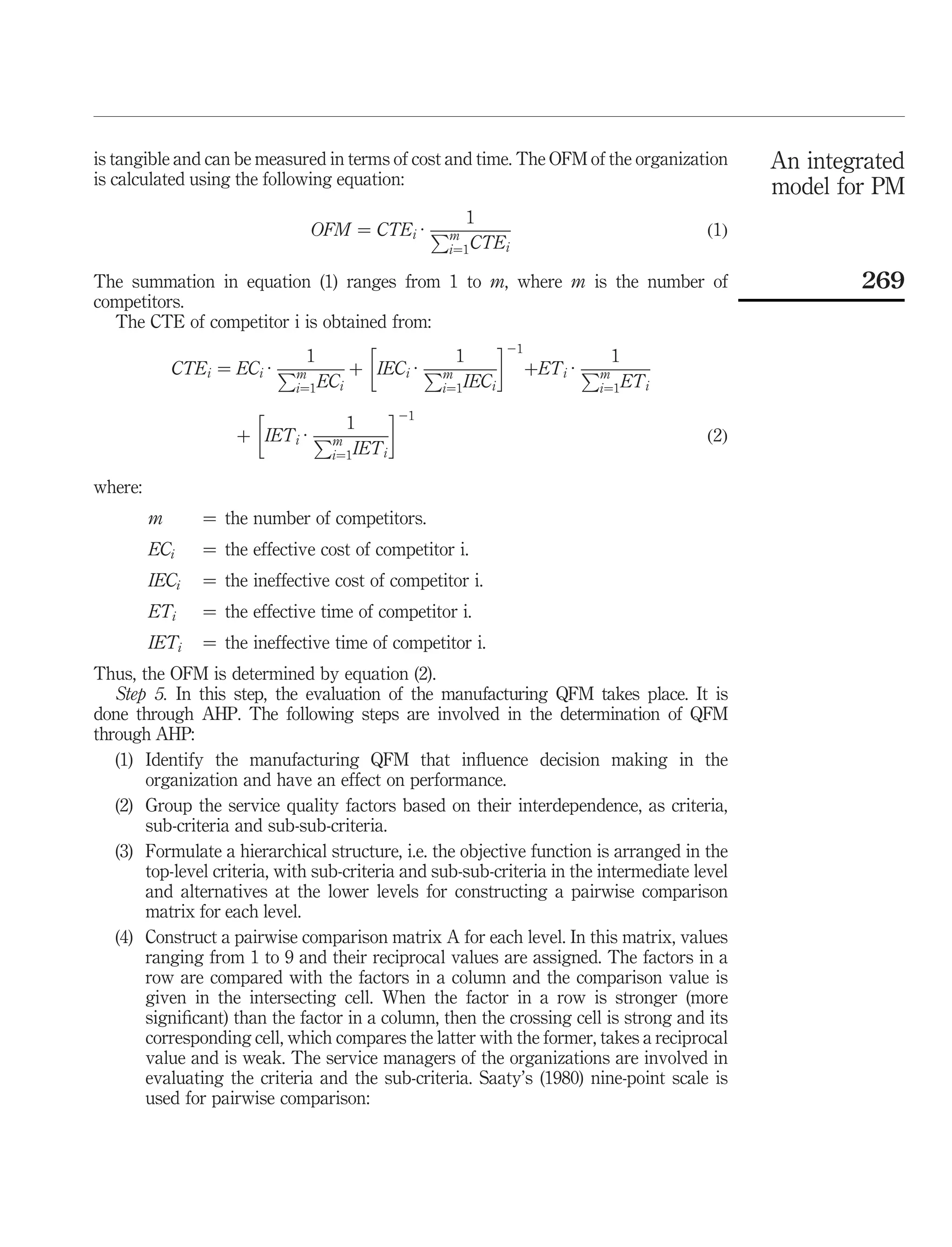

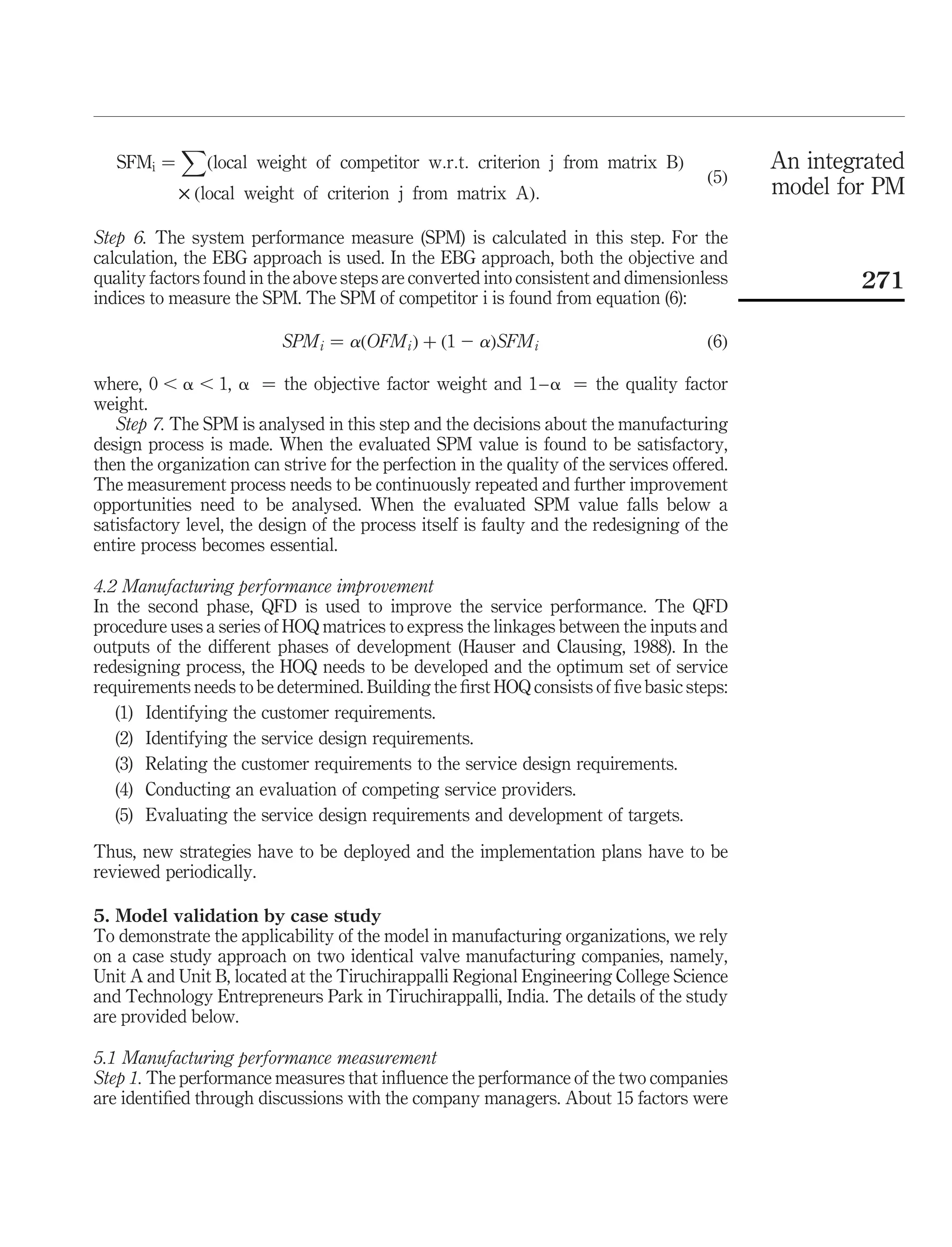

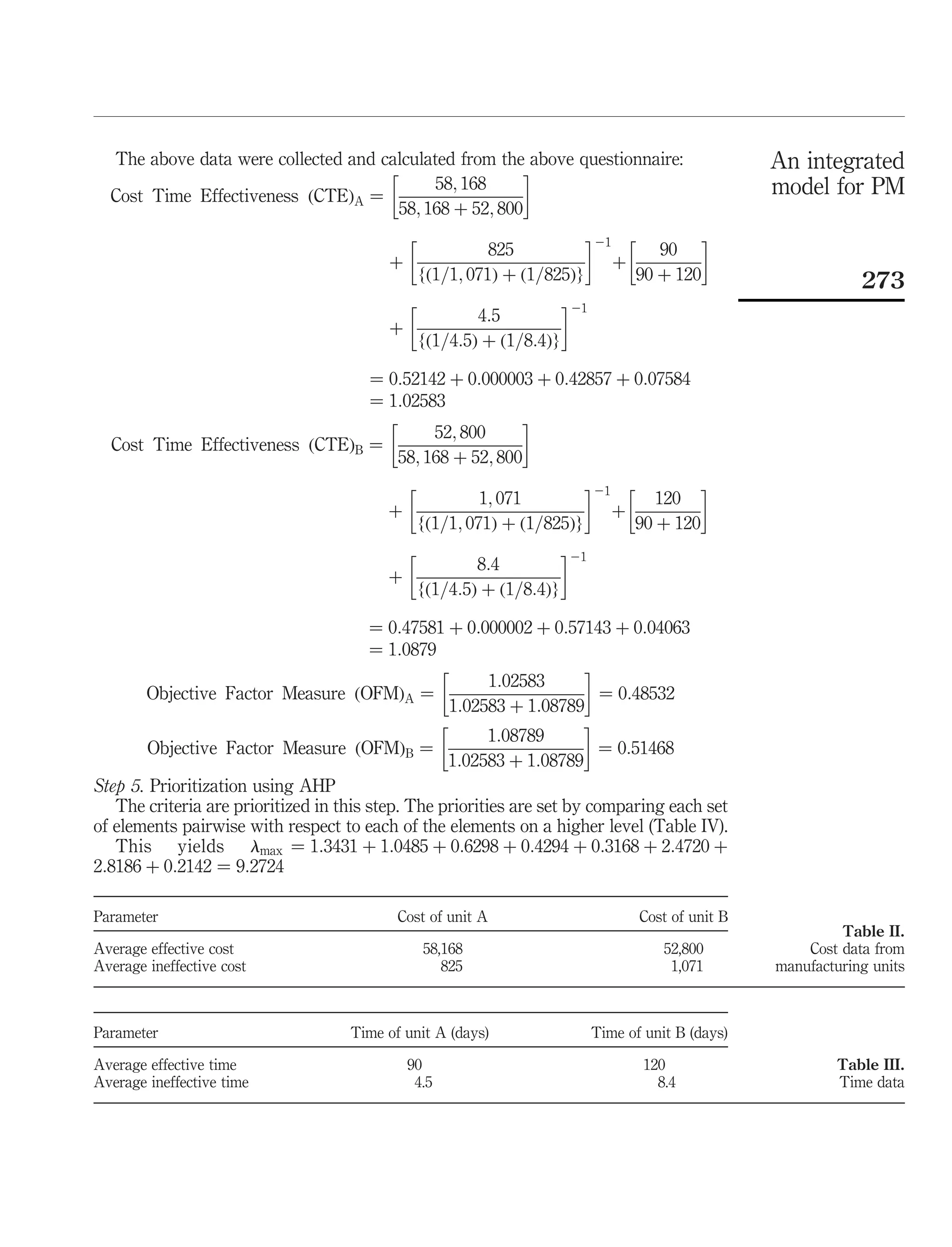

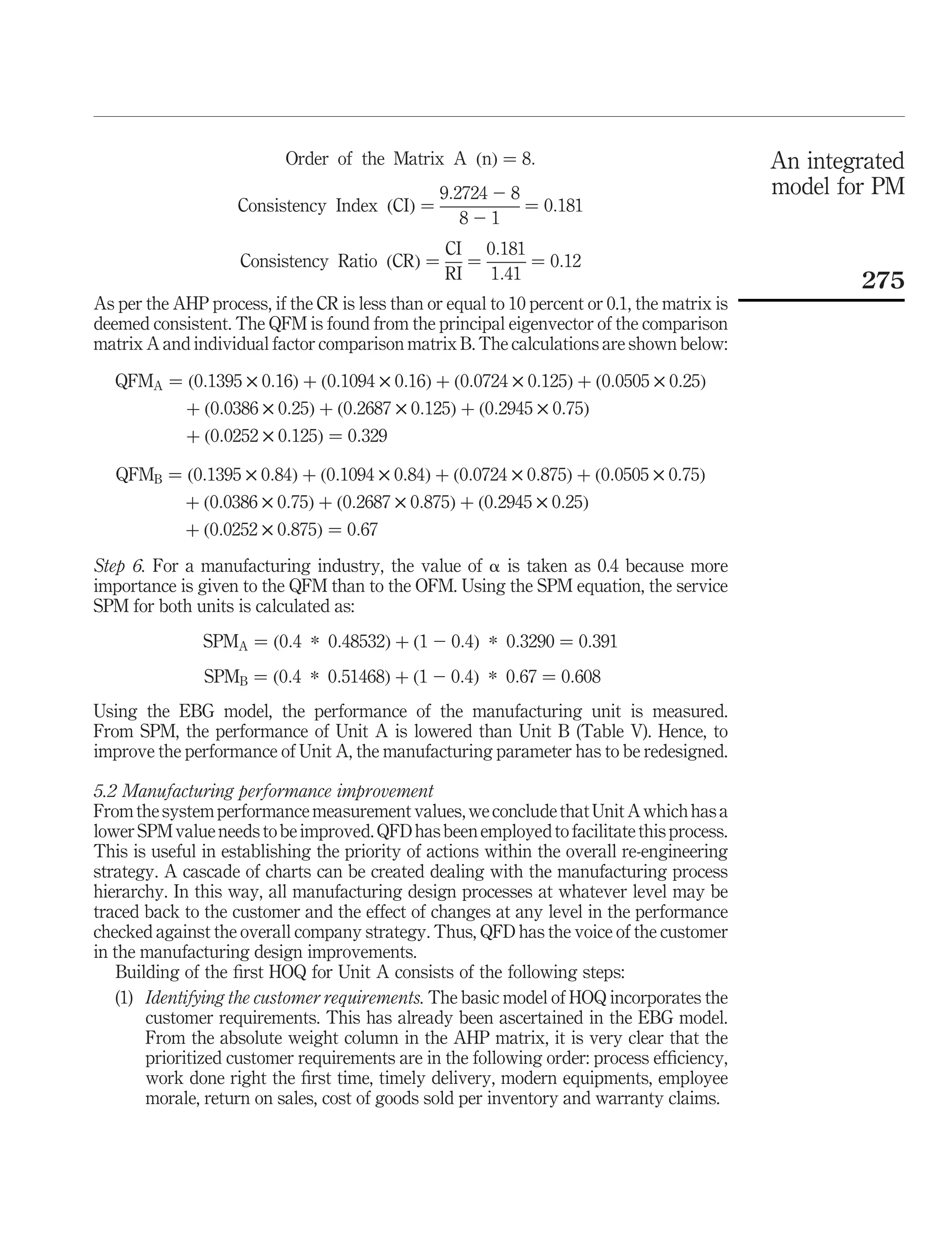

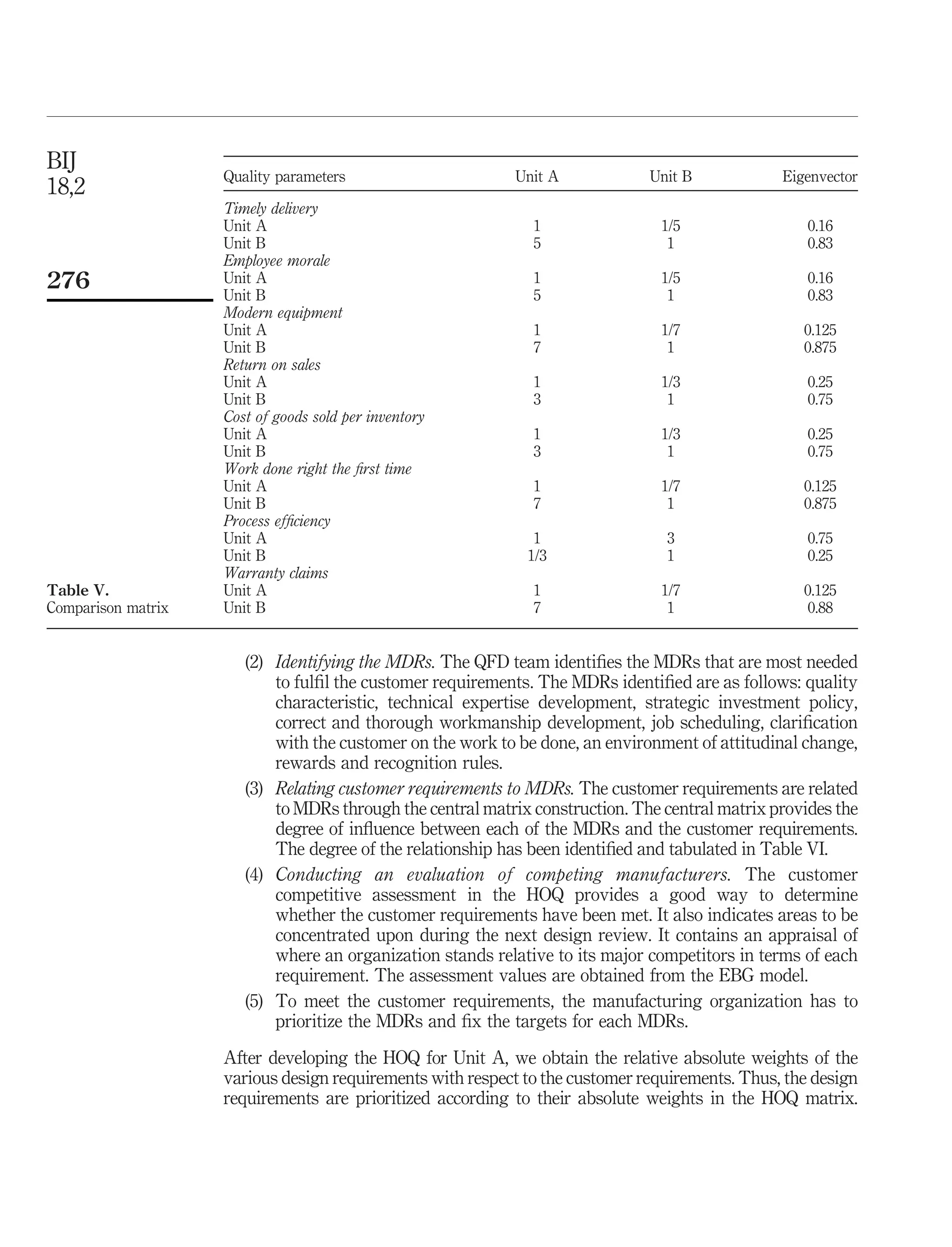

2) Performance is measured using an extended Brown-Gibson model considering objective and service quality factors evaluated through analytic hierarchy process.

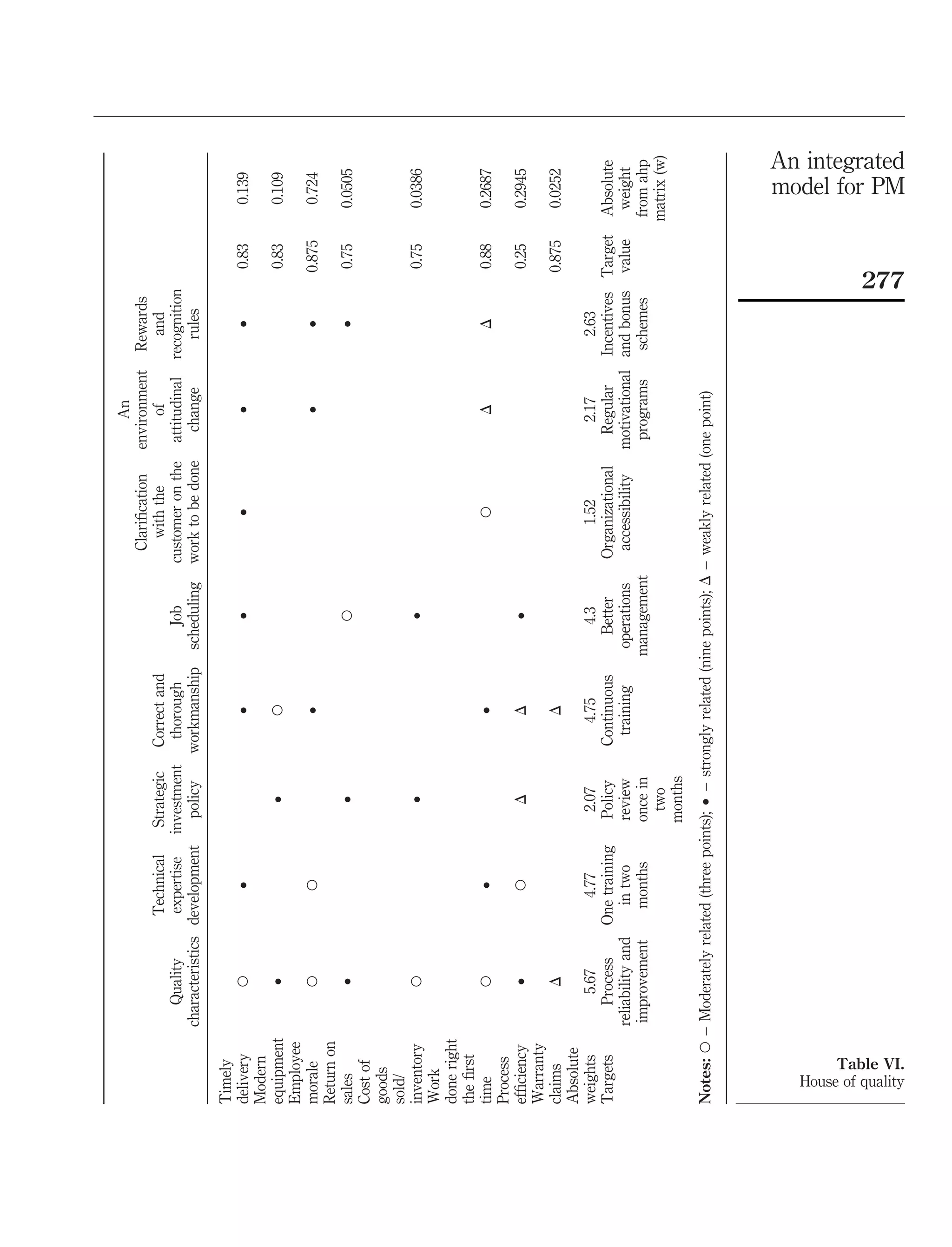

3) If performance measures do not meet satisfactory levels, quality function deployment is used to redesign manufacturing processes.