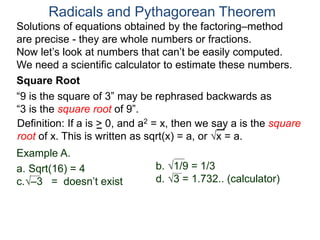

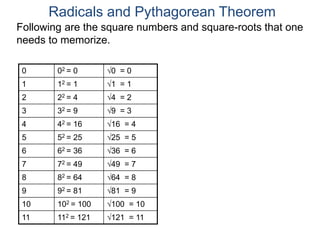

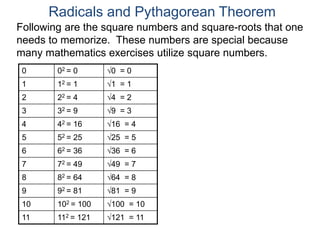

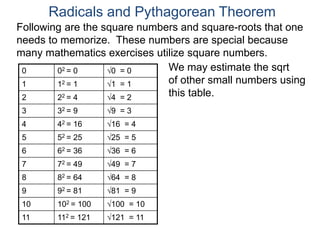

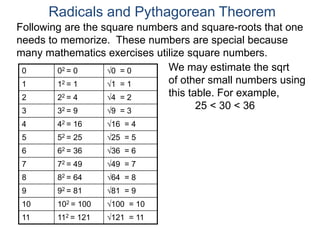

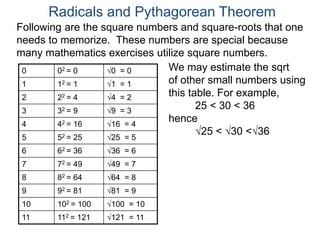

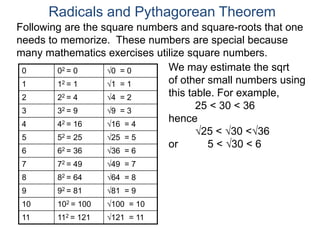

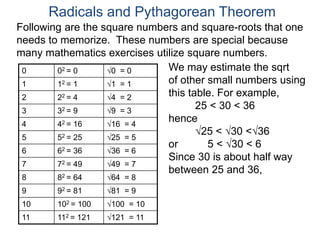

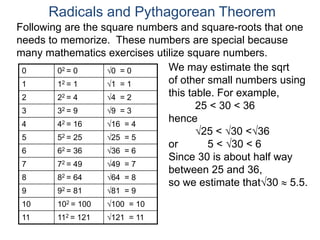

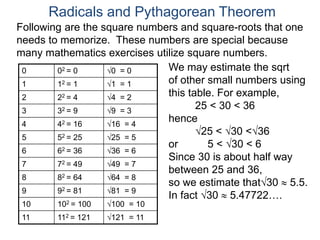

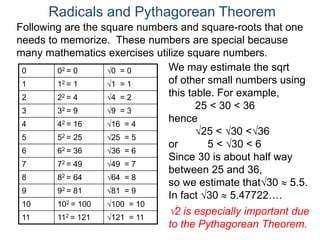

The document discusses square roots and how to estimate them. It provides a table of perfect square numbers from 0 to 121 along with their square roots. It explains that this table can be used to estimate the square roots of other small numbers. For example, since 25 is less than 30 which is less than 36, the square root of 30 must be between 5 and 6. Given that 30 is halfway between 25 and 36, the square root of 30 can be estimated as 5.5.

![Example C. Evaluate 2x3 – 5x2 + 2x

for x = -2, -1, 3 by factoring it first.

2x3 – 5x2 + 2x = x(2x2 – 5x + 2)

= x(2x – 1)(x – 2)

For x = -2:

(-2)[2(-2) – 1] [(-2) – 2] = -2 [-5] [-4] = -40

For x = -1:

(-1)[2(-1) – 1] [(-1) – 2] = -1 [-3] [-3] = -9

For x = 3:

3 [2(3) – 1] [(3) – 2] = 3 [5] [1] = 15

Applications of Factoring

Your turn: Double check these answers via the expanded form.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4radicalsandpythagoreantheorem-x-200316194238/85/4-radicals-and-pythagorean-theorem-x-97-320.jpg)