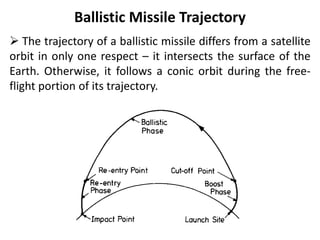

A ballistic missile follows a sub-orbital trajectory and can deliver warheads to a target, relying on the principles of orbital mechanics. The missile's flight path consists of powered, free-flight, and re-entry phases, with its design categorized into various types based on range. Factors such as launch errors can significantly affect a missile's accuracy and impact point, highlighting the complexities of its trajectory calculation.