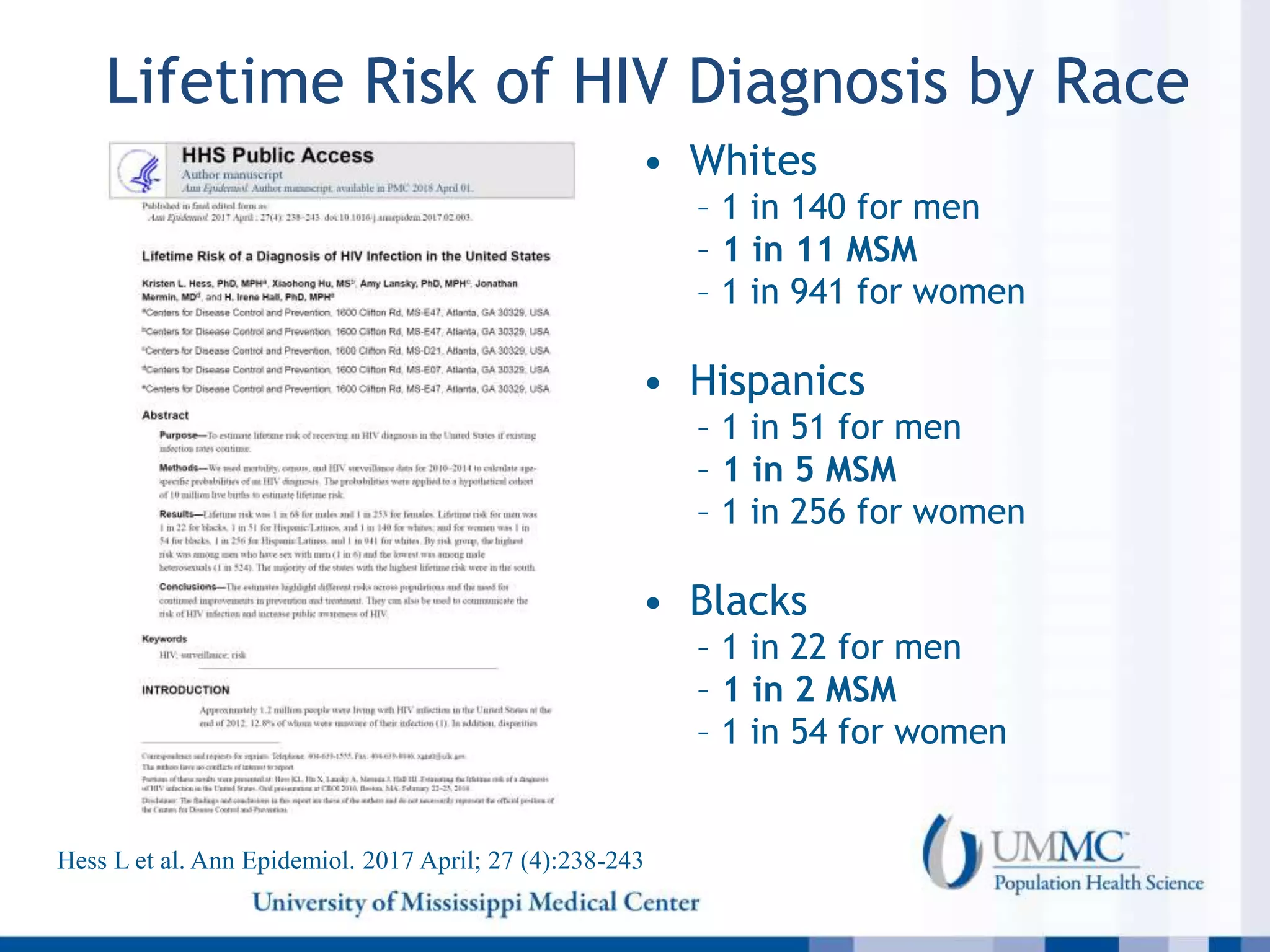

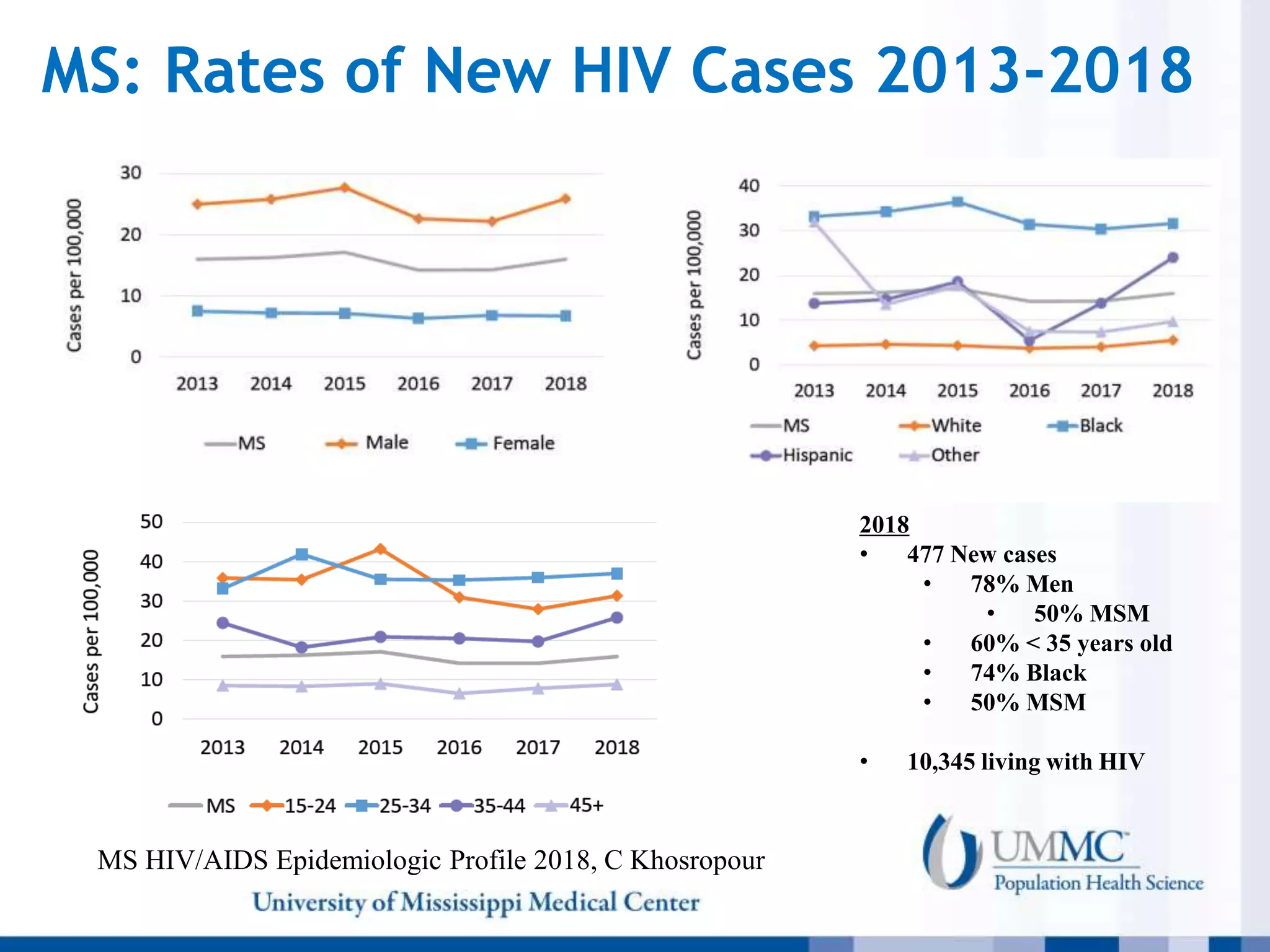

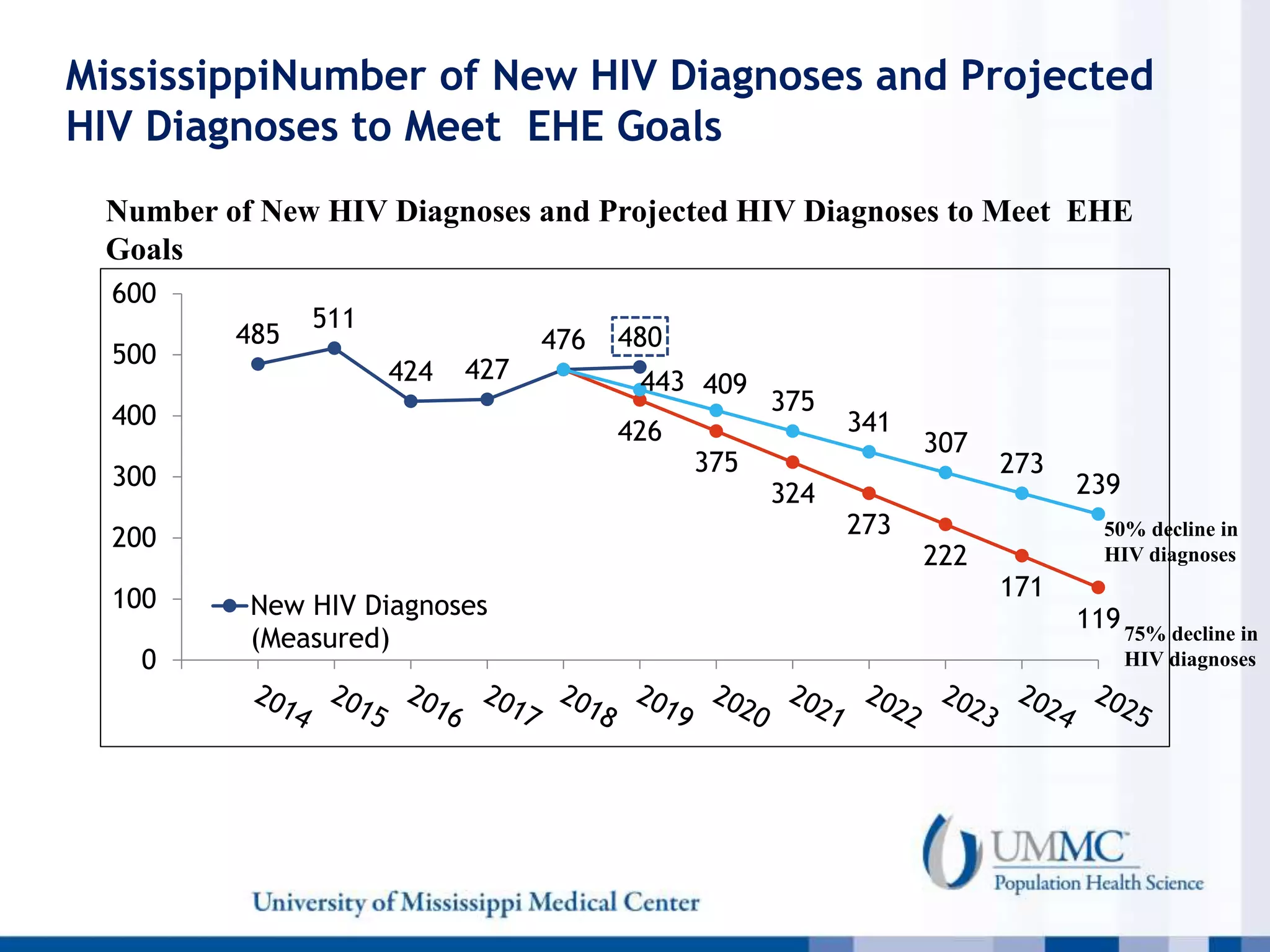

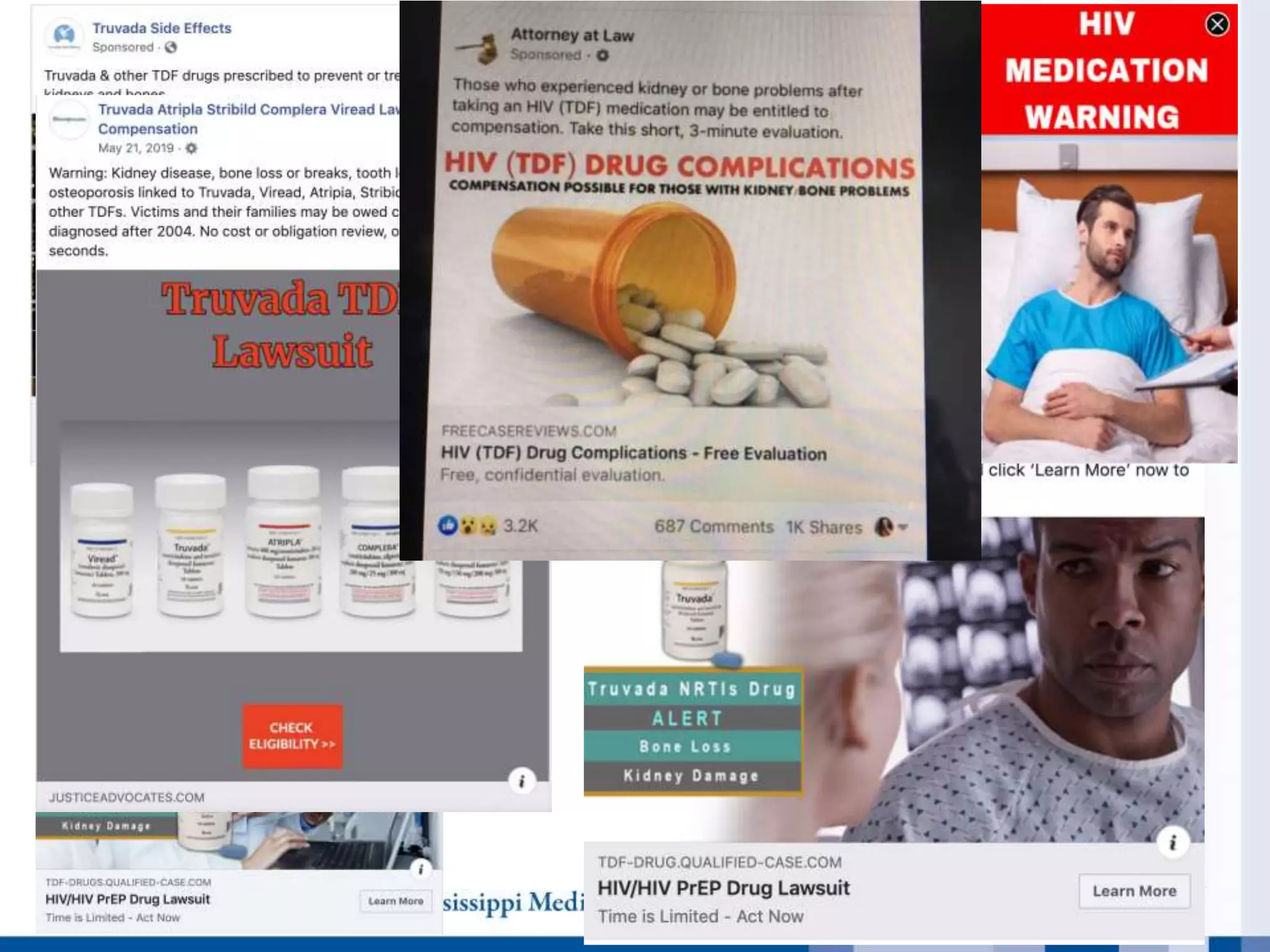

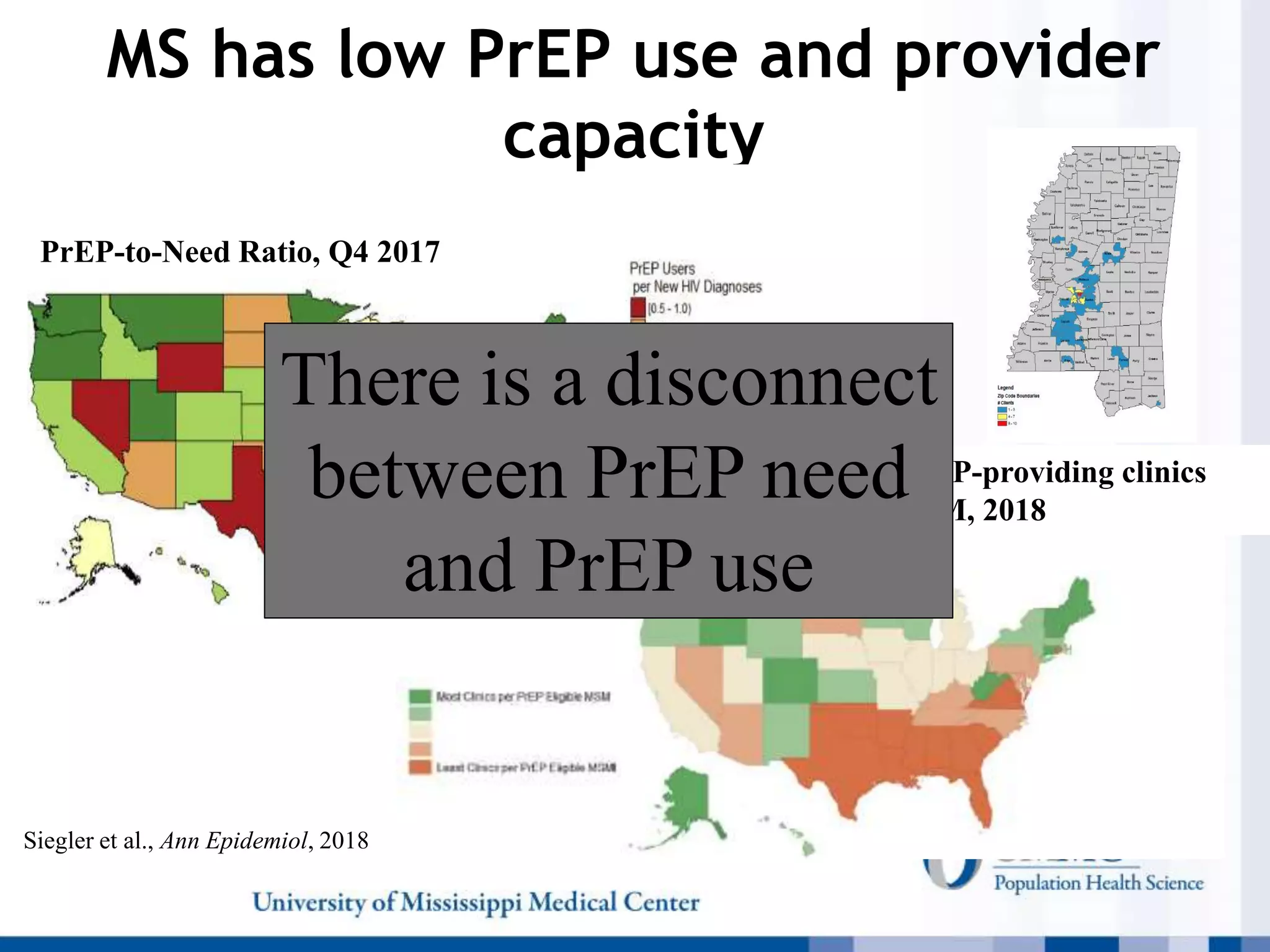

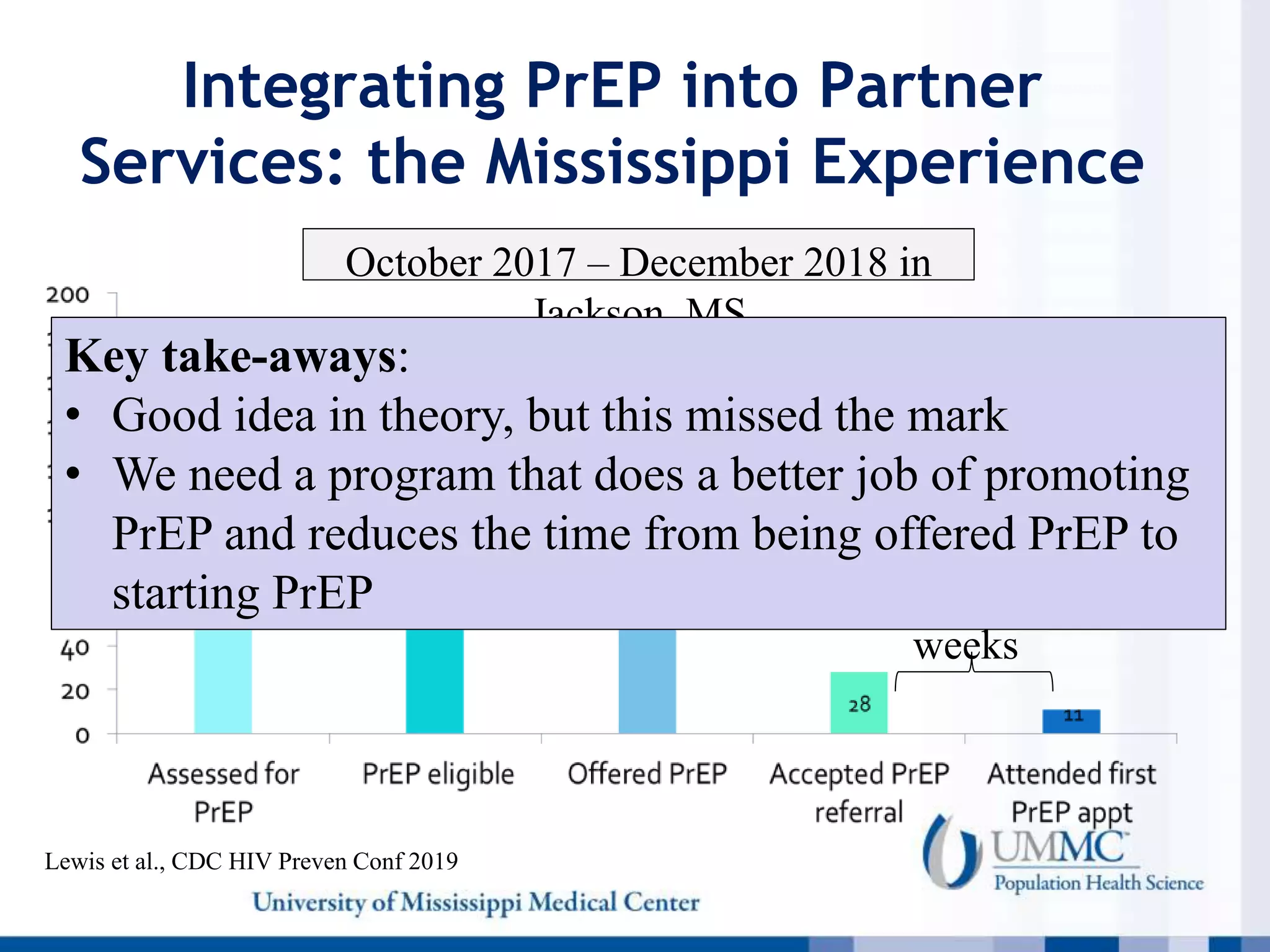

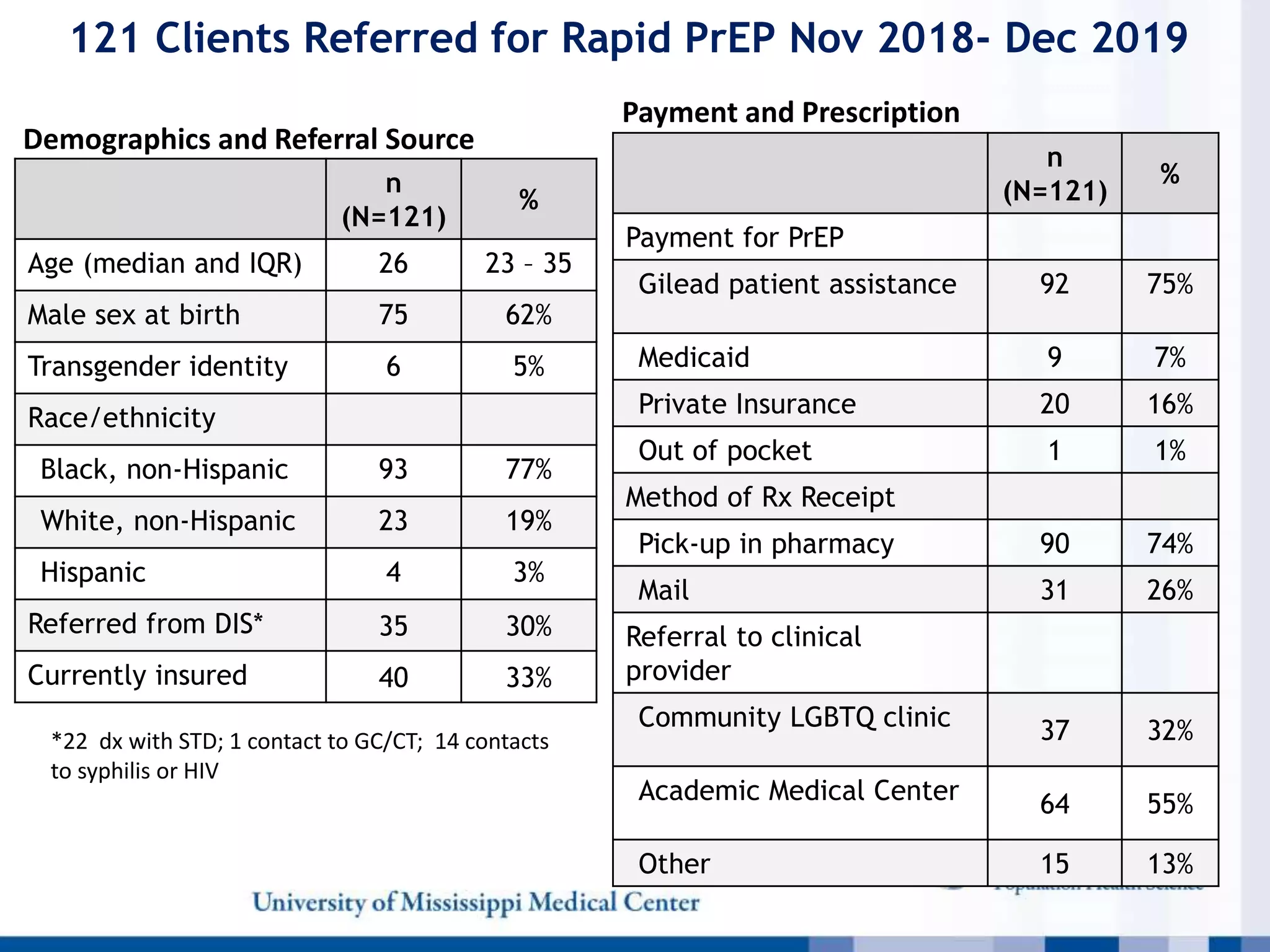

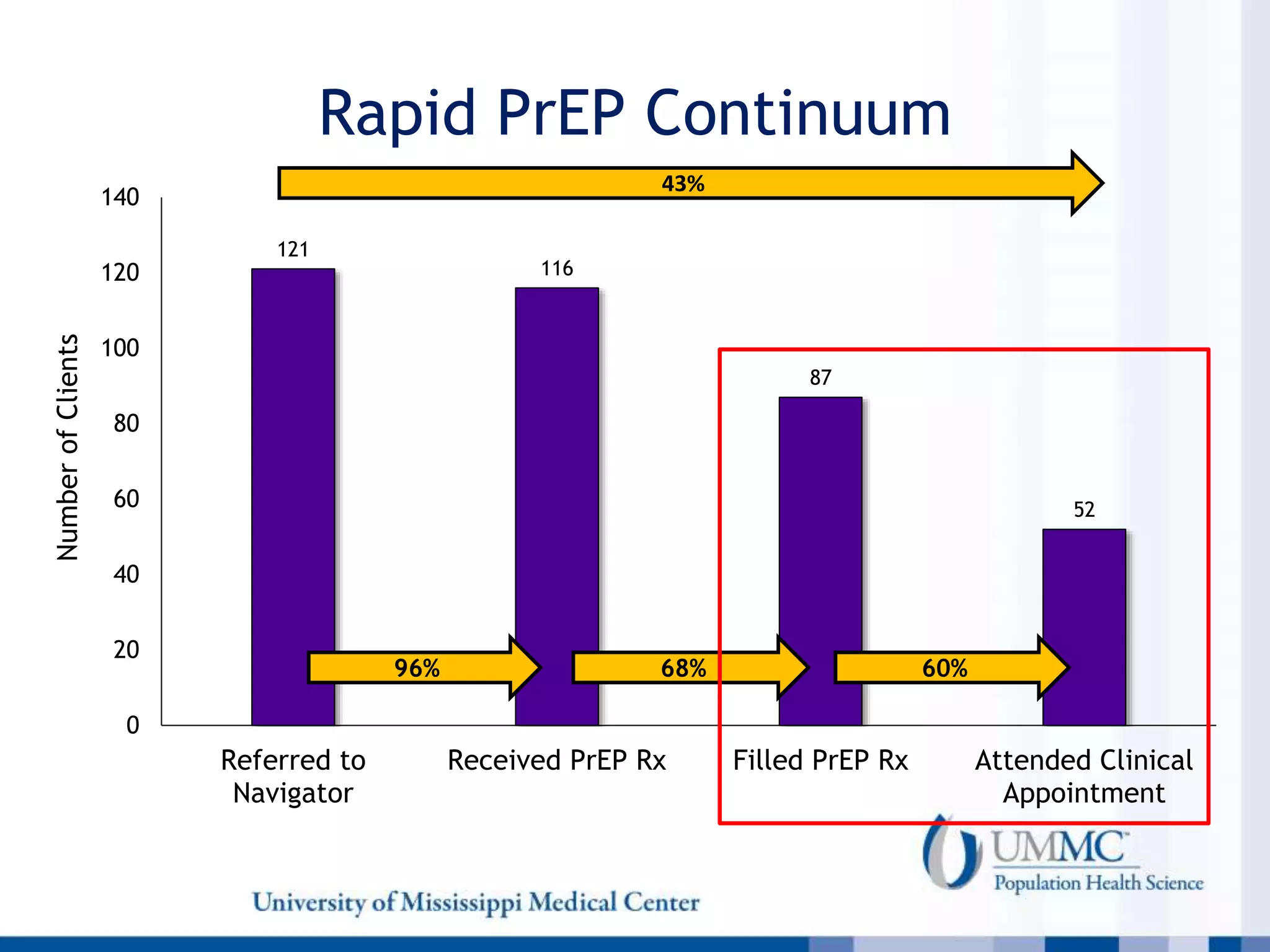

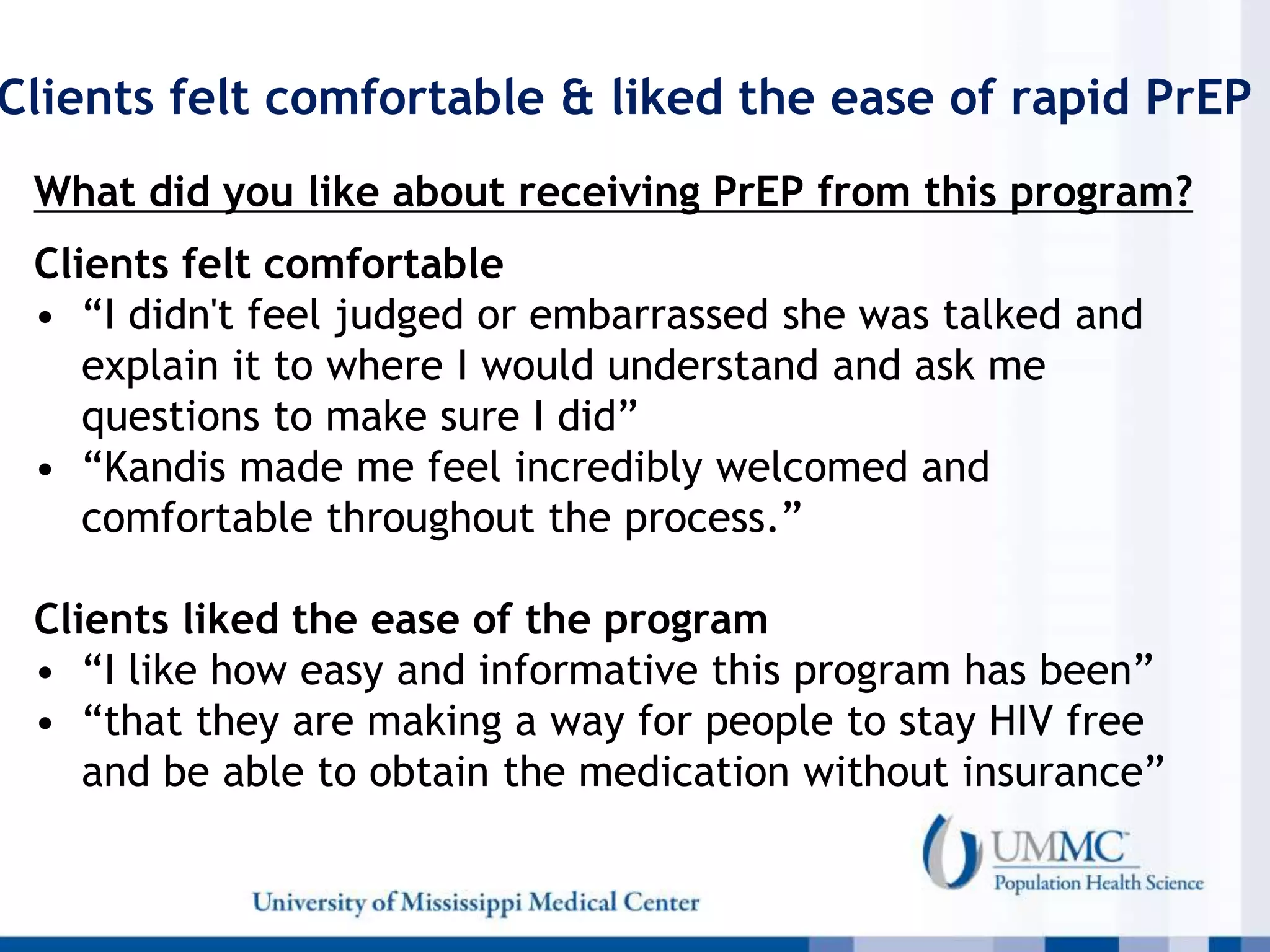

The document outlines a presentation on the HIV epidemic in the U.S., particularly in Mississippi, emphasizing disparities in diagnosis rates, the challenges of implementing PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis), and novel strategies for increasing its uptake among high-risk populations. It highlights the prevalence of HIV in the South, factors affecting PrEP access, and a pilot study that shows a rapid PrEP initiation model's effectiveness. The findings indicate a need for improved education, stigma reduction, and better healthcare access to enhance PrEP implementation in underserved areas.