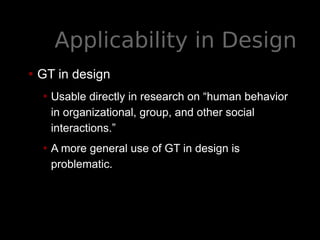

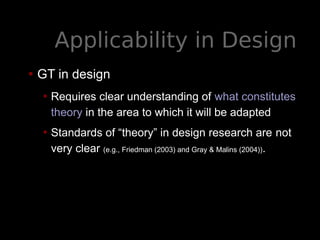

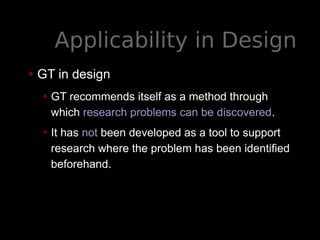

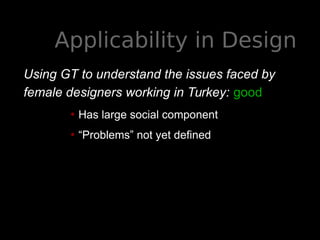

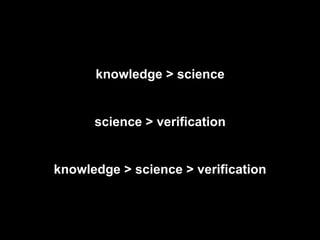

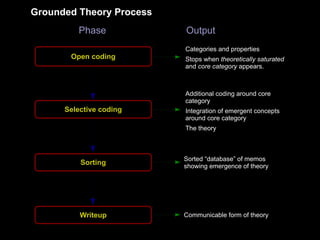

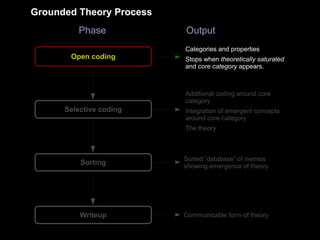

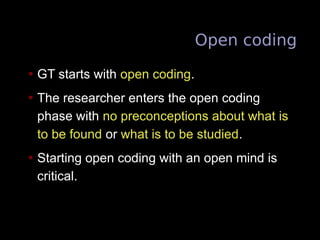

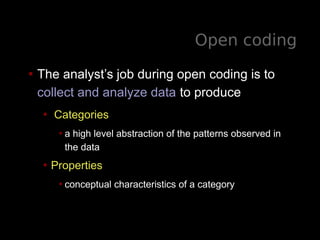

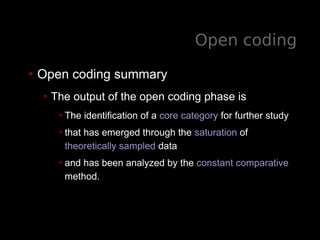

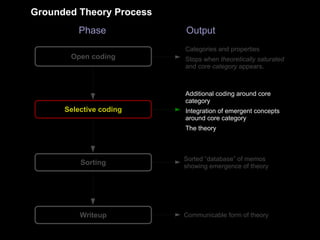

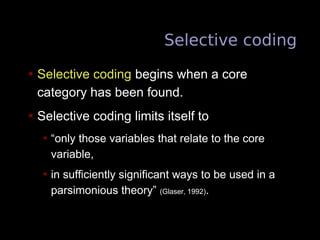

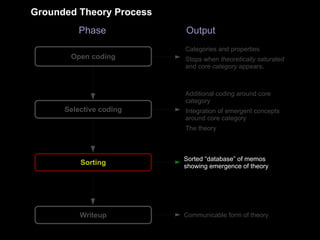

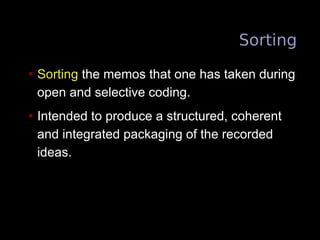

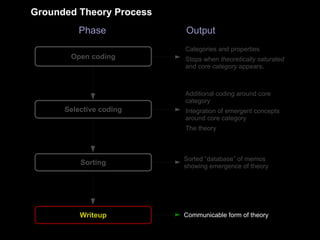

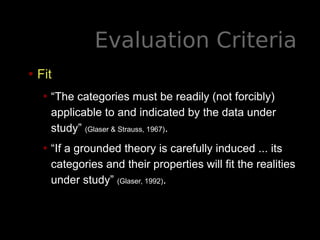

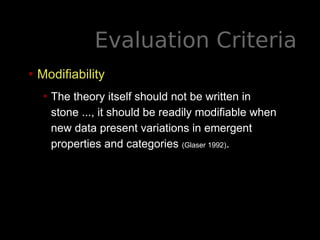

This document provides an overview of grounded theory as a qualitative research methodology. It discusses key concepts of grounded theory including that it is used for theory generation rather than verification, relies on induction rather than deduction, and aims to systematically discover theory from data as concepts emerge. The document reviews grounded theory processes such as open coding, selective coding, sorting memos, and writing up findings. It also discusses criteria for evaluating grounded theories and the potential applicability of grounded theory for design research problems that have a significant social dimension.

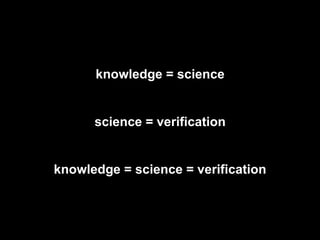

![Generation vs.

verification

• Grounded theory is “the systematic discovery

of theory from data as the concepts emerge

and integrate.”

• “[GT's] yield is just hypotheses!”

• “Testing or verificational work ... is left to

others interested in these types of research

endeavor.” (Glaser, 1992)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/groundedtheoryanddesign-130821171419-phpapp01/85/Grounded-Theory-and-Design-23-320.jpg)

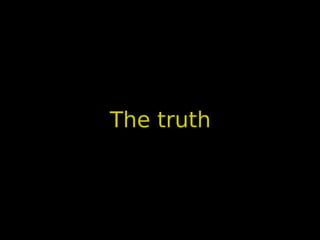

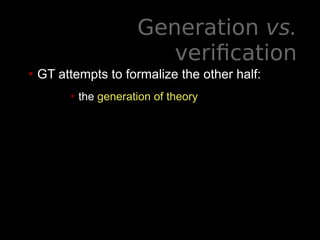

![Generation vs.

verification

• GT was a particular response to a particular

need in a particular context

• “Big man” theories in the 1960s and 1970s.

• “Until [researchers] proceed with a bit more

method their theories will tend to end up

thin, unclear in purpose, and not well

integrated” (Glaser & Strauss, 1967).

• However, the issue of theory generation vs.

verification is universal.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/groundedtheoryanddesign-130821171419-phpapp01/85/Grounded-Theory-and-Design-24-320.jpg)

![Evaluation Criteria

• Work

• “[The theory] must be meaningfully relevant to

and be able to explain the behavior under study”

(Glaser & Strauss, 1967).

• “If a grounded theory works it will explain the

major variations in behavior ... with respect to

the processing of the main concerns of the

subjects (Glaser, 1992).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/groundedtheoryanddesign-130821171419-phpapp01/85/Grounded-Theory-and-Design-57-320.jpg)

![Evaluation Criteria

• Verifiability is not a criterion!

• However:

• “The theory should provide clear enough

categories and hypotheses so that crucial ones

can be verified in present and future research;

• they must be clear enough to be readily

operationalized in quantitative studies when

these studies are appropriate” [emphasis added] (Glaser &

Strauss, 1967).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/groundedtheoryanddesign-130821171419-phpapp01/85/Grounded-Theory-and-Design-60-320.jpg)

![Evaluation Criteria

• Furthermore:

• If and when verification fails or new data become

available through other means, “[a] theory is

neither verified nor thrown out, it is modified to

accommodate by integration the new concepts”

(Glaser, 1992).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/groundedtheoryanddesign-130821171419-phpapp01/85/Grounded-Theory-and-Design-61-320.jpg)

![Applicability in Design

• GT's domain:

• “Grounded theory methods are not bound by

either discipline or data collection … its methods

work quite well for analyzing data within the

perspective of any discipline [and] it is a useful

methodology for multidisciplinary studies”

[emphasis original] (Glaser, 1992).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/groundedtheoryanddesign-130821171419-phpapp01/85/Grounded-Theory-and-Design-64-320.jpg)