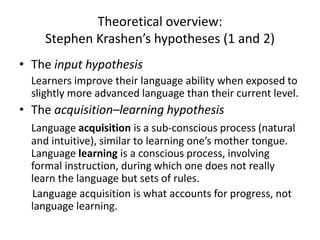

This document discusses Stephen Krashen's hypotheses for language acquisition and provides guidance for teaching listening and speaking based on these hypotheses. The key points are:

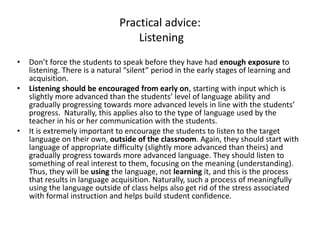

1) According to Krashen, language is acquired through comprehensible input rather than formal instruction, and acquisition, not learning, leads to improved ability.

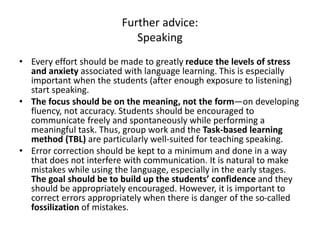

2) For listening and speaking, students should be exposed to comprehensible input before producing speech, and errors should be minimized to build confidence.

3) Teachers should focus on meaning over form, encourage fluency through tasks and group work, and correct errors later to prevent fossilization. Flexibility is needed to meet different student needs.