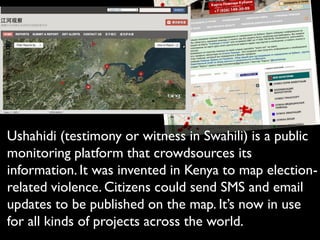

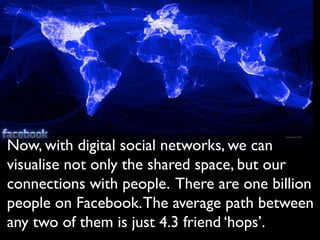

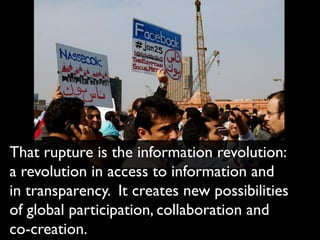

The document discusses reimagining global democracy in the digital age. It argues that globalization has posed challenges for democracy which is traditionally confined to the nation-state. A world parliament may not be effective or legitimate. Instead, digital democracy through open global deliberation and participation on the internet can realize a decentralized and networked form of global governance. The internet creates possibilities for free discussion, participation in political processes, and a global political community. Examples of digital collaboration like ProMED-mail and deforestation monitoring networks show how this can work in practice to address global issues.

![1945

‘We the peoples of the United Nations...’

[not nations]

Preamble to the United Nations Charter](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/globaldigitaldemocracy-130306081933-phpapp01/85/Global-digital-democracy-15-320.jpg)

![“designing effective and

legitimate institutions is [the]

crucial problem of political

design for the twenty-first

century”

Joe Nye and Bob Keohane

Professors at Harvard and Princeton](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/globaldigitaldemocracy-130306081933-phpapp01/85/Global-digital-democracy-27-320.jpg)

![The project was created by Imazon, a Brazilian

NGO, now supported by Google. As Google’s lead

mapper said: “a collaborative monitoring

community, powered by the internet, [has] never

been possible before.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/globaldigitaldemocracy-130306081933-phpapp01/85/Global-digital-democracy-67-320.jpg)