The document discusses the use of neural networks for communication among multi-agents, exploring two forms of communication: discrete and continuous, aimed at shared learning and coordinated actions. It covers concepts such as reinforcement learning and the architecture of graph neural networks, emphasizing their application in controlling agent cooperation and maximizing expected rewards in decentralized environments. The analysis includes mechanisms for interpreting symbols and actions within the learning process, illustrating the complexities involved in agent communication and collaboration.

![Examples

● Communication of continuous vectors

(In other words, multi-agents can be seen just one NN)

● Merge and return total information

● Each agent outputs an action a

● Learning by REINFORCE; reward*log(p(a))

5

Connecting Neural Models

Anonymous Author(s)

Affiliation

Address

email

Abstract

ke two contributions. First, we simplify and extend the graph neural network

cond, we show how this architecture can be used to control groups of cooperating

f the model consists of multilayer neural networks fi

that take as input vectors

a vector hi+1

. The model takes as input a set of vectors {h0

1, h0

2, ..., h0

m}, and

hi+1

j = fi

(hi

j, ci

j)

ci+1

j =

X

j06=j

hi+1

j0 ;

onnecting Neural Models

Anonymous Author(s)

Affiliation

Address

email

Abstract

ontributions. First, we simplify and extend the graph neural network

show how this architecture can be used to control groups of cooperating

el consists of multilayer neural networks fi

that take as input vectors

hi+1

. The model takes as input a set of vectors {h0

1, h0

2, ..., h0

m}, and

hi+1

j = fi

(hi

j, ci

j)

ci+1

j =

X

j06=j

hi+1

j0 ;

Anonymous Author(s)

Affiliation

Address

email

Abstract

bstract

oduction

rk we make two contributions. First, we simplify and extend the graph neural network

re of ??. Second, we show how this architecture can be used to control groups of cooperating

del

est form of the model consists of multilayer neural networks fi

that take as input vectors

and output a vector hi+1

. The model takes as input a set of vectors {h0

1, h0

2, ..., h0

m}, and

hi+1

j = fi

(hi

j, ci

j)

ci+1

j =

X

j06=j

hi+1

j0 ;

= 0 for all j, and i 2 {0, .., K} (we will call K the number of hops in the network).

, we can take the final hK

j and output them directly, so that the model outputs a vector

ding to each input vector, or we can feed them into another network to get a single vector or

put.

is a simple linear layer followed by a nonlinearity :

i+1 i i i i

mean

contribution. In this setting, there is no difference between each agent having its own c36

viewing them as pieces of a larger model controlling all agents. Taking the latter pers37

controller is a large feed-forward neural network that maps inputs for all agents to their a38

agent occupying a subset of units. A specific connectivity structure between layers (a) ins39

broadcast communication channel between agents and (b) propagates the agent state in th40

an RNN.41

Because the agents will receive reward, but not necessarily supervision for each action, re42

learning is used to maximize expected future reward. We explore two forms of communic43

the controller: (i) discrete and (ii) continuous. In the former case, communication is an44

will be treated as such by the reinforcement learning. In the continuous case, the sig45

between agents are no different than hidden states in a neural network; thus credit assign46

communication can be performed using standard backpropagation (within the outer RL47

We use policy gradient [33] with a state specific baseline for delivering a gradient to48

Denote the states in an episode by s(1), ..., s(T), and the actions taken at each of49

as a(1), ..., a(T), where T is the length of the episode. The baseline is a scalar fun50

states b(s, ✓), computed via an extra head on the model producing the action probabili51

maximizing the expected reward with policy gradient, the models are also trained to m52

distance between the baseline value and actual reward. Thus, after finishing an episode53

the model parameters ✓ by54

✓ =

TX

t=1

log p(a(t)|s(t), ✓)

✓

TX

i=t

r(i) b(s(t), ✓)

✓

TX

i=t

r(i) b(s(t)

Here r(t) is reward given at time t, and the hyperparameter is for balancing the rew55

baseline objectives, set to 0.03 in all experiments.56

3 Model57

We now describe the model used to compute p(a(t)|s(t), ✓) at a given time t (ommiti58

index for brevity). Let sj be the jth agent’s view of the state of the environment. The59

controller is the concatenation of all state-views s = {s1, ..., sJ }, and the controller i60

a = (s), where the output a is a concatenation of discrete actions a = {a1, ..., aJ } for61

Note that this single controller encompasses the individual controllers for each agent62

the communication between agents.63

learning is used to maximize expected future reward. We explore two forms of communication within43

the controller: (i) discrete and (ii) continuous. In the former case, communication is an action, and44

will be treated as such by the reinforcement learning. In the continuous case, the signals passed45

between agents are no different than hidden states in a neural network; thus credit assignment for the46

communication can be performed using standard backpropagation (within the outer RL loop).47

We use policy gradient [33] with a state specific baseline for delivering a gradient to the model.48

Denote the states in an episode by s(1), ..., s(T), and the actions taken at each of those states49

as a(1), ..., a(T), where T is the length of the episode. The baseline is a scalar function of the50

states b(s, ✓), computed via an extra head on the model producing the action probabilities. Beside51

maximizing the expected reward with policy gradient, the models are also trained to minimize the52

distance between the baseline value and actual reward. Thus, after finishing an episode, we update53

the model parameters ✓ by54

✓ =

TX

t=1

log p(a(t)|s(t), ✓)

✓

TX

i=t

r(i) b(s(t), ✓)

✓

TX

i=t

r(i) b(s(t), ✓)

2

.

Here r(t) is reward given at time t, and the hyperparameter is for balancing the reward and the55

baseline objectives, set to 0.03 in all experiments.56

3 Model57

We now describe the model used to compute p(a(t)|s(t), ✓) at a given time t (ommiting the time58

index for brevity). Let sj be the jth agent’s view of the state of the environment. The input to the59

controller is the concatenation of all state-views s = {s1, ..., sJ }, and the controller is a mapping60

a = (s), where the output a is a concatenation of discrete actions a = {a1, ..., aJ } for each agent.61

Note that this single controller encompasses the individual controllers for each agents, as well as62

the communication between agents.63

One obvious choice for is a fully-connected multi-layer neural network, which could extract64

features h from s and use them to predict good actions with our RL framework. This model would65

allow agents to communicate with each other and share views of the environment. However, it66

is inflexible with respect to the composition and number of agents it controls; cannot deal well67

with agents joining and leaving the group and even the order of the agents must be fixed. On the68

other hand, if no communication is used then we can write a = { (s1), ..., (sJ )}, where is a69

per-agent controller applied independently. This communication-free model satisfies the flexibility70

requirements1

, but is not able to coordinate their actions.71

, and computes:

hi+1

j = fi

(hi

j, ci

j) (1)

ci+1

j =

1

J 1

X

j06=j

hi+1

j0 . (2)

a single linear layer followed by a nonlinearity , we have: hi+1

j = (Hi

hi

j +

can be viewed as a feedforward network with layers hi+1

= (Ti

hi

) where hi

of all hi

j and T takes the block form:

Ti

=

Hi

Ci

Ci

... Ci

Ci

Hi

Ci

... Ci

Ci

Ci

Hi

... Ci

...

...

...

...

...

Ci

Ci

Ci

... Hi

,

eural Models

Author(s)

tion

ess

il

ract

e simplify and extend the graph neural network

cture can be used to control groups of cooperating

ral Models

thor(s)

mplify and extend the graph neural network

odels

extend the graph neural network

g Neural Models

ymous Author(s)

Affiliation

Address

email

Abstract

rst, we simplify and extend the graph neural network

architecture can be used to control groups of cooperating

multilayer neural networks fi

that take as input vectors

0 0 0

2 Problem Formulation33

We consider the setting where we have M agents, all cooperating to maximize reward R in some34

environment. We make the simplifying assumption that each agent receives R, independent of their35

contribution. In this setting, there is no difference between each agent having its own controller, or36

viewing them as pieces of a larger model controlling all agents. Taking the latter perspective, our37

controller is a large feed-forward neural network that maps inputs for all agents to their actions, each38

agent occupying a subset of units. A specific connectivity structure between layers (a) instantiates the39

broadcast communication channel between agents and (b) propagates the agent state in the manner of40

an RNN.41

Because the agents will receive reward, but not necessarily supervision for each action, reinforcement42

learning is used to maximize expected future reward. We explore two forms of communication within43

the controller: (i) discrete and (ii) continuous. In the former case, communication is an action, and44

will be treated as such by the reinforcement learning. In the continuous case, the signals passed45

between agents are no different than hidden states in a neural network; thus credit assignment for the46

communication can be performed using standard backpropagation (within the outer RL loop).47

We use policy gradient [33] with a state specific baseline for delivering a gradient to the model.48

Denote the states in an episode by s(1), ..., s(T), and the actions taken at each of those states49

as a(1), ..., a(T), where T is the length of the episode. The baseline is a scalar function of the50

states b(s, ✓), computed via an extra head on the model producing the action probabilities. Beside51

maximizing the expected reward with policy gradient, the models are also trained to minimize the52

distance between the baseline value and actual reward. Thus, after finishing an episode, we update53

the model parameters ✓ by54

TX log p(a(t)|s(t), ✓)

TX TX

2

Problem Formulation

consider the setting where we have M agents, all cooperating to maximize reward R in some

ironment. We make the simplifying assumption that each agent receives R, independent of their

tribution. In this setting, there is no difference between each agent having its own controller, or

wing them as pieces of a larger model controlling all agents. Taking the latter perspective, our

troller is a large feed-forward neural network that maps inputs for all agents to their actions, each

nt occupying a subset of units. A specific connectivity structure between layers (a) instantiates the

adcast communication channel between agents and (b) propagates the agent state in the manner of

RNN.

ause the agents will receive reward, but not necessarily supervision for each action, reinforcement

ning is used to maximize expected future reward. We explore two forms of communication within

controller: (i) discrete and (ii) continuous. In the former case, communication is an action, and

be treated as such by the reinforcement learning. In the continuous case, the signals passed

ween agents are no different than hidden states in a neural network; thus credit assignment for the

mmunication can be performed using standard backpropagation (within the outer RL loop).

use policy gradient [33] with a state specific baseline for delivering a gradient to the model.

note the states in an episode by s(1), ..., s(T), and the actions taken at each of those states

a(1), ..., a(T), where T is the length of the episode. The baseline is a scalar function of the

es b(s, ✓), computed via an extra head on the model producing the action probabilities. Beside

ximizing the expected reward with policy gradient, the models are also trained to minimize the

ance between the baseline value and actual reward. Thus, after finishing an episode, we update

model parameters ✓ by

✓ =

TX

t=1

log p(a(t)|s(t), ✓)

✓

TX

i=t

r(i) b(s(t), ✓)

✓

TX

i=t

r(i) b(s(t), ✓)

2

.

e r(t) is reward given at time t, and the hyperparameter is for balancing the reward and the

eline objectives, set to 0.03 in all experiments.

Model

, ..., h0

J ], and computes:

hi+1

j = fi

(hi

j, ci

j) (1)

ci+1

j =

1

J 1

X

j06=j

hi+1

j0 . (2)

at fi

is a single linear layer followed by a nonlinearity , we have: hi+1

j = (Hi

hi

j +

e model can be viewed as a feedforward network with layers hi+1

= (Ti

hi

) where hi

enation of all hi

j and T takes the block form:

Ti

=

Hi

Ci

Ci

... Ci

Ci

Hi

Ci

... Ci

Ci

Ci

Hi

... Ci

...

...

...

...

...

Ci

Ci

Ci

... Hi

,

g Neural Models

mous Author(s)

Affiliation

Address

email

Abstract

rst, we simplify and extend the graph neural network

rchitecture can be used to control groups of cooperating

Neural Models

ous Author(s)

filiation

ddress

mail

stract

we simplify and extend the graph neural network

hitecture can be used to control groups of cooperating

al Models

or(s)

lify and extend the graph neural network

an be used to control groups of cooperating

ecting Neural Models

Anonymous Author(s)

Affiliation

Address

email

Abstract

ions. First, we simplify and extend the graph neural network

how this architecture can be used to control groups of cooperating

sists of multilayer neural networks fi

that take as input vectors

The model takes as input a set of vectors {h0

1, h0

2, ..., h0

m}, and

2 Problem Formulation33

We consider the setting where we have M agents, all cooperating to maximize reward R in some34

environment. We make the simplifying assumption that each agent receives R, independent of their35

contribution. In this setting, there is no difference between each agent having its own controller, or36

viewing them as pieces of a larger model controlling all agents. Taking the latter perspective, our37

controller is a large feed-forward neural network that maps inputs for all agents to their actions, each38

agent occupying a subset of units. A specific connectivity structure between layers (a) instantiates the39

broadcast communication channel between agents and (b) propagates the agent state in the manner of40

an RNN.41

Because the agents will receive reward, but not necessarily supervision for each action, reinforcement42

learning is used to maximize expected future reward. We explore two forms of communication within43

the controller: (i) discrete and (ii) continuous. In the former case, communication is an action, and44

will be treated as such by the reinforcement learning. In the continuous case, the signals passed45

between agents are no different than hidden states in a neural network; thus credit assignment for the46

communication can be performed using standard backpropagation (within the outer RL loop).47

We use policy gradient [33] with a state specific baseline for delivering a gradient to the model.48

Denote the states in an episode by s(1), ..., s(T), and the actions taken at each of those states49

as a(1), ..., a(T), where T is the length of the episode. The baseline is a scalar function of the50

states b(s, ✓), computed via an extra head on the model producing the action probabilities. Beside51

maximizing the expected reward with policy gradient, the models are also trained to minimize the52

distance between the baseline value and actual reward. Thus, after finishing an episode, we update53

the model parameters ✓ by54

✓ =

TX log p(a(t)|s(t), ✓)

✓

TX

r(i) b(s(t), ✓)

✓

TX

r(i) b(s(t), ✓)

2

.

2 Problem Formulation33

We consider the setting where we have M agents, all cooperating to maximize reward R in some34

environment. We make the simplifying assumption that each agent receives R, independent of their35

contribution. In this setting, there is no difference between each agent having its own controller, or36

viewing them as pieces of a larger model controlling all agents. Taking the latter perspective, our37

controller is a large feed-forward neural network that maps inputs for all agents to their actions, each38

agent occupying a subset of units. A specific connectivity structure between layers (a) instantiates the39

broadcast communication channel between agents and (b) propagates the agent state in the manner of40

an RNN.41

Because the agents will receive reward, but not necessarily supervision for each action, reinforcement42

learning is used to maximize expected future reward. We explore two forms of communication within43

the controller: (i) discrete and (ii) continuous. In the former case, communication is an action, and44

will be treated as such by the reinforcement learning. In the continuous case, the signals passed45

between agents are no different than hidden states in a neural network; thus credit assignment for the46

communication can be performed using standard backpropagation (within the outer RL loop).47

We use policy gradient [33] with a state specific baseline for delivering a gradient to the model.48

Denote the states in an episode by s(1), ..., s(T), and the actions taken at each of those states49

as a(1), ..., a(T), where T is the length of the episode. The baseline is a scalar function of the50

states b(s, ✓), computed via an extra head on the model producing the action probabilities. Beside51

maximizing the expected reward with policy gradient, the models are also trained to minimize the52

distance between the baseline value and actual reward. Thus, after finishing an episode, we update53

the model parameters ✓ by54

✓ =

TX

t=1

log p(a(t)|s(t), ✓)

✓

TX

i=t

r(i) b(s(t), ✓)

✓

TX

i=t

r(i) b(s(t), ✓)

2

.

Here r(t) is reward given at time t, and the hyperparameter is for balancing the reward and the55

baseline objectives, set to 0.03 in all experiments.56

3 Model57

We now describe the model used to compute p(a(t)|s(t), ✓) at a given time t (ommiting the time58

index for brevity). Let sj be the jth agent’s view of the state of the environment. The input to the59

tanh

email

Abstract

abstract

roduction

ork we make two contributions. First, we simplify and extend the graph neural network

ure of ??. Second, we show how this architecture can be used to control groups of cooperating

del

lest form of the model consists of multilayer neural networks fi

that take as input vectors

and output a vector hi+1

. The model takes as input a set of vectors {h0

1, h0

2, ..., h0

m}, and

s

hi+1

j = fi

(hi

j, ci

j)

ci+1

j =

X

j06=j

hi+1

j0 ;

0

j = 0 for all j, and i 2 {0, .., K} (we will call K the number of hops in the network).

d, we can take the final hK

j and output them directly, so that the model outputs a vector

nding to each input vector, or we can feed them into another network to get a single vector or

tput.

CommNet modelth communication stepModule for agent

email

Abstract

abstract

Introduction

n this work we make two contributions. First, we simplify and extend the graph neural network

rchitecture of ??. Second, we show how this architecture can be used to control groups of cooperating

gents.

Model

he simplest form of the model consists of multilayer neural networks fi

that take as input vectors

i

and ci

and output a vector hi+1

. The model takes as input a set of vectors {h0

1, h0

2, ..., h0

m}, and

omputes

hi+1

j = fi

(hi

j, ci

j)

ci+1

j =

X

j06=j

hi+1

j0 ;

We set c0

j = 0 for all j, and i 2 {0, .., K} (we will call K the number of hops in the network).

desired, we can take the final hK

j and output them directly, so that the model outputs a vector

orresponding to each input vector, or we can feed them into another network to get a single vector or

calar output.

email

Abstract

abstract1

1 Introduction2

In this work we make two contributions. First, we simplify and extend the graph neural network3

architecture of ??. Second, we show how this architecture can be used to control groups of cooperating4

agents.5

2 Model6

The simplest form of the model consists of multilayer neural networks fi

that take as input vectors7

hi

and ci

and output a vector hi+1

. The model takes as input a set of vectors {h0

1, h0

2, ..., h0

m}, and8

computes9

hi+1

j = fi

(hi

j, ci

j)

10

ci+1

j =

X

j06=j

hi+1

j0 ;

We set c0

j = 0 for all j, and i 2 {0, .., K} (we will call K the number of hops in the network).11

If desired, we can take the final hK

j and output them directly, so that the model outputs a vector12

corresponding to each input vector, or we can feed them into another network to get a single vector or13

scalar output.14

email

Abstract

abstract1

1 Introduction2

In this work we make two contributions. First, we simplify and extend the graph neural n3

architecture of ??. Second, we show how this architecture can be used to control groups of coop4

agents.5

2 Model6

The simplest form of the model consists of multilayer neural networks fi

that take as input7

hi

and ci

and output a vector hi+1

. The model takes as input a set of vectors {h0

1, h0

2, ..., h0

m8

computes9

hi+1

j = fi

(hi

j, ci

j)

10

ci+1

j =

X

j06=j

hi+1

j0 ;

We set c0

j = 0 for all j, and i 2 {0, .., K} (we will call K the number of hops in the ne11

If desired, we can take the final hK

j and output them directly, so that the model outputs a12

corresponding to each input vector, or we can feed them into another network to get a single v13

scalar output.14

their actions, each agent occupying a subset of units. A specific connectivity structure between layers

(a) instantiates the broadcast communication channel between agents and (b) propagates the agent

state.

3 Communication Model

We now describe the model used to compute p(a(t)|s(t), ✓) at a given time t (omitting the time

index for brevity). Let sj be the jth agent’s view of the state of the environment. The input to the

controller is the concatenation of all state-views s = {s1, ..., sJ }, and the controller is a mapping

a = (s), where the output a is a concatenation of discrete actions a = {a1, ..., aJ } for each agent.

Note that this single controller encompasses the individual controllers for each agents, as well as

the communication between agents.

3.1 Controller Structure

We now detail our architecture for that allows communication without losing modularity. is built

from modules fi

, which take the form of multilayer neural networks. Here i 2 {0, .., K}, where K

is the number of communication steps in the network.

Each fi

takes two input vectors for each agent j: the hidden state hi

j and the communication ci

j,

and outputs a vector hi+1

j . The main body of the model then takes as input the concatenated vectors

h0

= [h0

1, h0

2, ..., h0

J ], and computes:

Connecting Neural Models

Connecting Neural Models

Connecting Neural Models

Anonymous Author(s)

Affiliation

Address

2 Problem Formulation33

We consider the setting where we have M agents, all cooperating to maximize rewa34

environment. We make the simplifying assumption that each agent receives R, indepe35

contribution. In this setting, there is no difference between each agent having its own36

viewing them as pieces of a larger model controlling all agents. Taking the latter pe37

controller is a large feed-forward neural network that maps inputs for all agents to thei38

agent occupying a subset of units. A specific connectivity structure between layers (a) i39

2 Problem Formulation33

We consider the setting where we have M agents, all cooperating to maximize reward R in some34

environment. We make the simplifying assumption that each agent receives R, independent of their35

contribution. In this setting, there is no difference between each agent having its own controller, or36

viewing them as pieces of a larger model controlling all agents. Taking the latter perspective, our37

controller is a large feed-forward neural network that maps inputs for all agents to their actions, each38

agent occupying a subset of units. A specific connectivity structure between layers (a) instantiates the39

broadcast communication channel between agents and (b) propagates the agent state in the manner of40

an RNN.41

Because the agents will receive reward, but not necessarily supervision for each action, reinforcement42

learning is used to maximize expected future reward. We explore two forms of communication within43

the controller: (i) discrete and (ii) continuous. In the former case, communication is an action, and44

will be treated as such by the reinforcement learning. In the continuous case, the signals passed45

between agents are no different than hidden states in a neural network; thus credit assignment for the46

ecting Neural Models2 Problem Formulation33

We consider the setting where we have M agents, all cooperating to maximize reward R in some34

onnecting Neural Models2 Problem Formulation33

We consider the setting where we have M agents, all cooperating to maximize reward R in some34

Connecting Neural Models

Anonymous Author(s)

Affiliation

Address

email

Connecting Neural Models

Anonymous Author(s)

Affiliation

Address

email

Connecting Neural Models

Anonymous Author(s)

Affiliation

Address

email

Connecting Neural Models

Anonymous Author(s)

Affiliation

Address

email

Figure 1: An overview of our CommNet model. Left: view of module fi

for a single agent j. Note

Learning Multiagent Communication with Backpropagation,

Sainbayar Sukhbaatar, Arthur Szlam, Rob Fergus, NIPS 2016](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pfxseminar170309forslideshare-170708083116/85/Learning-Communication-with-Neural-Networks-5-320.jpg)

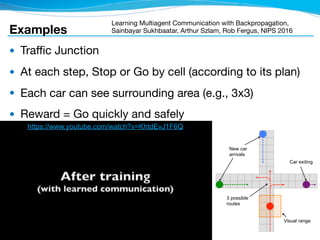

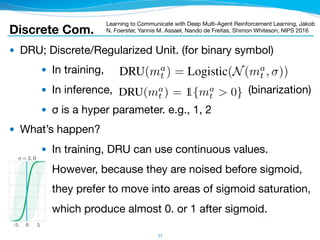

![Discrete Com.

● Communication of (discrete) binary sequences

● Each agent outputs an action a after com. steps

● DQN. In training,

● (a) RIAL uses binary com.

● (b) DIAL uses noisy continuous com. = DRU

9

Learning to Communicate with Deep Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning, Jakob

N. Foerster, Yannis M. Assael, Nando de Freitas, Shimon Whiteson, NIPS 2016

Q-network represents Qa

(oa

t , ma

t 1, ha

t 1, ua

), which conditions on that agent’s individual hidden

state ha

t 1 and observation oa

t as well as messages from other agents ma0

t 1.

To avoid needing a network with |U||M| outputs, we split the network into Qa

u and Qa

m, the Q-values

for the environment and communication actions, respectively. Similarly to [18], the action selector

separately picks ua

t and ma

t from Qu and Qm, using an ✏-greedy policy. Hence, the network requires

only |U| + |M| outputs and action selection requires maximising over U and then over M, but not

maximising over U ⇥ M.

Both Qu and Qm are trained using DQN with the following two modifications, which were found to be

essential for performance. First, we disable experience replay to account for the non-stationarity that

occurs when multiple agents learn concurrently, as it can render experience obsolete and misleading.

Second, to account for partial observability, we feed in the actions u and m taken by each agent

as inputs on the next time-step. Figure 1(a) shows how information flows between agents and the

environment, and how Q-values are processed by the action selector in order to produce the action,

ua

t , and message ma

t . Since this approach treats agents as independent networks, the learning phase is

not centralised, even though our problem setting allows it to be. Consequently, the agents are treated

exactly the same way during decentralised execution as during learning.

ot

1

ut+1

2

Q-Net

ut

1

Q-Net

Action

Select

mt

1

mt+1

2

Agent1Agent2

ot+1

2

Action

Select

mt-1

2

Environment

Q-Net

Action

Select

Q-Net

Action

Select

t+1t

(a) RIAL - RL based communication

ot

1

ut+1

2

C-Net

ut

1

C-Net

Action

Select

DRU

mt

1

mt+1

2

Agent1Agent2

ot+1

2

Action

Select

Environment

C-Net

Action

Select

C-Net

Action

Select

DRU

t+1t

(b) DIAL - Differentiable communication](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pfxseminar170309forslideshare-170708083116/85/Learning-Communication-with-Neural-Networks-9-320.jpg)

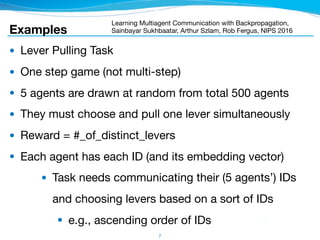

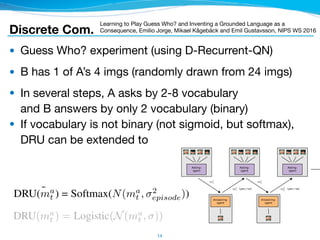

![Discrete Com.

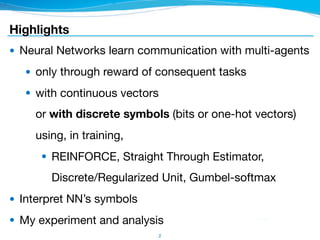

● Multi-Step MNIST; Two players with each MNIST image

● Each sends each image’s number (0-9)

by binary x 4 steps (= 4bit = can represent 16 patterns)

● Reward = prediction

● Learned to represent 0-9 by 4bit →

10

Learning to Communicate with Deep Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning, Jakob

N. Foerster, Yannis M. Assael, Nando de Freitas, Shimon Whiteson, NIPS 2016

y outperforming the NoComm baseline. DIAL with param-

e substantially faster than RIAL. Furthermore, parameter

b) shows results for n = 4 agents. DIAL with parameter

ods. In this setting, RIAL without parameter sharing was

se results illustrate how difficult it is for agents to learn the

ameter sharing can be crucial for learning to communicate.

dicating that the gradient provides a richer and more robust

he communication protocol discovered by DIAL for n = 3

re 4(c) shows a decision tree corresponding to an optimal

rogation room after day two, there are only two options:

ted the room before. If three prisoners had been, the third

The other options can be encoded via the “On” and “Off”

d on the well known MNIST digit classification dataset [25].

u1

2

m1 m2 m3 m4

u1

1

u5

1

u5

2

… … …

… … …

… … …

Agent1Agent2

m1

…

…

u1

2

u1

1

u2

2

u2

1

Agent1Agent2

Figure 5: MNIST games architectures.

r

e

n

d

s

c

-

e

e

g

a) Evaluation of Multi-Step (b) Evaluation of Colour-Digit

1 2 3 4

6teS

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

7rueDigit(c) Protocol of Multi-Step

10N 20N 30N 40N 50N

# (SRchs

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1Rrm.R(2StLmDO)

DIAL

DIAL-16

5IAL

5IAL-16

1RCRmm

2rDcOe

(a) Evaluation of Multi-Step (b) Evaluation of Colour-Digit (c) P

Figure 6: MNIST Games: (a,b) Performance of DIAL and RIAL, with and with

-NS: no parameter sharing](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pfxseminar170309forslideshare-170708083116/85/Learning-Communication-with-Neural-Networks-10-320.jpg)

![Discrete Com.

● Multi-Step MNIST; Two players with each MNIST image

● Each sends each image’s number (0-9)

by binary x 4 steps (= 4bit = can represent 16 patterns)

● Reward = prediction

● Learned to represent 0-9 by 4bit →

12

Learning to Communicate with Deep Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning, Jakob

N. Foerster, Yannis M. Assael, Nando de Freitas, Shimon Whiteson, NIPS 2016

y outperforming the NoComm baseline. DIAL with param-

e substantially faster than RIAL. Furthermore, parameter

b) shows results for n = 4 agents. DIAL with parameter

ods. In this setting, RIAL without parameter sharing was

se results illustrate how difficult it is for agents to learn the

ameter sharing can be crucial for learning to communicate.

dicating that the gradient provides a richer and more robust

he communication protocol discovered by DIAL for n = 3

re 4(c) shows a decision tree corresponding to an optimal

rogation room after day two, there are only two options:

ted the room before. If three prisoners had been, the third

The other options can be encoded via the “On” and “Off”

d on the well known MNIST digit classification dataset [25].

u1

2

m1 m2 m3 m4

u1

1

u5

1

u5

2

… … …

… … …

… … …

Agent1Agent2

m1

…

…

u1

2

u1

1

u2

2

u2

1

Agent1Agent2

Figure 5: MNIST games architectures.

r

e

n

d

s

c

-

e

e

g

a) Evaluation of Multi-Step (b) Evaluation of Colour-Digit

1 2 3 4

6teS

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

7rueDigit(c) Protocol of Multi-Step

10N 20N 30N 40N 50N

# (SRchs

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1Rrm.R(2StLmDO)

DIAL

DIAL-16

5IAL

5IAL-16

1RCRmm

2rDcOe

(a) Evaluation of Multi-Step (b) Evaluation of Colour-Digit (c) P

Figure 6: MNIST Games: (a,b) Performance of DIAL and RIAL, with and with

-NS: no parameter sharing](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pfxseminar170309forslideshare-170708083116/85/Learning-Communication-with-Neural-Networks-12-320.jpg)

, which is used to approximate the agent’s action-observation history.

ly, the output ha

2,t of the top GRU layer, is passed through a 2-layer MLP Qa

t , ma

t =

[128, 128, (|U| + |M|)](ha

2,t).

Switch Riddle

Day 1

3 2 3 1

Off

On

Off

On

Off

On

Day 2 Day 3 Day 4

Switch:

Action: On None None Tell

Off

On

Prisoner

in IR

:

Figure 3: Switch: Every day one pris-

oner gets sent to the interrogation room

where he sees the switch and chooses

from “On”, “Off”, “Tell” and “None”.

first task is inspired by a well-known riddle described

llows: “One hundred prisoners have been newly

red into prison. The warden tells them that starting

rrow, each of them will be placed in an isolated cell,

le to communicate amongst each other. Each day,

warden will choose one of the prisoners uniformly

ndom with replacement, and place him in a central

rogation room containing only a light bulb with a

e switch. The prisoner will be able to observe the

nt state of the light bulb. If he wishes, he can toggle

ght bulb. He also has the option of announcing that he believes all prisoners have visited the

rogation room at some point in time. If this announcement is true, then all prisoners are set free,

it is false, all prisoners are executed[...]” [24].

itecture. In our formalisation, at time-step t, agent a observes oa

t 2 {0, 1}, which indicates if

gent is in the interrogation room. Since the switch has two positions, it can be modelled as a

message, ma

t . If agent a is in the interrogation room, then its actions are ua

t 2 {“None”,“Tell”};

wise the only action is “None”. The episode ends when an agent chooses “Tell” or when the

mum time-step, T, is reached. The reward rt is 0 unless an agent chooses “Tell”, in which

it is 1 if all agents have been to the interrogation room and 1 otherwise. Following the riddle

ition, in this experiment ma

is available only to the agent a in the interrogation room. Finally,

ion of n = 3 (b) Evaluation of n = 4

Off

Has Been?

On

Yes

No

None

Has Been?

Yes

No Switch?

On

On

Off

Tell

On

Day

1

2

3+

(c) Protocol of n = 3

h: (a-b) Performance of DIAL and RIAL, with and without ( -NS) parameter sharing,

Discrete Com.

Learning to Communicate with Deep Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning, Jakob

N. Foerster, Yannis M. Assael, Nando de Freitas, Shimon Whiteson, NIPS 2016](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pfxseminar170309forslideshare-170708083116/85/Learning-Communication-with-Neural-Networks-13-320.jpg)

![● (This is my opinion, not the authors’ one.)

● This

is similar to Gumbel-softmax.

● Two noise distributions are also similar?

15

Discrete Com.

Learning to Play Guess Who? and Inventing a Grounded Language as a

Consequence, Emilio Jorge, Mikael Kågebäck and Emil Gustavsson, NIPS WS 2016

oes from top to bottom. The green boxes illustrate the internal state of the

a human perspective since we communicate through words which are no

ma

t is passed through a variant of DRU as described in section 2.3 to gene

using ˆmt

a =DRU(ma

t ) = Softmax(N(ma

t , 2

episode)) in the training case w

dimensional normal distribution. During evaluation ˆmt

a(i) = {1 if i =

is used instead.

malization (see, [7]) is performed in the MLP for the image embedding and o

ma0

t 1. During testing non-stochastic versions of batch normalization is used

g averages of values observed during training are used instead of those fro

the parameters of the network are performed as described in section 2.3 wi

n [2, Appendix A].

easing noise

y curriculum learning described in [8], where Bengio et al. show that gradu

Categorical Reparameterization with Gumbel-Softmax, Eric Jang, Shixiang Gu, Ben Poole, ICLR 2017

The Concrete Distribution: A Continuous Relaxation of Discrete Random Variables, Chris J. Maddison,

Andriy Mnih, Yee Whye Teh, ICLR 2017

RIVING THE DENSITY OF THE GUMBEL-SOFTMAX DI

derive the probability density function of the Gumbel-Softmax d

1, ..., ⇡k and temperature ⌧. We first define the logits xi = log ⇡

, where gi ⇠ Gumbel(0, 1). A sample from the Gumbel-Softmax c

yi =

exp ((xi + gi)/⌧)

Pk

j=1 exp ((xj + gj)/⌧)

for i = 1, ..., k

ENTERED GUMBEL DENSITY

ping from the Gumbel samples g to the Gumbel-Softmax sample y

ation of the softmax operation removes one degree of freedom. To

equivalent sampling process that subtracts off the last element, (

B DERIVING THE DENSITY

Here we derive the probability dens

bilities ⇡1, ..., ⇡k and temperature ⌧

g1, ..., gk, where gi ⇠ Gumbel(0, 1).

yi =

exp

Pk

j=1

B.1 CENTERED GUMBEL DENSIT

The mapping from the Gumbel samp

2.1 GUMBEL-SOFTMAX ESTIMATOR

The Gumbel-Softmax distribution is smooth, an

respect to their parameters ⇡. Thus, by replacing

we can use backpropagation to compute gradien

replacing non-differentiable categorical samples

as the Gumbel-Softmax estimator.

1

The Gumbel(0, 1) distribution can be sampled

Uniform(0, 1) and computing g = log( log(u)).

egorical random

expected value

Softmax distrib

temperatures, G

2.1 GUMBEL

The Gumbel-S

respect to their

we can use ba

replacing non-

as the Gumbel

1

The Gumbe

Uniform(0, 1) a

o samples from a categorical distribution as ⌧ ! 0. At higher

ples are no longer one-hot, and become uniform as ⌧ ! 1.

TOR

s smooth, and therefore has a well-defined gradient @y/@⇡, with

by replacing categorical samples with Gumbel-Softmax samples

mpute gradients (see Section 3.1). We denote this procedure of

ical samples with a differentiable approximation during training

n be sampled using inverse transform sampling by drawing u ⇠

g( log(u)).

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pfxseminar170309forslideshare-170708083116/85/Learning-Communication-with-Neural-Networks-15-320.jpg)

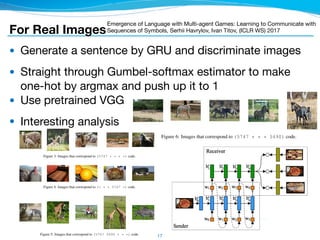

![For Real Images

● SENDER Sends 1 symbol from 10~100 vocabulary

and RECEIVER chooses 1 of 2 imgs

● 2 imgs have different label (in 100 labels)

● Use pretrained VGGNet

● Succeeded to discriminate.

But, some models made strange com.

using only 2 symbols

16

Under review as a conference paper at ICLR 2017

informed senderagnostic sender receiver

symbol

1

symbol

2

symbol

3

symbol

1

symbol

2

symbol

3

left

image

right

image

Under review as a conference paper at ICLR 2017

0.00

0.03

0.06

0.09

2 10152025 38 100

Singular Value Position

NormalizedSpectrum

Figure 2: Left: Communication success as a function of training iterations for the configurations

using fc visual representations. The plots report performance on 1/10 of the test set. Right: Singular

values of symbols used by the informed sender (configuration as in row 2 of Table 1).

id sender vis voc used comm purity (%) obs-chance

rep size symbols success (%) purity (%)

1 informed sm 100 58 100 46 0.27

2 informed fc 100 38 100 41 0.23

3 informed sm 10 10 100 35 0.18

4 informed fc 10 10 100 32 0.17

5 agnostic sm 100 2 99 21 0.15

6 agnostic fc 10 2 99 21 0.15

7 agnostic sm 10 2 99 20 0.15

8 agnostic fc 100 2 99 19 0.15

Multi-Agent Cooperation and the Emergence of (Natural) Language, Angeliki

Lazaridou, Alexander Peysakhovich, Marco Baroni, ICLR 2017

Under review as a conference p

agnostic sender

symbol

1

symbol

2

symbol

3

F

the symbol and image embedd

better denoted by the symbol.

temperature ⌧) and the receive

General Training Details W

mensionality of all embedding

sender: 20, temperature of all

100 symbols. The sender and

the game. The only supervisio

at the right referent. This setup

1998). As outlined in Section

policy r(iL, iR, s(✓S(iL, iR, t)

IE˜r[R(˜r)] where R is the rew

are updated through the Reinfo](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pfxseminar170309forslideshare-170708083116/85/Learning-Communication-with-Neural-Networks-16-320.jpg)

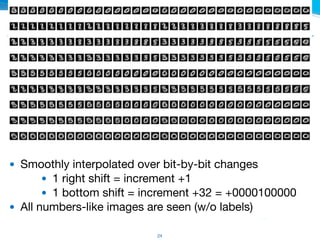

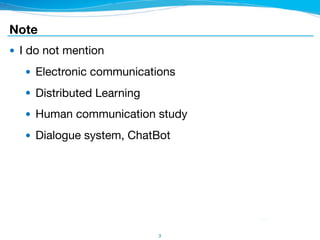

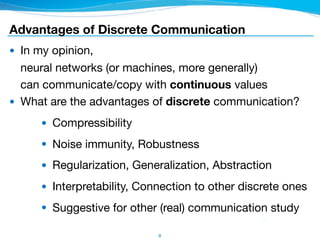

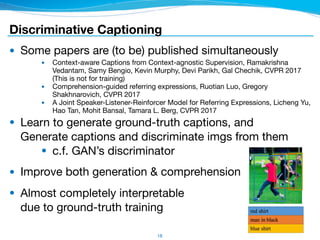

![My Experiments - Result

● Reconstructed Image (Top)

● Raw Image (Bottom)

● Sent sentences

● 0 [1111001011] 6 [0111110101] 9 [0010110011] 0 [1111001101]

1 [0000000100] 5 [1110010010] 9 [0101101111] 7 [0000011110]

3 [1110000101] 4 [0011011010]

● Almost succeed to send image by 10 bits

● with some confusion. 3 or 5, 9 or 4, 0 or 8

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pfxseminar170309forslideshare-170708083116/85/Learning-Communication-with-Neural-Networks-20-320.jpg)