The Statue of Liberty: A Buried Legacy

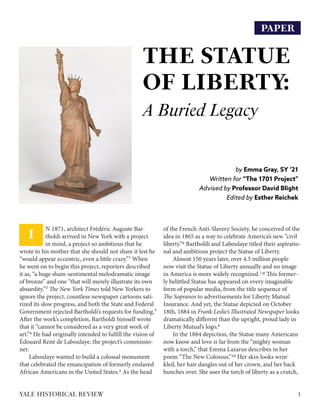

- 1. PAPER THE STATUE OF LIBERTY: A Buried Legacy by Emma Gray, SY ‘21 Written for “The 1701 Project” Advised by Professor David Blight Edited by Esther Reichek 1YALE HISTORICAL REVIEW N 1871, architect Frédéric Auguste Bar- tholdi arrived in New York with a project in mind, a project so ambitious that he wrote to his mother that she should not share it lest he “would appear eccentric, even a little crazy.”1 When he went on to begin this project, reporters described it as, “a huge sham-sentimental melodramatic image of bronze” and one “that will merely illustrate its own absurdity.”2 The New York Times told New Yorkers to ignore the project, countless newspaper cartoons sati- rized its slow progress, and both the State and Federal Government rejected Bartholdi’s requests for funding.3 After the work’s completion, Bartholdi himself wrote that it “cannot be considered as a very great work of art.”4 He had originally intended to fulfill the vision of Édouard René de Laboulaye, the project’s commissio- ner. Laboulaye wanted to build a colossal monument that celebrated the emancipation of formerly enslaved African Americans in the United States.5 As the head of the French Anti-Slavery Society, he conceived of the idea in 1865 as a way to celebrate America’s new “civil liberty.”6 Bartholdi and Laboulaye titled their aspiratio- nal and ambitious project the Statue of Liberty. Almost 150 years later, over 4.5 million people now visit the Statue of Liberty annually and no image in America is more widely recognized.7,8 This former- ly belittled Statue has appeared on every imaginable form of popular media, from the title sequence of The Sopranos to advertisements for Liberty Mutual Insurance. And yet, the Statue depicted on October 18th, 1884 in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper looks dramatically different than the upright, proud lady in Liberty Mutual’s logo.9 In the 1884 depiction, the Statue many Americans now know and love is far from the “mighty woman with a torch,” that Emma Lazarus describes in her poem “The New Colossus.”10 Her skin looks wrin- kled, her hair dangles out of her crown, and her back hunches over. She uses the torch of liberty as a crutch, I

- 2. Left, “Liberty Mutual,” First Financial Federal Credit Union, Accessed March 20, 2020; Right, “The Statue of Liberty in New York,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, October 18, 1884. supporting her weight on its flame. With her free hand, she weakly holds out a box for donations that is inscri- bed with the words: “For something to stand on.” The meaning of this phrase can be interpreted in two ways. When Bartholdi and Laboulaye first pitched their idea to their American supporters, the Americans agreed that if the French funded the construction of the statue, Americans would pay for its pedestal and foundation.11 By 1884, twenty years had passed since the inception of Bartholdi and Laboulaye’s vision, and the American Committee of the Statue of Liberty, tasked with raising money for the pedestal, had failed to raise the necessary funds.12 Thus, Americans quite literally needed to soli- cit money so that the Statue, which Bartholdi comple- ted by 1884, had a pedestal to stand on. Americans expressed growing concern that they would humiliate themselves by having to reject the French gift for lack of funds. It became clear to those in charge that in order to raise funds, they had to convince Americans that the project and the ideas it stood for deserved their well-earned dollars. The project thus also needed a popular, ideological platform to stand on, an ideal that all could agree on. Though Laboulaye and Bartholdi originally wanted that ideal to be emancipa- tion, Americans could not come together to celebrate equal rights for African Americans by the 1880’s. By this time, Reconstruction had ended and the Republi- can agenda had shifted away from the rhetoric of pro- tecting freed Black men. Thus, the Statue of Liberty, as depicted in 1884, sacrifices her flame of liberty, extin- guishing it in an attempt to get her balance. She holds out her hand for money using whatever platform she thinks will appeal to the American people. This cartoon serves as a reminder that the meaning of the Statue shif- ted over time, from a commemoration of emancipation, to a glorification of the American Revolution, to a sym- bol of reconciliation, and ultimately to a celebration of immigration, in order to appeal to the US citizen and his checkbook. Although no longer evident, Laboulaye and Bar- tholdi originally designed the Statue of Liberty as an ode to emancipation and to the Union’s victory. Though French, the “undisputed father of the statue,” Labou- laye, had always been an admirer and a close observer of all things American.13,14 In fact, he wrote a three volume history of the United States before ever visiting.15,16 In 1865, for example, he published the Political History of the United States, from 1620-1789 and wrote an analysis of President James Buchanan’s message on Bleeding Kansas.17,18 The ser- mons of Reverend Ellergy Channing greatly shaped this French man’s views on America and American slavery. 2 THE STATUE OF LIBERTY

- 3. Channing, a Unitarian minister from Boston, wrote and preached about man’s divine nature and the necessity of emancipating all enslaved men.19 Laboulaye thereaf- ter believed in a personal God who liberated all men. Religion informed his abolitionist views and he greatly admired artistic depictions of Christ freeing slaves from their chains, such as Ary Scheffer’s Christ the Consoler.20 Channing’s writings, as well as encounters with Gaspa- rin Martin and other abolitionists, inspired Laboulaye’s vehement hatred of American slavery.21 Laboulaye did not keep his views about emancipa- tion to himself. After the outbreak of the Civil War, he became deeply concerned with the war’s outcome and did everything in his power to support the Union.22 He used his position as a teacher at the Collège de France to give radical, pro-Union lectures in 1863. He asked his students, “Why is it that this friendship has eroded? Why is it that the face of America is not so dear to us as it was in those days?” and answered, “It is due to slave- ry; we had always hoped that something would be done to put an end to an institution which was regarded by the founders of the Constitution as fraught with peril to the country; but instead of this, the partisans of slavery, having obtained the ascendant, have continually been engaged in efforts to perpetuate it and extend its limits, so that we have ceased to feel the same interest in Ame- ricans.”23 Laboulaye subtly threatened Americans by insinuating that they would lose French support and camaraderie if they did not abolish slavery. In the same year, Laboulaye wrote the article which would make a name for him in America. In it, he descri- bed how he had “been watching with interest the course of this country in its more important tendencies, and particularly as related to slavery.”24 He went on to com- pare the suffering that the Civil War brought on Ameri- cans to the cotton famine in Europe in order to appeal to the French and gain their sympathy. He argued that Europeans should not intervene, especially not on the 3YALE HISTORICAL REVIEW Christ the Consoler by Ary Scheffer. “Christ the Consoler,” Oil Paintings Gallery, accessed April 16, 2020.

- 4. side of the Confederacy. Rather, he suggested that Eu- ropeans could best help by stating their support for the Union. He explained that, “It is evident that the South has all the wrong on its side,” because it “breaks the na- tional unity and tears the country into two parts.”25 He believed that the South “has no right to the sympathy of the French nation,” and “As to the canonization of slavery, that must be left to southern preachers.”26 He implicated Americans, explaining how “in the full light of the nineteenth century, [they] audaciously proclaim their desire to perpetuate and extend slavery.”27 With this article, he opposed Napoleon III and the majority of French citizens who sympathized with the Confe- deracy.28 He definitively proclaimed, “The friends of liberty had pronounced themselves boldly against the policy of slavery.” From early on, Laboulaye associated the word “liberty” with emancipation and fought for the American slave’s freedom.29 After the publication of this article, Laboulaye gained a great deal of attention and became even more active in his support for the Union. He wrote letters to abolitionists in the United States and created pamphlets defending the Union cause.30,31 He traveled across France giving talks on universal education and indivi- dual emancipation.32 Inspired by Channing, he wanted to play the part of the Boston reformer in Paris.33 In 1865, he became the head of the French Anti-Slave- ry society and became a member of the Philadelphia branch of the Union League Club, a group dedicated to the new Republican Party and its cause in the Civil War.34 The Club’s support would become very impor- tant to him because of their elite status and connec- tions.35 Laboulaye’s speeches and writing captured the attention of the French public.36 Auguste Nefftzer, a French journalist, explained Laboulaye’s popularity, writing, he “possessed a rare thing in France, the just and lively intelligence of liberty.”37 John Bigelow, an American statesman and aboli- tionist from New York, pronounced in 1888 that La- boulaye’s writings acted as a crucial step in the French government’s decision not to recognize the Confedera- cy.38 Bigelow had travelled to France in 1861, where he had seen that many in Europe had deemed secession a “holy cause.”39 In his 1888 book, he complained that Europeans had “too willing ears to” the “delusive tales,” of the South.40 In Paris, Bigelow read two papers by Laboulaye which pronounced that the South only wit- hdrew in order to perpetuate slavery and that they had no right to separate from the Union.41 When Bigelow asked to meet Laboulaye, the French man responded that he would “be happy to serve in any way a cause which is the cause of liberty and justice.”42 When they met, Bigelow asked the French man whether he could reprint his article in English, to which Laboulaye said, “I am completely at your disposal I shall be charmed to serve a cause which is the cause of all the friends of liberty.” Again, Laboulaye defined the fight for emanci- pation as a fight for “liberty” in this correspondence. Bi- gelow, reflecting later on Laboulaye’s pamphlets, wrote that “the effect…was far greater than I had ventured to anticipate…His pen and his influence were always at our service…Laboulaye’s value as a friend of the Union, and of representative government was not long in being recognized in the United States.”43 Bigelow correctly asserted that Laboulaye made an impact not only in France but also in America. The American press translated and reprinted Laboulaye’s words often and many abolitionist organizations began to see him as a hero. The Union League Club of New York ordered his portrait and the Union League Club in Philadelphia created a bronze bust of him. In fact, Bigelow recounted that by the end of the war, those in the US recognized his name more than those in Eu- rope.44 It is no surprise then that many who ultimately got involved with the Statue of Liberty served first as members of these Union League Clubs.45 Laboulaye ra- dically supported the cause of emancipation and played a significant role in the Civil War. Laboulaye conceived of the idea of for the Statue of Liberty in 1865, the year that the Civil War ended and that John Wilkes Booth assassinated Abraham Lin- coln. The Union victory reinforced Laboulaye’s politi- cal position and inspired him to want to commemorate emancipation. He had begun to praise the prospect of liberty for slaves in 1864 when he wrote, “Rejuvenated by victory, refreshed by trials, America will banish slavery from the world, will set an example still grea- ter than that war of Independence. Twice will she have established liberty; political liberty in 1776, civil liberty in 1864. The world is solidarity and the cause of Ame- rica is the cause of liberty…America disencumbered of slavery, will be the country of all ardent spirits, of all generous hearts.”46 Yet, he never proposed the idea for the Statue until after the Emancipation Proclama- tion. He expressed his excitement about the Proclama- tion in a letter to the United States Secretary of State, 4 THE STATUE OF LIBERTY

- 5. William H. Seward, on January 20th 1866. He wrote to Seward, “The members of the French Emancipa- tion Society have received with emotion and sympathy, the proclamation announcing the abolition of slavery, which you instructed me to communicate to them…It transformed our fathering in a measure into a thanks- giving festival…we beg you to thank the President of the United States in the name of Committee.”47 After Congress passed the 13th Amendment, Laboulaye ex- pressed to his friends at a dinner party that, “If a mo- nument should rise in the United States as a memorial to their independence, I should think it only natural if it were built by united effort.”48 The National Park Ser- vice’s website put its perfectly when it explains that, “With the abolition of slavery and the Union’s victory in the Civil War in 1865, Laboulaye’s wishes of freedom and democracy were turning into a reality in the United States. In order to honor these achievements, Labou- laye proposed that a gift be built for the United States on behalf of France.”49 Laboulaye continued to support emancipated African Americans after they had gained their freedom. He founded a French association for the relief of the newly emancipated slaves and sent funds to newly freed slaves.50,51 He also supported Mrs. Lincoln after she lost her husband. Both he and Bartholdi joined forty thousand other French citizens in contributing money toward a gold medal for Mrs. Lincoln. It read, “Dedicated by French democracy to…honest Lincoln who abolished slavery, re-established the Union and saved the Republic, without veiling the statue of liber- ty.”52 Though they solely meant this phrase, the “statue of liberty,” metaphorically at the time, it is no surprise that this would become the title of the monument they would ultimately build. They chose the word “liberté,” for the title because it has a very specific connotation. Liberté refers to personal liberty, rather than political liberty or liberty from tyranny. Thus, Laboulaye inten- tionally chose a name that would signal a celebration of the enslaved man’s liberty, not the liberty of the United States from Britain’s rule.53 Though Laboulaye wanted to get started imme- diately on his project, the 1870 outbreak of the Franco Prussian War interrupted his plan. 77,000 Frenchmen died in battle in this dramatic stand off against the Ger- mans.54 The commissioner and his prospective sculp- tor continued to discuss their ideas for the project throughout the war. Bartholdi wrote to Laboulaye in 1871 that, “I have spent some time putting my affairs in order,” and that he looked forward to starting the pro- ject so that he could “glorify the Republic and Liberty.”55 Later, many would be claim that these men only started planning the Statue once they had been invited to take part in the 1876 centennial celebration of America’s Re- volution but letters like these, some of which date back to as early as 1867, invalidate that claim. Laboulaye and Bartholdi would later take part in the Centennial but the Civil War, not the American Revolution inspired the creation of the Statue.56,57 Laboulaye encouraged in Bartholdi a strong convic- tion about emancipation. Thus, when Bartholdi first began to design Laboulaye’s commission, he drew his vision from much more violent representations of the fight for freedom.58 He found inspiration in prior per- sonifications of liberty such as Eugène Delacroix’s Li- berty Leading the People (1830).59 Delacroix paints Lady Liberty as a revolutionary figure, holding up the flag of the French Revolution and leading the way for armed, angry men. Bartholdi followed Delacroix’s lead in crea- ting an imagined woman to represent liberty instead of creating a portrait of a specific individual. Another of his inspirations included Ludwig Mi- chael von Schwanthaler’s Bavaria (1848), in which the female personification of the Bavarian homeland holds a sword and raises up a crown.60 Both Bavaria and the Statue of Liberty wear classically draped gowns and have one arm outstretched. He also seemed to have Au- 5YALE HISTORICAL REVIEW Liberty Leading the People by Eugène Delacroix. Alicja Zelazko, “Liberty Leading the People,” Britannica, May 3, 2018

- 6. gustine Dumont’s The Spirit of Freedom on his mind, a statue of Hermes meant to celebrate the 1789 and 1830 revolutions and the location at which many later protests took place.61 Hermes raises a torch in his right hand and broken chains in his left hand.62 The histo- rian Francesca Lidia Viano notes that while Hermes is a naked male with feminine features, the Statue of Liber- ty has been described as a feminine body with male fea- tures.63 The similarities between Bartholdi’s Statue and these older designs emphasizes the revolutionary mea- ning the Statue originally had.Bartholdi and Laboulaye originally tried to use their monument to celebrate the way in which enslaved African Americans threw off their chains to join the Union’s fight. In Bartholdi’s original vision for the Statue of Li- berty, Lady Liberty herself more explicitly represented emancipation. Like Dumont’s Hermes, she held broken shackles in her hands and trampled the chains by her feet.64 Early miniature prototypes of the statue on dis- play at the Museum of the City of New York dated from 1870 showed Liberty’s left arm extended and broken shackles hanging from her wrist.65,66 Yet, as Bartholdi began showing his miniature to others and receiving feedback, he realized that he had to create a less threate- ning image. He turned the Statue’s flaming torch into a peaceful beacon of light and swapped the chains lady liberty held out for a book inscribed with 1776 on the cover.67 The Statue of Liberty we see today no longer reflects Laboulaye and Bartholdi’s original intentions.68 6 THE STATUE OF LIBERTY Left: Bavaria by Ludwig Schwanthaler. Berenson, The Statue of Liberty, 19; Right: The Spirit of Freedom by Augstin Dumont. Banerjee, “The Spirit of Freedom.” Early prototype of the Statue of Liberty. Turley, “Myths Surrounding the Origin of the Statue of Liberty.”

- 7. Bartholdi’s ultimate creation still retains some hints of Lady Liberty’s original interpretation. He based the Statue on the roman goddess Libertas, usually depicted wearing a Phrygian cap worn by freed Roman slaves.69 Further, although she now holds a tame torch, the Sta- tue of Liberty still thrusts her arm in the air, in a manner reminiscent to Delacroix’s imagined Lady Liberty. In fact, in Franz Kafka’s Amerika, Karl Rossman mistakes the Statue of Liberty’s torch for a sword.70 The chains by the Statue of Liberty’s feet serve as the only explicit reminder of the Statue’s original meaning. Though the representation of someone becoming unchained has acted as a symbol for emancipation since ancient times, these chains are nearly invisible beneath her drapery to- day.71,72,73 The location chosen for the statue itself hints at its significance. Bedloe’s Island, now known as Liber- ty Island, served as an ammunition depot and recrui- ting station for the Union army during the Civil War.74 Bartholdi, limited by the need for funds, still found ways to embed the Statue of Liberty with revolutionary meaning.75 Bartholdi and Laboulaye attempted to commemo- rate the Union victory in a nation that still struggled with how best to remember the Civil War. Americans began shaping the memory of the Civil War before it had even finished.76 Those who watched countless lo- ved ones die, wanted to believe that they had sacrificed their lives for a reason. Writers like Frederick Douglass and Walt Whitman spent countless pages trying to make sense of the bloodshed. As early as the Gettysburg address, President Abraham Lincoln urged Americans to make sure men did not die in vain and told them to fuel a new nation using the “wreckage of the war.”77 African Americans hoped that Union victory, no matter how much it cost, would mean equality for them at last. These hopes for equality, however, would not come to fruition by the end of the Reconstruction period (1865- 1877). By 1870, all of the ex-Confederate states had re- joined the Union and by the compromise of 1877, the North had given up trying to impose equality for black Americans. Democrats allowed Rutherford B. Hayes to win the Presidency and in return Republicans withdrew all federal troops from the South, leaving the Southern states to disenfranchise and discriminate against Afri- can Americans. This post-Reconstruction period held very different meanings for black and white Americans. To African Americans, it signified a great deal of loss. Southern issues began to play an increasingly small part in the politics of Northern Republicans and racist Americans took advantage of this. By 1876, Martin W. Gary called on Democrats to control the black vote with intimida- tion methods in South Carolina.78 In 1883, the Supre- me Court ruled the Civil Rights Act of 1875, integral to protecting the rights of African Americans, unconstitu- tional. As John C. Calhoun proclaimed, the South could now settle “all questions” regarding African Ameri- cans.79 Many Americans did not try to remain discrete about their efforts to disempower African Americans. One North Carolina Democrat wrote in 1875, “It is absolutely necessary…that the county funds shall be placed beyond the reach of the large negro majorities.” 80 One Southern newspaper declared that the 14th and 15th amendments might last but, “we intend…to make them dead letters on the statute-book.”81 As W.E.B. Du Bois articulated how after the Civil War, “the slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.”82 In 1897, Frank Barbour Coffin, a black pharmacist, looked back at what American had becomeandwrote“TheNegro’sAmerica.”Hedescribed, “My country, ‘tis of thee, Sweet land of liberty, would I could sing; It land of Pilgrim’s pride also where lynched men died with such upon her tide, freedom can’t rei- gn.”83 His sentiments reflected those felt by many in the late nineteenth century, who deemed concepts like “li- berty” and “freedom” unattainable fallacies. White Americans, on the other hand, viewed the post-Reconstruction period as a time to celebrate the reconciliation of the nation. In 1876, unprecedented parades and ceremonies broke out in celebration of the Civil War and the unity to which it led. On May 30th, 1877, Colonel A.W. Baxter stood up at the decoration day parade and pronounced that, “over the grave of bu- ried bygones rejoice, now, as soldiers and citizens, we know no North, no South, no East, no West – only one country.”84 He believed that those who went prematu- rely to their graves had done so as a means of bringing the nation back together. He did not specify that the South had fractured that union originally for the pur- pose of retaining the right to own slaves. Instead of cele- brating the freedom of formerly enslaved men, Ameri- cans used decoration day as a time to call for sympathy for the Confederate veteran and to praise newly found reunion.85 Speakers described Reconstruction as a of time great “massacres” and “violations,” villainizing the radical Republicans who had attempted to create equal 7YALE HISTORICAL REVIEW

- 8. opportunities for African Americans. They did not re- cognize the “massacres” that black Americans currently faced in the form of lynching.86 By the time President Wilson gave a speech to commemorate the Gettysburg address 50 years after Lincoln’s, the “wreckage of the war” had certainly not ensured freedom and equality for African Americans. Southern states had stripped blacks of suffrage by requiring voters to pass literacy tests, pay poll taxes, and own property.87 Wilson at- tempted to preach about sectional reconciliation in 1913, but he spoke to a society rampant with inequality. It makes sense then that Laboulaye and Bartholdi qui- ckly abandoned their hope to raise money for a Statue dedicated to emancipation.88 Bartholdi and Laboulaye realized that raising mo- ney in America would prove difficult. Bartholdi arrived in New York in June of 1871, unknown to the Ameri- can public, and tasked with gaining American support for his project.89 He spoke little English, knew barely anything about the United States, and had very few of his own connections. He started by talking to American Francophiles like Mary Louise Boothe but they showed little interest.90 He then traveled across the country from Boston, to Newport, to Chicago, to the Rockies, to San Francisco seeking any support he could find.91 He described his journey as, a “Missionary’s pilgrimage… In each town I look for some people who might wish to participate in our enterprise.”92 He did not venture to the South, clearly aware that an abolitionist message would not gain traction there. He did however meet with many abolitionists, such as Charles Sumner.93 Some supported the project and its original intent, such as Colonel John W Forney, but most did not.94 Barthol- di wrote to his mother, “Each site presents some dif- ficulty but the greatest difficulty, I believe, will be the American character which is hardly open to things of the imagination.”95 Even four years later, newspaper coverage of the Statue reveals that Bartholdi continued to struggle to inspire interest in the project. On September 29th, 1875 the New York Times published an editorial which said, “it is more than doubtful the American public is ready to undertake any such task” of funding the Sta- tue.96 One year later, the Milwaukee Daily Sentinel read, “The plan, originated in France, to erect on Bedloe’s Island…a colossal statue of the Goddess of Liberty, needs to be urged to a certain degree by the people of the United States.”97 Though reporters would later refer to the Statue as “colossal” as a source of pride, at first, the size of the project seemed untenable and overly am- bitious. Americans wanted a more modest statue and did not want to pay for a pedestal that cost as much as the Statue itself.98 Bartholdi and Laboulaye accepted the Milwaukee paper’s advice and realized that they needed 8 THE STATUE OF LIBERTY “Colossal Hand and Torch,” at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition, 1876. Megan Margino, “The Arm that Clutched the Torch: The Statue of Liberty’s Campaign for a Pedestal,” New York Public Library, April 7, 2015.

- 9. to convince the American people to support this statue if they hoped for funding. Laboulaye had long entertained the idea of shaping the Statue’s meaning around what the American public wanted to hear. Even before Bartholdi left, Laboulaye wrote to him, “If you find a happy idea, a plan that will excite public enthusiasm, we are convinced that it will be successful.”99 Half of the nation still did not think of the Union victory as a “happy idea.” Thus, when Bartholdi and Laboulaye received an invitation to join the Centennial celebration, they seized the chance to “excite” Americans. In order to fit into the one-hun- dred-year anniversary of the American Revolution, the sculptor and commissioner pushed aside the divisive memory that led to the Statue’s creation and rethought the Statue’s backstory and meaning. A year after work formally began, the completed torch and left forearm of Lady Liberty, along with a new rendering of the Statue’s significance, went on display in Philadelphia and New York.100 The Centennial exhibition marked the great tech- nological “progress” of the age.101 Over one fifth of the US population attended this celebration, where every- thing from Siamese ivory to a replica of Cleopatra went on display.102 This moment of self-congratulation came at a time in which great turbulence rocked the nation. An economic depression had left millions of workers unemployed and had inspired a great number of strikes including the Long Strike of 1875. The Centennial also took place during a continuing period of discrimina- tion towards African Americans, who could not work for the segregated construction crews that built the ex- hibition halls. Grant had started to pull back on what he called the “ultra-measures relating to the South,” by that point, meaning he stopped enforcing Reconstruc- tion protections. Republicans had “abandoned” African Americans “to the tender mercies of the Ku Klux Klan.”103 The ex- hibition, which had no recognition of the working-class strikes, the violent overthrow of Mississippi Recons- truction, or the scandals engulfing President Grant’s ad- ministration, was no place for a Statue commemorating emancipation.104 After Bartholdi displayed the Statue at the Centen- nial, many believed it had been intended to celebrate the anniversary of America’s freedom from Britain. By 1876, the Milwaukee Daily Sentinel stated the French built the Statue once they “learned of the approach of our Centennial year, and remembering the part of their country in our revolution they were moved to take part in our festival,” a faulty idea that many would la- ter echo.105 In 1881, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat wrote that from the beginning the Statue “was meant to be shown during the Centennial year to honor the revolu- tionary struggle.” The American Committee itself had a hand in ensuring that the Centennial interpretation persisted. The American Committee for the Statue of Liberty, born in 1881, came about as a means of raising funds for the pedestal. According to the Boston Daily Advertiser, the Com- mittee gave a speech in 1881 to raise money in which they claimed that the project had always been meant to “commemorate the hundredth university of our na- tional independence.”106 One year later, the Daily Eve- ning Bulletin recorded that Mr. Evarts, the committee leader, claimed that, “The idea of making this gift was conceived in 1875, as we were approaching the Centen- nial celebration of the Declaration of Independence,” af- ter which he asked for great sums of money.107 In 1883, another Committee member, Richard Butler, said that the Statue “was given by the people of the French Repu- blic to the people of the United States as…an expression of the sympathy of France in the Centennial Anniver- sary of American Independence.” Those raising money for the project took advantage of the Centennial and purposefully reshaped the Statue’s significance.108,109 The Centennial and the press coverage afterward still did not bring in nearly enough funds. Some thought that America would ultimately only receive Lady Liber- ty’s arm, which had gone on display.110 Evarts wrote to Laboulaye in 1881 saying, “I assure you, my dear M. de Laboulaye, that we have no doubt that our compa- triots will joyfully furnish the money for the pedestal,” but by 1882 he did not seem as sure.111 That year, the Daily Evening Bulletin wrote of the “ridicule” that the undertaking faced and the money that trickled in rather slowly.112 The Committee tried inviting citizens, cham- bers of Commerce, Boards of Trade, Mechanics’ Asso- ciations, and Voluntary organizations to take part in what they called their “grand, patriotic enterprise,” but to no avail.113 Though Committee members kept reas- suring Laboulaye that “American people will be only too eager” to donate, the citizens proved them wrong. By 1883, Americans had only raised $85,000 and desperation started to set in.114 The Committee placed “Liberty boxes” across the city that resembled poor 9YALE HISTORICAL REVIEW

- 10. boxes, but even this effort only collected $2,355.115 In- terest from newspapers began to dry up. On November 20th, 1883 The Arkansas Gazette included one sentence on the needed subscriptions sandwiched between two much longer articles about local murder cases.116 Some newspapers started to include information about the Statue in the “Foreign” section, distancing themselves from the project.117 This year also served as a tragic one, as Laboulaye died on May 25th. He would never get to see the completed statue and he would certainly never get to ensure that people knew its original meaning. Af- ter his death, efforts to raise money only became more fraught. In December of that year, the Committee held a pedestal fund art loan exhibition selling Bartholdi’s autograph and displaying manuscripts from people like Mark Twain and Emma Lazarus. As efforts like these continued to fail in America, Bartholdi continued to work diligently on the creation of Lady Liberty in France. In 1884, Bartholdi finished constructing the Statue of Liberty. He wrote, “Let us hope that when you receive this news from France, the patriotic spirit of America will awaken, and that funds will be coming in.”118 Yet, even after Americans watched the first bricks appear on Bedloe’s Island, they remained uninspired. By October of 1884, the Committee had only two thousand dollars left. The North American described how, “During the past six years every effort has been made to induce New Yorkers to contribute the amount needed, and every effort has failed.”119 The article talked about the pres- sure now rising to appease the “liberal people of France who tendered this Statue of Liberty as a token of their good will toward…the United States,” and how bad it would look for “our national courtesy” if America failed to raise the needed money. The article threatened that the French might rescind the gift and “put it to their own uses” if the money is not raised soon. It declared that “the Republicans of France have offered” it “as an expression of their friendliness.” This vague interpreta- tion of the Statue reflects the desperation for funds.120 Anxiety would truly set in the next year though, when a congressional appropriation bill for $100,000 did not pass.121 On March 13th, 1885 the newspaper pu- blisher Joseph Pulitzer wrote that the, “Committee acknowledges its inability to proceed.”122 American newspapers would ultimately save the Statue of Liberty by adopting new rhetoric surrounding the Statue and framing it as a patriotic project. Joseph Pulitzer usually receives all of the credit for this effort and he certainly made a huge impact. Pulitzer step- ped in when the Committee needed $100,000 in the spring of 1885.123 After fighting for the Union army, he had married into a wealthy family. His wealth only in- creased after he bought the St Louis Post Dispatch and the World from Jay Gould.124 Pulitzer had been suppor- tive of the Statue since 1883 when he wrote an editorial saying, “The statue, the noble fight of our young sister republic, is ready for us. And here, in the commercial metropolis…where hundreds of our citizens reckon their wealthy by millions…we stand haggling and beg- ging…to procure a pedestal…New York ought to blush at this humiliating spectacle…As the rich citizens of New York have shown such apathy in this matter, let the poorer classes move.”125 He began raising money in earnest though in 1885. When he reported donations, he credited young office boys, working girls, struggling artists, recent immigrants, school children, and the el- derly. He published the letters of donors such as a young child named Norm Allen who wrote, “I am a little boy. Would like to help you more. I send you my first gold dollar for the Bartholdi Fund.”126 With both his early and later articles, Pulitzer attempted to turn the Statue into not only a matter of patriotism but also a matter of class pride. Pulitzer also perpetuated the centennial unders- tanding of the Statue and its vaguer understandings. In 1885 he wrote, “Money must be raised to complete the pedestal…a gift emblematic of our attainment of the first century of independence…We must raise mo- ney!”127 On March 23, 1885 he wrote, “We ask you in the name of glorious memories, in the name of our country, the name of civilization and of art,” to donate.128 Pu- litzer had great success, raising two thousand dollars in his first week and twenty-five thousand dollars in his first month. He ran editorials every day for sixth mon- ths until he raised his goal of $100,000. Today, a statue of Pulitzer stands on Liberty Island in gratitude for his help.129 If it had not been for his persistence and the extensive range of meanings he attributed to the Statue of Liberty, the Statue would almost certainly not stand on Liberty Island today. Pulitzer usually receives all of the credit for saving Bartholdi’s project but many other newspapers fought for its success. Solicitations for money for the Statue often appeared in the advertisement section of news- papers from across the nation. In 1884, the Milwaukee 10 THE STATUE OF LIBERTY

- 11. Daily Sentinel advertised the Statue, using its Centen- nial interpretation. It described the Statue as a “Memo- rial of the ancient and continued good will of the great nation which so materially aided us in our struggle for freedom,” and then asked readers to donate money to power the electricity of the Statue’s torch. The article explicitly chose to “appeal to…patriotic citizens,” and said that the project, “ought not to be stopped by the indifference or apathy of the people.” It declared confi- dence in the project’s success because “the object of this international sentient of friendship and love of liber- ty,” aligned with the values of Americans. This appeal reeked of desperation as the author admitted that, “The funds of the committee are nearly exhausted; the world must stop within thirty days unless public spirit and pa- triotism is widely aroused to finish it. Indifference to it is tantamount to national ingratitude and humiliation.” The article implicated all Americans and tried to turn the Statue’s funding into a nationalistic project. This article also served as one of the first to project a sectional reconciliation meaning upon the Statue of Li- berty. It went on to say, “Hitherto it [the Statue] has been misrepresented and misunderstood. It is in no way a private enterprise for personal or sectional glorification; it is the gift of the people of France to the people of the United Stated as a recognition of the blessings of liber- ty…It is fitting that its pedestal should be constructed by the contributions of many and not of few. No North, no South, no East, no West, but throughout the glorious land.”130 The author seems to draw directly from Colo- nel Baxter’s 1877 speech, in which he praised reconci- liation and overlooked the atrocities African Americans continued to face. Instead of remembering the Statue as a celebration of emancipation, people began to focus on it as a symbol of American peace and reunion. Si- milar language resounded during the laying of the Sta- tue of Liberty’s first bricks on Bedloe’s that same year. A minister pronounced that the Statue celebrated how, “The American government never suspended the reign of law. It never resorted to prosecutive measures and after the conclusion of the great struggle, it entrusted to liberty the task of healing the wounds caused by the war.”131 Many would follow his example by celebrating reconciliation and villainizing the Radical Republicans, rather than recognizing those who currently stripped African Americans of their liberty. The Statue of Liberty also appeared on newspaper advertisement pages across the country. In 1884, the Southwestern Christian Advocate advertised the “co- lossal statue” on a page filled with ads for Easter cards and Sunday school.132 This paper and many others sold one-dollar miniature statues to raise funds. The adver- tisements read, “This attractive souvenir and Mantel or desk ornament is a perfect facsimile” and also offered a larger model for five dollars. 11 “Multiple Classified Advertisements,” Southwestern Christian Advocate, February 28, 1884. YALE HISTORICAL REVIEW

- 12. The Congregationalist asked for as little as “sums of one dollar” to meet the need and the Rocky Mountain News “respectfully” asked “that one of you will furnish the money to effect this or that two of your or three of you or five of you.” These newspapers, which helped Pulitzer in the fight to raise funds, continued the nar- rative that Bartholdi and Laboulaye had begun at the Centennial.133,134 Their articles advertised the Statue as a celebration of the American revolution and of the French collaboration that ensured the United States’ victory. For example, the Idaho Avalanche told its rea- ders in 1885 that they should donate because “our form of government and the freedom…we owe in part to the French aid and moral assistance during the seven bloody years of the Revolution.”135 Even in the House of Representatives, Congress discussed the project in 1885 as one which “celebrated in the United States” the “hundredth anniversary of national independence.”136 On June 18th, 1886 the committee on foreign affairs re- ported that funds should be provided for the inaugura- tion, because the event commemorated “the centenary of our independence as a nation.”137 Those attempting to raise funds led the charge in changing the meaning of the Statue of Liberty but the government and the ge- neral public quickly followed. Though the rest of the American public eventual- ly accepted its new narratives, the irony of the Statue was certainly not lost on continually oppressed Afri- can Americans. African American newspapers ran far fewer advertisements for the Statue’s pedestal, refusing to support a symbol of liberty when they could not at- tain that ideal. The New York Freeman for example ran no advertisements concerning the pedestal no matter how desperate the American Committee became.138 The Liberator spoke out adamantly against the Statue in 1883 writing, “The papers inform us that the statue of Liberty…now stands upon that structure completed… precisely because it is desirable that freedom should pervade this entire nation…it is undesirable, and of ill omen, that we should continue to make a parade of the name before coming into possession of the thing.” The article deemed the celebration of liberty in Ame- rica premature and spoke of America’s history writing, “One of the chief features of the American people – so prominent as to make us, deservedly, the laughing stock of other nations- has been a habit of boasting of our country as ‘the land of the free,” while it should have been called, “preeminently the land of the slave.” While others rejoiced about sectional reconciliation this ar- ticle declared, “We expect slavery will die. But powerful parties, aided by powerful circumstances, are laboring to restore and confirm it.”139 It went on to powerfully beg, “What we wish is that this nation might have pos- sessed moral and spiritual insight enough to recognize its present state, and virtue enough to refrain from ma- king new boasts on the score of freedom, until freedom is officially proclaimed throughout the land unto all in- habitants.” The author wanted the statue of Liberty to “remain unfinished until our transition state shall be over, until the last remnant of slavery shall be dead and buried,” because “An incomplete statue of Liberty accu- rately represents our present state.” This article encap- sulates the danger of the changing rhetoric surrounding the Statue because it demonstrates that Americans’ ce- lebration of liberty required actively turning a blind eye to the continued inequity African Americans faced.140 The Liberator called out Americans for funding a di- shonest symbol, using a fabricated national myth. The narrative of patriotism and reconciliation ul- timately won and the American Committee finally raised enough funds in 1886. On May 11th of that year, Grover Cleveland officially “authorized and directed to accept the colossal statue,” and promised that it would “be inaugurated with such ceremonies as will serve to testify the gratitude of our people,” to “the great nation which aided us in our struggle for freedom.”141 When Cleveland wrote these words he believed that the he had approved a Statue which celebrated the American Revolution. Joseph W. Drexel, a member of the Ameri- can Committee, had written to Cleveland on April 27th explaining the origins of the Statue: “You will doubtless remember that during the year 1875, when the people of the United States were making preparations for the celebration…of the hundredth anniversary of their national independence, the people of the Republic of France desired to give some token of their sympathy in the occasion.”142 Cleveland, convinced of this narrative and assured that newspapers had already raised most of the necessary funds, encouraged an elaborate inau- guration. Thus, Congress, which had vetoed several attempts to raise money for the pedestal, spared no ex- pense for the dedication; the estimated cost surpassed $106,000.143 This quick turnaround in the government’s opinion did not go unnoticed. The New York Tribune wrote that the dedication would take place “despite the indifference,” that the “Congress and the Administra- 12 THE STATUE OF LIBERTY

- 13. tion,” had shown prior.144 By the time crowds arrived to the Statue’s grand inauguration, the government and American Committee had completely commandeered the Statue’s narrative. People traveled in “from all sections of the country” to attend the Statue’s dedication.145 When the day ar- rived, it rained continuously but the spirit of the au- dience remained uplifted.146 The order of affairs during Inauguration day made much more sense for a natio- nalistic celebration of the American Revolution, rather than a day in memory of the bloody Civil War that had divided the nation. For example, the agenda included a “grand military parade,” in which “all the states and territories…shall be represented.” The parade included members from across the United States, a reminder of the nation’s new unity.147 The Committee invited a nu- mber of soldiers and veterans to join the celebration, along with the French delegation.148 One paper descri- bed how, “a general holiday appearance is presented by the moving bodies of soldiers militia, civic organiza- tions, and by the collection on the sidewalks of great crowds of people.”149 After the military parade, soldiers marched to the Battery, ships of war sailed to Bedloe’s Island, and the people of America gave a national sa- lute.150 Soldiers and civilians alike had to apply to be part of the parade, an exclusive event that consciously portrayed a singular story of American reunion and pa- triotism.151 The ceremony also reinforced the Centennial un- derstandingoftheStatueofLiberty.Thosecamewatched “French and American flags…flying from house-tops and windows in every direction.” 152 The day served as a celebration of America’s friendship to France that ori- ginated during the American Revolution. In fact, even the invitations for the inauguration emphasized the alliance of America and France. It included the inter- secting crests of both nations, making no reference to emancipation or the chains that remained by the Sta- tue’s feet.153 More than the decorations or the agenda though, the speeches given on dedication day shaped the audiences’ understanding of the Statue of Liberty. The government and the American Committee 13 The invitation for the Statue of Liberty dedication. Inauguration of the Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1887), 2. YALE HISTORICAL REVIEW

- 14. purposefully chose who spoke during the ceremony. One important figure who never received the chance to speak at the dedication included Bartholdi, the archi- tect of the masterpiece himself. The Cleveland Gazette, an African American newspaper, served as one of many newspapers which pointed out that “there were loud cries for Bartholdi” to talk during the ceremony and the audience “insisted upon a speech from the sculptor.” And yet, after Bartholdi “bowed and waved his hat,” General Schofield “abruptly cried out ‘Mr. Bartholdi has nothing to say.’”154 One cannot help but consider what the audience would have heard if the Committee had given Bartholdi the chance to speak up. There is no evidence that he would have corrected the historical memory of his Statue but the chance remains. Samuel Miller Hagerman, a poet, also found him- self silenced on the day of the dedication. He had prepared a poem for the inaugural ceremony and the American Committee admitted that, “the literary me- rits of the poem have been gratifyingly confirmed by three of America’s greatest poets.” And yet they went on, “It has been a source of the deepest regret that in the view of the…extreme length of the programme,” they claimed they had no choice but to “omit it from the programme.”155 In Hagerman’s poem “Liberty,” he opens by describing the Statues “Bursting her fetters,” immediately drawing attention to the chains on her feet that so many overlooked.156 He spoke openly about the Statue’s original intent to symbolize and celebrate emancipation writing, “Thou art as one from out the heavens, whom God himself hath sent, to seal forever Slavery’s tomb as Freedom’s monument.” 157 After so many had claimed the Statue for their own purposes, he returned agency to the monument, including a section of the poem where Lady Liberty herself speaks and de- clares, “Shut up within the darkened soul, there yearned since time began the light of that immortal truth – the liberty of man; through the long, tortuous labyrinth of ignorance and doubt, the slow procession of the past is winding dimly out.”158 The poem acknowledges the long arduous process it took to end slavery and more importantly, that the process had not completely ended. She continues, Freedom for men to use their powers by right of Nature’s rules, the laws that hold the world in leash, the laws that set men free; for, save through knowledge of her laws, there is no liberty. Freedom for every li- ving man, that stands upon the early, for all that can he black or white belongs to him by birth…Freedom from party prejudice from threat of craft…freedom for every man to vote, for every man to build, every man to own himself, to act his manhood out.159 Hagerman acknowledges many truths in his poem that others left out. He explicitly mentions that slave- ry ran across the lines of race. He acknowledges that save for certain laws, many would still own slaves. He calls attention to the party prejudice that persisted and the ways in which black suffrage had come under the “threat of craft.” Given these controversial, powerful lines, it should not come as a surprise that Hagerman’s poem did not make it on the dedication’s agenda. It is equally important to examine who did receive the chance to speak and what they took the opportunity to say. The French diplomat Ferdinand De Lesseps be- gan by exclaiming, “Great beacon rising from the waves at the threshold of free America…you have achieved the progress of your hundred years.” With that simple sentence he proclaimed the fight for equality over. He went on to discuss how the French “crossed the Atlan- tic a century ago” to help bring about independence, buying into the narrative that the Statue had always been meant for the Centennial.160 Senator Evarts spoke next, presenting the Statue in the name of the American Committee. Evarts mentioned the “the conflict which agitated and divided the people,” vaguely referring to the Civil War. He spoke of how “the liberty loving people of France felt an intense and solicitous interest,” without admitting that most of the French supported the Confederacy. He then celebrated how the Govern- ment, “made all its people equal and free,” denying the current reality for African Americans. Despite the revi- sionist history and reconciliation language, his speech perhaps served as one of the best chances for people to learn that the Statue related to the Civil War. And yet, most of the audience did not even hear him because, as several newspapers reported, the rain and tugboat whistles drowned him out.161,162 After he spoke, the Committee unveiled the Statue’s face, sacrificing Lady Liberty to the masses without a proper introduction. When the French flag fell, revealing the Statue, one re- porter recorded that “A hundred fourths of July broke loose,” further emphasizing that Lady Liberty would always remain misunderstood.163 President Cleveland, despite continuously vetoing 14 THE STATUE OF LIBERTY

- 15. funds for the Statue, received the opportunity to speak next. He clarified that, “We are not here today to bow be- fore the representation of a fierce and warlike god, willed with wrath and vengeance, but we joyously contemplate instead our own deity keeping watch and ward before the open gates of America…Instead of grasping in her hand thunderbolts of terror and of death, she holds aloft the light which illuminates the way to man’s enfranchi- sement.”164 He seemed to address and reject Bartholdi’s original, more violent designs and ideas. He wanted to ensure that people did not react to the embodiment of liberty by fighting for true freedom. Instead, he wanted the audience to believe that all Americans had already attainted liberty and that the monument now served to help the rest of the world. Cleveland’s speech remained vague and he did not allude to the American Revolu- tion or the Civil War, instead promoting a general in- terpretation of patriotism. A Lefaivre spoke next, in accord with Cleveland. He too declared that America had reached the “achievement of liberty,” and said, “the Republics of the past were debased by hostility toward foreigners by arbitrary and brutal power, and by slave- ry.”165 He acted as if America had overcome all forms of enslavement even though economic and fear tactics had created new cycles of debt and entrapment for African Americans. He then went on to tell a long story about Lafayette’s role in the American Revolution, spending the majority of the speech propagating the Centennial understanding of the statue.166 Again, neither of these speakers alluded to Laboulaye’s original intentions with Lady Liberty. General Schofield served as the last opportunity to remind people of the Statue’s original meaning. He too spoke of the American Revolution, the downfall of “dynastic purposes,” and the “Declaration of Indepen- dence.” Yet, before he did, he began by alluding to slave- ry and emancipation, discussing “Our great civil strife with all its expenditure and blood,” and claimed that “the development of liberty was impossible while she was shackled to the slave.” It seemed as though he mi- ght help the black man’s cause, until he began preaching about sectional reconciliation and denying the inequa- lity that persisted. He explained that bloodshed had been, “a terrible sacrifice for freedom,” and even said, “The results are so immeasurably great that by compa- rison the cost is insignificant.” He talked of how the “re- bel” had become a “patriotic citizen,” and claimed that the “enfranchisement of the individual” had been achie- ved. He said that all were “secure from fraud and the vo- ter from intimidation…and education furnished by the state for all liberty…and equal opportunity for honor and fortune the problems of labor and capital of social regeneration and moral growth of property and pover- ty will work themselves out under the benign influence of enlightened law making and law abiding liberty.”167 He, like many others, wanted Americans to believe that all disparity had disappeared and that Reconstruction had successfully come to a close. His use of the passive voice, when he declared that the “problems…will work themselves out,” reflects how the Republican Party took a step back at this time and left African Americans to fend for themselves. This day of supposed inclusivity and liberty, served only to emphasize the rampant inequality in America. The American Committee promised that “all organi- zations” could “make application” to join the inaugu- ration but its ultimate makeup in no way reflected the American public.168 “A multitude of people were as varied in their classes as were the vessels,” in the har- bor but those on Liberty Island itself constituted al- most solely white men.169 The Committee told women that they could not attend the dedication because they would get hurt and in the end only two attended.170 Those who watched from the water did not enjoy the ceremony nearly as much as those on the island. In fact, they could hardly see those on the boat next to them because of a heavy mist that day. For those who could see, “Umbrellas obscured for the most part,” the faces of those around them.171 To make matters worse, those on the ships only “occasionally,” saw “glimpses of the colos- sal statue.” Just as those in the harbor could not see the Statue, they could not attain full liberty, and especially full suffrage, by this moment.172 Despite what news- papers reported about a beautiful, seamless ceremony, feminist anarchists, socialist organizations, and ethnic minorities arrived on boats to protest the inauguration, a ceremony that in the end served only to highlight its own hypocrisy.173 African American newspapers used coverage of the ceremony as an opportunity to fight back against the rhetoric of reconciliation that the audience heard. By the 1880’s, when the Statue opened to the public, African Americans still faced marginalization in public places and at work.174 Thus, some African American papers ignored the Statue’s dedication entirely. Others in the black press debunked the romantic notions sur- 15YALE HISTORICAL REVIEW

- 16. rounding the Statue and explained that it certainly did not stand for their liberty.175,176 For example, the Cleve- land Gazette wrote, “Shove the Bartholdi statue, torch and all, into the ocean until the ‘liberty’ of this country is such as to make it possible for an inoffensive and in- dustrious colored man in the South to earn a respec- table living for himself and his family, without being ku-kluxed, perhaps murdered, his daughter and wife outraged, and his property destroyed.”177 This newspa- per expressed what all the white men on their podium had attempted to cover up, that liberty did not exist yet in America. The Cleveland Gazette also ran an editorial titled, “Postponing Bartholdi’s statue until there is liber- ty for colored as well.”178 These articles had many sen- timents similar to those which The Liberator expressed earlier. African Americans called out the Statue, which had the intentions of celebrating emancipation, for ce- lebrating liberation prematurely. W.E.B. Du Bois served as another prominent voice that rejected the Statue as a symbol of his liberty. In his autobiography, he described seeing the statue when he got back from Europe writing, “After a week we began to become tired and uneasy…At last it loomed on the morning when we saw the Statue of Liberty. I know not what multitude of emotions surged in the others, but I had to recall that mischievous little French girl whose eyes twinkled as she said, ‘Oh yes the Statue of Liber- ty! With its back toward America, and its face toward France.’”179 After these few sentences, he ends his chap- ter and does not refer to the Statue again. This short excerpt and the little girl’s quote that he includes elu- cidates how many felt about the Statue of Liberty. By accepting a definition of reconciliation and patriotism, it had turned its back on the many Americans who still needed it. The Statue may have been meant to enlighten the world but it first needed to enlighten the people of America, where racism and discrimination persisted. Bartholdi could never correct the narrative that had so overwhelmingly fallen from his grip, especially be- cause the Statue always needed more funding. As late as 1894, Congress passed an Act for the Statue’s mainte- nance, amounting to $64,000.180 That year, the Boston Investigator reported that “American are beginning to find…that France has made them a burdensome gift in sending Bartholdi’s famous statue,” and that “Inves- tigators claim that there are already alarming signs of dissolution in the statue.”181 In 1887, the Atchison Daily Champion wrote that “Bartholdi’s work has lost its freshness for all but a few strangers and enthusiasts.”182 The Statue would always need the American public on its side if it hoped to receive the funds it needed. It is no surprise then that meaning would change once again as immigration increased at the end of the nineteenth century. Americans only started to understand the Statue of Liberty as a symbol associated with immigration after the addition of the “New Colossus” and the construc- tion of Ellis Island. Emma Lazarus wrote the “New Co- lossus” in 1883 for a fundraiser for the pedestal, yet ano- ther ploy to fund the project. The poem began, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses year- ning to breathe free.”183 Lazarus, a wealth Manhattanite, had made Jewish refugees her newest cause and there- fore wrote a poem in the hope of America’s acceptance of them. Though many think of the Statue and poem as intertwined today, the public did not read her poem until 1903 when Lazarus’ friends convinced officials to engrave it on a plaque within the Statue’s pedestal.184 Those who arrived to America increasingly understood the Statue and its poem as a sign that the United States, the land of the free, accepted all refugees. The construc- tion of Ellis Island, completed in 1892, two minutes away from the Statue of Liberty, only strengthened the perceived connection between immigration and the Statue. The Statue’s new status as the welcome sign to America for immigrants was as ironic as its role as a sign of liberty for all. While Americans congratulated themselves and praised the Statue, xenophobia and violence towards immigrants rose quickly at the end of the twentieth century.185 The Statue of Liberty would remain a hypocritical reminder of the disparity and perceived equality in the United States to many of its viewers into the twentieth century. In fact, Puck Magazine published an image of the Statue of Liberty on fire in 1908 to reflect the horrors that African Americans continued to experience.186 In 1883 the Liberator wrote, “When the war for freedom shall have closed in victory, then will be the proper time to rear the statue of Liberty as our national emblem.”187 Has the war come to a close yet? Many, including those writing for the 1619 Project would certainly say no. In an ongoing New York Times Magazine initiative, Nikole Hannah-Jones argues that that many contemporary American institutions continue to propagate the legacy of slavery.188 Thus, to this day, many view the Statue of 16 THE STATUE OF LIBERTY

- 17. 17YALE HISTORICAL REVIEW Liberty as a representation of the “highest ideals and deepest ironies of our history.”189 It has been called a “wonder of the world,” but also a “disgrace.”190 It has been commandeered as a way to celebrate uncontrover- sial memories when others have been too divisive. The message of the Statue of Liberty, America’s great triumph over its original sin of slavery, was lost in the economic and fundraising imperatives of the day. And yet, if one looks closely, Lady Liberty still stands mid step. Her robe flows, her knee bends, and back heel points up off the ground.191 America has often fallen far short of her ideals, but Lady Liberty’s potential remains unbound. 1 Robert Belot and Baiel Bermond, Bartholdi (Paris: Perrin, 2004), 246. 2 Vermont Watchman, October 3, 1883. 3 Leslie Allen, Liberty: The Statue and the American Dream (New York: Statue of Liberty – Ellis Island Foundation, 1985), 30. 4 Albert Boime, Hollow Icons: The Politics of Sculpture in 19th Century France (Kent: Kent State University Press, 1987), 113. 5 Willadene Price, Bartholdi and the Statue of Liberty (Chicago: Rand McNally & Company, 1959), 38. 6 The JBHE Foundation, “Making the Case for the African-Amer- ican Origins of the Statue of Liberty,” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no 27 (Spring 2000): 66. 7 Julia Jacobs, “New Statue of Liberty Museum Illuminates a For- gotten History,” New York Times, May 15, 2019. 8 Edward Berenson, The Statue of Liberty: A Transatlantic Story (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 1. 9 “The Statue of Liberty in New York,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, October 18, 1884. 10 Emma Lazarus, Emma Lazarus: Selected Poems and Other Writings (Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2002), 50. 11 Charles E. Mercer, Statue of Liberty (New York: Putnam, 1985), 38. 12 Yasmin Sabina Khan, Enlightening the World: The Creation of the Statue of Liberty (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010), 5. 13 Zachary Schwartz, “The Statue of Liberty Was Originally intended to Celebrate the End of American Slavery,” Vice, September 14, 2016. 14 Price, Bartholdi and the Statue of Liberty, 37. 15 Price, Bartholdi and the Statue of Liberty, 37. 16 Berenson, The Statue of Liberty, 9. 17 Mabel Patterson, Through the Years with Famous Authors (Good Press, 2019), 14. 18 Edouard Laboulaye, Why the North Cannot Accept of Separa- tion (New York, Charles B. Richardson, 1863), 4. 19 Francesca Lidia Viano, Sentinel: The Unlikely Origins of the State of Liberty (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018), 204. 20 Viano, Sentinel, 111. 21 Viano, Sentinel, 227. 22 Price, Bartholdi and the Statue of Liberty, 37. 23 Charles River Editors, The Statue of Liberty: The History and Legacy of America’s Most Famous Statue, 2014, 68. 24 Laboulaye, Why the North Cannot Accept, 3. 25 Laboulaye, Why the North Cannot Accept,, 6-7. 26 Laboulaye, Why the North Cannot Accept,, 7. 27 Laboulaye, Why the North Cannot Accept,, 7. 28 Berenson, The Statue of Liberty, 9. 29 Laboulaye, Why the North Cannot Accept, 7. 30 Berenson, The Statue of Liberty, 9. 31 Jacobs, “New Statue of Liberty.” 32 Viano, Sentinel, 225. 33 Viano, Sentinel, 207. 34 “Abolition,” National Park Service, accessed March 18, 2020. Image from Puck Magazine, September 9, 1908. End Notes

- 18. 35 Berenson, The Statue of Liberty, 35. 36 Viano, Sentinel, 204. 37 Viano, Sentinel, 207. 38 Mary J. Shapiro, Gateway to Liberty: The Story of the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island (New York: Vintage Books, 1986), 12. 39 John Bigelow, Some Recollections of the Late Edouard Laboulaye (New York, 1888), 10. 40 Bigelow, Some Recollections, 2. 41 Bigelow, Some Recollections, 6. 42 Bigelow, Some Recollections, 3. 43 Bigelow, Some Recollections, 4. 44 Bigelow, Some Recollections, 4. 45 Bigelow, Some Recollections, 4. 46 The JBHE Foundation, “Making the Case for the African-Amer- ican Origins of the Statue of Liberty,” 66. 47 Bigelow, Some Recollections, 20. 48 Charles River Editors, The Statue of Liberty, 66. 49 Charles River Editors, The Statue of Liberty, 82. 50 Viano, Sentinel, 249. 51 Gillian Brockell, “The Statue of Liberty was Created to Celebrate Freed Slaves, not Immigrants, its New Museum Recounts,” The Washington Post, May 23rd, 2019. 52 Price, Bartholdi and The Statue of Liberty, 38. 53 The JBHE Foundation, “Making the Case for the African-Amer- ican Origins of the Statue of Liberty,” 66. 54 Michael Clodfelter, Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures. 1492-2015 (Jef- ferson: McFarland, 2017), 187. 55 Jean-Mari Schmitt, Bartholdi: A Certain Idea of Liberty (Stras- bourg: Nuée Bleue, 1985), 43-44. 56 Viano, Sentinel, 336. 57 Viano, Sentinel, 13. 58 Price, Bartholdi and The Statue of Liberty, 61. 59 Berenson, The Statue of Liberty, 12. 60 Berenson, The Statue of Liberty, 19. 61 Jacqueline Banerjee, “The Spirit of Freedom,” The Victorian Web. 62 Viano, Sentinel, 95. 63 Viano, Sentinel, 95. 64 The JBHE Foundation, “Making the Case for the African-Amer- ican Origins of the Statue of Liberty,” 65. 65 The JBHE Foundation, “Making the Case for the African-Amer- ican Origins of the Statue of Liberty, 65. 66 Lindsay Turley, “Myths Surrounding the Origin of the Statue of Liberty,” Museum of the City of New York, January 28, 2014. 67 Mercer, Statue of Liberty, 36. 68 “Abolition,” Breminate, April 18, 2019. 69 Jachos, "New Statue of Liberty." 70 Franz Kafka, Amerika (Munich: K, Wolff, 1927) in Adam Kirsch, “America, ‘Amerika,’” New York Times, January 2, 2009. 71 Berenson, The Statue of Liberty, 11. 72 Jacbos, “New Statue of Liberty.” 73 Price, Bartholdi and The Statue of Liberty, 64. 74 Mercer, Statue of Liberty, 54. 75 Mercer, Statue of Liberty, 37. 76 David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003), 6. 77 Blight, Race and Reunion, 6. 78 Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 570. 79 Foner, Reconstruction, 587. 80 William Eaton to David S. Reid, September 20, 1875, David S. Reid Papers, NCDAH in Foner, Reconstruction, 591. 81 Foner, Reconstruction, 590. 82 Foner, Reconstruction, 602. 83 Frank Barbour Coffin, “The Negro’s America,” Poems (Alexan- dria: Chadwyck-Healy Inc., 1994), 128. 84 Blight, Race and Reunion, 89. 85 Blight, Race and Reunion, 90. 86 Blight, Race and Reunion, 90. 87 Blight, Race and Reunion, 7. 88 Blight, Race and Reunion, 94. 89 Berenson, The Statue of Liberty, 30. 90 Berenson, The Statue of Liberty, 32. 91 Mercer, Statue of Liberty, 30. 92 Bartholdi to Laboulaye, April 30, 1872 in Shapiro, Gateway to Liberty, 14. 93 Allen, Liberty, 25. 94 Berenson, The Statue of Liberty, 34. 95 Charles River Editors, The Statue of Liberty, 25. 96 Charles River Editors, The Statue of Liberty, 415. 97 “The Statue of Liberty,” Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, September 29, 1876. 98 Mercer, Statue of Liberty, 70. 99 Charles River Editors, The Statue of Liberty, 26. 100 “France Gives the Statue of Liberty to the United States,” Histo- ry, accessed April 2, 2020. 101 Foner, Reconstruction, 564. 102 Foner, Reconstruction, 564. 103 Foner, Reconstruction, 569. 104 Foner, Reconstruction, 568. 105 “The Statue of Liberty,” Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, September 29, 1876. 106 “The Bartholdi Statue of Liberty,” Boston Daily Advertiser, De- cember 29, 1881. 107 “The Statue of Liberty,” Daily Evening Bulletin, December 7, 1882. 108 “Bartholdi’s Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World Has Ar- rived in the Harbor of New York, Liberty,” St. Louis Globe Democrat, May 19, 1883. 109 “Multiple Classified Advertisements,” Southwestern Christian Advocate, February 28th, 1884. 110 Megan Margino, “The Arm that Clutched the Torch: The Stat- ue of Liberty’s Campaign for a Pedestal,” New York Public Li- brary, April 7, 2015. 111 Mercer, Statue of Liberty, 56. 112 “The Statue of Liberty,” Daily Evening Bulletin, December 7, 1882. 113 The American Committee of the Statue of Liberty, An Appeal to the People of the United States in Behalf of the Great Statue in Mercer, Statue of Liberty, 36. 114 Mercer, Statue of Liberty, 37. 115 Mercer, Statue of Liberty, 38. 116 Arkansas Gazette, November 20, 1883. 117 The Grit, July 12, 1884. 118 Mercer, Statue of Liberty, 41. 18 THE STATUE OF LIBERTY

- 19. 119 “The Statue of Liberty,” North American, January 11, 1884. 120 Ibid. 121 Allen, Liberty, 30. 122 Mercer, Statue of Liberty, 49. 123 Mercer, Statue of Liberty, 73. 124 Mercer, Statue of Liberty, 73. 125 The World, May 14, 1883 in Mercer, Statue of Liberty 39. 126 Mercer, Statue of Liberty, 51. 127 Mercer, Statue of Liberty, 50. 128 Mercer, Statue of Liberty, 50. 129 Mercer, Statue of Liberty, 73. 130 “The Statue of Liberty,” Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, August 30, 1884. 131 Ibid. 132 “Multiple Classified Advertisements,” Southwestern Christian Advocate, February 28, 1884. 133 Rocky Mountain News, March 9, 1886. 134 The Congregationalist, May 7, 1885. 135 “The Bartholdi Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World,” July 4, 1885. 136 “Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World,” Committed on Foreign Affairs Discharged and Referred to the Committee on Appropriations, June 18, 1886. 137 Ibid. 138 John Bodnar, Laura Burt, Jennifer Stinson, and Barbara Trues- dell, “The Changing Face of the Statue of Liberty,” Center for the Study of History and Memory, Indiana University, De- cember 2005, 176. 139 “Shadow without Substance,” Liberator, December 11, 1883. 140 Ibid. 141 “Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World,” Message from the President of the United States, Relating to the Acceptance and Inauguration of the Colossal Statue of Liberty Enlight- ening the World, May 12, 1886. 142 Ibid. 143 Letter from Acting Secretary Treasury with Estimate from Secre- tary of State of Expense of Inaugurating the Statue of Liberty, United States Congress, May 29, 1886. 144 New York Tribune, October 8, 1886. 145 “The Statue of Liberty,” Rocky Mountain News, October 29, 1886. 146 “Unveiling the Statue of Liberty,” Idaho Avalanche, November 20, 1886. 147 Charles P. Stone, The Rocky Mountain News, October 18, 1886. 148 St. Louis Globe Democrat, October 26, 1886. 149 Stone, The Rocky Mountain News. 150 Inauguration of the State of Liberty Enlightening the World by the President of the United States (New York: Appleton and Company, 1887), 12. 151 Inauguration of the State of Liberty, 13. 152 Stone, The Rocky Mountain News. 153 Inauguration of the State of Liberty, 2. 154 “Enlightening the World,” Cleveland Gazette, October 30, 1886. 155 The Office of American Committee of Statue of Liberty, No- vember 6, 1886 in Samuel Miller Hagerman, Liberty as Deliv- ered by the Goddess at her Unveiling in the Harbor of New York (Brooklyn: Published by the Author, 1886), 5. 156 Hagerman, Liberty as Delivered by the Goddess, 9. 157 Hagerman, Liberty as Delivered by the Goddess, 14. 158 Hagerman, Liberty as Delivered by the Goddess, 15-17. 159 Hagerman, Liberty as Delivered by the Goddess, 21-22. 160 “Unveiling the Statue of Liberty,” Idaho Avalanche, November 20, 1886. 161 Inauguration of the State of Liberty, 27. 162 Allen, Liberty, 30. 163 Allen, Liberty, 30. 164 Inauguration of the State of Liberty, 32. 165 Inauguration of the State of Liberty, 35. 166 Inauguration of the State of Liberty, 39. 167 Unveiling the Statue of Liberty,” Idaho Avalanche, November 20, 1886. 168 Stone, The Rocky Mountain News, October 18, 1886. 169 “Unveiling the Statue of Liberty,” Idaho Avalanche, November 20, 1886. 170 Mercer, Statue of Liberty, 40. 171 “Unveiling the Statue of Liberty,” Idaho Avalanche, November 20, 1886. 172 “Unveiling the Statue of Liberty,” Idaho Avalanche, November 20, 1886. 173 Viano, Sentinel, 18. 174 Viano, Sentinel, 18. 175 “Abolition,” National Park Service. 176 Bodnar, The Changing Face, 176. 177 Jacobs, “New Statue of Liberty Museum.” 178 Andrew Serratore, “The Americans who saw Lady Liberty as a False Idol of Broken Promises,” Smithsonian, May 28, 2019. 179 William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, The Autobiography of W.E.B. Du Bois: A Soliloquoy on Viewing My Life from the Last Decade of its First Century (Oxford: Oxford university Press, 2007), 114. 180 “Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World,” Letter from the Acting Secretary of the Treasury Relative to Using the Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World as a Beacon, February 14, 1894. 181 “The Statue of Liberty,” Boston Investigator, June 2, 1894. 182 “Statue of Liberty,” Atchison Daily Champion, October 23, 1887. 183 “Lady Liberty and Immigration,” The City of Reliquary Muse- um and Civic Organization, accessed April 16, 2020. 184 Robin Jacobson, “Welcoming Refugees: How the Statue of Lib- erty Became the ‘Mother of Exiles,’” Congregation Beth El. 185 Catherine Rampell, “America has Always been Hostiles to Im- migrants,” Washington Post, August 27, 2015. 186 “Abolition,” National Park Service. 187 “Shadow without Substance,” Liberator, December 11, 1883. 188 Nikole Hannah-Jones, “Our Democracy’s Founding Ideals Were False When They Were Written,” New York Times Mag- azine, August 14, 2019. 189 Jacobs, “New Statue of Liberty Museum.” 190 Wisconsin Labor Advocate, November 5, 1886. 191 Berenson, The Statue of Liberty, 40. 19YALE HISTORICAL REVIEW

- 20. BIBLIOGRAPHY “Abolition.” National Park Service, accessed March 18, 2020. Arkansas Gazette, November 20, 1883. “A History of Evolving Meaning in the Statue of Liber- ty.” Brewminate, April 18, 2019. Allen, Leslie. Liberty: The Statue and the American Dream. New York: Statue of Liberty – Ellis Island Foundation, 1985. Arthur, Chester A. “Papers Relating to the Foreign Re- lations of the United States.” December 1, 1884. Banerjee, Jacqueline. “The Spirit of Freedom.” The Vic- torian Web. “Bartholdi Statue of Liberty.” 48th Congress, 1st Session, vol. 2255. “Bartholdi’s Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World Has Arrived in the Harbor of New York, Liberty.” St. Louis Globe Democrat, May 19, 1883. “Bartholdi Statue of ‘Liberty Enlightening the World.’” 28th Congress, 1st Session, vol. 2171. Belot, Robert and Baiel Bermond. Bartholdi. Paris: Per- rin, 2004. Berenson, Edward. The Statue of Liberty: A Transatlan- tic Story. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012. Bigelow, John. Some Recollections of the Late Edouard Laboulaye. New York, 1888. Bodnar, John and Laura Burt, Jennifer Stinson, and Barbara Truesdell. “The Changing Face of the Sta- tue of Liberty.” Center for the Study of History and Memory, Indiana University, December 2005. Boime, Albert. Hollow Icons: The Politics of Sculpture in 19th Century France. Kent: Kent State University Press, 1987. Brockell, Gillian. “The Statue of Liberty was Created to Celebrate Freed Slaves, not Immigrants, its New Museum Recounts.” The Washington Post, May 23rd, 2019. Charles River Editors. The Statue of Liberty: The History and Legacy of America’s Most Famous Statue, 2014. Clodfelter, Michael. Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Fi- gures. 1492-2015. Jefferson: McFarland, 2017. Coffin, Frank Barbour. “The Negro’s America.” Poems. Alexandria: Chadwyck-Healy Inc., 1994. Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revo- lution. New York: Harper & Row, 1988. Eaton, William to David S. Reid. September 20, 1875. David S. Reid Papers, NCDAH. “Enlightening the World,” Cleveland Gazette, October 30, 1886. Hagerman, Samuel Miller. Liberty as Delivered by the Goddess at her Unveiling in the Harbor of New York. Brooklyn: Published by the Author, 1886. Hutchinson, E. P. “The Present Status of Our Immi- gration Laws and Policies.” The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 25, no. 2 (April 1947): 161-173. Inauguration of the State of Liberty Enlightening the World by the President of the United States. New York: Appleton and Company, 1887. Jacobs, Julia. “New Statue of Liberty Museum Illumi- nates a Forgotten History.” New York Times, May 15, 2019. Hannah-Jones, Nikole. “Our Democracy’s Founding Ideals Were False When They Were Written.” New York Times Magazine, August 14, 2019. Kafka, Franz. Amerika. Munich: K, Wolff, 1927. Kirsch, Adam. “America, ‘Amerika.’” New York Times, January 2, 2009. 20 THE STATUE OF LIBERTY