This document summarizes and critiques various theories about the identity and origins of the ancient Sherden people. The author argues that the Sherden likely emerged from northern Egypt's Delta region, rather than being foreign invaders or part of a larger Sea Peoples confederation as commonly believed. The paper reviews the evidence used to link the Sherden to places like Sardinia, the Aegean, and Syria. It aims to determine whether the Sherden had a distinct cultural identity or if their name was simply a label applied by Egyptians. Revealing the Sherden's identity could provide broader context about interconnectedness and interactions in the ancient Mediterranean world during the Late Bronze Age collapse.

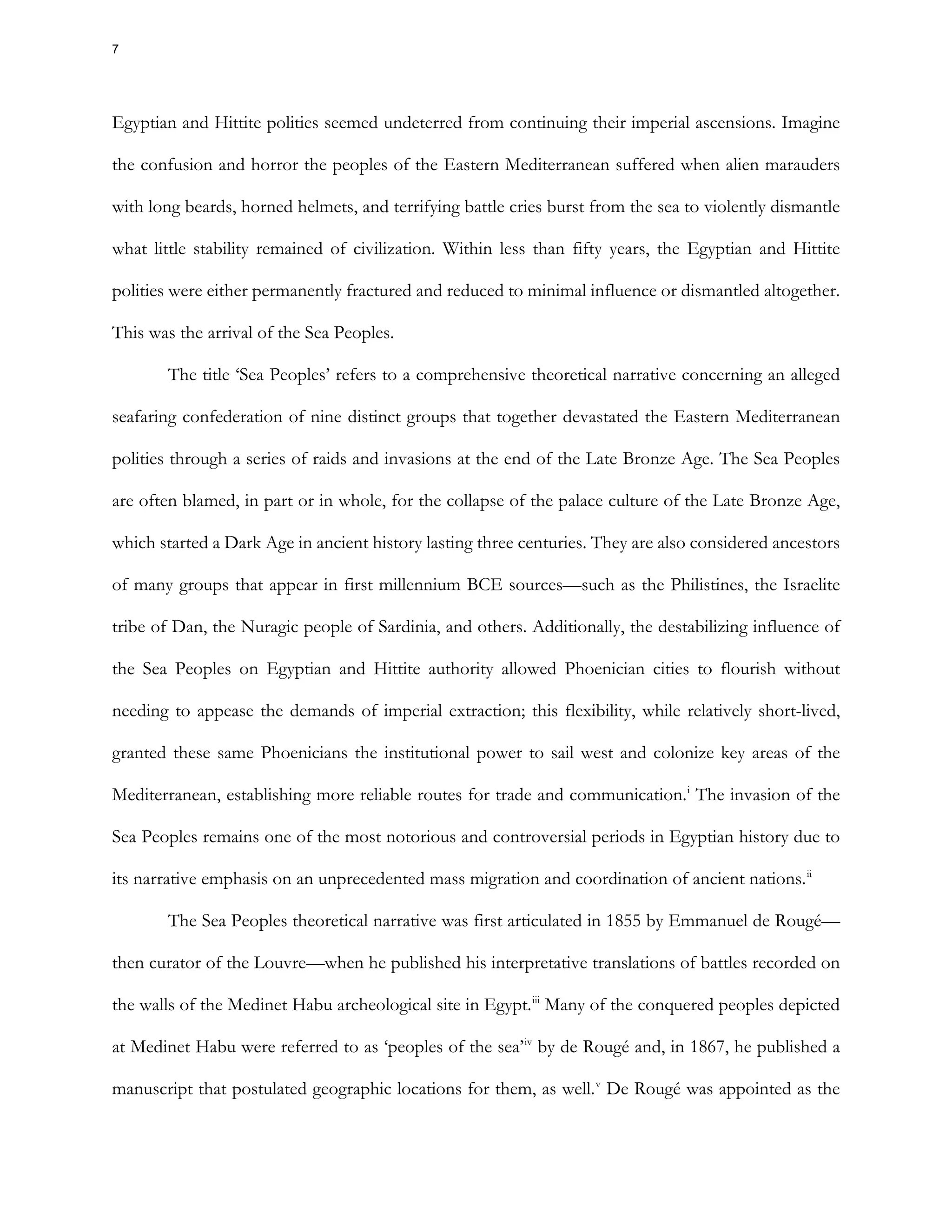

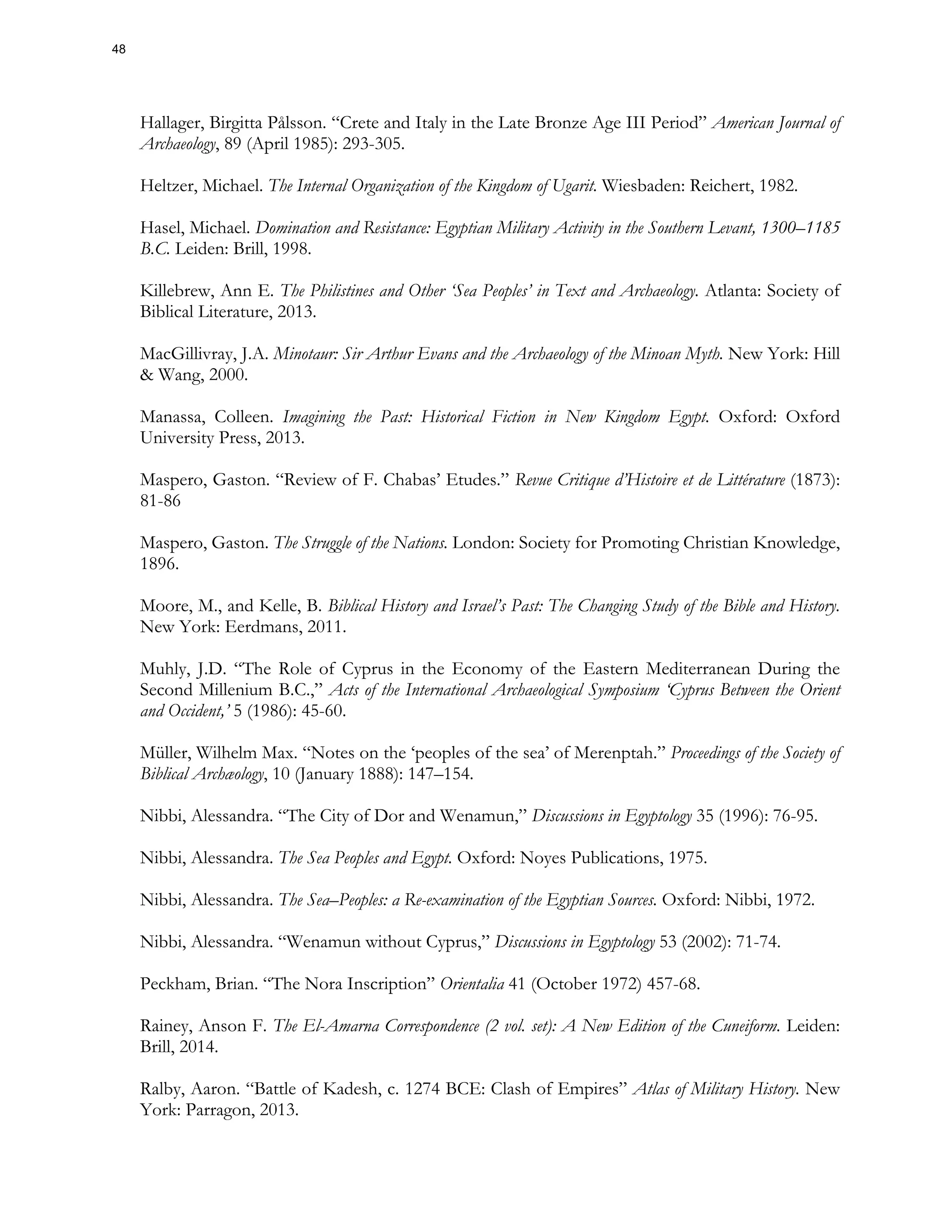

![Figure 1 (left): Wall relief from the Qadesh stela at the Ramesseum, Thebes. This likely represents a storming of an Amurru fortress

while on campaign.

Image and interpretation are from [Nancy K. Sandars, The Sea Peoples: Warriors of the Ancient Mediterranean 1250-1150 BC (London:

Thames & Hudson, 1978) 30].

Figure 2 (right): Wall relief in the Sun Temple of Abu Simbel in the south of Upper Egypt. This likely represents personal guards of

Ramesses II. These individuals are often interpreted as Sherden.

Image and interpretation are from [Henry Breasted, The Temples of Lower Nubia: Report of the Work of the Egyptian Expedition, Season of

1905-’06 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1906)c 2].

Considering the close timing of a Sherden defeat and subsequent imprisonment at the hands

of Ramesses II,xxii

it is likely that the captured Sherden soldiers present at the Battle of Qadesh are the

same Sherden captives who were hauled off to Egypt after losing to the Pharaoh two years earlier.

However, due to the irregular characteristics previously identified, not all of the visual depictions in

these wall reliefs should be assumed as sufficiently linked to the Sherden. Even if all of the individuals

depicted in the visual representations are Sherden, and even if they are sufficiently connected to

Sardinia, the argument would still depend on the assumption that the technology was developed in

Sardinia and only later transferred to the Eastern Mediterranean. While this hypothesis remains a

possibility, the antithesis is equally as plausible. The presence of rounded shields in the Eastern

Mediterranean at this time is therefore insufficient to justify assertions of Sherden as foreign

influencers.

Aside from etymological and visual interpretations, physical evidence has also served to

strengthen the resolve of Sardinia-Sherden proponents. The archeologist Roger Grosjean uncovered

statue menhirs on the island of Corsica depicting individuals that closely resemble the representations

of the alleged Sherden in Ramesses III’s Medinet Habu wall reliefs.xxiii

15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-15-2048.jpg)

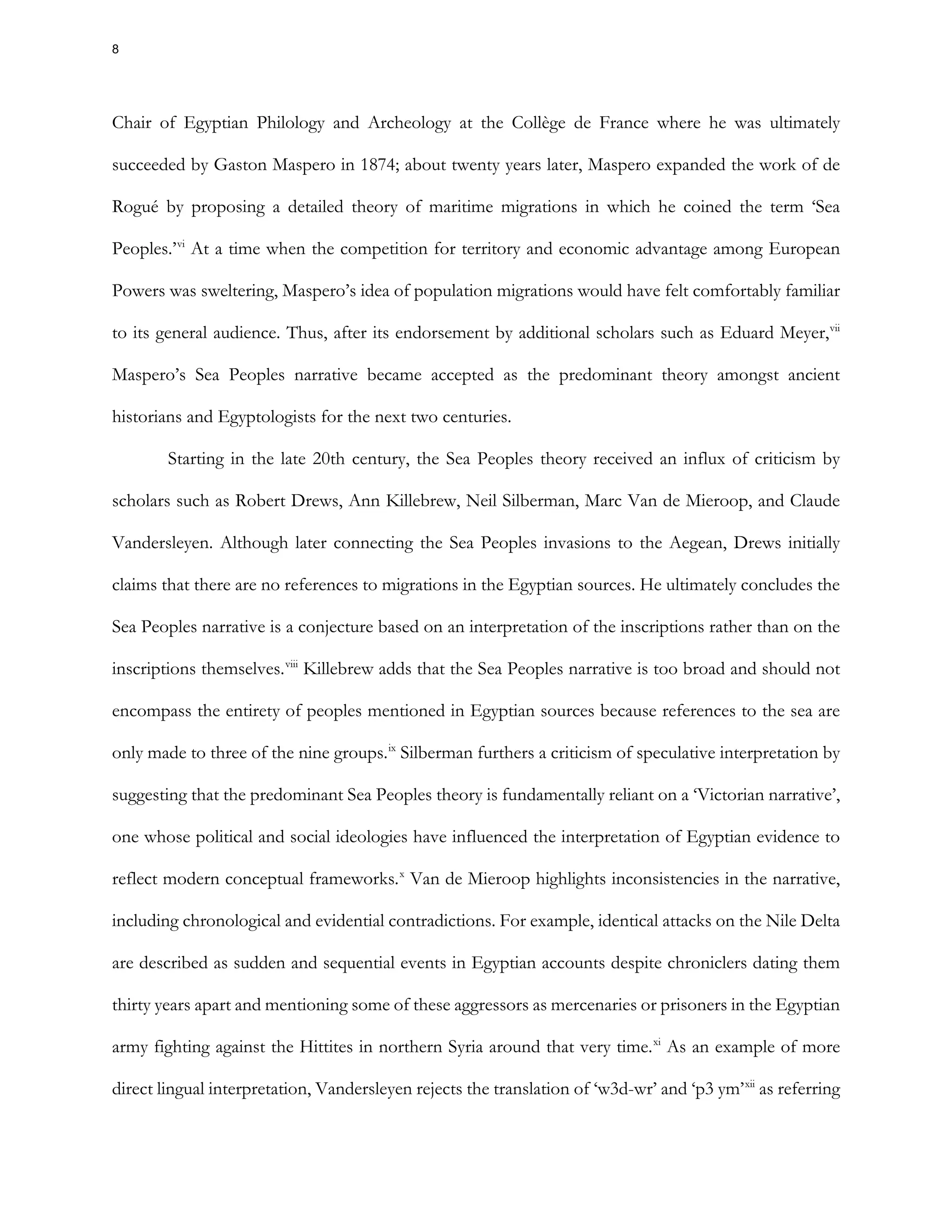

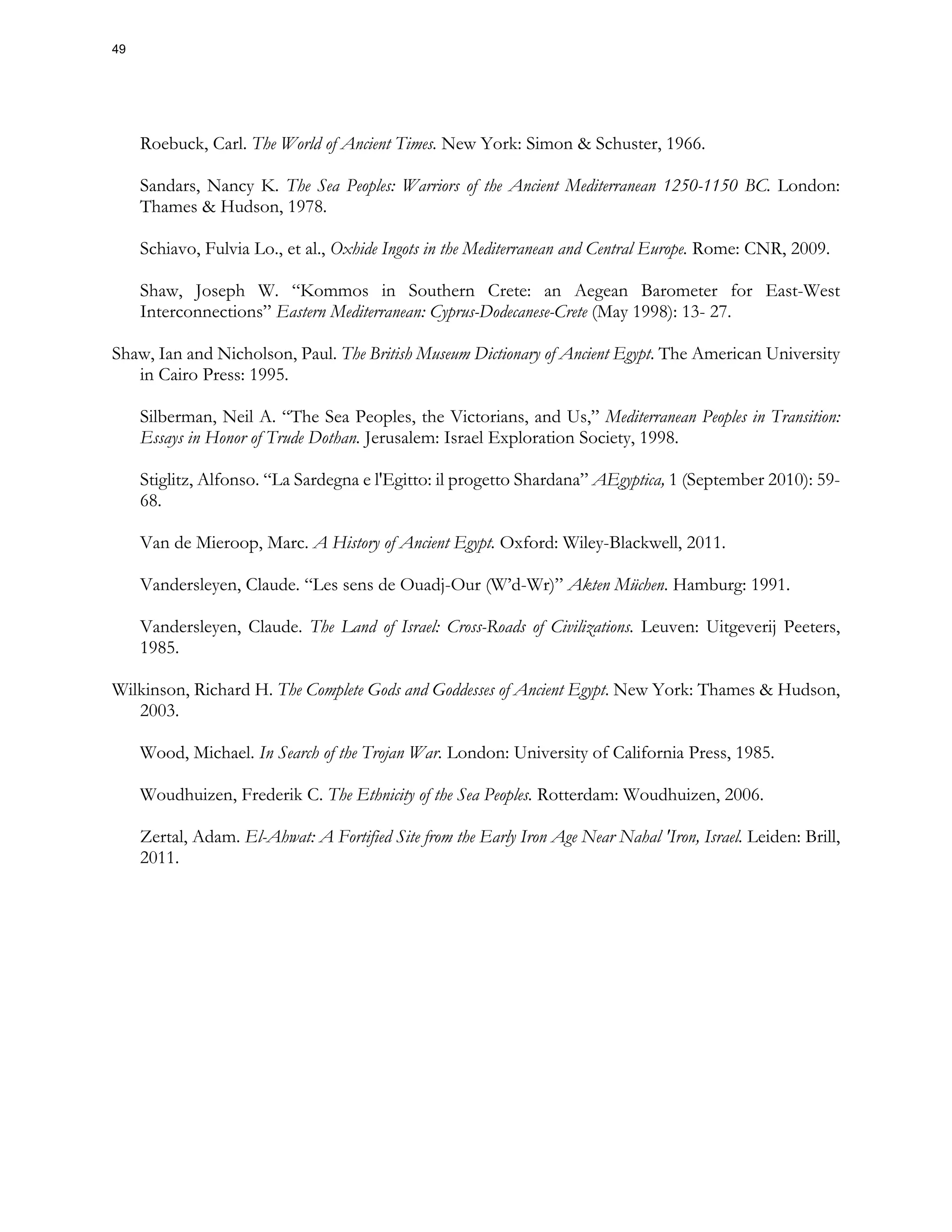

![Two archaeological sites, Cauria and Scalsa

Murta, were excavated in Corsica where

archaeologists uncovered statue-menhirs that

look eerily similar to the Sherden in the Medinet

Habu depictions; they date to between 1400 and

1000 BCE and are clearly militaristic.

The top image is from [Grosjean, 47]. The bottom image is from

[Nancy K. Sandars, The Sea Peoples: Warriors of the Ancient

Mediterranean 1250-1150 BC (London: Thames & Hudson, 1978),

103].

The existence of a network between Sardinia and the Eastern Mediterranean was suggested by the

archeologist Birgitta Hallager with her discovery of Mycenaean pottery—in the traditional style of the

Late Bronze Age—on the island of Sardinia.xxiv

A few years later, the academic Joseph Shaw uncovered

Sardinian pottery in southern Crete, indicating a reciprocal relationship between the two regions.xxv

The archeologist Margaret Guido corroborated these hypotheses with her discovery of oxhide ingots

inscribed with Cypro-Minoan markings found inside native Nuraghe establishments in Sardinia. She

then connected her findings to similar oxhide ingots previously discovered in Crete.xxvi

Guido also

suggested similarities between Egyptian visual representations of the Sherden and the Nuragic self-

depictions.

16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-16-2048.jpg)

![Above are three statue ingots created by the Nuragic peoples of Sardinia. The statue ingots show the Nuraghe with full combat-

readiness in a similar fashion to the Sherden. Note the similarities in horned helmets, short kilts, rounded shields, and swords to the

Egyptian representations.

[National Archeological Museum, Cagliari]—they are representative of depictions by Guido.

Furthermore, the archeologist Adam Zertal suggests that the El-Ahwat settlement in Canaan may be

evidence of a Sherden community in the region, in part due to architectural similarities to native

Nuraghe structures in Sardinia.xxvii

With regard to the Corsican statue menhirs, they lack sufficient similarities to the Medinet

Habu wall reliefs for a conclusive assertion that they depict the same individuals; there are major

differences between the two representations—such as the obvious size disparity in horn length and

the utilization of non-leather heavy armor. The existence of Mycenaean pottery in Sardinia and the

potentially Sardinian oxhide ingots in Crete certainly suggests some sort of connection between the

two regions. The absence of substantial quantities of Mycenaean pottery in Sardinia, however,

indicates a minor trade relationship at best, and surely not a mass migration or transfusion of

peoples.xxviii

In addition, the very origin of these oxhide ingots is disputed,xxix

and even if identified as

Sardinian, the small quantity does not prove an ongoing relationship between Crete and Sardinia—

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-17-2048.jpg)

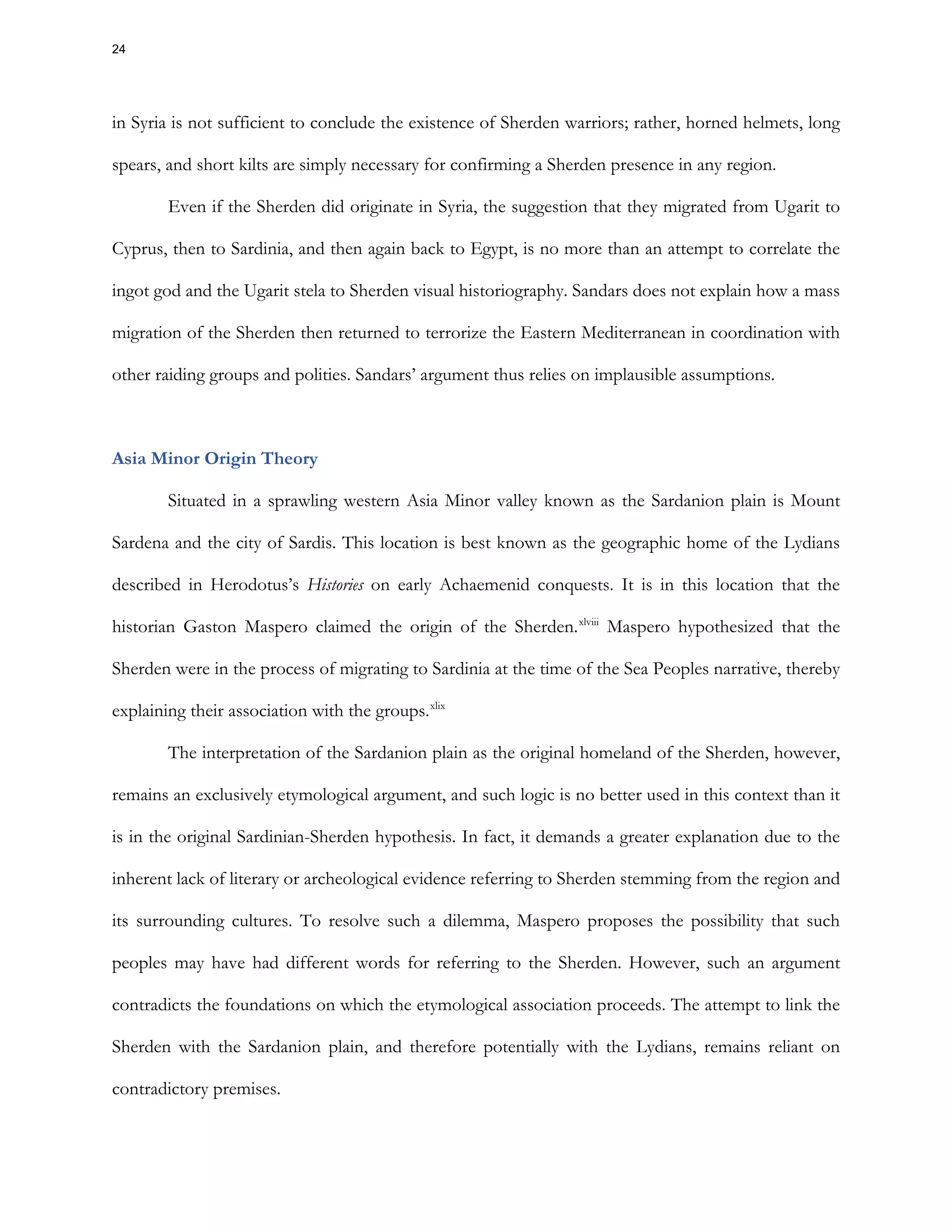

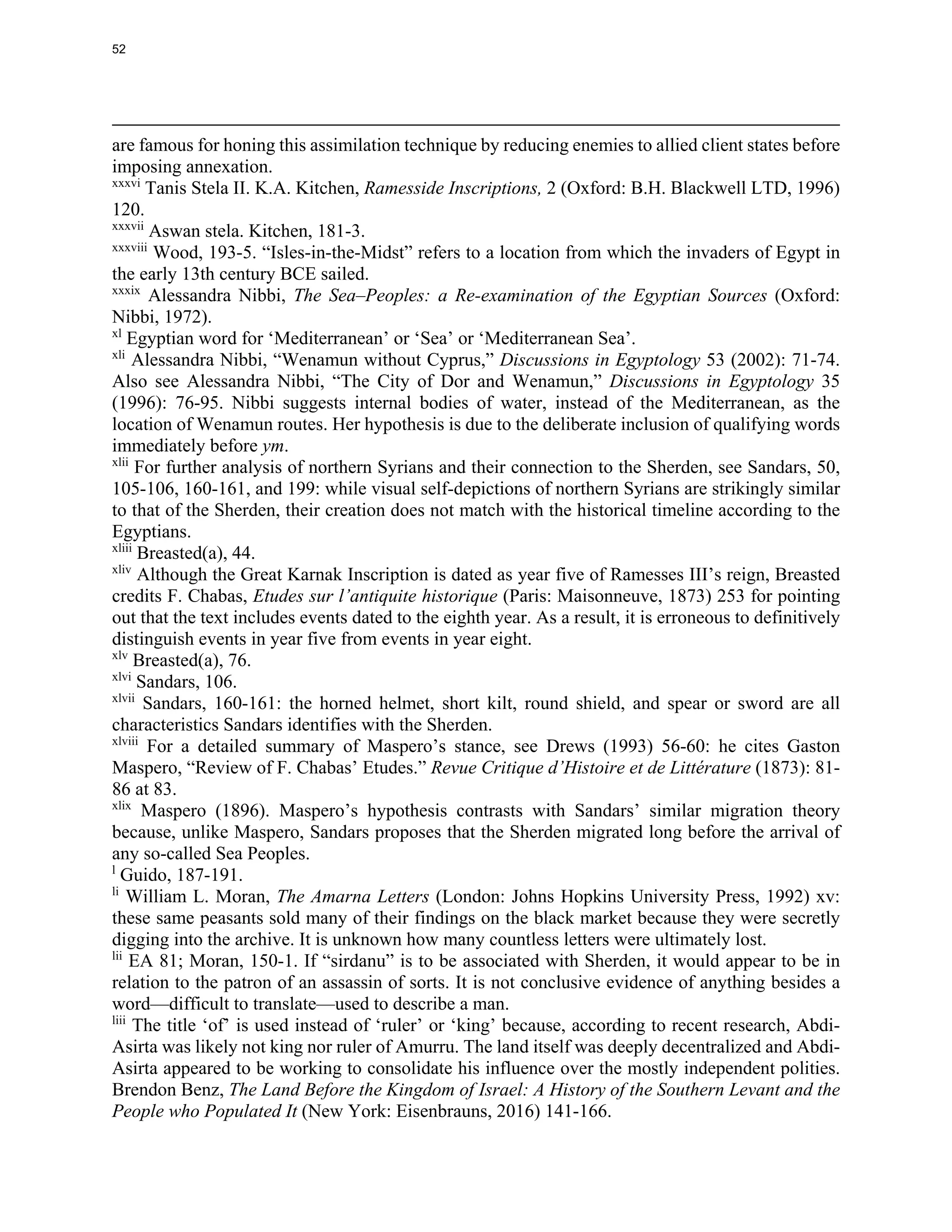

![century BCE; the archeologist Nancy Sandars claims that the Sherden homeland exists at the

northernmost extent of Egyptian influence in Syria.xlii

Sandars centers her argument on interpreting Egyptian depictions of Sherden at Medinet

Habu. The temple at Medinet Habu in Thebes uses visual renderings on wall reliefs often accompanied

by detailed inscriptions to honor the many victories of Ramesses III (1186-1155 BCE) against the Sea

Peoples and other engagements with the Libyans, as well as with the Hittites and their allies. A relief

on the outer side of the east wall of Medinet Habu describes a battle in the eighth year of Ramesses

III’s reign against “the northern countries,” and many of the aggressors were imprisoned once the

Egyptians achieved victory.xliii

Many Hittite and Mitanni chiefs as well as four groups commonly

associated with the Sea Peoples, including the Sherden, were among the captives.xliv

This relief offers

Sherden historiography its only definitive visual representation—one figure is explicitly labeled as

“Sherden of the sea.”xlv

Figure d is labeled as “Sherden of the Sea”

The image is from [Alessandra Nibbi, The Sea Peoples and Egypt (Oxford: Noyes Publications, 1975) plate 1].

This depiction includes a horned helmet with a raised sun-disk in the center as well as earrings and a

long beard to characterize the Sherden individual. This single captioned image of the Sherden

influenced subsequent evaluations and interpretations, all of which search for similar characteristics

in other visual representations.

21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-21-2048.jpg)

![Enkomi statue: [Cyprus Archaeological Museum, Nicosia]. Actual Ugarit stela depicting Baal: [Musée Du Louvre, Paris].

Sandars thereby proposes that the Sherden are indigenous to the northern Syria region; she

also theorizes that the Sherden left Ugarit following the city’s devastation in the 12th century BCE,

took refuge in Cyprus, and then migrated to Sardinia where they provided the island with its name.xlvii

Sandars’ northern Syrian hypothesis certainly highlights an array of previously ignored

evidence with regard to the identity of the Sherden. The apparent utilization of characteristics often

uniquely associated with the Sherden—horned helmets, long spears, and short kilts—by the peoples

of northern Syria indicates that the introduction of such technologies into the mainstream warfare of

the Eastern Mediterranean did not require a foreign cultural influence, as proponents of the Sardinian-

Sherden origin hypothesis frequently suggest. Nevertheless, the appearance of such characteristic attire

23](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-23-2048.jpg)

![Pihura sent Suteans; they killed Sirdanu-people, took 3 men, and brought them into

Egypt. If the king, my lord, does not send them [back], there is surely going to be a

revolt against me. If the king, my lord, loves his loyal servant, then send [back] the 3

men that I may live and guard the city for the king. And as to the king's writing, “Guard

yourself,” with what am I to guard? Send the 3 men whom Pihura brought in and then

I will survive: ‘Abdi-Ashirta, Yattin-Hadda, ‘Abdi-Milki. What are the sons of ‘Abdi-

Ashirta that they have taken the land of the king for themselves? May the king send

archers to take them.lv

This time, however, Rib-Hadda complains about a mercenary contingent of “Suteans” whom, he

claims, have slaughtered “sirdanu-people”lvi

and abducted three men while in Byblos. The “Suteans”

are noted several times throughout the Amarna letters, often grouped with other social classes such

as the ‘Apiru.lvii

The continual references to the threatening “Suteans” are likely no more than an

attempt by Rib-Hadda to invoke them as an enemy known to the Egyptians while simultaneously

incriminating Pahura—the Egyptian commissioner accused of the alleged crimes against Byblos. Rib-

Hadda warns of an impending revolt against Egyptian overlordship if the three seized men remain

unreturned. The three men are not detailed to the same extent as the “sirdanu-people” nor the

“Suteans” despite the negative impact of their forceful capture; it is therefore likely that the term

“sirdanu-people” further attests to their role as significant members of a societal administration

recognizable to the Pharaoh. The inclusion of murdered “sirdanu-people,” to stress the affronts

committed by these “Suteans,” indicates that the former class occupies a particularly significant and

symbolic role in the administration of Byblos’s local enforcement. It does not seem likely, given this

context, that “sirdanu” suggests a unique nationality foreign to the Pharaoh’s recognition.

With respect to the conclusions drawn from the Amarna letters, the term “sirdanu” likely

refers to a class of exceptionallviii

warriors often responsible for enforcing the codes of Byblos.

Moreover, as “sirdanu” is directly referenced by name in these letters sent to persuade Egyptian policy,

the crucial role that this class executes in supporting the kings of Byblos should be recognizable and

27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-27-2048.jpg)

![First, it is possible that Merenptah embarked on a quest to annex the entire Delta region of

Egypt during his reign. The invasions recounted by both of these sources are, in fact, a Libyan attempt

to aid the “northerners”lxix

“of the countries”lxx

from indefinitely falling to Egyptian authority. The

choice to detail the campaign as a foreign invasion legitimizes the Pharaoh’s imperialist war effort.

Second, Merenptah faced a Libyan invasion—supported by foreigners already at odds with

the Pharaoh—that instigated, or was instigated by, a Sherden revolt in one of the northern peripheries

of Egyptian influence. The result of the conflict was the defeat of the Libyan invasion and the slaughter

of Sherden.

In either scenario, the Sherden were northern Delta natives. In the events recounted by the

Great Karnak Inscription and the Athribis stela, however, the Sherden either faced an invasion or they

rose up in revolt against Egyptian hegemony. Even if the Sea Peoples narrative maintains some level

of credence, the Sherden should not be considered Sea Peoples themselves.

The presence of the Sherden in all source material disappears for the twenty years between

the reigns of Merenptah and Ramesses III (1186-1155 BCE). The Sherden then rapidly resurfaced

within inscriptions and reliefs at the Medinet Habu temple in Thebes. The Medinet Habu records

contain the only captioned depiction of Sherden—with horned helmets, long spears, and short kilts—

that subsequently provide Sherden historiography with a primary outline of how Sherden are visually

illustrated.

Aside from these visual markers, Medinet Habu contains additional reliefs and inscriptions

critical to the analysis of Sherden identity. One is a 75-line inscription on the inner west wall of the

second court that recounts an attack in the Nile Delta during the eighth year of Ramesses III’s reign:

The foreign countries made a conspiracy in their islands, All at once the lands were

removed and scattered in the fray. No land could stand before their arms: from Hatti,

Qode, Carchemish, Arzawa and Alashiya on, being cut off [i.e. destroyed] at one time.

A camp was set up in Amurru. They desolated its people, and its land was like that

which has never come into being. They were coming forward toward Egypt, while the

flame was prepared before them. Their confederation was the Peleset, Tjeker,

33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-33-2048.jpg)

![Shekelesh, Denyen and Weshesh, lands united. They laid their hands upon the land as

far as the circuit of the earth, their hearts confident and trusting: ‘Our plans will

succeed!’lxxi

The aggressors are described as “foreign countries” whose “confederation was the Peleset, Tjeker,

Shekelesh, Denyen, and Weshesh.” They obliterated Hittite forces and traditional local allies. While

two of the invaders explicitly named are associated with the Sea Peoples narrative, the Sherden are not

mentioned throughout the inscription. Nevertheless, an additional inscription on the interior of the

first court’s west wall describes a similar invasion of Egypt at this time and also serves as the basis for

the Sea Peoples narrative.

Inscription (excerpt): Thou puttest great terror of me in the hearts of their chiefs; the fear and dread of me before them; that I may

carry off their warriors (phrr), bound in my grasp, to lead them to thy ka, O my august father, – – – – –. Come, to [take] them, being:

Peleset (Pw-r'-s'-t), Denyen (D'-y-n-yw-n'), Shekelesh (S'-k-rw-s). Thy strength it was which was before me, overthrowing their seed,

– thy might, O lord of gods.

Inscription is from [Breasted(a), 48] and image is from [Epigraphic Survey(a), plate 44].

34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-34-2048.jpg)

![The visual representation accompanying the inscription depicts Ramesses III leading three

lines of captives to confront two Egyptian deities—Amon and Mut. The relief is accompanied by a

caption in the voice of Ramesses III where he pleads to Amon to “take them, being: Peleset, Denyen,

[and] Shekelesh.”lxxii

It is probable that Ramesses III’s three lines of prisoners in the visual

representation are analogous to the groups mentioned in its inscription. There are no key differences

between these three groups, except the bottom one displays hair darker than the other two. The kilts

worn by all of the prisoners, however, have a symmetrical cross-shape as well as three pieces of fabric

dangling from each. These kilts will appear once more in a later victory procession.

Visual representations of the Sherden also seem to appear in Medinet Habu wall reliefs. A land

army accompanying the invasion of the Delta was defeated by Ramesses III in the same year and,

aside from these engagements with the groups associated with the Sea Peoples, the Medinet Habu

reliefs recount conflicts with Libya and the Hittite sphere of influence. Within the visual depictions of

these battles, the iconic horned helmet with a raised sun-disk in between is clearly worn by numerous

supporters of the Egyptian cause. This visualization suggests that Egyptian sources deliberately sought

to convey the presence and support of Sherden warriors in these conflicts.

35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-35-2048.jpg)

![Gathered from multiple sites throughout Medinet Habu, the series of representations above depicts the Sherden as allies of the

Egyptians. A) The Sherden, one of whom is illustrated with a short beard, are shown in battle with the Sea Peoples; B) The Sherden

are depicted in conflict with the Libyan forces at odds with Egypt during the fifth and eleventh years of Ramesses III; C and D)

Sherden are shown fighting the Sea Peoples during the eighth year of Ramesses III; E) A large Sherden force is depicted storming a

Hittite fortress in Syria.

Image A is from [Epigraphic Survey(a), plate 34], B from [Ibid., plate 18], C from [Ibid., plate 34], D from [Ibid., plate 94], and E

from [Ibid., plate 39].

36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-36-2048.jpg)

![Note the group of individuals second from the top left.

The image is from [Epigraphic Survey(b), plate 62].

Of considerable interest is the second to top left representation of six soldiers—three of which are

shown in an identical fashion with matching spears, kilts, and horned helmets with raised sun-disks in

between. The other three figures—the two at the back of the line and the one leading the march—are

represented quite differently; they have short patterned kilts with dangling fabric, mismatching

headgear, and varying weaponry all dissimilar to the identical three. The former three soldiers are

Sherden infantry, alliedlxxix

to the Egyptians and marching in procession with the rest of Ramesses III’s

court. The wall relief’s visual representation of the Sherden is a unique depiction. First, it includes an

Egyptian blowing a horn toward the line—likely a drill instructor. Second, it renders a group that is

nonuniform in their individual characteristics: the latter two soldiers behind the Sherden support the

potential drill instructor, with one wielding a whip. These two visualizations point to a narrative of

39](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-39-2048.jpg)

![In July 1889, the United States government sent a commission to northwestern Minnesota to

counsel with the Ojibwe of the White Earth and Red Lake Reservations. The object of these visits

was straightforward: to negotiate the terms of the newly established Nelson Act, An act for the relief

and civilization of the Chippewa Indians in the State of Minnesota. The ambiguous title fails to convey its

insidious intentions. The commission was charged to “negotiate…for the complete cession and

relinquishment in writing of all [the Ojibwe’s] title and interest in and to all the reservations…except

the White Earth and Red Lake Reservations.” The lands of White Earth and Red Lake would “be

allotted…in severalty…in conformity with” the General Allotment Act of 1887, also known as the

Dawes Act. Any lands remaining after granting Ojibwe individual allotments would “be disposed of

by the United States to actual settlers only under the provisions of the homestead law.”lxxxix

Even

though the Ojibwe at White Earth and Red Lake retained the “privilege” of remaining on their

reservations, the Nelson Act powerfully advanced settler colonialism as the federal government

infiltrated Ojibwe territory.

The terms of the act met different degrees of success upon the two reservations. The White Earth

Ojibwe, after thorough negotiation, complied with the act. In the council minutes documenting the

commission’s meetings with members of White Earth, Chief Wob-on-ah-quod proclaimed, “If I was

a young man and had the advantages now thrown open to these young men…I should actually

overflow with joy.” Another elder, John Johnson, agreed to sign because of the opportunity “to

conquer poverty by our exertions” in assuming a sedentary, agricultural existence upon allotted

lands. Although some Ojibwe expressed concern that “there would hardly be enough land” for

everyone to receive his or her respective allotment, by the end of the meetings, the White Earth

Ojibwe agreed to the assimilatory project.lxxxix

The Red Lakers, in contrast, remained staunchly opposed to the act throughout their councils with

the commission. Statements such as “your mission here is a failure” and “we do not believe it is to

our interest to comply with [your] request” frequent the elders’ speech. The Red Lakers not only

expressed their resentment of the act, but they also succeeded in resisting some of its terms. Chief

May-dway-gon-on-ind dug in his heels, saying “I will never consent to the allotment plan. I wish to

lay out a reservation here where we can remain with our bands forever.”lxxxix

And indeed, the Red

Lake Ojibwe never consented to allotment, nor were they forced to. Red Lakers ceded almost three

million acres during the negotiations, but they continued to hold their unceded lands in common—

Red Lake remains one of the only reservations nationwide that successfully resisted allotment.lxxxix

56](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-56-2048.jpg)

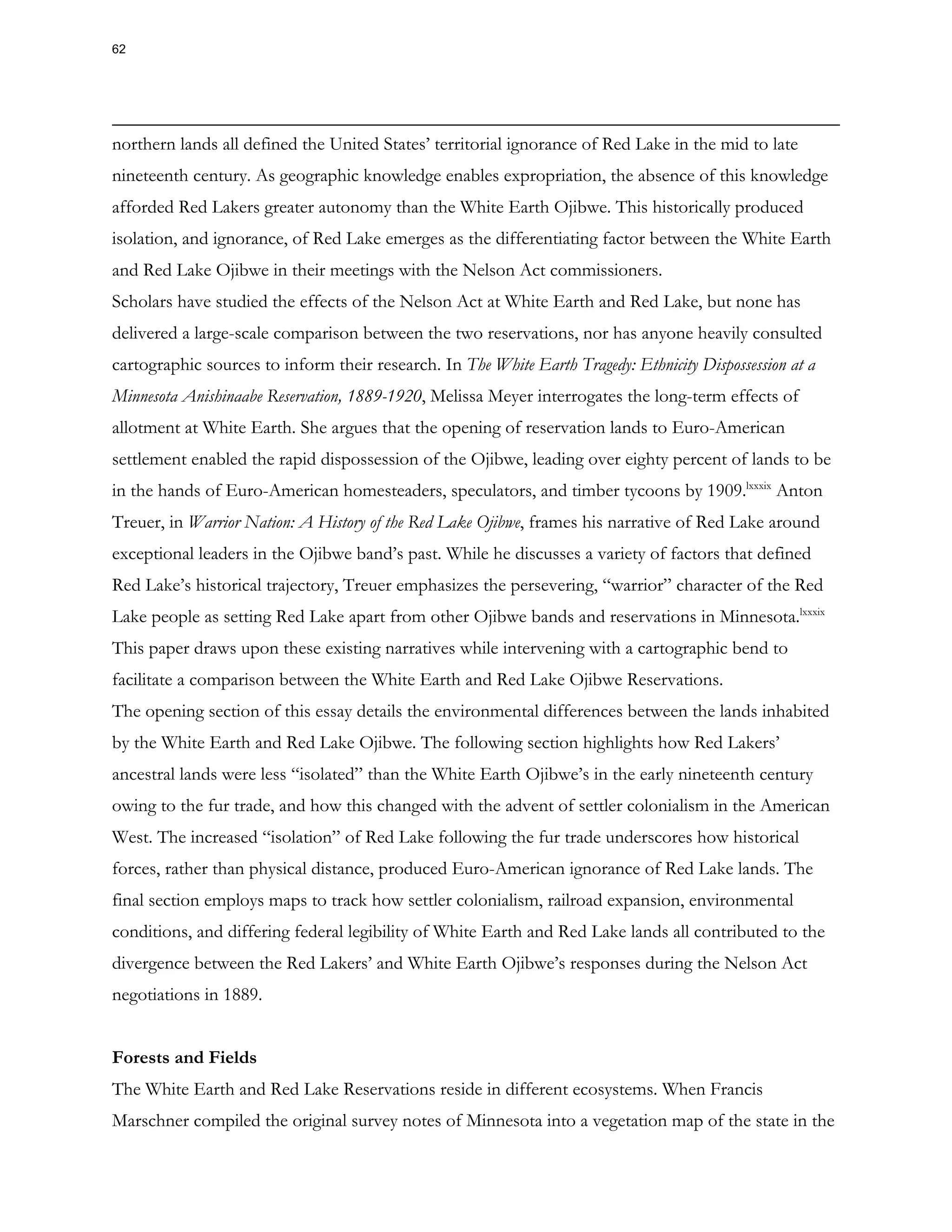

![Public Surveys in the State of Minnesota [map], 1:1,140,480 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. General Land Office,

1866).

Figure 2: This county atlas map, produced almost twenty years after the map in figure 1, shows how

public surveys encompassed the region south and west of Red Lake—called the Red River Valley—

but not Red Lake itself. The borders of White Earth and Red Lake have been enhanced by the

author. Notice, once again, how the trajectory of railroad lines (sprawling black lines) corresponds to

which lands were surveyed. Compared to Red Lake, the White Earth Reservation experiences close

encounters with railroad lines. Note how different the lakes at Red Lake appear on this map

compared to the map in 1866, highlighting the degree to which this region remained little known to

Euro-Americans. That the lands east of Red Lake also remained unsurveyed suggests they possessed

59](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-59-2048.jpg)

![similarities that made them unappealing to contemporary economic and settlement interests. Image

citation: H.R. Page & Co., Map of Minnesota [map], 1:1,260,000 (Chicago, IL: H.R. Page & Co., 1885).

Figure 3: This atlas map, from 1874, reiterates the themes of figures 1 and 2. The borders of White

Earth and Red Lake have been accentuated by the author. This map shows more clearly the process

by which the White Earth Reservation was surveyed: its northeastern portion was yet to be surveyed

in the mid-1870s. Considering how far north surveys had extended into the Red River Valley (far

western portion of Minnesota), the more gradual survey process at White Earth and other northern

regions in the state suggests the lands held less interest for Euro-Americans. The representation of

tree cover surrounding Red Lake and extending east reveals the Euro-Americans’ expectations for

what comprised these northern lands, even though they had not been surveyed. Image citation: A.T.

Andreas, Map of Northern Minnesota, 1874 [map], 1:760,320 (Chicago, IL: A.T. Andreas, 1874).

60](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-60-2048.jpg)

![Figure 4: This GLO map from 1878 sheds light on the same trends and themes introduced in the

first three figures. This map clearly shows the locations and sizes of Red Lake and White Earth.

Image citation: U.S. General Land Office, Map 8 – Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan [map], 1:1,267,200

(New York: Julius Bien, 1878).

When viewing figures 1–4, it is tempting to explain the differences between White Earth and Red

Lake’s legibility in terms of geographic isolation. In the far north of Minnesota, Red Lake lay out of

easy grasp of Euro-American settlers, so this seems a reasonable assumption. White Earth was first

surveyed in the 1870s; Red Lake not until the 1890s.lxxxix

In fact, one of the Nelson Act

commissioners told the Red Lakers that “it would be impossible to make the individual allotments”

for their reservation in the same manner as for White Earth, as “your reservation has not been

surveyed.”lxxxix

But the concept of “isolation” itself requires explanation. Isolation is historically

produced and malleable, and it has as much to do with the broader logic of settler colonialism as it

does with physical distance. How did Red Lake become isolated, while White Earth became legible

and appropriable? What factors were involved in producing this isolation?

Reading the GLO and county atlas maps alongside other historical sources exposes the converging

factors that resulted in Red Lake’s perceived isolation. The environmental differences between

White Earth and Red Lake, the varying political situations of the Ojibwe bands (at the two

reservations), and the evolving Euro-American interests in the economic potential of Minnesota’s

61](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-61-2048.jpg)

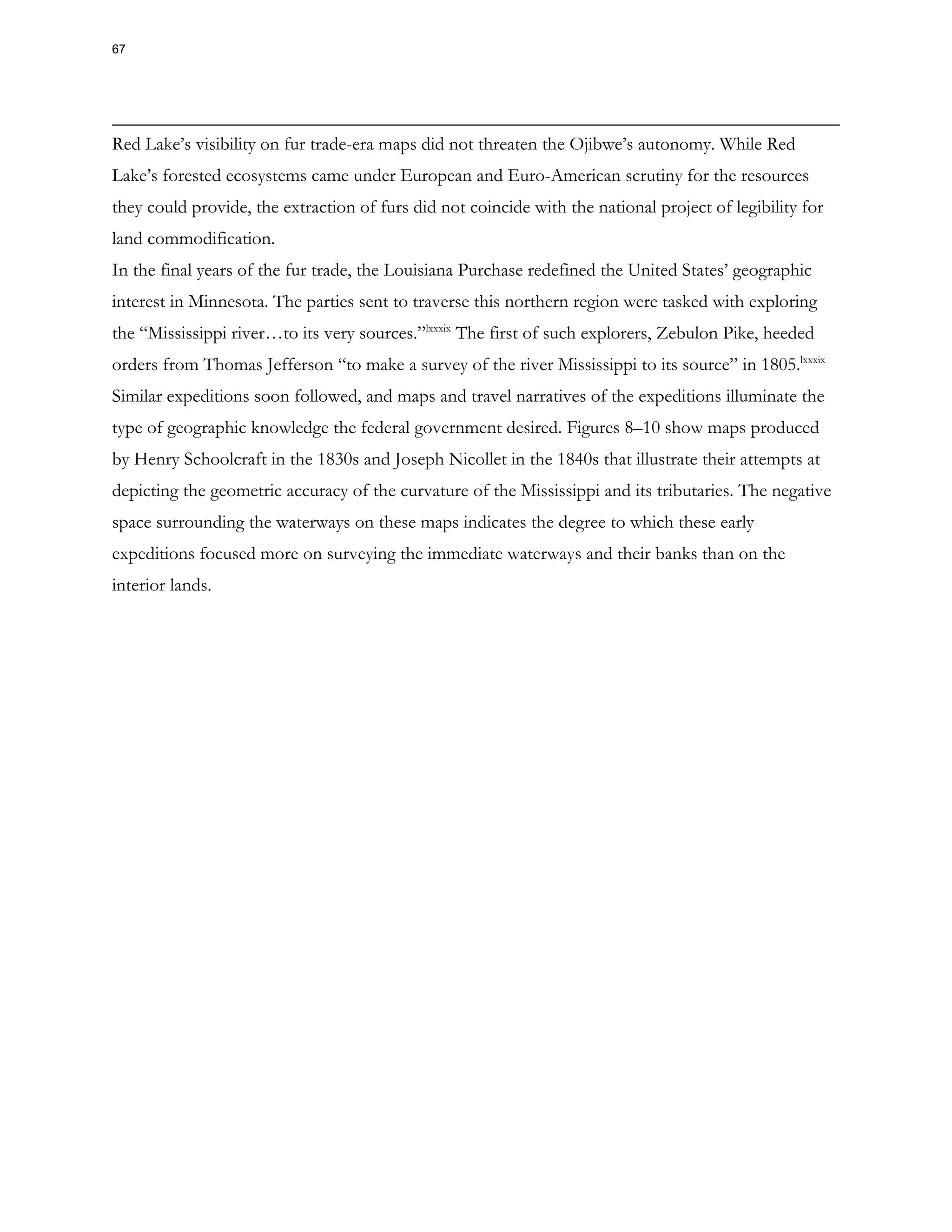

![Figure 5: This zoomed-in view of the Marschner map shows the different environmental conditions

at White Earth and Red Lake. The bright green lines, applied by the author, delimit the visible

sections of White Earth and Red Lake. The lower left corner of the image shows White Earth,

encompassing terrain represented in yellows, reds, greens, and blues. Red Lake largely occupies

territory of greys, pinks, and blues. The yellow inside Red Lake borders is generally confined to the

west of the lakes. Yellows represent grasslands; reds and greens hardwood forests; and greys, pinks,

and blues coniferous ecosystems. Image citation: F.J. Marschner, The Original Vegetation Map of

Minnesota [map], 1:500,000 (St. Paul, MN: North Central Forest Experiment Station, Forest Service,

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, 1930). This is a 1974 colored version of the 1930 original.

Figure 6: The Marschner map assists in understanding which lands were of interest to Euro-

Americans in the mid nineteenth century. The locations of White Earth and Red Lake have been

64](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-64-2048.jpg)

![applied to this map by the author. White Earth is shown on the map as a gray square southwest of

the larger Red Lake Reservation. The yellows represent the grasslands—which would yield

agricultural harvests—and these lands extended to the Red River Valley west of Red Lake.

Minnesota’s far northern forests did not become of great interest to Euro-Americans until

lumbering intensified in the late nineteenth century. Reading this map alongside railroad maps and

land surveys of Minnesota explains how environmental conditions contributed to the different

experiences of the Ojibwe at White Earth and Red Lake. Image citation: F.J. Marschner, The Original

Vegetation Map of Minnesota [map], 1:500,000 (St. Paul, MN: North Central Forest Experiment

Station, Forest Service, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, 1930). This is a 1974 colored version of the 1930

original.

Understanding the environmental differences between the two reservations lays the groundwork for

evaluating their differing visibility on federal maps. Not only do forests and fields create different

experiences in traversing the landscape, but they also hold more or less interest to Euro-Americans

depending on contemporary economic incentives. Tracing Ojibwe-Euro-American encounters and

their relationships to the land from the fur trade to the reservation era elucidates the role the

environment played in Red Lake’s evading the map.

1800s-1850s: The Fur Trade and Exploring the Mississippi “To Its Very Sources”

The map William Clark completed in 1810 (that hangs in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript

Library) shows Red Lake with detailed interest. Lewis and Clark never ventured as far north as

Minnesota, but Clark drew on existing geographical sources to fill in information about regions he

never visited. While geometrically inaccurate on Clark’s map, the lake is clearly labelled “Red Lake.”

When viewing figure 7, notice how a swarm of other words surround the lake: some indicate

latitudes, others list “NW Co.,” and others name lakes that form a chain leading southeast from Red

Lake. The presence of locations marked as “NW Co.”—representing the North West Company, a

fur trade company headquartered in Montreal—reveals the degree to which Euro-American

geographic knowledge of Red Lake in the period converged with fur trade interests.lxxxix

65](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-65-2048.jpg)

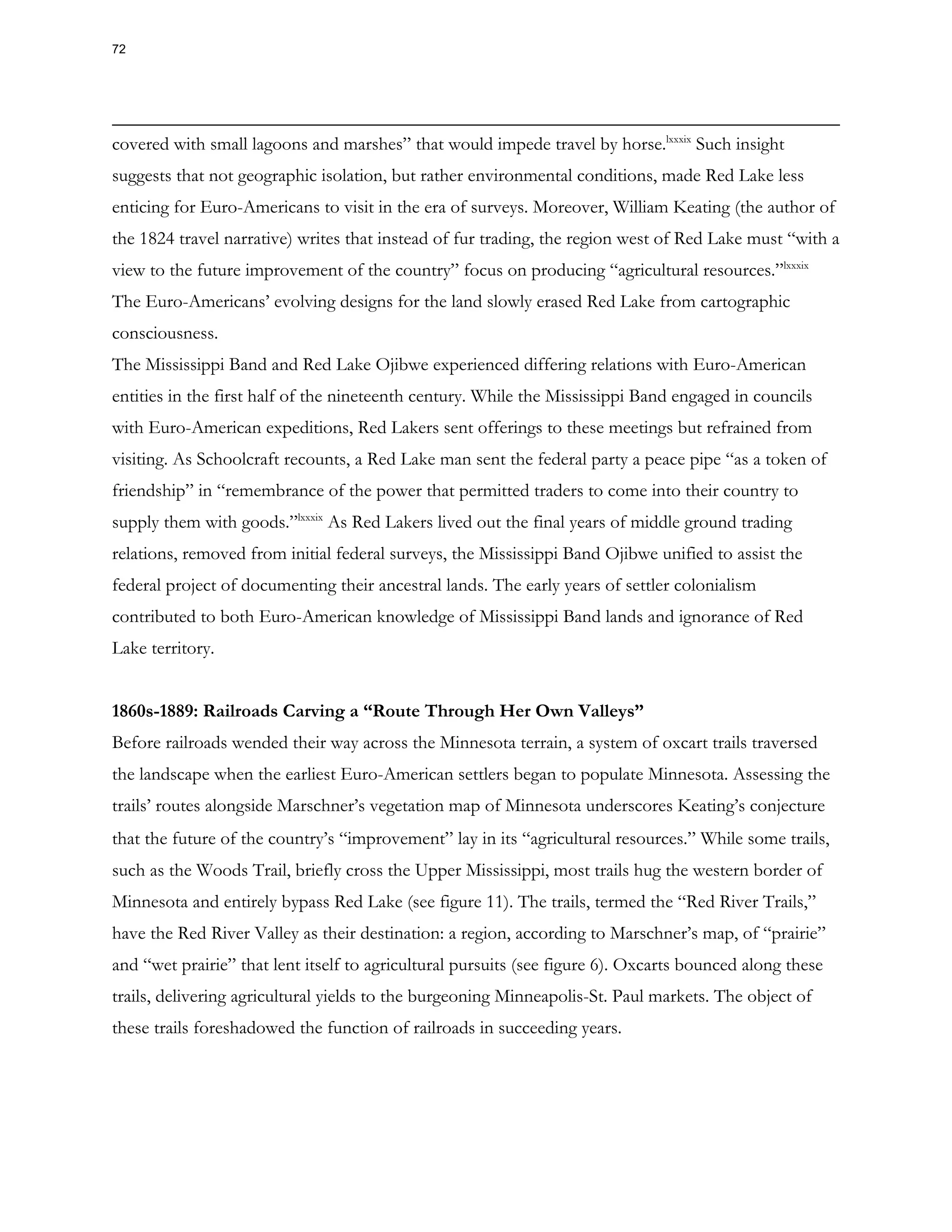

![Figure 7: This zoomed-in view of Clark’s 1810 map shows Red Lake and surrounding waterways.

The labels, such as “NW Co.,” indicate the fur trade knowledge that led to Red Lake’s appearance

on the map. Notice how the chain of lakes running southeast from Red Lake conveys the experience

of navigating the region (as opposed to surveying it for land commodification). Image citation:

William Clark, Clark’s Map of 1810 [map], no scale given, from Lewis and Clark Expedition Maps

and Receipt, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Euro-American geographic knowledge of Red Lake from the fur trade emerged from navigating the

land. Before the fur trade became economically extinct in the 1840s, the northern forests of

Minnesota abounded with trading posts where Ojibwe trappers exchanged furs for items such as

guns. Relations between early fur traders (especially of French origin) and the Ojibwe resulted in a

new ethnic group called the métis, or mixed bloods. The Ojibwe, métis, and European traders

coexisted in what Richard White terms the “middle ground.”lxxxix

The middle ground describes the

process by which Europeans and Ojibwe depended on each other for resources and survival, and

the geographic information that adorns European maps from this period grew out of these

partnerships.lxxxix

The chain of lakes on Clark’s map linking Red Lake to nearby lakes did not develop

from a settler colonial desire to survey the land. Rather, fur trade companies created maps to

navigate the waterways to manage the outposts that facilitated their economic success. In this way,

66](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-66-2048.jpg)

![Figure 8: This map, prepared by Henry Schoolcraft from his 1830s travels along the Mississippi

River, highlights the federal government’s interest in documenting the geometric accuracy of the

river and its surrounding waterways. On one of the peninsulas extending into Leech Lake,

Schoolcraft marks the presence of an Ojibwe village, thereby making the group visible in this early

survey of Western territory. Notice the absence of Red Lake from the map. Image citation: Henry R.

Schoolcraft, Sketch of the Sources of the Mississippi River [map], no scale given, in Narrative of an expedition

through the upper Mississippi to Itasca Lake (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1834).

68](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-68-2048.jpg)

![Figure 9: This close-up image of Joseph Nicollet’s survey of the Mississippi River region elucidates

the extensive geographic knowledge accumulated about the Upper Mississippi as opposed to Red

Lake (waterways not nearly as detailed at Red Lake). Nicollet labels the land at Red Lake as

“Chipeway Country”—the federal government used “Chippewa” to refer to the Ojibwe—while the

absence of this descriptor in the Upper Mississippi suggests this land lost its status as “Indian

country” during the early surveys. Image citation: J.N. Nicollet and J.C. Frémont, Map of the

hydrological basin of the Mississippi River [map], 1:600,000 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Congress, Senate,

1842).

In addition to maps, travel narratives convey the other types of knowledge collected. The War

Department “directed [Schoolcraft]” to record “all the statistical facts he [could] procure” about the

Indigenous peoples occupying the lands adjacent to the Mississippi River.lxxxix

Schoolcraft’s 1830s

expedition served as a surveillance mission to record the contemporary Ojibwe occupants of the

land. Upon closer inspection, figure 8 lists the precise location of an Ojibwe village near the

headwaters of the Mississippi River. The identity of the Ojibwe Schoolcraft encountered in this

region sheds light on their future dispossession: they are the Mississippi Band of Chippewa Indians,

the band that experienced a forced relocation to the White Earth Reservation in 1867.lxxxix

By

69](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-69-2048.jpg)

![marking them on his map in his “survey” of national territory, Schoolcraft initiated the project of

legibility that would enable their removal.

Schoolcraft not only documented the Ojibwe’s presence, but he also co-opted their geographic

knowledge. He hired them as guides, “request[ing] [them] to delineate maps of the country” and

asking them “to furnish the requisite number of hunting canoes and guides.”lxxxix

By guiding

Schoolcraft to Lake Itasca, where he “erect[ed] a flag staff” to claim the land for the United States,

the Mississippi Band Ojibwe became unwitting partners in their own dispossession.lxxxix

Other

contemporary maps, such as those prepared by Nicollet, feature Ojibwe place names alongside

English and French names (see figure 9). Although this may signify Nicollet’s respect for the

Indigenous inhabitants, the visibility of Ojibwe names nevertheless indicates their complicity in

working with the federal government to document the land.

Unlike the Mississippi Band Ojibwe, the Red Lakers lay outside the federal government’s immediate

geographic interest. Schoolcraft’s map in his 1834 narrative does not even show Red Lake. And

while Nicollet features Red Lake, the detail of the upper Mississippi River region does not carry over

to Red Lake or to the waterways surrounding the lake. Nicollet does note the “Indian Village” at

Red Lake, but the map gives the impression that the Red Lakers remain isolated. After all, on figure

9 “Chipeway Country” labels Red Lake, while the intricately depicted waterways of the Upper

Mississippi region no longer bear such an epithet. A different Schoolcraft map (created with “Lieut.

J. Allen” in 1832) recognizes Red Lake’s heritage as a fur trading hub by documenting a chain of

lakes reminiscent to what appears on Clark’s map and labeling it “Traders Route to R. Lake” (see

figure 10). These depictions highlight the degree to which Red Lake remained in the federal

government’s consciousness because of its historical fur trade prowess. Nevertheless, the dawning

era of Western settler colonialism led the federal government to favor the Mississippi River regions

instead of the forested lands of northern Minnesota.

70](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-70-2048.jpg)

![Figure 10: This Schoolcraft map shows Red Lake (upper left corner). Notice how its geometric

shape differs significantly from the portrayal on Clark’s map and Nicollet’s map. These geometric

inconsistencies indicate that Euro-American agents did not visit Red Lake to make precise survey

measurements. Schoolcraft instead uses a string of lakes to describe the “Traders route to R. Lake,”

recognizing the region’s value during the fur trade. Image citation: Henry R. Schoolcraft and J. Allen,

Map of the Route passed over by an Expedition into the Indian Country in 1832 to the Source of the Mississippi

[map], no scale given, in Schoolcraft and Allen—expedition to northwest Indians (Washington, D.C.: Gale &

Seaton, 1834).

A travel narrative from 1824 suggests that Red Lake posed challenges for travel that diminished

interest in visiting the region and its inhabitants in the early years of surveying. While Major Long,

who led the expedition discussed in the narrative, was “proposed to travel along the northern

boundary of the United States to Lake Superior,” local settlers informed him “that such an

undertaking would be impracticable; the whole country from Red Lake to…Lake Superior, being

71](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-71-2048.jpg)

![Figure 11: This map reconstructs the routes of the oxcart trails that preceded the earliest railroads in

Minnesota. When viewed alongside the Marschner map (figure 6), it is clear that the trails traverse

the grasslands that yielded agricultural produce. Notice how some of the trails cross lands near the

Mississippi Band Ojibwe’s homelands (along the Mississippi River near Crow Wing River and

Brainerd on this map). All trails steer clear of Red Lake. Image citation: Rhoda R. Gilman, Carolyn

Gilman, Deborah M. Stultz, Red River Trails [map], no scale given, in The Red River Trails: Oxcart

Routes Between St. Paul and the Selkirk Settlement, 1820-1870 (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society

Press, 1979).

73](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-73-2048.jpg)

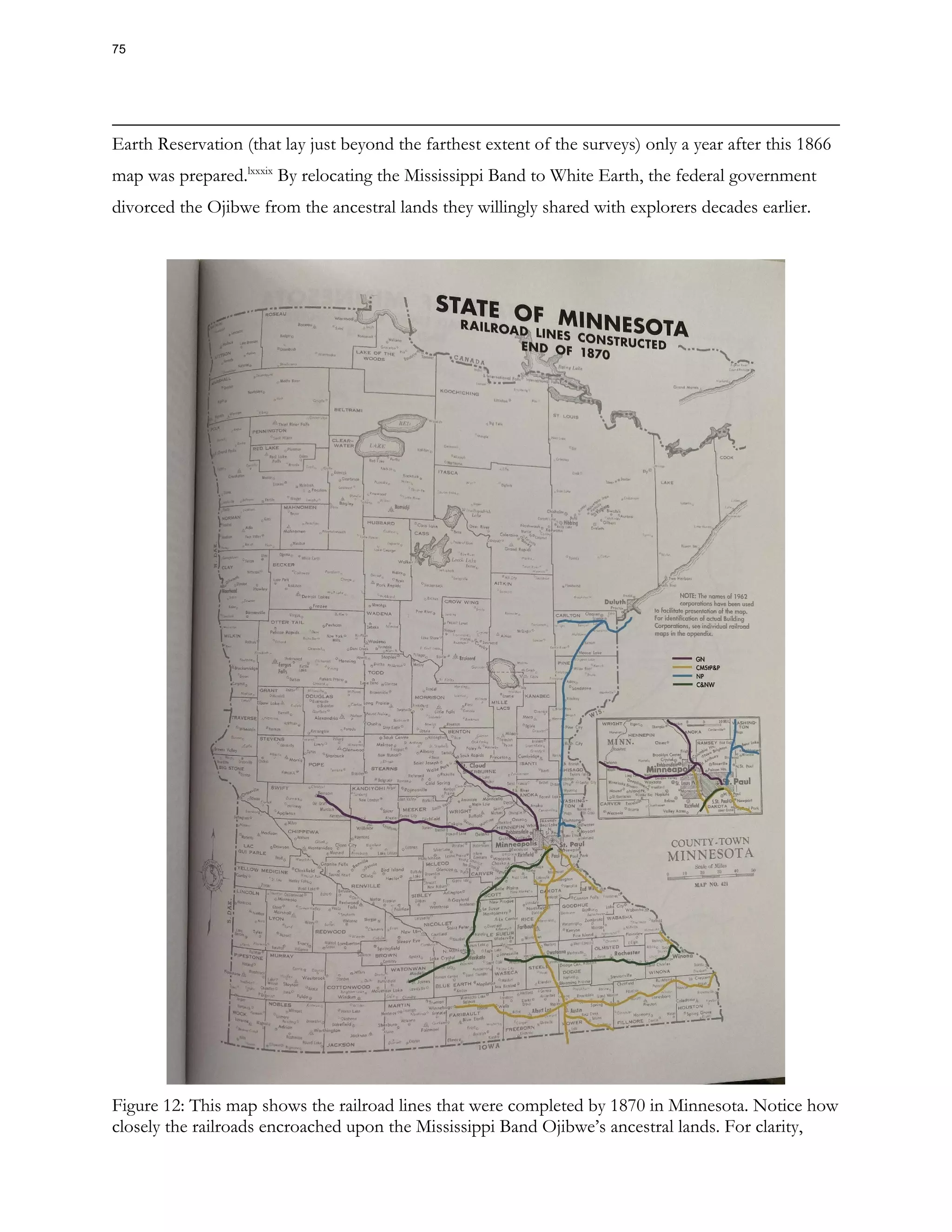

![their ancestral lands lay near Lake Mille Lacs (round lake in east central Minnesota). Compare to

figure 1 to view in context of surveys and railroad land grants. Image citation: Richard S. Prosser,

State of Minnesota Railroad Lines Constructed End of 1870 [map], in Rails to the Northern Star: A Minnesota

Railroad Atlas (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007).

In the milieu of rapid Euro-American settlement and railroad expansion, the federal government

resorted to an assimilatory reservation policy in its establishment of White Earth. While granting the

White Earth Ojibwe a swath of land encompassing grasslands served to encourage their transition to

agriculture, setting aside agricultural lands for the Ojibwe’s benefit also placed the White Earth

Ojibwe in the line of fire. By the 1870s, the Northern Pacific Railroad passed less than twenty miles

south of White Earth and Euro-American settlements sprang up along the line, leading to white

encroachment at the reservation.lxxxix

An 1887 map advertising the Northern Pacific Railroad’s lands

for sale near the reservation shows White Earth at the top of the map, and the extension of the

railroad’s land grant within reservation borders highlights the shaky security the reservation offered

its inhabitants in a region under high demand from railroads and settlers (see figures 13 and 13a). A

Northern Pacific Railroad guide book, The Great Northwest, even features the White Earth

Reservation as a tourist destination. The book urges Euro-Americans to visit “this beautiful

reservation, as fair a country as the sun ever shone upon,” stressing that visitors “are always received

with kindness.”lxxxix

The reservation’s proximity to lands conducive to settler agriculture, in addition

to ploys by the railroad to entice Euro-Americans to the lands in and around the reservation,

exposes the power Euro-American land interests had in endangering Indigenous land sovereignty.

76](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-76-2048.jpg)

![Figure 13: This 1887 map shows lands for sale by the Northern Pacific Railroad to encourage

settlement along its line. Orange coloring denotes lands for sale. Notice the White Earth Reservation

at the top of the map; the railroad’s land grant extends into the reservation (more clearly visible in

figure 13a). This map underscores that White Earth land was highly coveted by Euro-Americans,

and consequently made visible and available for commodification through the joint pursuits of

railroad companies and public surveys. Image citation: Northern Pacific Railroad Land Department,

Map of Becker and Otter Tail Counties, Minnesota [map] (St. Paul: Land Department, Northern Pacific

Railroad, 1887).

77](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-77-2048.jpg)

![Figure 13a: This close-up view of the 1887 map clearly shows the orange lands for sale abutting the

southern border of White Earth. The dashed “staircase” line running within reservation boundaries

represents the Northern Pacific’s land grant. Image citation: Northern Pacific Railroad Land

Department, Map of Becker and Otter Tail Counties, Minnesota [map] (St. Paul: Land Department,

Northern Pacific Railroad, 1887).

The extension of the Northern Pacific’s land grant into the reservation encouraged the surveying of

reservation lands, which made the White Earth Ojibwe legible twice over: once on their ancestral

lands and once again on their reservation. The surveyors first arrived at White Earth in the early

1870s—coinciding with Northern Pacific Railroad developments in the region. By 1877, Indian

agent Lewis Stowe wrote to the Surveyor General of Minnesota requesting the “latest map of

Minnesota,” as he was “very anxious to procure one with the reservation surveyed thereon.”lxxxix

By

“procur[ing]” a surveyed map of the reservation, White Earth Indian agents acquired knowledge of

what land existed and how it was/could be used (see figure 14). This quantified legibility of White

Earth—noting every tree, brook, and clearing upon the reservation—empowered the federal

government and enabled the commissioners to coerce the Ojibwe into taking individual land

allotments in 1889.

78](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-78-2048.jpg)

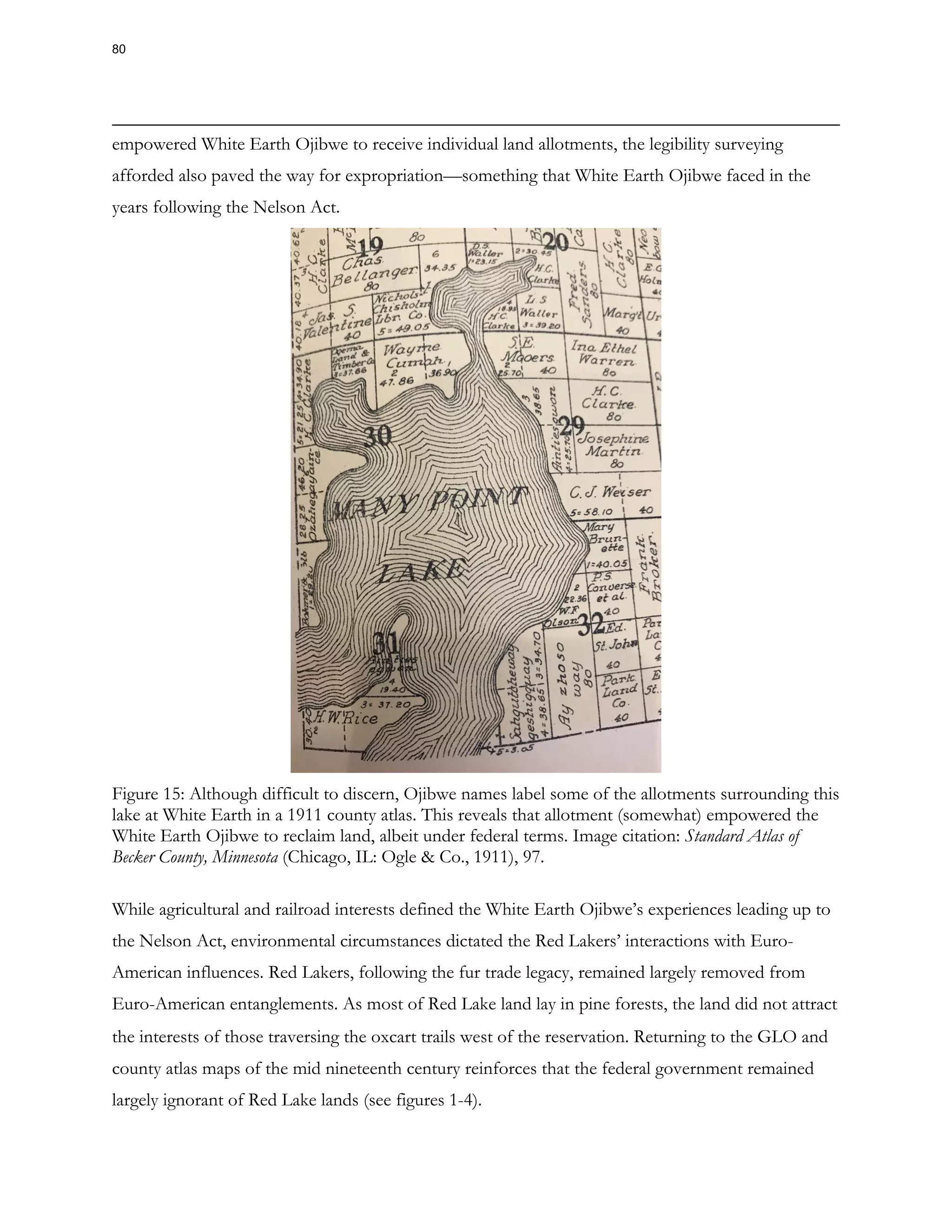

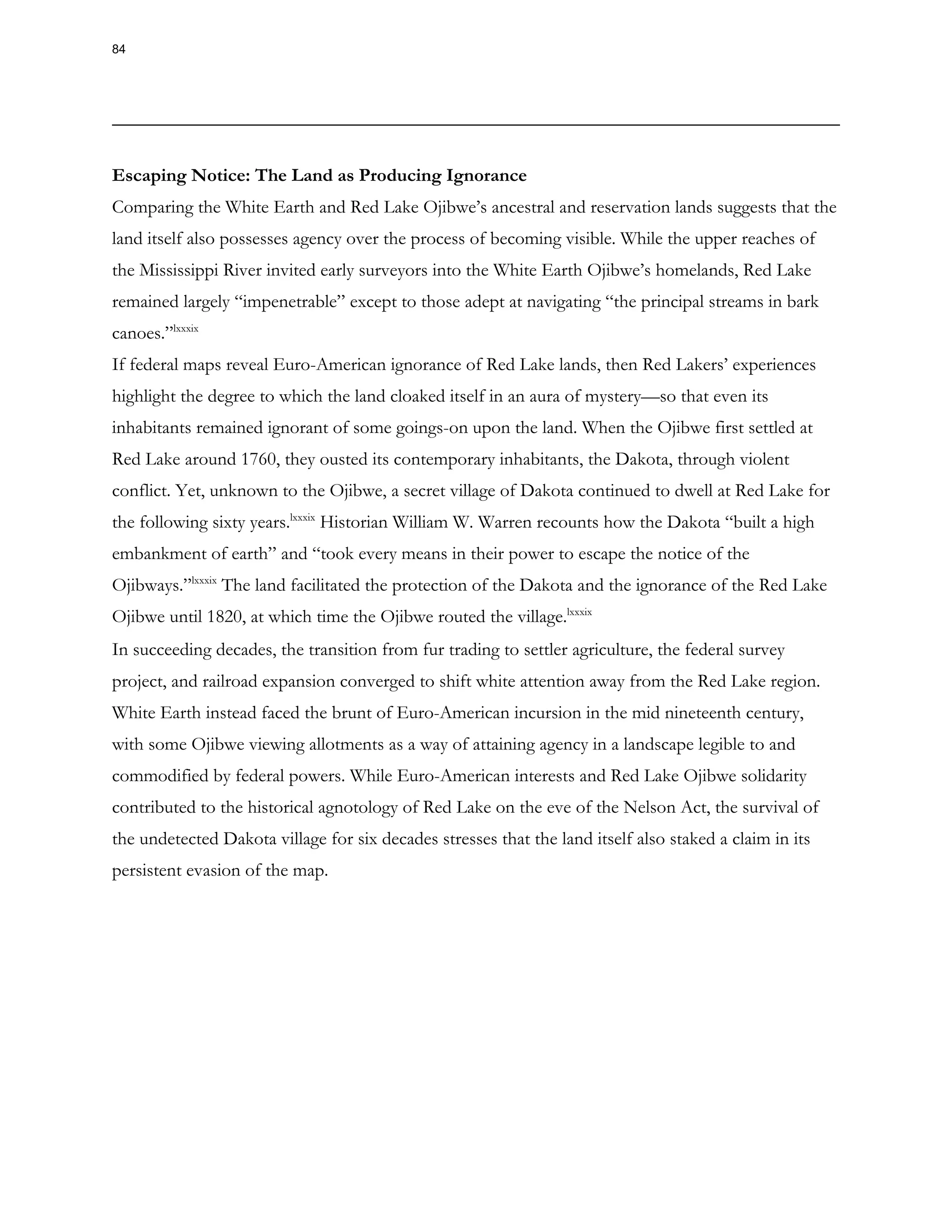

![One particular moment in Red Lake history reveals the degree to which their environmental

situation determined their path leading up to the Nelson Act. Red Lakers, unlike the White Earth

Ojibwe, always remained on their ancestral lands, but they nevertheless ceded millions of acres

through treaties. In 1863, the federal government approached the Red Lake Band and pressured

them to cede their lands stretching west of Red Lake into the Red River Valley.lxxxix

When reading

this treaty alongside Marschner’s vegetation map and the map of the oxcart trails, the agricultural

promise of the Red River Valley appears to have determined the federal government’s desire for the

lands (see figures 6 and 11). The Red Lakers ceded the lands and in so doing agreed to occupy their

remaining homelands in what officially became their reservation.lxxxix

Red Lakers experienced

dispossession as did the White Earth Ojibwe, but by inhabiting lands less conducive to settler

agriculture, they remained out of federal consciousness for a longer duration.

Revisiting figures 1–4 undermines the assumption that Red Lake remained unsurveyed because it

was geographically isolated. After Red Lakers ceded lands in the Red River Valley, GLO and atlas

maps reveal how quickly the grid extended into the ceded lands. Figures 16 and 17 also show how

quickly the railroads followed suit: their focus on tapping into agricultural resources and extending

to the Pacific coast made traversing the prairie lands of the Red River Valley more relevant than the

pinelands of Red Lake. The Red River Valley resides equally as far away as Red Lake, challenging the

use of geographic isolation to explain how Red Lake eluded the grid. If anything, the argument

presented in the 1824 travel narrative—that the forested and swampy environment at Red Lake

“rendered [the land] impenetrable”—appears a more suitable explanation for why Red Lake evaded

surveys until the 1890s.lxxxix

Red Lake’s perceived isolation emerges as a historical and environmental,

rather than a geographical, construct.

81](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-81-2048.jpg)

![Figure 16: This 1879 map of the Northern Pacific’s railway line highlights the railroad’s goal of

reaching the western seaboard. In this process, the lands west of Minneapolis and St. Paul also

became subsumed into the national market by providing agricultural produce for metropolitan areas.

Image citation: Northern Pacific Railroad Company, Map of the Northern Pacific Railroads and

Connections [map], 1:7,500,000 (Chicago, IL: Rand McNally, 1879).

Figure 17: Another transcontinental railroad line, the Great Northern, prepared a map in German in

1892 to attract prospective settlers west. While the line stretches to the West, the abundance of

regional lines in the Red River Valley (see the inset featuring the valley) reveals that the regions just

south and west of Red Lake drew settlers’ interest. On the map, Red Lake itself lies just beyond the

area of interest, whereas White Earth is subsumed by railroads. Image citation: Great Northern

Railway Company, Great Northern Railway line and connections [map], 1:2,730,000 (St. Paul, MN: Great

Northern Eisenbahn, 1892).

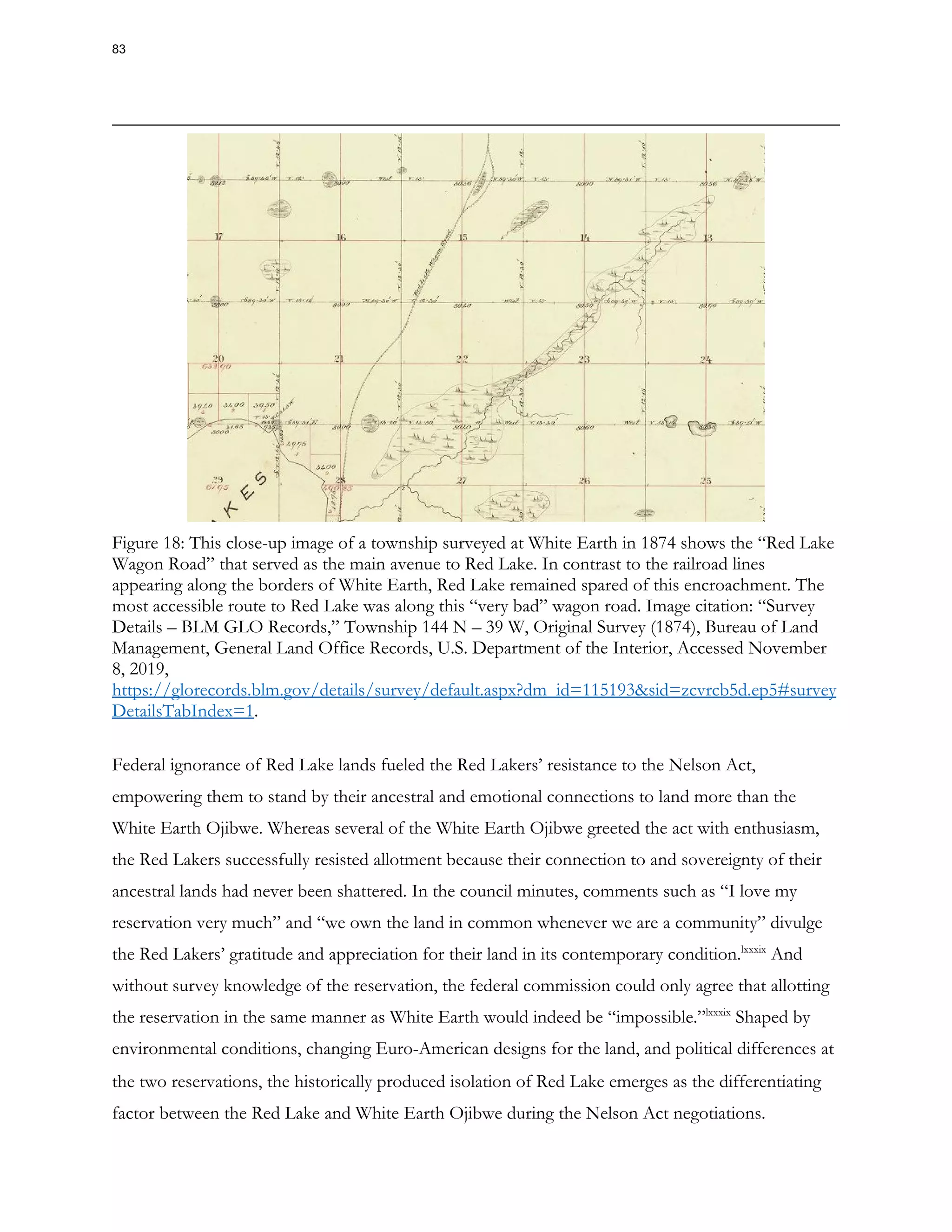

The lack of decent infrastructure—even roads—to Red Lake illuminates the challenges facing the

federal government in gaining knowledge of the land. While the government’s disinterest in the land

fostered ignorance, the absence of navigable roads reinforced this ignorance. Figure 18 features an

1870s survey conducted at White Earth, which shows a “Red Lake Wagon Road” running through

some of the township plats. Red Lake remained so removed from the railroad that the White Earth

Agency delivered Red Lake’s mail on a weekly basis. In White Earth’s council minutes in 1889,

Kesh-ke-we-gah-bowe complains that the road to Red Lake is “a very bad one,” leading him to

repair his wagon weekly to “carry…the mail.”lxxxix

That White Earth Ojibwe struggled to reach Red

Lake via their road underscores the multiplicity of factors leading to Red Lake’s territorial invisibility.

82](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-82-2048.jpg)

![history. By basing any periodization solely around the East India Company’s own history, South

Asia, as a subject with its own history, is necessarily reduced to a paradigmatic afterthought. In

reality, this is not the case, as the Company and the Mughals coexisted in South Asia from the EIC’s

inception until the First War of Independence. Eschewing this Eurocentric periodization is thus

necessary in any analysis of the Company.

This periodization presents an issue when analyzing a subject which involves both eras. The

East India Company’s sovereignty did experience a great deal of change between 1756 and 1766, but

the idea that an overnight transition from ‘trading’ to ‘empire’ occurred is categorically false. Thus,

this paper presents a selective but holistic investigation into the Company’s sovereignty, consciously

reworking traditional periodization. I make use of Sanjay Subrahmanyam’s temporal schema, with

the period before the Battle of Plassey defined as the ‘Age of Contained Conflict,’ where Europeans

had little terrestrial military power, and thus existed firmly in the Mughal’s orbit.lxxxix

Using this

framework, the constraints on the Company’s actions become apparent, as their dependency on

cooperation with the Mughal Empire becomes clear. The period following the Battle of Plassey and

the Treaty of Allahabad consumes only a short part of this study, for it did not take long for the

British government to establish a Governor-General in Calcutta, establishing oversight over the

Company’s actions. In any case, the period between 1765 and 1773 was marked by the newfound

political, economic, and social reality the Company found itself in, grappling with how to best

“defend, govern, and exploit [its] vast empire.”lxxxix

During this entire period, however, the Company’s relationship with South Asian actors,

analyzed through the former’s sovereignty, was more interactive than many histories may suggest.

Early modern South Asia was neither despotic nor constitutional; the area possessed its own

modalities, dominated in many ways by the Mughals and their patrimonial-bureaucratic political

culture. In fact, prior to the 1740s, the Company’s role was that of an insignificant South Asian

93](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-93-2048.jpg)

![Carnatic Wars in 1746. These conflicts, which pitted the EIC against their French counterpart, the

Compagnie française pour le commerce des Indes orientales, were “a seventeen-year struggle […] to exclude

the other from trading in India by obtaining a preponderant exclusive influence in three major

Indian governments in the east of the subcontinent – in the Carnatic, the Deccan and Bengal.”lxxxix

Ultimately, the Carnatic Wars resulted in the destruction of French power in South Asia, leaving the

EIC as the only East India Company with the ability to wield considerable terrestrial military power.

Towards the end of the Anglo-French conflicts, however, the nawab of Bengal, Siraj ud-Daulah

(r.1756-1757), seized Calcutta and Fort William, prompting a British response, which ultimately

culminated in the Battle of Plassey and the nawab’s replacement with Mir Jafar (r.1757-1760; 1764-

1765). Another spasm of conflict, known as the Bengal War, which lasted from 1759 to 1764 and

was contested by the British and a coalition of Indian forces, including those of the weak Mughal

Emperor, ended in a decisive Company victory. The 1765 Treaty of Allahabad, which concluded the

Bengal War, saw the Company made diwan of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa by the defeated Emperor

Shah Alam II (r.1760-1788); moreover, the Company also became the suzerain over nawab

Muhammad Ali Khan Wallajah (r. 1749-1795) of the Carnatic.lxxxix

The Treaty of Allahabad consigned to the Company a new set of sovereign responsibilities.

The Treaty of Allahabad made the Company a territorial imperial power, rather than merely a

commercial one. This new sovereignty was borne not out of necessity but rather out of an

‘unpremeditated’ response to challenges posed by the rise of a French rival, the decline of central

Mughal power, and a short-sighted interpretation of Company goals.lxxxix

Importantly, the London-

based Directorate and the Company’s South Asian leadership had different perceptions of the

Company sovereign interest. For the Directorate, a traditional policy of defence, especially against

incursions that threatened the Company’s commercial position, had been in place for much of the

EIC’s history. In a written defense of its wars, the Company cited that they had entered the war

106](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-106-2048.jpg)

![“merely in Support of Mahmud Ally, and in Defence of their commercial Rights, Security to those,

and a reasonable Indemnification for their Losses.”lxxxix

Conversely, Clive’s aggressive interpretation

of the Company’s sovereign interest was not antithetical in the greater context of the EIC’s history.

The Company had long been pursuing a belligerent diplomatic program in pursuit of commercial

and political grants in South Asia. In this light, Clive’s actions and the Company’s growing political

responsibilities in India after 1765 hint at continuity, instead of change, in their sovereign policy. For

165 years, the Company’s South Asian policy showed striking continuity; their politics were almost

entirely independent from the British government and they largely did as they pleased, including

with respect to warfare.

In any case, the EIC had moved away from the hallmarks of both aforementioned

periodizations. Regarding the traditional view, the Company had exited its commercial phase, as “Its

funding base had been radically changed in 1765 with the acquisition of the diwani and extensive

territorial power in Bengal, [which] … had to be protected.”lxxxix

Thus, there emerged newfound

military prerogatives that became central to the Company’s sovereignty; whereas it had derived its

profits before the Treaty of Allahabad largely from commerce, it now controlled a relative gold mine

in the form of tax collection over a populous and wealthy area. In Subrahmanyam’s view, the EIC,

by defeating the Mughals and their confederates in a terrestrial conflict, had progressed past the ‘Age

of Contained Conflict.’lxxxix

No longer was the Company merely an imperialistic commercial

enterprise with a dispersed collection of small South Asian territories; now, the EIC was a genuine

terrestrial military and imperial power with a sizeable domain, unconstrained by existential threats to

its ability to generate revenue.

Part V: Deletion, 1765-1773

After the 1690s, and through 1765, British politics affected but did not change the

Company’s sovereignty in South Asia. The relationship between the Company and Parliament was

107](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-107-2048.jpg)

![both in London and in South Asia. The result was that the Company was now a subject of the

British government, having entirely lost its autonomy.lxxxix

Part VI: Conclusion

In the end, the Company’s sovereignty was destroyed as a result of the expansion of its

scope. The Treaty of Allahabad put the Company into an unprecedented administrative and political

position, one that was in open contradiction with its charter as a mercantile corporation and in direct

opposition with Parliament’s fiscal concerns. Parliament, using its prerogative assumed during the

creation of the United Company, decisively solved this contradiction by absolving the Company

from its autochthonous administrative sovereignty and from the authority associated with its Mughal

offices.

James Turner Johnson, in his 2014 work Sovereignty: Moral and Historical Perspectives, mistakes

the sovereign commercial-political relationship between Europeans and non-Europeans, and, in the

process, shows the value of analyzing the Company’s tripartite sovereignty. He notes that

“[European] Trading relations with other parts of the world began in the form of an organized

reciprocity, but this changed to hegemonic relations first in the conquest, settlement, and

fortification of centers designed to support trade and exploration […].”lxxxix

The Company’s

sovereignty cannot be grounded in either organized reciprocity or hegemonic relations. Drawing on

sovereignty from its charter, Mughal concessions and farmans, and its own administrative and

diplomatic practices, the Company independently asserted itself in South Asia through sovereign

adaptation, always armed with the goal of expanding their revenue and, eventually, seizing territory.

This atypical process defies Johnson’s typification of European sovereignty in an imperial context.

The Company was neither a political equal of the Mughal Empire or a hegemon-in-waiting; it was

defined by its flexible, tripartite sovereignty, adapted to ever-changing political circumstances.

111](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-111-2048.jpg)

![Introduction

A Torah in South Texas

In a small synagogue south of San Antonio, a Torah sits in a brightly lit display case to the side of

the sanctuary. The scroll is open to a passage from the book of Exodus, the familiar Hebrew text of a

song Miriam and Moses sang after escaping Egypt and crossing the Red Sea. All Torahs, including

this one, are handmade—the calligraphy copied, the wooden rollers carved and polished, the pages

of parchment stitched together one by one. This scroll, however, was made many decades ago,

thousands of miles away from Texas, in a country that no longer exists. So why is this Torah here, in

a temple on the Gulf Coast, behind glass? A small handwri en sign in the front of the case provides

an answer:

This Torah, from Domažlice, Czechoslovakia, was one of the few that survived

the Holocaust. It was confiscated by the Nazis during World War II, and was

rescued after the war by the Westminister [sic] Synagogue in London, England.

It is on permanent loan to Temple Beth El, and its acquisition and display was

made possible through the generosity of Dorothy and Harry Trodlier.

Rabbi Kenneth D. Roseman, the rabbi-emeritus of this Corpus Christi congregation, wrote about the

spiritual significance of having an artifact from the Holocaust in the temple: “It is not only the

physical scroll that has come to rest in South Texas. I believe that the souls of all the Jews of

Domažlice, the people who read from this Torah...whose lives were mercilessly cut short, have also

migrated to our city and into our congregation.”1

The gravity of this display was not lost on me when I first came across the Torah as an

eight-year-old, but much of the Torah’s history was. For many years, I imagined that it had been

smuggled out by an emigrating family, or ripped from the clutches of Nazis, a dramatic saga in the

style of a movie like Monuments Men. To my surprise, however, I learned that the Domažlice Torah

1

Kenneth D. Roseman, Of Tribes and Tribulations, (Wipf & Stock Publishers: 2014), 24.

117](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-117-2048.jpg)

![Prague’s Zentralstelle, fancied himself a man of culture and scholarship, and that overseeing the

museum was his pet project.22

In 1941, Jewish religious practices in the Protectorate were banned. The Nazis began

deporting Jews to Terezín, an Austro-Hungarian fortress converted into a hybrid transit camp and

ghetto. The Jewish community in Prague “was compelled to set up a Treuhandstelle [trust office] for

overseeing the confiscated assets of Jewish deportees,” with requisitioned property to be stored

within the Jewish museum, including the now-empty synagogues in the complex.23

Notably, the last

entry in the museum’s visitors’ book was dated November 24th, 1941, just as the first regular

transports to Terezín had begun.24

The Jewish Museum was no longer a public institution. While the

museum would continue to curate exhibitions throughout the war, these were only on display for

Nazi officials and their guests. In 1942, the museum was rebranded by the Nazis as the “Central

Jewish Museum.”25

In the spring of 1942, the deputy of the Protectorate’s Zentralstelle, Nazi officer Karl Rahm,

asked the Jewish community to circulate a letter requiring all books and “historic and historically

valuable” objects from outlying communities be sent to Prague to be sorted, organized, and

warehoused in the museum.26

In the summer of that year, boxes and parcels from twenty-nine

provincial communities arrived in Prague.27

Some communities sent one or two museum-worthy

objects, such as military medals or historical letters from their local archives. But in other areas,

where the deportations were becoming increasingly intense, the instructions in the letter were

27

Pavlát, “The Jewish Museum During the Second World War,” 125.

26

Dr. Karel Stein, “Circular Letter: 3 August 1942,” reproduced in Magda Veselská, Archa paměti: Cesta pražského

židovského muzea pohnutým 20. stoletím [The Ark of Memory: The Journey of the Jewish Museum in the Turbulent 20th

Century (Prague: The Jewish Museum in Prague, 2012), 65.

25

Sayer, Prague, Capital of the Twentieth Century, 138.

24

Pavlát, “The Jewish Museum During the Second World War,” 124.

23

Ibid., 47-48.

22

Veselská, “‘The Museum of an Extinct Race,’” 63, 66-67.

7

124](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-124-2048.jpg)

![Veselská notes in an essay that Volavková’s book was “intended as an elegy, not a factual analysis of

wartime events”: this version of Volavková’s conceptualization of the whole museum as a memorial

was rhetorical and personal.58

Volavková also designed and oversaw the installation of a more formal, traditional

memorial to commemorate all Czech victims. The memorial she designed simply lists in red and

black ink the 77,297 names of Jews of Bohemia and Moravia who died, with birth and death dates,

on an inner wall of the Pinkas Synagogue, one of the buildings of the Jewish Museum’s complex. As

she imagined it,

Those who during the war were degraded into numbers and transports again received a

home and a human face. They are freed by the humble script, written with piety, by an

anonymous art that is almost medieval.59

Naming all of the Jewish victims returns a feature of individuality that had been denied. From a

distance, the sheer number of names blurs into abstraction, an overwhelming visual texture of static.

The lists look like the dense handwritten texture of a Torah scroll. Some believe that “the monument

[in Prague] was the largest grave inscription in the world,” rivaled only by Edwin Lutyens’ Thiepval

Memorial in France, which lists 72,000 men whose bodies were never recovered during the Battle of

the Somme during the first World War.60

Leo Pavlát, the current director of the Jewish Museum, states that “the museum as a whole,

by some cruel fate, had become the only large memorial to the several generations of Czech and

Moravian Jews.”61

But this memorial came under threat almost as soon as the war ended. In the

political turmoil of the post-war period, the museum struggled to relocate, maintain, and safely store

its enormous collection. The museum was nationalized in 1950 following the communist coup in

61

Pavlát, “The Jewish Museum During the Second World War,” 129.

60

Sayer, Prague, Capital of the Twentieth Century, 137.

59

Hana Volavková, quoted in Rybár, Jewish Prague, 276.

58

Ibid., 125.

15

132](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-132-2048.jpg)

![century, but some were much older, the very earliest dating back to 1690.71

Seeking a patron to bring

the Torahs out of Czechoslovakia, Estorick reached out to an acquaintance, the London

philanthropist Ralph Yablon, a member of the Westminster Synagogue.72

Yablon volunteered to pay

for the Torahs and their shipment to Westminster Synagogue, so long as the scrolls were fit to use.

Before they were purchased, Yablon sent his friend Dr. Chimen Abramsky, a professor of Hebrew at

University College London and a Sotheby’s consultant for the sales of Hebrew books and ritual

objects, to examine them. He visited Prague for twelve days to evaluate the scrolls’ condition as best

he could, appraising about five hundred. Abramsky estimated that “two-thirds were kosher, or

could be made so.”73

The focus on the scrolls’ Jewish utility, both in Abramsky’s original evaluation and

subsequent appraisals, illustrates the clear religious rationale of the project. Torahs that are not

kosher are called pasul, or defective, and cannot be used during services unless they are properly

repaired. Disqualifying flaws can include the oxidation of ink, tears of a certain length, or the

misspelling of certain words. The religious laws governing the creation, care, and disposal of Torah

scrolls are exacting, intended to treat a text bearing the name of God with proper reverence.74

In the

hierarchy of Jewish ritual objects, the parchment of the Torah scroll—excluding the wooden

rollers—is of the highest echelon, as it bears the name of God. Because of this, a scroll damaged

74

Even today, Torahs are prepared by trained scribes, called sofers, with the same materials and methods used

hundreds of years ago. Torah scrolls are made of sixty-two individual sheets of parchment, the outer layer of treated

and dried skin from a kosher animal—when properly prepared, parchment is more flexible and durable than paper.

The exact text of the five books of Moses is copied using the quill of a kosher animal—usually a turkey—with four

columns of text on each sheet, then hand-sewn with sinew, and bound to wooden rollers. The process can take over a

year to complete.

73

Correspondence from Ralph Yablon to Harold Reinhart, 5 December 1963. Memorial Scrolls Trust Archive

[uncatalogued]. Czech Memorial Scrolls Museum, London, England [hereafter MST.]

72

The congregation had recently separated from the West London Synagogue, the original Reform congregation in

the United Kingdom. Westminster Synagogue was and is still based in Kent House, a property in the neighborhood

of Knightsbridge that had once been an aristocratic residence; see Bernard, Out of the Midst of the Fire, 27-28.

71

Bernard, Out of the Midst of the Fire, 35.

19

136](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-136-2048.jpg)

![Jewish Question.88

The JCR intended to transplant “heirless”89

property from Germany to

international locations with

vibrant communities—centres of Jewish life in which these ritual objects and books would be

circulated and used…. [H]ow much material each community would receive was

commensurate, in part, with the Jewish population in the community, the recipient

organisations’ long-term stability and their ability to care for the material.90

In 1949, the director of the JCR believed that this meant the objects should only go to New York City

or Israel.91

Eventually, its scope was widened to include Great Britain, Europe, and other

international locations.92

Items were incorporated into museums and study centers, new libraries,

reintroduced to religious use in synagogues, or disposed of according to Jewish law. A wide and

varied community had rights and claims to European Jewish culture, and the items were used

however the individual communities saw fit. None of the Torahs or ritual objects distributed by the

JCR were considered memorial objects, either individually or collectively—in fact, most of the

Torahs they dispensed went to Israel, and the majority were buried.93

The Memorial Scrolls Committee at Westminster Synagogue first met on February 10th

, 1964.

First, the scrolls were to be carefully reappraised and renumbered according to a new in-house

system to fix some discrepancies in the original inventory from Prague. The Torahs were then to be

classified by quality, recorded as “kasher [sic], repairable, some columns usable, or completely

93

Burial was the primary outcome for damaged ritual objects in America, as well: “Those objects that could not be

distributed due to irreparable damage were set aside for burial by the Synagogue Council of America…at the Beth El

Cemetery in Paramus, New Jersey, on 13th

January 1952. The date was chosen for its proximity to the 10th

of Teveth, a

historic day of mourning and fasting proclaimed as a memorial to the Jewish victims of persecution in all eras. A

tombstone was dedicated ten months later, over the graves of the buried religious objects.” See Herman, “’A Brand

Plucked Out of the Fire’,” in Neglected Witnesses, 42-43.

92

Herman, “’A Brand Plucked Out of the Fire’,” 31.

91

Rauschenberger, "The Restitution of Jewish Cultural Objects,” 200.

90

Herman, “’A Brand Plucked Out of the Fire’,” 33.

89

A legal debate in Germany arose over ownership of some of the cultural material between the JCR and small,

recongregated Jewish communities in Germany; see Ayaka Takei, “The “Gemeinde Problem”: The Jewish Restitution

Successor Organization and the Postwar Jewish Communities in Germany, 1947-1954,” Holocaust and Genocide Studies,

Volume 16, Issue 2 (2002), 266–288.

88

Rauschenberger, "The Restitution of Jewish Cultural Objects,” 198.

23

140](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-140-2048.jpg)

![2. Should youth and teaching organizations have preference as they bring up the next

generation of Jews? 101

Ensuring continuous use in a new, stable environment was a clear priority. The comments also

belied an implicit bias towards Progressive Judaism, the British version of what would be called

Reform Judaism in the United States. Waley stated that, on some of these matters, he has “quite

decided views, on others none at all,” adding that he believed “each country which has absorbed

any central European refugees should have a Memorial Scroll whether they have asked for one or

not.”102

In a letter to Rabbi Reinhart six days later, Sir Seymour Karminski outlined his ideas of what

principles should be used to sort through the applicants. Karminski first prioritized “congregations

with substantial Czech connections, in Israel or elsewhere,” then “refounded European

congregations (e.g. in Holland) who are short of scrolls” and new congregations in the United States.

He gave the example of a new synagogue in Maryland.103

Many of these new communities did not

have Torah scrolls of their own, and buying a new Torah scroll for a congregation could be

prohibitively expensive.

Most of the Torahs were allocated to synagogues or Jewish institutions, but distribution was

not limited to Jewish spaces exclusively. In an early meeting, the Committee probed whether the

more damaged Torahs could “be used for museums or libraries, or must they be destroyed

according to ritual.”104

In response, Abramsky wrote that “with regard to the posul Torahs the Din

[the Jewish Law] says that they should be buried, but this is not obligatory, they can be used also as

museums [sic] pieces or as decorative pieces for Simchat Torah….there are many Torahs amongst

104

MST, Memorial Scrolls Committee Minutes, 20 February 1965.

103

MST, correspondence from Sir Seymour Karminski to Harold Reinhart, 26 February 1965.

102

MST, correspondence from Frank Waley to Harold Reinhart, 24 February 1965.

101

MST, correspondence from Frank Waley to Harold Reinhart, 24 February 1965.

25

142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-142-2048.jpg)

![appropriate for religious use, with thirty-three of the scrolls classified as “irreparable.”120

Warhaftig

wrote that “disqualified Scrolls have been duly deposited in our Guenizah [sic].”121

It was not only a private dispute. The Jerusalem Post catapulted the story into the public eye.

The headlines were not flattering: “Religious Ministry rejects 33 scrolls: Sifre Torah from London no

good.”122

The Memorial Scrolls Committee was horrified that scrolls had been buried without their

consent, that their experts were called into question, and that the misunderstanding had made it so

quickly to the newspapers. Reinhart was given an opportunity to write a press statement after he

travelled to Israel and met privately with Warhaftig in March of 1966, but his statement was edited

without his approval after he had flown back to London.123

The new headline was “Some of gift Tora

[sic] scrolls found usable: Progressive group to get one,” with that article bearing a subheading,

“PROMISE BROKEN.”124

Additionally, the congregation’s name was recorded in the article as

“Westminster Progressive Synagogue,” inserting a denominational adjective not actually present. In

April, Reinhart wrote another angry letter to Warhaftig, stating outright that

Prejudice is operating in the matter of the Scrolls. An ideological war which is being waged,

is lamentably insinuated into the business of the sacred Scrolls. This seems to be apparent in

all the publicity, where statements are repeatedly mixtures of “requests from ‘Progressives;”

with “unfitness of Scrolls”.125

Reinhart also took offense with mentions of the cost, “an utterly callous estimate of the Czech

memorial Scrolls, every one of which is a sacred treasure, not only because it is a copy of our Torah

but also because it is a brand from the burning126

, which sears our very soul.”127

Correspondence

127

Ibid.

126

A Biblical phrase from Amos 4:11, which refers to something that is miraculously saved at the very last instant.

125

MST, Correspondence from Harold Reinhart to Dr. Zerach Warhaftig, 18 April 1966.

124

MST, clip of article from The Jerusalem Post, n. d.

123

MST, “Confidential Report on Meeting in Israel with Dr. Warhaftig” by Harold Reinhart, 8 March 1966.

122

MST, clip of article from The Jerusalem Post, n. d.

121

Ibid.

120

MST, Correspondence from Dr. Zerach Warhaftig to Harold Reinhart, 14 February 1966.

29

146](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yup-merged-210815224924/75/The-Yale-Historical-Review-Fall-2020-Issue-146-2048.jpg)

![As the Torahs spread to their new locations, some to Jewish communities, some to secular

museums and libraries, there was a flurry of discussion about the appropriate use of the scrolls as

memorials. An article in the Central Conference of American Rabbis’ Journal—a Reform

publication—considered whether a Torah should be kept in “a museum case or in [the] ark,” the

most sacred space in the synagogue.131

Torahs are to be handled and stored with utmost respect, so

the Rabbinic analysis evaluated which setting would afford the scroll the most reverence. In the

journal, Solomon Freehof worried that placing a pasul Torah in a display case with other Judaica

might equate the scroll with less important objects. He recommended placing even a damaged Torah

in the ark, so the scroll will be included in the regular course of worship: “Whenever the Ark will be

open for the Torah reading, the congregation will rise in respect for all the scrolls in the Ark and this

scroll, now permanently rescued from captivity, will thus be honored among them.”132

In 1988, an

incensed reader wrote a letter to the editor of The Jewish Chronicle about the “shameful revelation

that Czech scrolls appropriated as memorials are to be found at Westminster Abbey, in the Royal

Library at Windsor Castle,” and other secular spaces like university libraries.133

From his

perspective, the practice was “totally contrary to the basic code of Jewish law, which prescribes that

holy scrolls should be deposited within the arks of synagogues” or buried in a genizah. Two

spokespeople of the Memorial Scrolls Committee responded in the Chronicle, highlighting the fact

that while most resided within Jewish institutions, “some 800 have already been restored and sent to