The Yale Historical Review is an undergraduate publication that showcases exceptional historical research from Yale students. The Spring 2021 issue features five outstanding papers exploring topics such as World War II psychology, testimonies of comfort women, Irish support for Palestinian self-determination, the early history of x-ray technology, and the Franco-American orphanage in Lowell, Massachusetts. The editorial team emphasizes the importance of community engagement and plans to expand their online content and connections with the Yale community.

![SPRING 2021

THE FRANCO-AMERICAN

ORPHANAGE

Immigrant Community and the Development of the

Modern Welfare State,1908–1932

by Sophie Combs, University of Massachusetts Lowell '20

Classroom of “orphans” circa 1920. [1]

Written for a Directed Study

Advised by Professor Robert Forrant

Edited by Esther Reichek and Aaron Jenkins

VOLUME XI ISSUE I SPRING 2021

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yhrspring2021-211020115003/85/YHR-Spring-2021-6-320.jpg)

![N 1908, OWNERSHIP of the Frederick

Ayer Mansion in Lowell, Massachusetts

passed from a millionaire investor to a com-

munity of immigrant workers. This change

corresponded to the industrial city at a moment of social

reckoning.At the time that organizers from St.Joseph’s pa-

rish fundraised to buy the property from the Ayer’s estate,li-

ving conditions and wages had degraded to abject lows.This

sprawling fortress—four stories tall, complete with stained

glass,pillars,and67rooms—wasatestamenttothefortunes

amassed in local mills and,subsequently,became a home for

the children of mill workers.In place of an elaborate house,

the French-Canadian church established an orphanage for

the care and education of children with working families.

The Franco-American Orphanage (FAO), first a manor

and then a childcare facility, can be considered emblematic

of the dual versions of Lowell created by industry in the

19th and early 20th centuries.1

Lowell’s orphanage was the result of local acti-

vism and can be understood as a formalized structure of

mutual aid. Financially, the FAO was symbiotic with its

community, both catering to and supported by the im-

migrant population of the city’s Little Canada.Founders

intended that the institution to provide short- and long-

term childcare services for families; in remembrance of

this objective,board members articulated,“In those days,

orphans did not receive any special consideration by the

civil authorities and the burden of education and caring

for those unfortunate children fell on the shoulders of

relatives.”2

By situating the FAO within the legacy of

American mutual aid, this paper asserts an alternative

interpretation of the orphanage in which the institution

1 This paper relies upon archival documents translated by the author from the original French. Additionally,

the character of the orphanage was assessed through several interviews of a former resident by the author. "Cul-

tural Resource Inventory – History of Ayer Home incl. Photos," Box 1 Franco-American Orphanage/School collec-

tion, Center for Lowell History.

2 Most influential in plans for the FAO was Reverend Joseph Campeau, who considered the orphanage his

"dream." For most of the FAO’s early life, board members were active members in St. Joseph’s Parish and/or local busi-

nessmen while the daily activities of the orphanage were run by women. "Fr. Campeau brings Grey Nuns to Orphan-

age," Box 1 Franco-American Orphanage School collection, Center for Lowell History.

3 Peter Kropotkin, Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (London: Heinemann, 1902. Reprint, Mineola, New York:

Dover Publications, 2012), 7-8.

4 Donations varied in size and originated entirely from the Greater Lowell area. "Album Historique: Paroisse St.

Joseph Lowell, Mass. 1916," Box 1 Franco-American Orphanage/School collection, Center for Lowell History.

was the product of grassroots collaboration rather than

philanthropy in the patronizing sense.This reconceptua-

lization of the institution deviates from an individualistic

narrative of progress to one where the contributions of

working families are central.As expressed by the original

theorist of mutual aid, Peter Kropotkin, in 1914:

The leaders of contemporary thought are still inclined to

maintain that the masses had little concern in the evolu-

tion of the sociable institutions of man, and that all the

progress made in this direction was due to the intellectual,

political, and military leaders of the inert masses. […]The

creative, constructive genius of the mass of the people is

required whenever a nation has to live through a difficult

moment in its history.3

Ordinary people were responsible for the exis-

tence of the FAO.Notably,a donation campaign in 1914

to pay the $30,000 mortgage exceeded its goal by nearly

$10,000 and owed its success in large part to the contri-

butions of other immigrant groups.4

In following years,

the orphanage accepted increasing numbers of children

with Irish, Italian, and Syrian backgrounds. The FAO

was at once an institution rooted in its immigrant com-

munity, dedicated to the preservation of French-Cana-

dian heritage, and instilled with an ethos of multicultu-

ralism. As such, the orphanage can serve as a crucial case

study in grassroots organization.

In a broader context, social relief that was built

up from the grassroots had a long-standing effect on the

landscape of American welfare.In line with scholarship

by Matthew Crenson and Peter Fritzsche (1998), this

paper bolsters their claim that “welfare echoed charity

and its child-centered character recalled the institutio-

nal purpose of the orphanage itself,” positing that or-

phanages were the foundation, functionally and ideo-

INTRODUCTION

I

2

THE FRANCO-AMERICAN ORPHANAGE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yhrspring2021-211020115003/85/YHR-Spring-2021-7-320.jpg)

![logically, for subsequent developments in public relief.5

Jessie Ramey (2012), in the same vein, emphasizes the

agency of working-class people in establishing insti-

tutions thereafter absorbed into governmental struc-

tures. “Families were active participants in the history

of institutional childcare, making decisions and choices

that affected the development of early social welfare,”

Ramey notes.6

It is this process, wherein governmen-

tal structures are based in the charities that precede

them, which creates the decentralized, variable systems

of welfare coined by Alan Wolfe (1977) as a “franchise

state.”7

Michael Katz (1986) adds that “the boundaries

between public and private have always been protean

in America.The definition of public as applied to social

policy and institutions has never been fixed and unam-

biguous.”8

The FAO exemplified this ambiguity; it was

at once a private organization and one that received

funding from the Massachusetts government for acting

on its behalf. Institutions such as the FAO were the

product of mutual aid and later, to varying degrees, ab-

sorbed into the state. Mutual aid and American welfare

5 Matthew Crenson and Peter Fritzsche, Building the Invisible Orphanage: A Prehistory of the American Welfare

System (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009), 325.

6 Jessie Ramey, Child Care in Black and White: Working Parents and the History of Orphanages (Chicago: Univer-

sity of Illinois Press, 2012), 1.

7 Alan Wolfe, The Limits of Legitimacy: Political Contradictions of Contemporary Capitalism (New York: Free Press,

1977). For further reading on decentralized welfare vis-à-vis orphaned children, see: S.J. Kleinberg, Widows and Orphans

First: The Family Economy and Social Welfare Policy, 1880-1939 (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2006).

8 Michael B. Katz, In the Shadow of the Poorhouse: The Social History of Welfare in America (New York: Basic

Books, 1986), 2.

have in this way a historically porous relationship.

While immigrants created the model for com-

munity assistance in Lowell, top-down governmental

reform aimed to discriminate against immigrants dee-

med unassimilable into white society.In Massachusetts,

policymakers espousing eugenic and nativist beliefs

were instrumental in dismantling generalized institu-

tions of relief and replacing them with specialized insti-

tutions of rehabilitation. Reorganization of the welfare

state relied upon an ideological dichotomy between

“deserving” and “undeserving” paupers, with the lat-

ter subject to new apparatuses of policing. This paper

highlights the interrelation of ideology and structu-

ral implementation as articulated by John Mohr and

Vincent Duquenne (1997), who state:

Most historical accounts of social-welfare institutions

suggest that (1) the institutional logic of relief is com-

posed of two elements—a system of differentiated re-

lief practices (outdoor relief, the poorhouse, etc.) and

a system of symbolic distinctions consisting of various

The Ayer Mansion turned orphanage at an unknown date. The original 1859 house, the extension built in

1913, and the grotto for religious ceremonies are visible. [2]

VOLUME XI ISSUE I SPRING 2021

3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yhrspring2021-211020115003/85/YHR-Spring-2021-8-320.jpg)

![Increasing differentiation and classification of those re-

quiring care, together with the tendency toward centra-

lization under State control of provision for these classes,

and the use of the family home instead of the institution as

a means of providing for dependent,neglected,and certain

classes of delinquent children.12

Classification of welfare recipients for the pur-

pose of separating, specializing in,or denying care was

foundational to Massachusetts reforms throughout

the 19th and 20th centuries. Paupers were divided

into official categories:

The poor are of two classes:first,the impotent poor,in which

dominion are included all who are wholly incapable of

work, through old age, infancy, sickness, or corporeal debi-

lity. Second, the able poor, in which denomination are in-

cluded all who are capable of work, of some nature or other,

but differing in the degrees of their capacity and the kind of

work of which they are capable.13

It was the understanding of this 1821 report that

the“evils”of poverty originated from the“difficulty of dis-

criminating between the able poor and of apportioning

the degree of public provision to the degree of actual im-

potency.”14

In the same vein,an 1866 annual report from

the Massachusetts State Board of Charities asserted that

“it is better to separate and diffuse the dependent classes

than to congregate them,” while providing instructions

for a “system of observation” in which to “collect all the

valuable facts” necessary for classification.15

In Lowell,

politicians regularly made distinctions between the

“worthy poor” and their unworthy counterparts, fretting

for the “idlers” who took advantage of state provisions.

Mayor James B. Casey expressed, “the giving of aid […]

for Vocational Education, 1921).

12 United States Children's Bureau, Child Care and Child Welfare; Outlines for Study, 1921.

13 Massachusetts Legislative Committee, The Josiah Quincy Report of 1821 on the Pauper Laws of Massachu-

setts, Written for the Massachusetts Legislative Committee (Boston: Massachusetts Legislative Committee, 1821).

14 Massachusetts Legislative Committee, The Josiah Quincy Report of 1821 on the Pauper Laws of Massachu-

setts, Written for the Massachusetts Legislative Committee, 1821.

15 Massachusetts Board of State Charities, Second Annual Report, January 1866 (Boston: Massachusetts Board

of State Charities, 1866).

16 Hon. John F. Meehan, Inaugural Address to the Lowell City Council (Lowell: Buckland Publishing Company).

17 DavidWagner, Ordinary People: In and Out of Poverty in the Gilded Age (NewYork: Paradigm Publishers, 2008), 17, 28.

18 Massachusetts State Board of Lunacy and Charity, Twenty-Eighth Annual Report (Boston: Wright and Potter

Printing Co. State Printers, 1906).

19 William H. Slingerland, Child Welfare Work in California: A Study of Agencies and Institutions (New York: Spe-

cial Agent Department of Child-Helping, Russell Sage Foundation, 1916), 195.

20 Robert A. Davis, Mentality of Orphans (Boston: Gorham Press, 1930), 164, 198.

as an injury is not only worked upon the family, but to

the community as well.” The objective of the state board,

Casey emphasized, was to ensure that charity only went

to paupers with no potential of self-sufficiency. Methods

of differentiating care were contingent on the idea that

some paupers were intrinscally unworthy.16

This conception of poverty was the ideological

foundation of the orphanage. A resolution from the

Massachusetts Board of Charities in 1864 warned of

“the unfavorable influences of [adult paupers], which, if

a child be long subjected to them, will always haunt his

memory,” and surmised that reform was only possible

for children. By 1895, Massachusetts had become the

first state to switch to a foster-care system that placed

children into rural families; such a move was justified

by fears for the “contaminating influences”of “licentious

mothers.”17

Reiterated in 1906, the Massachusetts State

Board of Charity and Lunacy pushed for “the separation

of the children at [the] institution from the more or less

contaminating influences of the adult inmates, most of

whom are from the lowest strata of life.” Adults coded

as “immoral” were disproportionately those from immi-

grant and working-class backgrounds.18

Anti-immigrant sentiment was not incidental to

welfare reform, but deeply integral to its design. In expli-

cit language, academic studies linked the “importation of

foreign laborers”to “dependency among adults and child-

ren,”and asserted as fact that “low class laborers,generally

of foreign birth or descent” have “menac[ing]” children.19

A professor from the University of Colorado warned of

both the“army of immigrants”and“army of human energy

among the ranks of the orphan population.” A “clear line

of demarcation,”he suggested,was the only solution to this

problem.20

The psychologist G. Stanley Hall remarked in

1916 that “from the standpoint of eugenic evolution alone

VOLUME XI ISSUE I SPRING 2021

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yhrspring2021-211020115003/85/YHR-Spring-2021-10-320.jpg)

![considered, [certain immigrant groups] are mostly fit for

extermination in the interests of the progress of the race,”

and was quoted in a study by the Russell Sage Foundation

on orphan children.21

Echoed in governmental reports,of-

ficials expressed that immorality was “inherited,” and as-

sessed that “vice and crime” were “forced upon [orphans]

by those whose blood courses in their veins.” Definitions

of worthy and unworthy paupers, upon which hinged the

creation of entire governmental entities, were steeped in

white supremacist convictions.22

To this point, a committee formed in 1851 entitled

the Massachusetts Board of Commissioners in Relation to

Alien Passengers and State Paupers conflated the threat of

homeless paupers with immigrant residents.The intention

of this organization was to “ascertain the names of all forei-

21 Slingerland, Child Welfare Work in California, 38.

22 Massachusetts Senate, Report of Committee on Public Charitable Institutions on Visits to Several Public Chari-

table Institutions Receiving Patronage of the State, no. 79, (Boston: Massachusetts Senate, 1851).

23 Massachusetts General Court, An Act to Appoint a Board of Commissioners in Relation to Alien Passengers and

State Paupers, May 24, 1851, chap. 347, (Boston: Massachusetts General Court, 1851).

24 Massachusetts General Court, An Act in Relation to Paupers Having No Settlement in This Commonwealth,

May 20, 1852, chap. 275, (Boston: Massachusetts General Court, 1852).

25 New York Board of State Charities, Twenty-first Annual Report of the New York State Board of Charities: Special

Report of the Standing Committee on the Insane in the Matter of the Investigation of the New York City Asylum for the

Insane (New York: New York Board of State Charities, 1887); Massachusetts Commissioner of Mental Diseases, Annu-

al Report of the Massachusetts Commissioner of Mental Diseases for the Year Ending November 20, 1924: Report of

Director of Social Service (Boston: Massachusetts Commissioner of Mental Diseases, 1924).

gners [...] and also procure all such further information in

relation to age,etc.[...] in order to identify them in case they

should hereafter become a public charge.”23

Following suit,

1852 witnessed the criminalization of vagrant paupers and

systemic deportations of the homeless; no less than 7,005

paupers were deported from Massachusetts between 1870

and 1878.24

Adjacent to welfare,the expansion of a diagnos-

tic apparatus saw to the practice of psychiatric evaluations

andthecollectionofpersonaldatainasylumsandprisons—

not dissimilar from processes for pauper classification and

the record-keeping of vagrants.The carceral state was for-

med in tandem with welfare.25

Amid these national trends, Lowell in the early

20th century operated as a self-contained welfare ap-

paratus. In the years leading up to the federalization of

Beds for children in the interior of orphanage, unknown date. [3]

6

THE FRANCO-AMERICAN ORPHANAGE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yhrspring2021-211020115003/85/YHR-Spring-2021-11-320.jpg)

![welfare in the New Deal, Lowell assumed responsibility

for impoverished children and adults within its boun-

daries. In 1901, for example, the city invested a total of

$46,791.45 in relief, including expenses for ambulances,

food, medicine, surgeons, and coffins.26

The following

year, Lowell allocated $4,605.21 for the support of 98

orphans. Expenditures for dependent children ranged

between $1.25 (per orphan, per week) at St. Peter’s Or-

phan Asylum and $7.00 (per orphan, per week) at the

Children’s Hospital in Boston. Interestingly, Lowell’s

charitable budget made accommodations “on account of

Lowell’s paupers residing [elsewhere],” with payments

totaling $68.28 to Beverly, $482.25 to Lawrence, and

$542.28 to Boston in the year 1902.27

This system of lo-

calized responsibility can be understood as incentivizing

the tracking and policing of paupers, particularly with

programs geared toward behavior modification. In this

way, the framework for Massachusetts’ state welfare sys-

tem predated the “big bang” of Roosevelt’s New Deal

and was initially a localized process.

Contradiction was built into the DNA of Mas-

sachusetts welfare from the beginning.The fundamental

tenets of welfare—in which poverty was both a chari-

table cause and a moral failing to be discouraged—were

locked in existential conflict. As Michael Katz (1984)

has explained in his research on almshouses:

Built into the foundation of the almshouse were irre-

concilable contradictions.The almshouse was to be at once

a refuge for the helpless and a deterrent to the able-bo-

died. It was to care for the poor humanely and to dis-

courage them from applying for relief. In the end, one of

these poles would have to prevail.28

Development of the welfare state was shaped

by conflicting and discriminatory conceptions of care.

Demographic anxiety underpinned moves toward cen-

tralization and classification. Specialized institutions of

rehabilitation replaced generalized institutions of relief

26 Lowell City Council, Auditor's Sixty-Sixth Annual Report of the Receipts and Expenditures of the City of Lowell,

Massachusetts. Together with the Treasurer’s Account and the Account of the Commissioners of Sinking Funds for the

Financial Year Ending December 31, 1901 (Lowell: Buckland Publishing Company, 1901).

27 In turn, Lowell received funding from neighboring municipalities for their claimed paupers. Lowell City

Council, Report of the Secretary of the Overseers of the Poor for Lowell, January 1, 1902 (Lowell: Buckland Publishing

Company, 1902), 24.

28 Michael B. Katz, "Poorhouses and the Origins of the Public Old Age Home," in The Milbank Memorial Fund

Quarterly. Health and Society (Hoboken: Wiley, 1984), 118.

29 David Vermette, A Distinct Alien Race: The Untold Story of Franco-Americans, Industrialization, Immigration,

and Religious Strife (Montreal: Baraka Books, 2018), 98-111.

in order to omit care to low-income, non-native popula-

tions.As a result,immigrants in Lowell relied upon their

own community networks to build systems of assistance.

HE INTERRELATION OF industry and

immigration remains key to understanding

the economic context for French-Cana-

dians in Lowell. As early as the 1840s, mill

recruiters scoured depressed areas of Quebec for inex-

pensive labor, attracting wage-earners with the promise

of opportunity and personal betterment.A ten-day strike

following the reopening of Lowell mills after the Ci-

vil War further accelerated recruitment in Canada. By

1900, 24% of all cotton mill workers nationwide were

French-Canadian New Englanders;workers with at least

one French-Canadian parent comprised 44% of textile

operatives at this time.29

The dimensions of French-Ca-

nadian identity in the U.S. were, from the beginning,

economic in addition to cultural.In a presentation to the

Massachusetts Bureau of Labor Statistics, the editor of

the newspaper Le Travailleur elucidated this connection:

The Canadians are peaceful, law-abiding citizens; and

they accept the wages fixed by the liberality, or sometimes

the cupidity and avarice, of the manufacturers. […] Ca-

nadians have been great factors in the prosperity of ma-

nufacturing interests. Steady workers and skilful [sic],

the manufacturers have benefited by their condition of

THE FINEST

MILLS AND THE

DIRTIEST STREETS

Economic Context of

the Orphanage

T

VOLUME XI ISSUE I SPRING 2021

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yhrspring2021-211020115003/85/YHR-Spring-2021-12-320.jpg)

![poverty to reduce wages and compete favorably with the

industries of the Old World.30

Upon arrival to Lowell,French Canadians faced

deteriorating working conditions, living conditions,

and nativist backlash. Public officials who referred to

French-Canadians struck a careful balance between

demonization and appreciation of their contributions.

Simultaneously, immigrants were a “horde of indus-

trial invaders” and “indefatigable workers” supporting

the city’s most lucrative industries. Condemnation and

exploitation were not opposing forces but two sides of

the same coin. David Vermette (2018) demonstrates

that the degradation of industrial conditions coincided

with the shift from Yankee women to immigrants as

the principal source of labor in Lowell.The defamation

of French Canadians, such that they were referred to as

“sordid” and “an inferior race,” was both symptomatic

of and justification for the inhumane environment in

which they lived.31

Vermette explains,

It was the othering of the distinct, alien races in the mills

that made possible this dehumanization, the identifi-

cation of human beings with interchangeable machine

parts. Care and empathy extended to those within the

tribe and French-speaking Catholics of Quebec were not

members of the Yankee tribe.32

Downstream, poverty wages and the retrac-

tion of mill-subsidized housing had created a health

crisis. In 1882, the Lowell Board of Health reported

that the French-Canadian neighborhoods of Little Ca-

nada were an “unwholesome quarters” where “sanitary

30 Le Travailleur was a French-Canadian newspaper based in Worcester, Massachusetts. Massachusetts Bureau

of Statistics of Labor, "Resolve Relative to a Uniform System of Laws in Certain States Regulating the Hours of La-

bor," in Thirteenth Annual Report of the Massachusetts Bureau of Labor Statistics, chap. 29 (Boston: Massachusetts

Bureau of Statistics of Labor).

31 DavidVermette, A Distinct Alien Race, 207, 250. Notably, the degradation of working conditions at this time coincided

with an overall increasing population of immigrants in Lowell. Statistics compiled by the Lowell Board ofTrade report that 40%

of the city’s population circa 1916 was native born.The remaining 80% of residents were of either foreign or mixed heritage.

Lowell Board ofTrade, Digest of the City of Lowell and its SurroundingTowns (Lowell: Lowell Board ofTrade, 1916), 5.

32 Lowell Board of Trade, Digest of the City of Lowell and its Surrounding Towns, 116.

33 George Frederick Kenngott, The Record of a City: A Social Survey of Lowell, Massachusetts (New York: Mac-

millan Company, 1912), 68-71.

34 Yukari Takai, Gendered Passages: French-Canadian Migration to Lowell, Massachusetts, 1900-1920 (New

York: Peter Lang Publications, 2008), 50.

35 Statistics calculated from survey data. Children's ages ranged between 1 and 5. G. Frederick Kenngott, The

Record of a City: A Social Survey of Lowell, Massachusetts (New York: Macmillan Company, 1912), 68-71, 133-34.

36 Frederick Kenngott, The Record of a City: A Social Survey of Lowell, Massachusetts, 108.

37 Alfred Laliberté, "L’école paroissiale," in [Rev. Adrien Verette] La Croisade Franco-Americaine (Manchester,

laws [were] grossly violated. As a result, “many of these

innocents [have] died from lack of nourishment, care,

cleanliness, and pure air.”33

Two years prior, the Lowell

Daily Citizen described the city as having “the finest

mills and the dirtiest streets," marked by foul odors

and animal matter. In 1881, a physician visiting Litt-

le Canada found “the family and borders in such close

quarters, that the two younger children had to be put to

bed in the kitchen sinks.”34

At this time, Lowell’s Little

Canada constituted the second densest neighborhood

in the country after Ward 4 of New York City.The pre-

carity that French-Canadian immigrants experienced

was most evident in their heightened mortality rates;

between 1890 and 1909 the likelihood of French-Ca-

nadian children passing away before the age of 5 ranged

from 14% to 18% compared to 3% for native children.

In 1890, adult French-Canadians experienced more

than double the 15% mortality rate of their non-immi-

grant counterparts. The stakes for mutual aid societies

in Lowell were demonstrably high.35

Shared culture was the foundation for facilitating

intra-community relief in Lowell. By 1880, French-Cana-

dians in New England had founded 63 parishes, 73 natio-

nal societies, and 37 French-language newspapers, often

directly and indirectly involved with charitable causes. By

1908, 133 parochial schools attending to 55,000 students

had been instituted.36

As the artist Alfred Laliberté has ar-

ticulated:“the parish school remains the cornerstone of our

national survivance in the United States.We can have pari-

shes,societies,newspapers,and efforts of all kinds,but if our

children do not attend parochial schools, we [will] lose all

that.”Survival was a matter both literal and cultural.37

8

THE FRANCO-AMERRICAN ORPHANAGE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yhrspring2021-211020115003/85/YHR-Spring-2021-13-320.jpg)

![Interestingly, Little Canada was an enclave no-

table for its French-Canadian roots and internal de-

mographic diversity. Yukari Takai (2008) finds that the

neighborhoods attracted workers of various backgrounds;

a former resident recalled, “Everyone spoke French, in-

cluding several families with names such as O’Beirne,

O’Flahavan,Moore,Murtagh,Thompson,O’Brien,Lord,

Sawyer, Thurber, Sigman, Tumas, Protopapas, Brady,

and Grady.”38

It is this complexity—that the city was a

place where immigrants could affirm their identities, be

absorbed into other identities, and one where cultural he-

terogeneity was celebrated among the workers—which

offers a glimpse of a multicultural ideal specific to Lowell.

Before instituting the FAO, the Grey Nuns were certain

to include the clause: “while the orphanage is essentially

Franco-American,we will not exclude other nationalities.”

Children from Italian,Irish,and Syrian backgrounds were

accepted throughout the subsequent decades.39

Indeed,

the development of the FAO as a mutual aid organization

was in many ways the mirror inverse of restructuring that

occurred at the state level.The orphanage was established

to be specifically French-Canadian and later expanded to

cater for a more general, diverse population; Massachu-

setts policymakers, on the other hand, worked to restrict

access to more specific and narrowly defined categories of

paupers.American relief,in this way,has historically been a

site of contestation and contradiction.The FAO may have

been the pride of French-Canadians, but it was also a re-

source made deliberately available to anyone who needed it.

N.H.: L’Avenir National, 1938), 256.

38 This was likely because of Little Canada's proximity to local mills. Takai, Gendered Passages, 55.

39 "Correspondence of Grey Nuns 1908" Box 1 in Franco-American Orphanage/School collection at the Center

for Lowell History; "Admission records," Box 4 of Franco-American Orphanage/School collection at the Center for

Lowell History.

40 "Compter de l’Année," Box 3 Franco-American Orphanage/School collection, Center for Lowell History.

41 The FAO remained at full occupancy every year between 1908 and 1932. There was an expansion of the or-

phanage's facilities in 1913 that can account for a surge in orphans cared for by the FAO. This coincided with both a

deadly pandemic and the first world war; Statistics calculated by author from admission records 1908-1932. "Admission

Records," Box 4 Franco-American Orphanage/School collection, Center for Lowell History.

42 To further the conversation on industrialization and immigration as interrelated processes, it is worth noting

HE FAO CAN be conceptualized as both

a mutual aid society and an agency opera-

ting on behalf of the emerging welfare state.

As early as 1910, the FAO received funding

from the Massachusetts Bureau of Charity that ranged

between $300 and $700 annually and amounted to ap-

proximately 1-2% of the orphanage’s income. Between

50-80% of the institution’s revenue was derived from

“child’s pensions”paid by the orphans’families. Payment

varied according to means; of the 291 children in 1920,

188 paid $3 per week,84 paid $2.25,and 19 paid nothing.

As stipulated in the Grey Nuns’contract,“if an unknown

orphan is admitted to the orphanage, Monsieur le Curé

of [St. Joseph’s] parish would pay his pension […] to be

reimbursed by the parishioners.” Contributions through

Oeuvre du Pain,the fundraising initiative,peaked in 1923

at $5,567.12 and dropped to an all-time low of $99.55 in

1933.40

Orphan families, the French-Canadian commu-

nity,and the state of Massachusetts account for the FAO’s

survival at a time of economic recession and depression.

The term “charity”ascribed to the orphanage understates

both its proximity to the state and the contributions of

ordinary people to its success.

A statistical analysis of the FAO’s admission

records dating 1908 to 1932 further illuminates the

institution’s role in the community. Information inclu-

ding the orphan’s birthday, parental occupations, home

address, ethnicity, date of entry, and date of departure

was dutifully recorded by the Grey Nuns when avai-

lable.41

As depicted in Figure 1.1, most orphans had

French-Canadian heritage despite minor diversification

in the 1920s. Between 1908 and 1920, a considerable

97% of orphans were French-Canadian compared to

85% between 1920 and 1932. Figure 2.1 examines the

representation of orphans from industrial cities, with

exactly 69.7% from Lowell and the remainder with ties

to Lawrence and Haverhill. In total, 94% of children

were born in Massachusetts.42

ORPHANS WERE

NOT PARENTLESS

Inside the Franco-American

Orphanage

T

VOLUME XI ISSUE I SPRING 2021

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yhrspring2021-211020115003/85/YHR-Spring-2021-14-320.jpg)

![Demonstrated in Figure 3.1, the plurality of

parental occupations for children at the FAO were mill

workers and journaliers (“day workers”). Most interes-

tingly, the 3% of orphans with “none”parents—including

those listed as “dead,” “unknown,” or “unemployed”—re-

veals that 97% of orphans, the overwhelming majority,

had living and working parents.43

The documented du-

rations-of-stay for orphans at the FAO, depicted in Fi-

gures 4.1 and 4.2, bolster this discovery. Between 1908

and 1932, over half—55%—of children were dropped off

and picked up within the span of a year. Approximately

78% of orphans resided at the FAO for less than 3 years.

The average length of stay was 21 months compared to

the median of 9 months. Most orphans at the FAO (a)

had living,working parents,(b) were financially supported

by their families, and (c) returned to their families after a

temporary leave. This is a reconceptualization of what it

meant to be an orphan in the early 20th century.44

In the case of a Syrian workman,George Alias,a

decision was made to keep his son Philippe and daugh-

ter Eva at the orphanage for 22 days. Edmund Pinard,

a carpenter in a nearby neighborhood, dropped off and

picked up his son Joseph three times between 1926 and

1931. The three sons of Emile and Rose Duchanne, si-

milarly, stayed for a two month stretch in 1930 and for

a four-month stretch the same year. Parents, it is clear,

were not abandoning their children. The FAO provided

a service for surviving industrial life.45

HE FAO IN Lowell was an organization

inseparable from its industrial context.

This paper’s discovery that orphans were

supported by families and given tempora-

ry reprieve at the institution can reconceptualize the

that the mill cities of Haverhill, Fall River, Lawrence, and Lynn were locations with large immigrant populations; "Admis-

sion Records," Box 4 Franco-American Orphanage/School collection, Center for Lowell History.

43 Journaliers worked primarily in seasonal and temporary job. Additionally, between 1908 and 1932, only 22

children were placed into adoptive care. This was primarily to other family members. "Admission Records," Box 4 Fran-

co-American Orphanage/School collection, Center for Lowell History.

44 "Admission Records," Box 4 Franco-American Orphanage/School collection, Center for Lowell History.

45 "Admission Records," Box 4 Franco-American Orphanage/School collection, Center for Lowell History.

46 C.L., "Little Canada," oral interview, May 3, 1975, typewritten transcript. Center for Lowell History, French-Ca-

nadian Oral Histories, 5, 22.

47 Richard Santerre, La Paroisse Saint-Jean-Baptiste et les Franco-Americains de Lowell, Massachusetts, 1868-

1968 (Manchester, N.H.: Editions Lafayette, 1993), 43-44.

meaning of early 20th century charity. The FAO is

analogous to contemporary systems of mutual aid and

can demonstrate the indirect, localized mechanisms

by which the Massachusetts state distributed relief.

The myth of orphanages as repositories for abandoned

children remains an outdated stigmatization of wor-

king-class parents; indeed, this paper outlines the

ways in which orphanages were resources created by

neighborhoods in collaboration with each other. Fur-

thermore, the centrality of immigrant identity—both

as the framework for organizing within working com-

munities and as a site of backlash by nativist intel-

lectuals—to the development of American welfare is

posited to be a significant dimension of analysis and

one that merits future research.

The FAO is proof of the interdependent rela-

tionships that defined the French-Canadian community

in Lowell.As has been articulated by a former resident of

Lowell’s Little Canada:

The Population was so big in Little Canada that the

blocks were real[ly] close. But all families got along beau-

tiful[ly] and we were all French people. […] Everybo-

dy helped everybody, which is not done nowadays like it

was then, but people that had the money—if one needed

help that means they would get together and they would

come over and help. [...] If you look back to it, I still think

I’d like to be there.46

The FAO demonstrates the self-determination

of French-Canadians within a context of structural

inequality. As Richard Santerre (1993) has put into

words, “people found emotional sustenance, psycho-

logical security, and a sense of meaning in Little Ca-

nada of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.” This

meaning and security was built from the bottom up by

working families.47

CONCLUSION

T

10

THE FRANCO-AMERICAN ORPHANAGE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yhrspring2021-211020115003/85/YHR-Spring-2021-15-320.jpg)

![Figure 1.1 Orphan Ethnicities

1908-1912 1913-1917 1918-1922 1923-1927 1928-1932 % Overall

384 1010 703 550 473 96.0% Fr. Canadian

0 11 10 11 20 1.6% Irish

0 0 3 35 10 1.4% American

0 15 15 59 33 0.1% Italian

4 17 6 76 63 3.9% Other

The “Other” category represents the small number of Syrian and Belgian children at the orphanage. [5]

Figure 2.1 Top City Origins of Orphans

1908-1912 1913-1917 1918-1922 1923-1927 1928-1932 % Overall

277 627 634 404 311 69.7% Lowell

11 93 4 19 15 4.4% Lawrence

14 24 12 47 10 3.3% Haverhill

1 13 4 31 57 3.3% Salem

4 43 12 8 33 3.1% Lynn

8 6 5 22 7 1.5% Boston

[6]

Figure 3.1 Top Parental Occupations of Orphans

1908-1912 1913-1917 1918-1922 1923-1927 1928-1932 % Overall

136 249 109 142 106 36.1% Mill workers

121 189 75 42 72 24.2% Day workers

16 57 37 22 24 7.6% Machinists

22 24 23 31 16 5.6% Carpenters

8 33 11 32 16 4.9% Shoemakers

8 21 6 12 18 3.2% Painters

0 21 7 9 27 3.1% Clerks

2 7 6 21 5 2.0% Metalsmiths

1 5 3 12 18 1.9% Drivers

13 2 3 23 25 3.2% None

“Day Workers” consisted of seasonal and temporary laborers, primarily working in mills, construction, and

agriculture. The “None” category signifies the number of parents designated as “absent,” “unemployed,”

“sick,” “deceased,” or "handicapped." Note: not all parental occupations are represented on the table. Other

professions include electricians, grocers, farmers, bakers, barbers, and plumbers. [7]

VOLUME XI ISSUE I SPRING 2021

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yhrspring2021-211020115003/85/YHR-Spring-2021-16-320.jpg)

![Figure 4.1 Length of Stay at Orphanages (Percentages)

1908-1912 1913-1917 1918-1922 1923-1927 1928-1932 Total

5.2% 14.9% 13.8% 8% 8.9% 10.6% 5+ years

0.6% 8.6% 18.5% 10.3% 14.9% 11.6% 3-5 years

21.4% 4.8% 32.5% 24.5% 28.1% 22.7% 1-3 years

14.5% 8.3% 11.8% 18.7% 14.5% 13.7% 6-12 months

17.9% 14.3% 6.3% 15.7% 12.3% 12.7% 3-6 months

41% 49.5% 17.5% 23% 21.7% 28.6% <3 months

[8]

Figure 4.2 Length of Stay at Orphanage (Mean and Median)

1908-1912 1913-1917 1918-1922 1923-1927 1928-1932 Total

11.2 20.4 28.4 19.7 21.6 21.4 Mean

3 3 21 9 12 9 Median

Units in months. [9]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

C.L., “Little Canada,” Oral interview, May 3, 1975,

typewritten transcript. Center for Lowell History,

French-Canadian Oral Histories.

Casey, Hon. James B. 1906. Inaugural Address of His

Honor to the City Council. Lowell: Buckland Pub-

lishing Company. Hathitrust.org.

Crenson,Matthew A.and Peter Fritzsche.Building the

Invisible Orphanage: A Prehistory of the American Wel-

fare System.Boston: Harvard University Press,1998.

Davis, Robert A. Mentality of Orphans. Boston: Gor-

ham Press, 1930. Hathitrust.org.

Franco-American Orphanage. Admissions Records.

Center for Lowell History, Franco-American

Orphanage/School Collection Box 4.

Franco-American Orphanage. “Compter de l’Année.”

Center for Lowell History, Franco-American

Orphanage/School Collection Box 3.

Franco-American Orphanage. “Franco-American

Orphanage Housed in Famous Old Home.” Un-

identified Newspaper Clipping. Center for Low-

ell History, Franco-American Orphanage/School

Collection Box 2.

Franco-American Orphanage.“Franco-American

Orphanage.”Center for Lowell History, Fran-

co-American Orphanage/School Collection Box 1.

Franco-American Orphanage.“Recorded Meetings of

the Members of the Executive Committee of the

Orphanage.”Center for Lowell History, Fran-

co-American Orphanage/School Collection Box 3.

Franco-American Orphanage. “Une Lettre par Sr.

Théodore, Septembre 1917.” Center for Lowell

History, Franco-American Orphanage/School

Collection Box 2.

Katz, Michael B. In the Shadow of the Poorhouse: The So-

cial History of Welfare in America. New York: Basic

Books, 1986.

Katz, Michael B. "Poorhouses and the Origins of the

Public Old Age Home." The Milbank Memori-

al Fund Quarterly. Health and Society 62, no. 1

(1984): 110-40. doi:10.2307/3349894.

Kenngott, G. Frederick. The record of a city: a social sur-

vey of Lowell, Massachusetts. New York: Macmillan

Company, 1912. Hathitrust.org.

Kleinberg, S. J. Widows and Orphans First: The Fami-

ly Economy and Social Welfare Policy, 1880-1939.

Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

Kropotkin, Peter. Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution.

London: Heinemann, 1902. Reprint, Mineola,

New York: Dover Publications, 2012. Citations

refer to the Dover edition.

12

THE FRANCO-AMERICAN ORPHANAGE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yhrspring2021-211020115003/85/YHR-Spring-2021-17-320.jpg)

![Laliberté, Alfred. “L’ecole paroissiale,” in [Rev. Adrien

Verette] La Croisade Franco-Americaine. Man-

chester, N.H.: L’Avenir National, 1938.

Lowell Board of Charities. 1908. “Financial State-

ment of Charity Department for Year 1908,”

Annual Report of the Superintendent for the State

Charities. Lowell: Buckland Publishing Compa-

ny. Hathitrust.org.

Lowell Board of Charities. 1910. “Financial State-

ment of Charity Department for Year 1910,”

Annual Report of the Superintendent for the State

Charities. Lowell: Buckland Publishing Compa-

ny. Hathitrust.org.

Lowell Board of Trade. 1916. Digest of the City of Low-

ell and its Surrounding Towns, published August

1, 1916, by the Executive Committee of the Lowell

Board of Trade. Lowell: Lowell Board of Trade.

Hathitrust.org.

Lowell City Council. 1901. Auditor’s Sixty-Sixth

Annual Report of the Receipts and Expenditures of

the City of Lowell, Massachusetts. Together with

the Treasurer’s Account and the Account of the Com-

missioners of Sinking Funds for the Financial Year

Ending December 31, 1901. Lowell: Buckland

Publishing Company. Hathitrust.org.

Lowell City Council. 1902. Municipal Register Con-

taining Rules and Orders of the City Council and a

List of the Government and Officers of the City of

Lowell. Lowell: Buckland Publishing Company.

Hathitrust.org.

Lowell City Council. 1910. Municipal Register Con-

taining Rules and Orders of the City Council and a

List of the Government and Officers of the City of

Lowell. Lowell: Buckland Publishing Company.

Hathitrust.org.

Lowell City Council. 1902. Report of the Secretary

of the Overseers of the Poor for Lowell, January 1,

1902. Lowell: Buckland Publishing Company.

Hathitrust.org.

Massachusetts Board of State Charities. 1866. Second

Annual Report, January 1866. Boston: Massachu-

setts Board of State Charities. Hathitrust.org.

Massachusetts Board of State Charities. 1914. Argu-

ments Presented March 12, 1914 by the Massachu-

setts State Board of Charity Through its Secretary,

Robert W. Kelso, to the Legislative Committee

Against Proposals of the Massachusetts Commission

on Economy and Efficiency, Senate Document 440.

Boston: Massachusetts State Board of Charities.

Hathitrust.org.

Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of Labor. 1880.

“Resolve Relative to a Uniform System of Laws

in Certain States Regulating the Hours of Labor,”

Thirteenth Annual Report of the Massachusetts Bureau

of Labor Statistics, chap. 29. Hathitrust.org.

Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of Labor. 1881.

Resolutions Protesting Against Certain Portions of

Carrol D. Wright’s Annual Report of the Bureau of

Statistics. Boston: Massachusetts Bureau of Statis-

tics of Labor. Hathitrust.org.

Massachusetts Child Council. 1939. Juvenile Delin-

quency in Massachusetts as a Public Responsibility;

An Examination into the Present Methods of Deal-

ing with Child Behavior, its Legal Background and

the Indicated Steps for Greater Adequacy. Boston:

Massachusetts Child Council. Hathitrust.org.

Massachusetts Child Labor Committee. 1910.

“Child Labor in Massachusetts.” Annual Report

of the Massachusetts Child Labor Committee. Bos-

ton: Massachusetts Child Labor Committee.

Hathitrust.org.

Massachusetts Child Labor Committee. 1912.

“Child Labor in Massachusetts,” Annual Report

of the Massachusetts Child Labor Committee. Bos-

ton: Massachusetts Child Labor Committee.

Hathitrust.org.

Massachusetts Child Labor Committee. 1921. Hand-

book of Constructive Child Labor Reform in Mas-

sachusetts. Boston: Massachusetts Child Labor

Committee. Hathitrust.org.

Massachusetts Commissioner of Mental Diseases.

1924. Annual Report of the Massachusetts Com-

missioner of Mental Diseases for the Year Ending

November 20, 1924: Report of Director of Social

Service. Boston: Massachusetts Commissioner of

Mental Diseases. Hathitrust.org.

Massachusetts General Court. 1851. An Act to Ap-

point a Board of Commissioners in Relation to

Alien Passengers and State Paupers, May 24, 1851,

chap. 347. Boston: Massachusetts GeneraL

Court. Hathitrust.org.

Massachusetts General Court. 1852. An Act in Re-

lation to Paupers Having No Settlement in This

Commonwealth, May 20, 1852, chap. 275. Boston:

Massachusetts General Court. Hathitrust.org.

VOLUME XI ISSUE I SPRING 2021

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yhrspring2021-211020115003/85/YHR-Spring-2021-18-320.jpg)

![Image and Figure Sources

Massachusetts Legislative Committee. 1821. The Josiah

Quincy Report of 1821 on the Pauper Laws of Mas-

sachusetts, Written for the Massachusetts Legislative

Committee. Boston: Massachusetts Legislative

Committee. Hathitrust.org.

Massachusetts Prison Commissioners. 1901. First

Annual Report. Boston: Massachusetts Prison

Commissioners. Hathitrust.org

Massachusetts Senate. 1850. Report of Committee on

Public Charitable Institutions on Visits to Several

Public Charitable Institutions Receiving Patronage

of the State, no. 79. Boston: Massachusetts Sen-

ate. Hathitrust.org.

Massachusetts Senate. 1858. Report of the Joint Stand-

ing Committee on Public Charitable Institutions as

to Whether Any Reduction Can be Made in Ex-

penditures for the Support of State Paupers, no. 63.

Boston: Massachusetts Senate. Hathitrust.org.

Massachusetts State Board of Lunacy and Charity.

1906. Twenty-Eighth Annual Report. Boston:

Wright and Potter Printing Co. State Printers.

Hathitrust.org.

Massachusetts State Board of Lunacy and Charity.

1919. Forty-First Annual Report. Boston: Wright

and Potter Printing Co. State Printers. Hathi-

trust.org.

Massachusetts State Charities. 1859. Report of the

Special Joint Committee Appointed to Investigate the

Whole System of the Public Charitable Institutions

of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, during the

Recess of the Legislature in 1858: Massachusetts Sen-

ate Document No.2. Boston: Massachusetts State

Charities. Hathitrust.org.

Meehan, Hon. John F. 1905. Inaugural Address to the

Lowell City Council. Lowell: Buckland Publishing

Company. Hathitrust.org.

Mohr, John W., and Vincent Duquenne. "The Duality

of Culture and Practice: Poverty Relief in New

York City, 1888-1917." Theory and Society 26, no.

2/3 (1997): 305-56. www.jstor.org/stable/657930.

New York Board of State Charities, Twenty-first An-

nual Report of the New York State Board of Chari-

ties: Special Report of the Standing Committee on the

Insane in the Matter of the Investigation of the New

York City Asylum for the Insane. New York: New

York Board of State Charities, 1887.

Phelps, Edward Bunnell. “Infant Mortality and

Its Relation to the Employment of Mothers.”

Washington: Government Printing Office, 1912.

Hathitrust.org.

Ramey, Jessie. Child Care in Black and White: Working

Parents and the History of Orphanages. Chicago:

University of Illinois Press, 2012.

Slingerland, William H. Child Welfare Work in Califor-

nia: A Study of Agencies and Institutions. Concord:

The Rumford Press, 1916. Hathitrust.org.

Takai, Yukari. Gendered Passages: French-Canadian Mi-

gration to Lowell, Massachusetts, 1900-1920. New

York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc, 2008.

United States Children’s Bureau. “Child Care and

Child Welfare; Outlines for Study.”Washington:

Federal Board for Vocational Education, 1921.

Hathitrust.org.

Vermette, David. A Distinct Alien Race: The Untold

Story of Franco-Americans. Montreal: Baraka

Books, 2018.

Wagner,David.Ordinary People:In and Out of Poverty in

the Gilded Age.New York: Paradigm Publishers,2008

Wolfe, Alan. The Limits of Legitimacy: Political Con-

tradictions of Contemporary Capitalism. New York:

Free Press, 1977.

[1] Box 12 of Franco-American Orphanage/School

collection, Center for Lowell History.

[2] Box 12 of Franco-American Orphanage/School

collection, Center for Lowell History.

[3] Box 4 of Franco-American Orphanage/School

collection, Center for Lowell History.

[4] Box 4 of Franco-American Orphanage/School

collection, Center for Lowell History.

[5] Box 4 of Franco-American Orphanage/School

collection, Center for Lowell History.

[6] Box 4 of Franco-American Orphanage/School

collection, Center for Lowell History.

[7] Box 4 of Franco-American Orphanage/School

collection, Center for Lowell History.

[8] Box 12 of Franco-American Orphanage/School

collection, Center for Lowell History.

[9] Box 12 of Franco-American Orphanage/School

collection, Center for Lowell History.

14

THE FRANCO-AMERICAN ORPHANAGE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yhrspring2021-211020115003/85/YHR-Spring-2021-19-320.jpg)

![SPRING 2021

TECHNOLOGY AND

PARADIGM

The X-Ray,Electrical Therapeutics,and the Consolidation of Biomedicine

by Libby Hoffenberg, Swarthmore College '20

Written for an interdisciplinary honors thesis in History and Philosophy of the Body

Advised by Professor Timothy Burke

Edited by Daniel Ma, Gabby Sevillano, and Katie Painter

An 1897 setup for taking an x-ray of the hand. [1]

VOLUME XI ISSUE I SPRING 2021

15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yhrspring2021-211020115003/85/YHR-Spring-2021-20-320.jpg)

![regular purification of the Economy.”17

Rivieré appeals

to discourses of chemistry, neurology, physiology, and

hormonal (“trophic”) functions to justify his therapeu-

tic method.These multiple discourses, as well as his des-

cription of the body as an “economy,” reveal the impulse

within the medical community to theorize health and

sickness as involving the equilibrium of the entire orga-

nism.Electricity provided a pivot from vague understan-

dings of the body based on the harmonization of its parts

to scientific medicine’s updated models of homeostasis

based on biochemical entities. Electricity connoted the

vital force that coordinated activity but was also distinc-

tly modern, a powerful tool with vast potential to know

the world in ever more precise ways.

17 D. J. Rivieré, Annals of Physico-Therapy (Paris: Physico-Therapeutic Institute of Paris, 1903).

18 Herbet Robarts, The American X-Ray Journal 1, no.1 (1899).

19 Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health "200 Years

of American Medicine (1776-1976)," an exhibit at the National Library of Medicine.

Electricity was an enticing cure for a medical com-

munity that was actively deliberating over the proper way

to treat sick bodies. The flexible ontologies underlying

electricity authorized its use as a therapeutic modality

in both allopathic and homeopathic practices. The de-

bate between allopathy and homeopathy as the most

appropriate medical system roughly mirrored the de-

bate between those who thought that diseases ought to

be cured by treatments administered externally from the

body and those who believed that the disease’s natural

course of development in the body would cure the pa-

tient. Allopathic practitioners sought different kinds of

substances to administer to the body, while homeopaths

supposed that the body naturally stored the entire phar-

macopeia of substances it could need. Allopaths tended

to celebrate the variety of pharmaceutical compounds

that were being synthesized or discovered with increasing

frequency. New therapies presented new tools to combat

disease. Homeopaths tended to criticize the search for

new compounds. Medical pamphlets and journals fea-

tured both drug advertisements and polemics,written by

and for doctors, against the use of drugs in medical care.

In this space of contradictory mindsets, electricity could

be configured as both external and internal; it was inte-

gral to the matter of the natural world but also existed

innately within the living body.

The x-ray’s continuity with electrical modalities

meant that its therapeutic potential could be justified

by appeals to vitality and energy. The x-ray’s association

with vitalism is evident in looking at the cover of the first

issue ofThe American X-Ray Journal.This journal began

in May 1897 with the stated intention “to give to its rea-

ders a faithful resume of all x-ray work.”18

The American

medical field saw an increase in the number of published

medical journals in the nineteenth century as physicians

returned from graduate training in Austria and Germany.

They grouped themselves into professional associations

and consolidated their reports of clinical and laborato-

ry research in medical publications.19

However, even as

x-ray practitioners began to coalesce around professional

organizations,they did not abandon the vitalistic conno-

tations of the x-ray. The cover of the first issue of The

American X-Ray Journal depicts a figure administering

the x-ray to the globe from outside the globe, indica-

The cover of the first issue of The American

X-Ray Journal. [2]

20

TECHNOLOGY AND PARADIGM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yhrspring2021-211020115003/85/YHR-Spring-2021-25-320.jpg)

![ting that the x-rays were seen to come from a mysterious,

non-earthbound, place. The spiritual connotations of a

figure floating above the earth connotes the idea of an

immaterial substance that animates the physical world,

flowing freely between living and non-living matter.

ISTORIANS HAVE NOTED the uti-

lity of the x-ray in consolidating the pro-

fessional authority of allopathic doctors

and radiological specialists—those in fields

that would later professionalize in relation to the x-ray’s

diagnostic capabilities.However,there has been conside-

rably less attention given to the way that non-allopathic

practitioners justified their authority through the x-ray,

often continuing to use the machine for non-diagnostic

purposes.After the x-ray had been wrangled as a specifi-

cally medical instrument,but before it became a standar-

dized diagnostic tool, various medical sects incorporated

the technology into their practices as a method of legiti-

mization. This period—approximately the first ten years

of the twentieth century—represents a middle space in

the x-ray’s early years that corresponds to the shifting

context of professional medicine.

Historians have noted practitioners’ self-legitima-

tion through the use of the x-ray, as the device came to

symbolize advanced scientific medicine. However, they

have not engaged with the particular nature of this sym-

bolism—the specific capacities that made the x-ray au-

thoritative. The invocation of the x-ray’s authority by

non-allopathic practitioners (those who would not go on

to coordinate their activities in relation to this authority)

shows that the regard given to the technology was not

solely a response to its association with the kind of scien-

tific biomedicine that would go on to dominate health-

20 "Electro-Therapeutics," Chicago Daily Tribune, July 23, 1899, 30.

21 Herbet Robarts, The American X-Ray Journal 1, no. 2 (1899), 30.

care. Rather, its authority was premised on its ability to

produce objective scientific images. Even when homeo-

pathic practitioners used the x-ray in therapeutic vitalis-

tic contexts,they legitimized their practice by recourse to

the x-ray’s privileged capacity for visualization.

After the x-ray had become widely known to the

general public,but before it attained its diagnostic role in

institutionalized biomedicine,it was seen as the most au-

thoritative form of electrical healing. An 1899 article in

the Chicago Daily Tribune chronicles the moment the

x-ray became a privileged electrical therapy. After ex-

pounding the various specialties in which electricity was

useful and effective “in the hands of a skilled physician”

—dentistry,medicine,surgery,cauterization,thermal and

chemical effects—the author laments the hindering of

the field’s development at the hands of “quackery prac-

ticed in early days.”20

The authority of “regular practitio-

ners,”he says,was threatened by individuals who peddled

products like electric belts and electric hairbrushes. The

author then suggests that legitimate practitioners, who

previously refrained from publicizing electrical therapies,

were becoming louder voices in the field.This “change in

public sentiment,”he suggests,“[is] greatly stimulated by

the discovery of the X ray by Baron Röntgen.” This ar-

ticle also affirms that the x-ray was not considered a dis-

tinctly new kind of machine. Articles in The American

X-Ray Journal even continued to refer to the x-rays as

“vibrations,” indicating the x-ray’s continued association

with a broader set of other electro-therapeutic machines.

An article in the same journal states that the x-ray had

“brought more forcibly before the minds of physicians

the value of the electric current as a therapeutic agent.”21

The x-ray, then, was beneficial not only in consolidating

the authority of scientific medicine, but also in justifying

the continued use of electrical therapeutics.

The x-ray, out of all other electrical therapies, be-

came associated with advanced scientific medicine be-

cause it was the only electrical therapy that produced

an image. The x-ray’s image-making capacity makes it a

case study for the history of modern scientific medicine’s

self-legitimation through the technique of specialized

perception. In the eighteenth century, the epistemically

authoritative gaze helped to standardize the interpreta-

tion of the body’s interior, so that medical professionals

could amass a stable body of knowledge about anato-

H

MECHANICAL

OBJECTIVITY

AND THE

DOCTOR-PATIENT

RELATIONSHIP

VOLUME XI ISSUE I SPRING 2021

21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yhrspring2021-211020115003/85/YHR-Spring-2021-26-320.jpg)

![increasingly prevalent mandate to maintain individual

health—an imperative that called for continual dis-

cernment of the hidden structures and mechanisms of

the body. The category of diagnosis was useful in subs-

tantiating a paradigm wherein the patient sought not

an immediate cure but information with which to make

decisions about long-term health.

Although the x-ray was just one piece of tech-

nology within a complex healthcare system, and the

physical presence of the machine itself was diminished,

the aesthetic of the technology remained significant.

In the years after World War I, the x-ray symbolized

not only modern scientific visuality, but modern indus-

trial machinery generally. Radiologists appealed to the

x-ray’s aura of technological sophistication to justify

their role in hospital systems as qualified professionals.

In the hospital’s integration of multiple medical prac-

tices into a single system, there was sometimes tension

between radiology departments and the demands of

a large business-oriented hospital. A 1934 article pu-

blished in Radiology, a professional journal started in

1929, identified a “peculiar relationship between hospi-

tal and roentgenologists,” in which the hospital owned

the equipment and facilities that the radiologist used,

but the radiologist performed services that he/she saw

as involving distinct technical expertise. Hospitals,

on the other hand, believed that they could produce

“roentgenograms” without the help of the radiologist

and that the radiologist simply provided interpretation

of the images. This discrepancy resulted in confusion

over how to divide compensation between the hospital

and the radiologist.39

A 1935 article in the same journal

lamented that “many physicians consider the roentge-

nologist a mere photographer.”40

The “domestication” of the x-ray machine from

a cumbersome instrument to a modern and efficient

technology embedded in the hospital threatened the

radiologist because he or she could no longer demons-

trate the miraculous powers of the x-ray. Previously the

side effects, even when they were unpleasant or fatal,

proved that the x-ray was working. One radiologist in

39 Leon Menville and Howard Doub, "The X-ray Problem and a Solution: A Discussion of the Proposed Separation

of the X-ray Examination into Technical and Professional Portions," in Radiology 23, no.5 (Oak Brook, Illinois: The Radio-

logical Society of North America, 1934).

40 Emmet Keating, "Fee Tables and the Roentgenologists," in Radiology 24, no. 3 (Oak Brook, Illinois: The Radiolo-

gy Society of North America, 1935).

41 Lavine, "The Early Clinical X-Ray in the United States," 612.

42 Hessenbruch, "Calibration and Work in the X-Ray Economy," 414.

the gas tube era noted that he even “ma[de] it a point

in every case to produce a burn,” as the visible effects

of the rays indicated its curative efficacy.41

Radiologists

after WWI, on the other hand, did not attempt to pro-

duce visible effects, nor was the public nearly as willing

to tolerate them.Instead,they fashioned their authority

as technicians who provided the service of interpreting

information produced by sophisticated machines. They

claimed their professional status in reference not to the

patient’s body as a site of visible effects but to the x-ray

machine itself and its ability to produce diagnostic in-

formation. The radiologist modified the role that was

vacated by the individual doctor as a demonstrator, or

even entertainer, who produced observable therapeu-

tic effects, and became the interpreter of mechanical-

ly-produced scientific images that could then be used

to generate a diagnosis.

Much of the appeal of the x-ray in the years after

WWI lay in its mechanical sophistication. X-ray techno-

logy became a mass industry as companies in the U.S.and

Germany marketed their high-quality equipment domes-

tically and abroad.Radiology epitomized mass production,

with its “investment in apparatus and its striving to rou-

tinize labour” and its call for “elaborate plants, machinery

and other equipment, and consequently for heavy invest-

ment.”42

Radiology and the x-ray industry, along with the

hospital, increasingly fit into paradigms of big business

undergirded with the appeal of advanced technology.

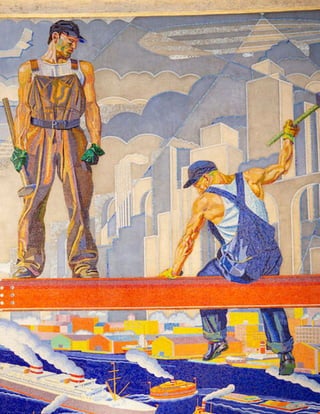

The conception of the x-ray as a sophisticated ma-

chine, and the radiologist as a sophisticated machine

technician, accorded well with the emerging view of the

body as a machine.The machine metaphor was prevalent

in the work of Fritz Kahn, a German physician who was

known for his widely-circulated popular science books

and illustrations. He published an image entitled Der

Mensch als Industriepalast, or Man as Industrial Pa-

lace, that depicted the human body as a modern chemi-

cal plant. In the image, the interior of the human body

consists of a network of parts that correspond to func-

tions. Unlike the metaphor of the body as an economy,

which understood the body as an interconnected whole

26

TECHNOLOGY AND PARADIGM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yhrspring2021-211020115003/85/YHR-Spring-2021-31-320.jpg)

![coordinated by immaterial forces, the factory metaphor

proposed a functional relationship between parts of the

body and the body as a whole. Whereas the ‘economy’

of the body was regulated by the flow of material-im-

material substance between undifferentiated parts, the

body as ‘machine’integrated the specific functions of the

parts into a system optimized for efficiency. The body,

like the modern hospital, was conceived along the lines

of a factory, where labor was divided so as to maximize

the production of power.

Other captions for Fritz Kahn’s illustrations in-

clude “Comparison of force transmission in a car and

the outer ear”and “the basic forms and functions of the

bones and joints in man’s body are very similar to our

own architectural and technological constructions.”43

Kahn’s graphics portray the modern preoccupation

with the body as an energy system designed for maxi-

mum efficiency.44

The body was a machine engineered for efficiency,

but, like the x-ray machine, it required the expertise of

trained technicians to maintain it. This expertise existed

not in the space between the patient’s and the doctor’s bo-

dies, as it had in the first years of x-ray treatment. Rather,

expert medical opinion was produced in reference to an

increasingly large body of knowledge that was generated

between hospitals and research facilities and between va-

rious departments within the hospital. In the context of

the proliferation of scientifically-backed research studies

and the dispersal of care between multiple departments

and practitioners, health evaluations were increasingly

produced in reference to stable bodies of knowledge that

existed outside of the doctor’s experience and judgment.

The patient’s own symptoms and accounts of illness played

a smaller role in orienting diagnosis and treatment.Rather,

medical evaluation was increasingly conducted through

measurement and statistics. Blood tests, urinalysis, and

other diagnostic tests became more prevalent,as did stan-

dardized written forms that allowed practitioners to easily

extract and compare patient information.45

By the 1940s, the Eastman Kodak Company ad-

vertised its radiographic equipment by its ability to “pro-

vide inside information.” A pamphlet circulated by the

43 National Library of Medicine, History of Medicine Division, National Institutes of Health, “Dream Anatomy”

online gallery.

44 Anson Rabinbach, The Human Motor: Energy, Fatigue, and the Origins of Modernity (Berkeley, CA: University

of California Press, 1992).

45 Howell, Technology in the Hospital.

company proclaimed that radiography “in modern in-

dustry” was useful for its ability to procure “a wealth of

Fritz Kahn's illustration entitled Der Mensch als

Industriepalast, or Man as Industrial Palace, depicting

the human body as a modern chemical plant. [3]

VOLUME XI ISSUE I SPRING 2021

27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yhrspring2021-211020115003/85/YHR-Spring-2021-32-320.jpg)

![VER THE COURSE of approximately

fifty years from its invention, the x-ray

was progressively fashioned into a medi-

cal technology that fit the particular aims

of institutional biomedicine in the United States. The

technology has continued to exist as an authoritative

method of representing and knowing the body.In orga-

nizing diagnoses around the structures discernable be-

neath the surface of heterogeneous human experience,

the x-ray helps to maintain boundaries between health

and illness. But the x-ray was not adapted to fit cir-

cumscribed notions of health and disease; it helped to

produce a particular form of diagnosis at the same time

that the epistemic landscape of American medicine

was evolving. Debuting onto a field of divergent medi-

cal sects and little to no professional organization, the

x-ray in its early years was understood in the context

of ambiguously efficacious experimental modalities. In

this context, it was considered a potential therapy along

the lines of other electrical devices that would soon

go out of fashion. Its diagnostic capacity was selected

as the space of American medicine was narrowing to

sanction scientific medicine as the only allowable me-

dical paradigm.

The x-ray’s eventual institutionalized use privile-

ged certain ways of knowing the body at the expense

of others. It enabled genuinely new representations of

the healthy body and of the pathologies that threate-

ned it, allowing for new sites of intervention and cura-

tive techniques. However, it simultaneously narrowed

the field of interpretations of illness that could count

as legitimate. The x-ray enforced a paradigm in which

treatment and diagnosis were framed in relation to the

disease, rather than to the patient. By the 1920s, cer-

tain medical professionals had identified the tenden-

cy for the specialist’s understanding of particularities

to cut against medicine’s goal of promoting health for

the whole person. Ernst Phillip Boas, a prominent phy-

sician, medical director, and author, noted that young

51 Robert Charles Yamashita, "Intervention before disease: Asymptomatic biomedical screening," (PhD diss., Uni-

versity of California, Berkeley, 1992), 66.

52 Yamashita, “Intervention before disease," 66.

practitioners who were trained in particular disorders

did not know how to assess subtle indications in a per-

son’s constitution that were associated with systemic di-

sease. He noted that “they could treat diseases but not

the sick,” and that “the reality of medical practice [is]

the opposite: ‘We treat the sick not diseases.’”51

The x-ray was implicit in circulating the notion of

an individual’s health as the proper functioning of in-

dividual parts.This notion enabled philosophies of care

that prioritized technical intervention into particular

body parts and systems. But adequate treatment often

called not for “fixing that specific part,” but for “retur-

ning the whole to a sense of normality.”52

Electrical the-

rapies in the nineteenth century were justified by their

ability to act on bodies that were understood to exist in

the same ontological category; the same vital substance

flowed through both the device and the body in which

it produced effects. Homeopathic practices interpreted

their cures along the same lines; substances in the world

were liable to induce effects on the body due to their

being of the same kind as the treated ailment.Although

the x-ray eventually distanced itself from these theories

that were deemed unscientific, it internalized many of

the same assumptions about causation in the body.The

x-ray, conceived as a machine with interrelated functio-

nal parts that together produced energy in an efficient

way, was understood to act on bodies that were consti-

tuted in precisely the same manner.

The x-ray’s effects often could not be explained

on the terms that it helped to enforce as legitimate. Al-

though the machine was taken to embody the success-

ful integration of science and industry into American

medicine, its authority was conceptualized in the very

paradigms that it had rejected as characteristic of an

esoteric or non-modern way of practicing medicine. In

casting light on affinities between orthodox and unor-

thodox medical paradigms, the x-ray shows how legiti-

mation is negotiated through explanations and uses for

particular technologies at particular times. If the x-ray

is one thread in the passing over from heterodox thera-

peutic practices to the institutionalization of scientific

technologies of care, it reveals important contradictions

within the ascension of biomedicine.

CONCLUSION:

INTERIORITY

O

VOLUME XI ISSUE I SPRING 2021

29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/yhrspring2021-211020115003/85/YHR-Spring-2021-34-320.jpg)

![American X-Ray Journal 1, no.1 (1899).

The American X-Ray Journal 1, no. 2 (1899).

D. J. Rivieré, “Annals of Physico-Therapy,” Physi-

co-Therapeutic Institute of Paris, April 1903.

Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Pub-

lic Health Service, National Institutes of Health,

“200 Years of American Medicine (1776-1976)”

an exhibit at the National Library of Medicine.

Dr. E. J. Fraser, “Medical Electricity: a Treatise on the

Nature of Vital Electricity in Health and Disease,

With plain Instructions in the uses of Artificial

Electricity as a curative agent,” Chicago, 1863.

Electricity Consumption: The New Treatment Of

Phthisis By The Use ... Contributed to The Times

Los Angeles Times (1886-1922); Sep 5, 1897;

ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Los Angeles

Times, pg. 16

“Electro-Therapeutics,” Chicago Daily Tribune (1872-

1922); Jul 23, 1899; ProQuest Historical News-