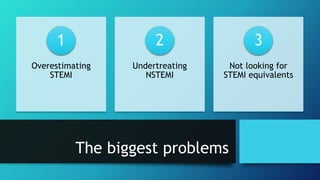

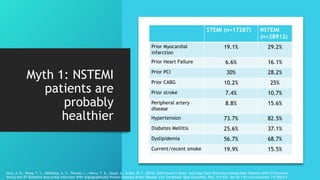

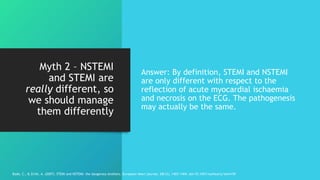

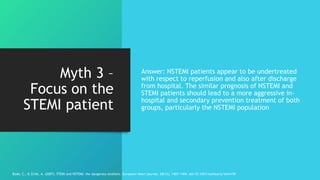

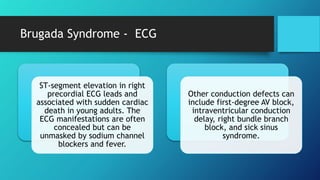

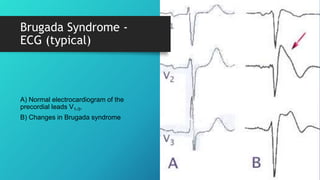

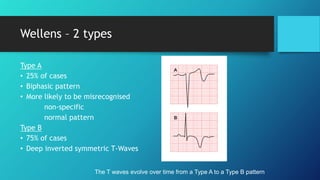

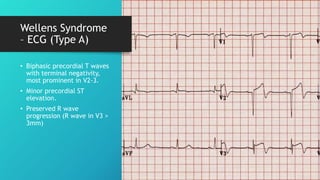

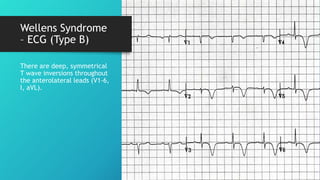

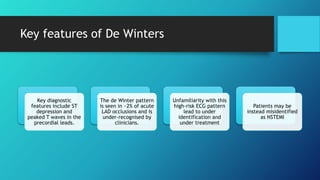

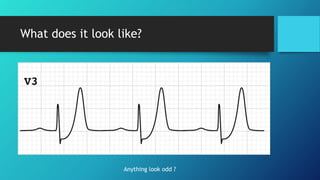

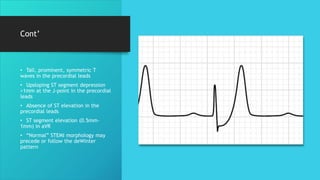

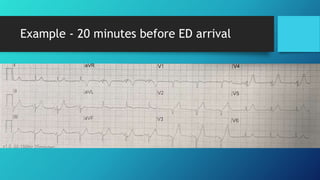

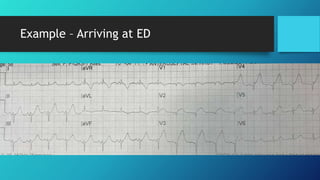

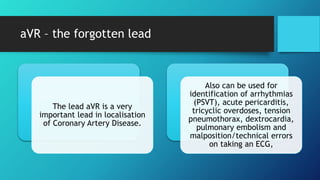

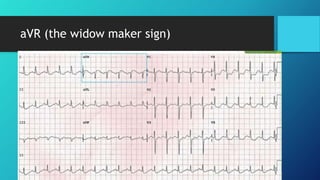

The document critiques the current paradigm of acute myocardial infarction (MI) management, arguing that the distinction between STEMI and NSTEMI is flawed and hinders advancements in reperfusion therapy. It highlights the risks of misdiagnosis and undertreatment for NSTEMI patients and outlines common ECG patterns that can be mistaken for myocardial infarction. The authors call for a reevaluation of educational approaches in cardiology to address these issues and improve patient outcomes.