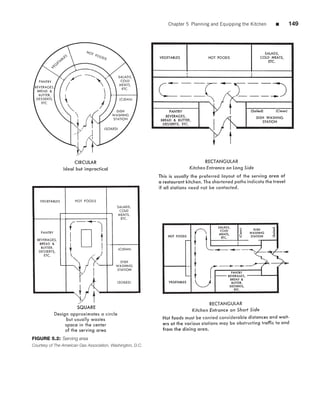

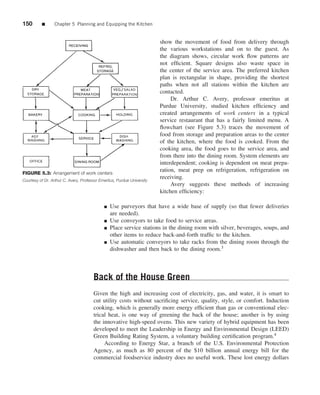

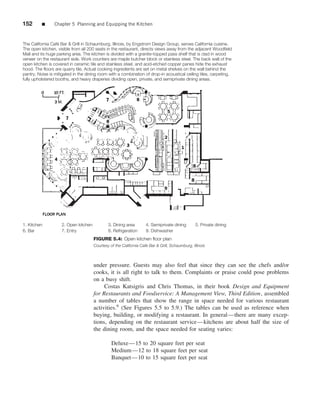

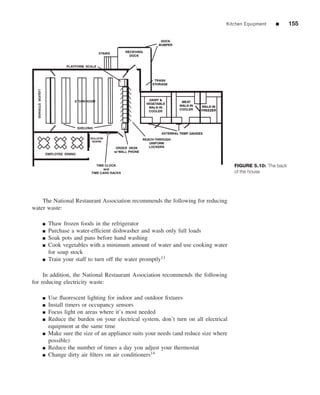

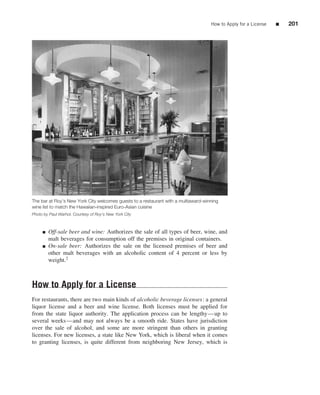

The sixth edition of 'The Restaurant: From Concept to Operation' by John R. Walker serves as a comprehensive guide to restaurant management, covering topics from restaurant concepts to operations and legal matters. This edition includes updated chapters on sustainability, leadership, and the history of dining, alongside practical insights and pedagogical features for both students and instructors. It is designed to aid those entering the restaurant industry, providing tools and knowledge for success in a competitive environment.