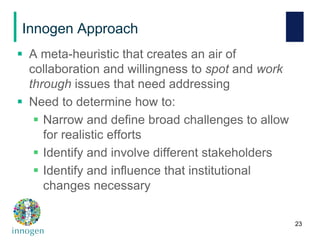

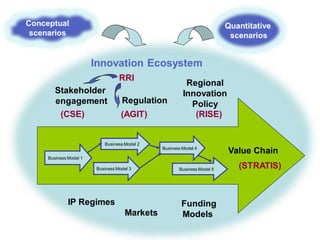

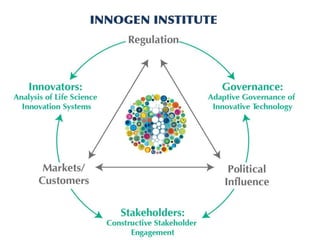

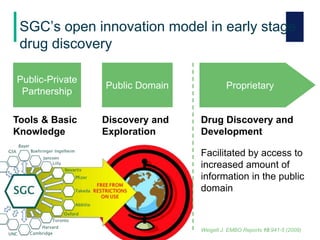

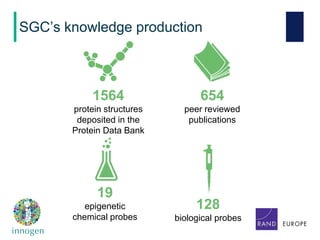

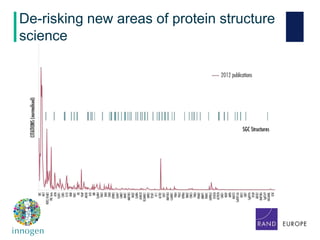

The document discusses the role and impact of public-private partnerships in health innovation, particularly highlighting the Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC) as a successful model for open-access research in drug discovery. It emphasizes the need for interdisciplinary collaboration, long-term governance, and addressing social and political barriers to innovation. Additionally, it suggests further research into the advantages of open-access versus intellectual property-based models in different contexts.

![However there are disincentives to

investment

Unprotected intellectual property

(private sector)

Limited opportunities for spillover

effects (public sector)

‘The SGC needs to show evidence of

wider benefits in the form of economic

benefits, spillovers and encouraging

investment. The science is good but the

SGC hasn’t catalysed the development of

a cluster in the way [we] hoped.’](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scienceandinnovationslides2014-140707094101-phpapp01/85/Science-Innovation-2014-Foresighting-Trajectories-for-Advanced-Innnovative-Technologies-15-320.jpg)