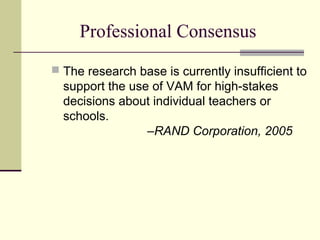

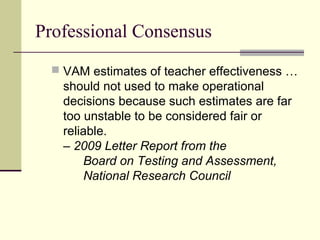

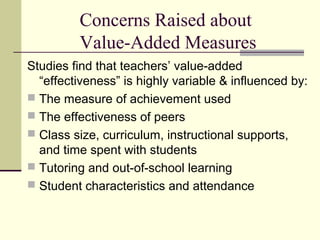

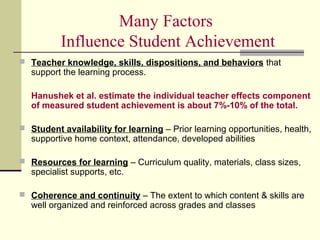

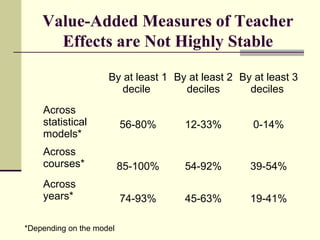

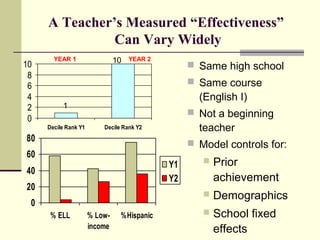

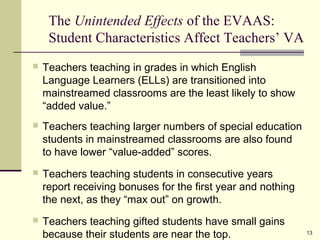

This document discusses developing and assessing teacher effectiveness. It notes that while value-added models (VAMs) are being promoted as tools for teacher evaluation, research shows that VAM estimates of teacher effectiveness are unstable and influenced by many factors outside a teacher's control. The document then outlines 10 recommendations for developing a comprehensive system for evaluating and supporting teacher effectiveness, including using standards-based evaluations, performance assessments, multiple measures of teaching practice and student outcomes, professional development, and addressing other influences on teaching.

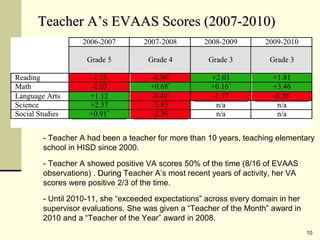

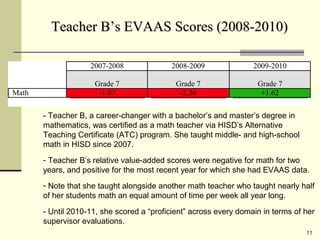

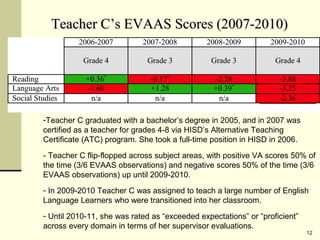

![The Unintended Effects of VA Teacher

Evaluation in Houston: Three Cases in Point

In spring of 2011, a number of HISD

teachers’ contracts were not renewed, largely

due to:

“a significant lack of student progress attributable

to the educator,” and

“insufficient student academic growth reflected by

[EVAAS] value-added scores.”

These teachers filed wrongful termination

appeals.

Let’s take a look at the EVAAS data for 3 of

them 9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/developingandassessingteachereffectiveness-top101-120813112805-phpapp02/85/Developing-and-Assessing-Teacher-Effectiveness-9-320.jpg)

![UNINTENDED EFFECTS

“The most pernicious effect of these [test-

based accountability] systems is to cause

teachers to resent the children who don’t

score well.”

—Anonymous teacher,

in a workshop many years ago](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/developingandassessingteachereffectiveness-top101-120813112805-phpapp02/85/Developing-and-Assessing-Teacher-Effectiveness-14-320.jpg)

![Teacher Educators Learn

This [scoring] experience…has forced me to

revisit the question of what really matters in

the assessment of teachers, which – in turn –

means revisiting the question of what really

matters in the preparation of teachers.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/developingandassessingteachereffectiveness-top101-120813112805-phpapp02/85/Developing-and-Assessing-Teacher-Effectiveness-27-320.jpg)

![Cooperating Teachers

Reflect on Practice

[The scoring process] forces you to be clear

about “good teaching;” what it looks like,

sounds like. It enables you to look at your

own practice critically/with new eyes.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/developingandassessingteachereffectiveness-top101-120813112805-phpapp02/85/Developing-and-Assessing-Teacher-Effectiveness-28-320.jpg)