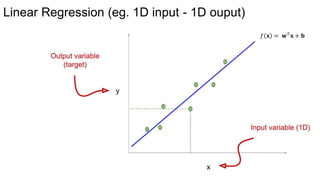

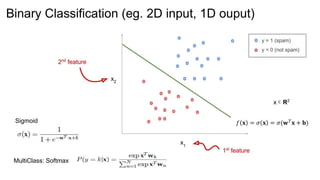

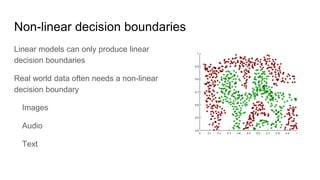

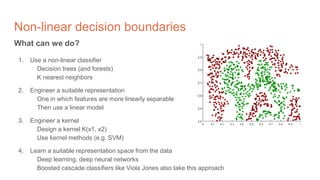

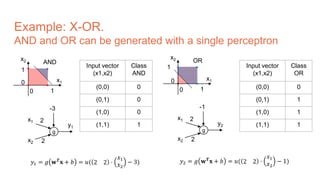

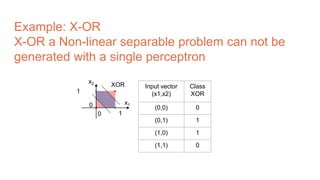

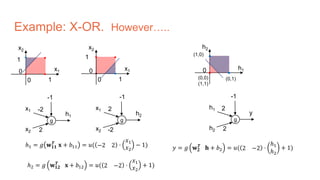

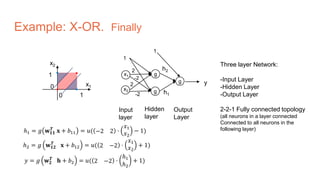

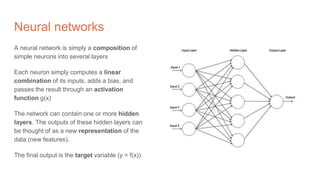

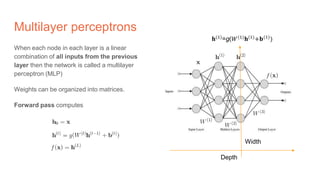

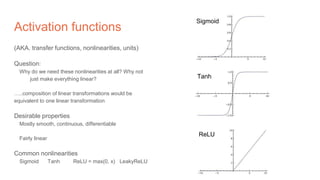

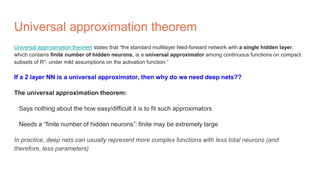

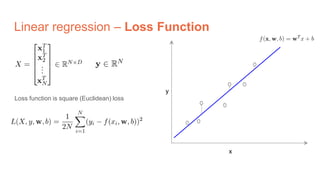

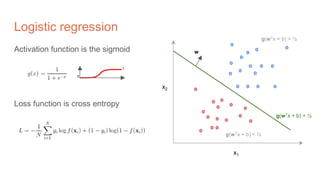

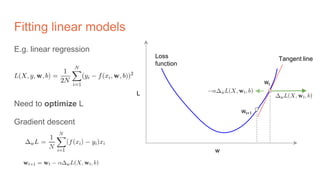

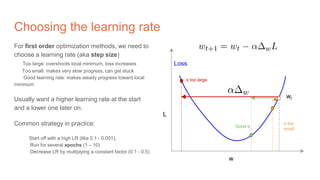

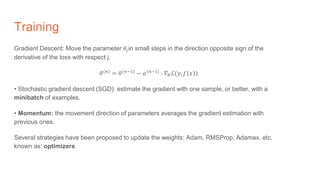

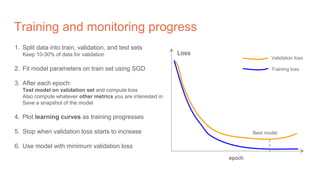

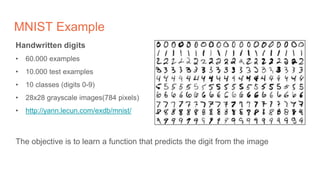

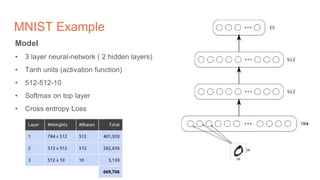

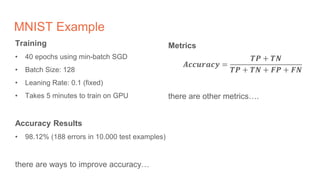

The document discusses the concepts of multilayer perceptrons and neural networks, contrasting linear and non-linear models to address real-world data that often requires non-linear decision boundaries. It explains the structure of neural networks, emphasizing the importance of activation functions and the universal approximation theorem, which asserts that multilayer networks can approximate continuous functions. Additionally, it covers training techniques such as gradient descent, validation, and accuracy metrics, highlighting the training of neural networks using specific datasets like MNIST.

![[course site]

Day 2 Lecture 1

Multilayer Perceptron

Elisa Sayrol](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dlai2017d2l1multilayerperceptron-170926130833/75/Multilayer-Perceptron-DLAI-D1L2-2017-UPC-Deep-Learning-for-Artificial-Intelligence-1-2048.jpg)